Wind Energy Plan for Dukes County

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Outer Cape Cod and Nantucket Sound

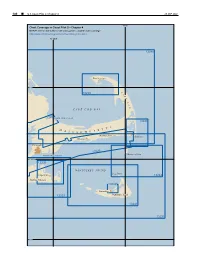

186 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 2, Chapter 4 26 SEP 2021 70°W Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 2—Chapter 4 NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml 70°30'W 13246 Provincetown 42°N C 13249 A P E C O D CAPE COD BAY 13229 CAPE COD CANAL 13248 T S M E T A S S A C H U S Harwich Port Chatham Hyannis Falmouth 13229 Monomoy Point VINEYARD SOUND 41°30'N 13238 NANTUCKET SOUND Great Point Edgartown 13244 Martha’s Vineyard 13242 Nantucket 13233 Nantucket Island 13241 13237 41°N 26 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 2, Chapter 4 ¢ 187 Outer Cape Cod and Nantucket Sound (1) This chapter describes the outer shore of Cape Cod rapidly, the strength of flood or ebb occurring about 2 and Nantucket Sound including Nantucket Island and the hours later off Nauset Beach Light than off Chatham southern and eastern shores of Martha’s Vineyard. Also Light. described are Nantucket Harbor, Edgartown Harbor and (11) the other numerous fishing and yachting centers along the North Atlantic right whales southern shore of Cape Cod bordering Nantucket Sound. (12) Federally designated critical habitat for the (2) endangered North Atlantic right whale lies within Cape COLREGS Demarcation Lines Cod Bay (See 50 CFR 226.101 and 226.203, chapter 2, (3) The lines established for this part of the coast are for habitat boundary). It is illegal to approach closer than described in 33 CFR 80.135 and 80.145, chapter 2. -

Inventory of Habitat Modifications to Sandy Beaches ME-NY Rice 2015

Inventory of Habitat Modifications to Sandy Beaches in the U.S. Atlantic Coast Breeding Range of the Piping Plover (Charadrius melodus) prior to Hurricane Sandy: Maine to the North Shore and Peconic Estuary of New York1 Tracy Monegan Rice Terwilliger Consulting, Inc. June 2015 Recovery Task 1.2 of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) Recovery Plan for the piping plover (Charadrius melodus) prioritizes the maintenance of “natural coastal formation processes that perpetuate high quality breeding habitat,” specifically discouraging the “construction of structures or other developments that will destroy or degrade plover habitat” (Task 1.21), “interference with natural processes of inlet formation, migration, and closure” (Task 1.22), and “beach stabilization projects including snowfencing and planting of vegetation at current or potential plover breeding sites” (Task 1.23) (USFWS 1996, pp. 65-67). This assessment fills a data need to identify such habitat modifications that have altered natural coastal processes and the resulting abundance, distribution, and condition of currently existing habitat in the breeding range. Four previous studies provided these data for the United States (U.S.) continental migration and overwintering range of the piping plover (Rice 2012a, 2012b) and the southern portion of the U.S. Atlantic Coast breeding range (Rice 2014, 2015a). This assessment provides these data for one habitat type – namely sandy beaches within the northern portion of the breeding range along the Atlantic coast of the U.S. prior to Hurricane Sandy. A separate report assessed tidal inlet habitat in the same geographic range prior to Hurricane Sandy (Rice 2015b). Separate reports will assess the status of these two habitats in the northern and southern portions of the U.S. -

1000 Great Places

1000 Great Places Last update 7/20/2010 Name Town Ames Nowell State Park Abington The Discovery Museum Acton The Long Plain Museum Acushnet Mount Greylock State Reservation Adams Saint Stanislaus Kostka Church Adams Susan B. Anthony Birthplace Museum Adams The Quaker Meeting House Adams Veterans Memorial Tower Adams Robinson State Park Agawam Six Flags New England Agawam Knox Trail Alford John Greenleaf Whittier House Amesbury Lowell’s Boat Shop Amesbury Powwow River Amesbury Rocky Hill Meetinghouse Amesbury Emily Dickinson Museum Amherst Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art Amherst Jones Library Amherst National Yiddish Book Center Amherst Robert Frost Trail Amherst Addison Gallery of American Art Andover The Andover Historical Society Andover Aquinnah Gay Head Cliffs Aquinnah Cyrus Dallin Art Museum Arlington Mystic Lakes Arlington Robbins Farm Park Arlington Robbins Library Arlington Spy Pond Arlington Wilson Statue in Arlington Center Arlington Mount Watatic Ashburnham Trap Falls in Willard Brook State Forest Ashby Ashfield Plain Historic District Ashfield Double Edge Theatre Ashfield Ashland State Park Ashland Town Forest Ashland Profile Rock Assonet Alan E. Rich Environmental Park Athol Athol Historical Society Athol Capron Park Zoo Attleboro National Shrine of Our Lady of La Salette Attleboro Oak Knoll Wildlife Sanctuary Attleboro Goddard Rocket launching site @ Goddard Park Auburn DW Field Park Avon Nashua River Rail Trail Ayer Cahoon Museum of American Art Barnstable Hyannis Harbor Barnstable JFK Museum Barnstable Long Pasture -

Minerals Management Service Documentation of Section 106 Finding of Adverse Effect (Revised)

Minerals Management Service Documentation of Section 106 Finding of Adverse Effect (Revised) Prepared for Submission to Massachusetts Historical Commission Pursuant to 36 CFR 800.6(a)(3) for the Cape Wind Energy Project This report was prepared for the Minerals Management Service (MMS) under contract No. M08-PC-20040 by Ecosystem Management & Associates, Inc. (EM&A). Brandi M. Carrier Jones (EM&A) compiled and edited the report with information provided by the MMS and with contributions from Public Archaeology Laboratory, Inc. (PAL), National Park Service Determination of Eligibility, as well as by composing original text. Minerals Management Service Documentation of Section 106 Finding of Adverse Effect (Revised) Prepared for Submission to Massachusetts Historical Commission Pursuant to 36 CFR 800.6(a)(3) for the Cape Wind Energy Project Brandi M. Carrier Jones, Compiler and Editor Ecosystem Management & Associates, Inc. REPORT AVAILABILITY Copies of this report can be obtained from the Minerals Management Service at the following addresses: U.S. Department of the Interior Minerals Management Service 381 Elden Street Herndon VA, 20170 http://www.mms.gov/offshore/AlternativeEnergy/CapeWind.htm CITATION Suggested Citation: MMS (Minerals Management Service). 2010. Documentation of Section 106 Finding of Adverse Effect for the Cape Wind Energy Project (Revised). Prepared by B. M. Carrier Jones, editor, Ecosystem Management & Associates, Inc. Lusby, Maryland. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction........................................................................................................................ -

Bookletchart™ Martha's Vineyard

BookletChart™ Martha’s Vineyard – Eastern Part NOAA Chart 13238 A reduced-scale NOAA nautical chart for small boaters When possible, use the full-size NOAA chart for navigation. Included Area Published by the ebbs south-southwestward. Wasque Shoal extends southward of Wasque Point, the southeastern National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration extremity of Chappaquiddick Island. The shoal, which dries about 2 miles National Ocean Service south of Wasque Point, rises abruptly from deep Muskeget Channel. Office of Coast Survey Martha’s Vineyard and Chappaquiddick Island have a combined length of 18 miles; the two islands are separated by Edgartown Harbor, Katama www.NauticalCharts.NOAA.gov Bay, and the narrow slough connecting them. The northern extremity of 888-990-NOAA Martha’s Vineyard is about 3 miles southeastward of the western end of Cape Cod. Martha’s Vineyard is well settled, especially along its northern What are Nautical Charts? shore, and is popular as a summer resort. Along the northern shore the island presents a generally rugged appearance. The southern shore is Nautical charts are a fundamental tool of marine navigation. They show low and fringed with ponds, none of which has navigable outlets to the water depths, obstructions, buoys, other aids to navigation, and much sea. Approaching from the south, the principal landmarks are a more. The information is shown in a way that promotes safe and standpipe at Edgartown, an aerolight near the center of the island, a efficient navigation. Chart carriage is mandatory on the commercial church spire near Chilmark in the western part, a tall radar tower north ships that carry America’s commerce. -

The Lure of Cape

The Lure of Cape Cod It's difficult to define what it is about Cape Cod that In parks all over the has continued to draw so many of us back to Cape and Islands, experience it again and again each summer. local residents Perhaps it's the irresistible combination of its assemble in unique natural beauty - miles of beautiful, white- gazebos in their sand beaches and dunes and lush, fascinating band uniforms and Chatham Band Concert marshes teeming with wildlife - its charming history present a mix of dating back to the 17th century, and its abundance music sure to delight all and get feet tapping. While of family-oriented activities, and beautiful Cape Cod parents and grandparents relax on blankets or in vacation rentals. If lying on a gorgeous beach or folding chairs waiting for the music to begin, reading a book on a porch overlooking wetlands children run around the bandstand and play in the isn't enough for you, we suggest you take area set aside for dancing. Then, when the band advantage of some of these wonderful, in most strikes up, the dancing begins – couples, parents cases free, quintessentially-Cape experiences: with their children and even solo folks enjoy swaying to the music. Adding to the Normal Town Band Concerts Rockwell-like experience at some concerts are strings of balloons rising into the summer skies. Small town band concerts are a part of Americana. Although these concerts are disappearing in many At most of these events, you can bring food and areas of the country, they remain a treasured and non-alcoholic beverages to enjoy and make it an delightful part of the summer experience on Cape even more festive event. -

409 Part 110—Anchorage Regulations

Coast Guard, DHS Pt. 110 § 109.07 Anchorages under Ports and time being as Captain of the Port. Waterways Safety Act. When the vessel is at a port where The provisions of section 4 (a) and (b) there is no Coast Guard officer, pro- of the Ports and Waterways Safety Act ceedings will be initiated in the name as delegated to the Commandant of the of the District Commander. U.S. Coast Guard in Pub. L. 107–296, 116 [CGFR 67–46, 32 FR 17727, Dec. 12, 1967, as Stat. 2135, authorize the Commandant amended by USCG–2007–27887, 72 FR 45903, to specify times of movement within Aug. 16, 2007] ports and harbors, restrict vessel oper- ations in hazardous areas and under § 109.20 Publication; notice of pro- hazardous conditions, and direct the posed rule making. anchoring of vessels. The sections list- (a) Section 4 of the Administrative ed in § 110.1a of this subchapter are reg- Procedure Act (5 U.S.C. 553), requires ulated under the Ports and Waterways publication of general notice of pro- Safety Act. posed rule making in the FEDERAL [CGD 3–81–1A, 47 FR 4063, Jan. 28, 1982, as REGISTER (unless all persons subject amended by USCG–2003–14505, 68 FR 9535, thereto are named and either person- Feb. 28, 2003] ally served or otherwise have actual notice thereof in accordance with law), § 109.10 Special anchorage areas. except to the extent that there is in- An Act of Congress of April 22, 1940, volved (1) any military, naval, or for- provides for the designation of special eign affairs function of the United anchorage areas wherein vessels not States or (2) any matter relating to more than sixty-five feet in length, agency management or personnel or to when at anchor, will not be required to public property, loans, grants, benefits, carry or exhibit anchorage lights. -

Martha's Vineyard Lighthouses Part 1

151 Lagoon Pond Road Vineyard Haven, MA 02568 Formerly MVMUSEUM The Dukes County Intelligencer NOVEMBER 2019 VOLUME 60 Quarterly NO. 4 Martha’s Vineyard Museum’s Journal of Island History MVMUSEUM.ORG Martha’s Vineyard Lighthouses Martha’s Vineyard Part 1 Lighthouses, Part 1 Before electrification and automation, lighthouses were surrounded by storage sheds, oil houses, outhouses, and other small buildings, as shown in this photograph taken at Gay Head in the late 1890s. Gay Head West Chop Holmes Hole MVMUSEUM.ORG MVMUSEUM Cover, Vol. 60 No. 4.indd 1 3/20/20 11:02:55 AM MVM Membership Categories Details at mvmuseum.org/membership Basic ..............................................$55 Partner ........................................$150 Sustainer .....................................$250 Patron ..........................................$500 Benefactor................................$1,000 Basic membership includes one adult; higher levels include two adults. All levels include children through age 18. Full-time Island residents are eligible for discounted membership rates. Contact Sydney Torrence at 508-627-4441 x117. Reviving a Tradition Early in its history, when it was still named the Dukes County Intelli- gencer, this journal occasionally devoted an entire issue to a single subject. The first examples were relatively brief: Lloyd C. M. Hare on Vineyard whaling captains in San Francisco (February 1960), Sidney N. Riggs on Vineyard meeting houses (August 1960), and Alice Forbes Howland on the Pasque Island Fishing Club (February 1962) all topped out at twenty pages. Over time, however, they began to grow. Joseph Elvin’s article on the history of trap fishing, which took up the entirety of the May 1964 is- sue, was thirty-five pages, and Allan Keith’s on the mammals of Martha’s Vineyard (November 1969) was fifty-two. -

Lighthouses of Massachusetts TR State MASSACHUSETTS

Form No. 10-306 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE r NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES r INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS __________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS INAME HISTORIC Lighthouses of Massachusetts - Thematic Group Nomination AND/OR COMMON same LOCATION STREET ft NUMBER m|]1 tf ple Iocat1ons ( See i ndi V i dual f OHUS ) NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT various ICINITYOF STATE CODE Massachusetts ; , d?gE seT^ction 10 HCLASSIFICATION v CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT —PUBLIC , ;j " XLOCCUPIED . .-- •*'"""' _ AGRICULTURE. -X.MUSEUM _ BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE . K-UNOGCOPIED —COMMERCIAL JCPARK —STRUCTURE -XBOTH . r -CfWQRK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL -XPRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT fl /.SIN PROCESS ' AYES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT _ SCIENTIFIC ^thematic —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION group —NO —MILITARY XOTHER: 3?.ti VG 1 i qh -f-hrouse AGENCY REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: (if applicable) United states Coast Guard - First Coast Guard District STREET & NUMBER 408 Atlantic Avenue CITY. TOWN STATE Boston n/a VICINITY OF Massachusetts LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC, various STREETS NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE 1 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic Assets of the Commonwealth (also, see continuation sheet) DATE 1980 -FEDERAL JL.STATE COUNTY LOCAL -

Fishermen of the Atlantic

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine History of Maine Fisheries Special Collections 1920 Fishermen of the Atlantic Fishing Masters' Association Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/fisheries Part of the Agricultural and Resource Economics Commons, and the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons Repository Citation Fishing Masters' Association, "Fishermen of the Atlantic" (1920). History of Maine Fisheries. 144. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/fisheries/144 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in History of Maine Fisheries by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOSTON yy. - m Fairbanks-Morse Type "C-0" INSURANCE Marine Oil Engine COMPANY Incorporated 1873 Established by Service Capital, $1,000,000 Surplus, $2,000,000 -- i I INSURANCE ON FISHING I L VESSELS AND OUTFITS A SPECIALTY FIRE, MARINE, WAR, YACHT, AUTOMOBILE and TOURISTS' BAGGAGE INSURANCE XRi& HOME OFFICE, 87 KILBY STREET FAIRBANKS, MORSE & CO. 1 BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS BOSTON NEW YORK BALTIMORE New York Office, 66 Beaver Street New York ADMINISTRATION BUILDING, BOSTON FISH PIER, BOSTON, MASS. JOHN NAGLE. President R. J. AHEARN, Treasurer JOHN NAGLE, JR., Vice-president GEORGE I,. POLAND, Secretary JOHN NAGLE CO., I~C. Fishing Masters' Wholesale and Commission Dealers in all kinds of Association Fresh Fish of the Our Specialty is supplying Fresh and Frozen Bait of All Kinds to Fishermen Administration Building Atlantic Boston Fish Pier, Boston, Mass. Telephones, Port Hill 5650 and 5651 ,\ .Il.\h'ITATA OF IKFOIChl;\TTO?\', TSSUED ANNTTL\T,LY, COI\"l'A\IN IS(: THE ONLY Coi3IJT~I4Yl"l'< LIST OF FISHING VESSELS OF I1OSTON, (;L0TT('ESl1lClt, 1'I:O\'IN('lCTO\VN, CHATH.\.\I, XliCIV l~l~~l)FOI~l),l'OItTTAL\KI), AfIiC. -

THE DUKES COUNTY INTELLIGENCER INDEX for the YEARS 1959 THROUGH NOVEMBER 2003 Prepared by Ruth Galvin, Helen Gelotte and Tweed Roosevelt

THE DUKES COUNTY INTELLIGENCER INDEX FOR THE YEARS 1959 THROUGH NOVEMBER 2003 Prepared by Ruth Galvin, Helen Gelotte and Tweed Roosevelt Arranged alphabetically in this Index, which includes every issue published through November 2003, are titles of articles, authors of articles, subjects (when not obvious from the title) and descriptions of photographs and drawings that are not part of an indexed article in which one would expect to find them. Copies of all issues, including those that are out of print, are available at the Gale Huntington Library of History of the Martha's Vineyard Historical Society or by mail. Martha's Vineyard Historical Society, Box 1310, Edgartown, MA 02539. Telephone 508.627.4441 ISSUE DATE PAGE INDEX ITEM Abel's Hill Cemetery, Chilmark, Photo August, 2002 64 "Absolutely Very Last Word [re] Martha of the Vineyard" February, 1988 116 Accidents, Care of Injured Seamen August, 1977 3 Actors, MV August, 1966 3 Acushnet , Herman Melville Whaling Ship November, 1979 47 Adams Family of Martha's Vineyard, Book Review February, 1988 133 Adams, Lily's Post Office, North Tisbury, Photo August, 1966 14 Adams, Lucy Palmer, Biography August, 1979 15 Adams, Lucy Palmer, Two Letters by August, 1979 44 Adams, President John February, 1982 91 Adams, Rev. John, Photo November, 1980 55 Adams, Rev. John May, 1985 139 Adams, Rev. John, Preaching on Martha's Vineyard February, 1991 121 Adams, Sarah Butler, Biography August, 1979 15 Addlington, Francis, (Zadoc Norton) Slanderer February, 1990 147 "Adventure on St. Augustine Island" May, -

Inventory of Habitat Modifications to Sandy Oceanfront Beaches in the U.S

INVENTORY OF HABITAT MODIFICATIONS TO SANDY OCEANFRONT BEACHES IN THE U.S. ATLANTIC COAST BREEDING RANGE OF THE PIPING PLOVER (CHARADRIUS MELODUS) AS OF 2015: MAINE TO NORTH CAROLINA January 2017 revised March 2017 Prepared for the North Atlantic Landscape Conservation Cooperative and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service by Terwilliger Consulting, Inc. Tracy Monegan Rice [email protected] Recommended citation: Rice, T.M. 2017. Inventory of Habitat Modifications to Sandy Oceanfront Beaches in the U.S. Atlantic Coast Breeding Range of the Piping Plover (Charadrius melodus) as of 2015: Maine to North Carolina. Report submitted to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Hadley, Massachusetts. 295 p. 1 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................... 4 METHODS ............................................................................................................................................... 5 Development ......................................................................................................................................... 6 Public and NGO Beachfront Ownership ............................................................................................... 9 Beachfront Armor ............................................................................................................................... 10 Sediment Placement ...........................................................................................................................