RANSOMING POLICIES and PRACTICES in the WESTERN and CENTRAL BILAD AL-SUDAN Cl800-1910

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'White Slavery': Trafficking, the Jewish Association, and the Dangerous

DOI: 10.14197/atr.20121777 Looking Beyond ‘White Slavery’: Trafficking, the Jewish Association, and the dangerous politics of migration control in England, 1890-1910 Rachael Attwood Abstract This article seeks to revise Jo Doezema‘s suggestion that ‗the white slave‘ was the only dominant representation of ‗the trafficked woman‘ used by early anti-trafficking advocates in Europe and the United States, and that discourses based on this figure of injured innocence are the only historical discourses that are able to shine light on contemporary anti-trafficking rhetoric. ‗The trafficked woman‘ was a figure painted using many shades of grey in the past, with a number of injurious consequences, not only for trafficked persons but also for female labour migrants and migrant populations at large. In England, dominant organisational portrayals of ‗the trafficked woman‘ had acquired these shades by the 1890s, when trafficking started to proliferate amid mass migration from Continental Europe, and when controversy began to mount over the migration of various groups of working-class foreigners to the country. This article demonstrates these points by exploring the way in which the Jewish Association for the Protection of Girls and Women (JAPGW), one of the pillars of England‘s early anti-trafficking movement, represented the female Jewish migrants it deemed at risk of being trafficked into sex work between 1890 and 1910. It argues that the JAPGW stigmatised these women, placing most of the blame for trafficking upon them and positioning them to a greater or a lesser extent as ‗undesirable and undeserving working-class foreigners‘ who could never become respectable English women. -

Mali 2018 International Religious Freedom Report

MALI 2018 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The constitution prohibits religious discrimination and grants individuals freedom of religion in conformity with the law. The law criminalizes abuses against religious freedom. On January 31, the government adopted a new national Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) strategy that included interfaith efforts and promotion of religious tolerance. The Ministry of Religious Affairs and Worship was responsible for administering the national CVE strategy, in addition to promoting religious tolerance and coordinating national religious activities such as pilgrimages and religious holidays for followers of all religions. Terrorist groups used violence and launched attacks against civilians, security forces, peacekeepers, and others they reportedly perceived as not adhering to their interpretation of Islam. In the center of the country, affiliates of Jamaat Nasr al- Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) attacked multiple towns in Mopti Region, threatening Christian, Muslim, and traditional religious communities, reportedly for heresy. Muslim religious leaders condemned extremist interpretations of sharia, and non- Muslim religious leaders condemned religious extremism. Some Christian missionaries expressed concern about the increased influence in remote areas of organizations they characterized as violent and extremist. Religious leaders, including Muslims and Catholics, jointly called for peace among all faiths at a celebration marking Eid al-Fitr in June hosted by President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita. In January Muslim, Protestant, and Catholic religious leaders called for peace and solidary among faiths at a conference organized by the youth of the Protestant community. The president of the High Islamic Council of Mali (HCI) and other notable religious leaders announced the necessity for all religious leaders to work toward national unity and social cohesion. -

“More Valuable Than Any Other Commodity: Arabic Manuscript Libraries and Their Role in Islamic Revival of the Bilad’S-Sudan”

SANKORE' Institute of Islamic - African Studies International “More Valuable Than Any Other Commodity: Arabic Manuscript Libraries and Their Role in Islamic Revival of the Bilad’s-Sudan” Muhammad Shareef SANKORE' Institute of Islamic - African Studies www.sankore.org/www.siiasi.org ﺑِ ﺴْ ﻢِ اﻟﻠﱠﻪِ ا ﻟ ﺮﱠ ﺣْ ﻤَ ﻦِ ا ﻟ ﺮّ ﺣِ ﻴ ﻢِ وَﺻَﻠّﻰ اﻟﻠّﻪُ ﻋَﻠَﻲ ﺳَﻴﱢﺪِﻧَﺎ ﻣُ ﺤَ ﻤﱠ ﺪٍ وﻋَﻠَﻰ ﺁ ﻟِ ﻪِ وَ ﺻَ ﺤْ ﺒِ ﻪِ وَ ﺳَ ﻠﱠ ﻢَ ﺗَ ﺴْ ﻠِ ﻴ ﻤ ﺎً “More Valuable Than Any Other Commodity: Arabic Manuscript Libraries and Their Role in Islamic Revival of the Bilad’s- Sudan” Al-Hassan ibn Muhammad al-Wazaan az-Ziyaati (Leo Africanus) described the value that 15th century African Muslims placed upon books and literacy when he said: "وﻳﺒﺎع هﻨﺎ اﻟﻜﺜﻴﺮ ﻣﻦ اﻟﻜﺘﺐ اﻟﻤﺨﻄﻮﻃﺔ اﻟﺘﻲ ﺗﺄﺗﻲ ﻣﻦ ﺑﻼد اﻟﺒﺮﺑﺮ، وﻳﺠﻨﻰ ﻣﻦ هﺬا اﻟﺒﻴﻊ رﺑﺢ ﻳﻔﻮق آ ﻞّ ﺑﻘﻴﺔ اﻟﺴﻠﻊ" “Here many manuscript books are sold which come from the lands of the Berber. This trade fetches profits that outrival those of all other commodities.”1 The high value that African Muslims have given to Arabic and ajami books is attributed to their high regard for learning and erudition. This is especially true with regard to religious and spiritual matters. It was for this reason that traders were attracted to these lands with the most rare Arabic books that reflected diverse opinions and wide authorship from all over the Muslim world. Because of this enthusiasm for erudition, there emerged in the bilad’s-sudan the highly honored vocation of paper manufacturing following in the footsteps of the literary communities of North Africa2. -

Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria: the Role of Traditional Institutions

Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria Past, Present, and Future Edited by Abdalla Uba Adamu ii Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria Past, Present, and Future Proceedings of the National Conference on Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria. Organized by the Kano State Emirate Council to commemorate the 40th anniversary of His Royal Highness, the Emir of Kano, Alhaji Ado Bayero, CFR, LLD, as the Emir of Kano (October 1963-October 2003) H.R.H. Alhaji (Dr.) Ado Bayero, CFR, LLD 40th Anniversary (1383-1424 A.H., 1963-2003) Allah Ya Kara Jan Zamanin Sarki, Amin. iii Copyright Pages © ISBN © All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the editors. iv Contents A Brief Biography of the Emir of Kano..............................................................vi Editorial Note........................................................................................................i Preface...................................................................................................................i Opening Lead Papers Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria: The Role of Traditional Institutions...........1 Lt. General Aliyu Mohammed (rtd), GCON Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria: A Case Study of Sarkin Kano Alhaji Ado Bayero and the Kano Emirate Council...............................................................14 Dr. Ibrahim Tahir, M.A. (Cantab) PhD (Cantab) -

Policies for Sustainable Mobility and Accessibility in Cities of Mali

Page 1 Policies for sustainable mobility and accessibility in cities of Mali Page 2 ¾ SSATP – Mali - Policies for Sustainable Mobility and Accessibility in Urban Areas – October 2019 Page 3 ¾ SSATP – Mali - Policies for Sustainable Mobility and Accessibility in Urban Areas – October 2019 Policies for sustainable mobility and accessibility in urban areas of Mali An international partnership supported by: Page 4 ¾ SSATP – Mali - Policies for Sustainable Mobility and Accessibility in Urban Areas – October 2019 The SSATP is an international partnership to facilitate policy development and related capacity building in the transport sector in Africa. Sound policies lead to safe, reliable, and cost-effective transport, freeing people to lift themselves out of poverty and helping countries to compete internationally. * * * * * * * The SSATP is a partnership of 42 African countries: Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, Djibouti, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Gabon, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, South Sudan, Tanzania, Togo, Tunisia, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe; 8 Regional Economic Communities (RECs); 2 African institutions: African Union Commission (AUC) and United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA); Financing partners for the Third Development Plan: European Commission (main donor), -

A Reinterpretation of Islamic Foundation of Jihadist Movements in West Africa

EAS Journal of Humanities and Cultural Studies Abbreviated Key Title: EAS J Humanit Cult Stud ISSN: 2663-0958 (Print) & ISSN: 2663-6743 (Online) Published By East African Scholars Publisher, Kenya Volume-2 | Issue-1 | Jan-2020 | DOI: 10.36349/easjhcs.2020.v02i01.001 Research Article A Reinterpretation of Islamic Foundation of Jihadist Movements in West Africa Dr. Usman Abubakar Daniya*1 & Dr. Umar Muhammad Jabbi2 1,2Department of History, Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto, Nigeria Abstract: It is no exaggeration that the Jihads of the 19th century West Africa were Article History phenomenal and their study varied. Plenty have been written about their origin, development Received: 04.12.2019 and the decline of the states they established. But few scholars have delved into the actual Accepted: 11.12.2019 settings that surrounded their emergence. And while many see them as a result of the Published: 15.01.2020 beginning of Islamic revivalism few opined that they are the continuation of it. This paper Journal homepage: first highlights the state of Islam in the region; the role of both the scholars, students and th https://www.easpublisher.com/easjhcs rulers from the 14 century, in its development and subsequently its spread among the people of the region as impetus to the massive awareness and propagation of the faith that Quick Response Code was to led to the actions and reactions that subsequently led to the revolutions. The paper, contrary to many assertions, believes that it was actually the growth of Islamic learning and scholarship and not its decline that led to the emergence and successes of the Jihad movements in the upper and Middle Niger region area. -

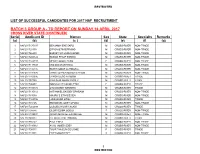

Batch 3 Group A

RESTRICTED LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES FOR 2017 NAF RECRUITMENT BATCH 3 GROUP A - TO REPORT ON SUNDAY 16 APRIL 2017 CROSS RIVER STATE (CONTINUED) Serial Applicant ID Names Sex State Specialty Remarks (a) (b) (c ) (d) (e) (f) (g) 1 NAF2017175197 BENJAMIN ENE EKPO M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 2 NAF201728378 EFFIOM ETIM EFFIONG M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 3 NAF201746430 BASSEY SYLVANUS OKON M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 4 NAF2017200122 EDIKAN PHILIP ESSIEN M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 5 NAF2017148737 MERCY OKON EKPO F CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 6 NAF2017117347 ENE EDEM ANTIGHA M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 7 NAF2017186435 EDWIN IOBAR ACHIBONG M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 8 NAF2017191076 CHRISTOPHER MOSES EFFIOM M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 9 NAF2017166695 UKPONG ESO AKABOM M CROSS-RIVER TRADE 10 NAF201767788 PAULINUS OKON BASSEY M CROSS-RIVER TRADE 11 NAF201796402 IMMACULATA OKON ETIM F CROSS-RIVER TRADE 12 NAF2017100172 OTU BASSEY KENNETH M CROSS-RIVER TRADE 13 NAF2017135112 NATHANIEL BASSEY EPHRAIM M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 14 NAF201733038 MAURICE ETIM ESSIEN M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 15 NAF2017169796 LUKE OGAR OTAH M CROSS-RIVER TRADE 16 NAF201745165 EMMANUEL ODEY OFUNA M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 17 NAF2017202699 OGBUDU HILARY AGABI M CROSS-RIVER TRADE 18 NAF201798686 GLORY ELIMA ODIDO F CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 19 NAF2017199991 ADADA MICHAEL EKANNAZE M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 20 NAF201749812 CLEMENT ADIE BISONG M CROSS-RIVER TRADE 21 NAF201786142 PAUL ENEJI . M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 22 NAF2017180661 ACHU JAMES ODEY M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 23 NAF201706031 TOURITHA EUNICE USHIE F CROSS-RIVER -

Annuaire Statistique 2015 Du Secteur Développement Rural

MINISTERE DE L’AGRICULTURE REPUBLIQUE DU MALI ----------------- Un Peuple - Un But – Une Foi SECRETARIAT GENERAL ----------------- ----------------- CELLULE DE PLANIFICATION ET DE STATISTIQUE / SECTEUR DEVELOPPEMENT RURAL Annuaire Statistique 2015 du Secteur Développement Rural Juin 2016 1 LISTE DES TABLEAUX Tableau 1 : Répartition de la population par région selon le genre en 2015 ............................................................ 10 Tableau 2 : Population agricole par région selon le genre en 2015 ........................................................................ 10 Tableau 3 : Répartition de la Population agricole selon la situation de résidence par région en 2015 .............. 10 Tableau 4 : Répartition de la population agricole par tranche d'âge et par sexe en 2015 ................................. 11 Tableau 5 : Répartition de la population agricole par tranche d'âge et par Région en 2015 ...................................... 11 Tableau 6 : Population agricole par tranche d'âge et selon la situation de résidence en 2015 ............. 12 Tableau 7 : Pluviométrie décadaire enregistrée par station et par mois en 2015 ..................................................... 15 Tableau 8 : Pluviométrie décadaire enregistrée par station et par mois en 2015 (suite) ................................... 16 Tableau 9 : Pluviométrie enregistrée par mois 2015 ........................................................................................ 17 Tableau 10 : Pluviométrie enregistrée par station en 2015 et sa comparaison à -

Les Esclaves Du Commandant Quiquandon

NOTES ET DOCUMENTS Michal Tymowski Les esclaves du commandant Quiquandon Dans la section Outre-mer des Archives nationales françaises, préservées autrefois à Paris et aujourd’hui à Aix-en-Provence, un document, dans la correspondance générale des gouverneurs du Soudan français, nous semble intéressant1. Il s’agit d’une dépêche du gouverneur Albert Grodet, adressée le 10 janvier 1895 au ministre des Colonies, décrivant les infractions du commandant Quiquandon, l’un des conquérants du Soudan occidental. Après s’être entretenu avec Goussou Traore, serviteur de Quiquandon, qui confirma que le commandant possédait des esclaves dans la localité de Kou- likoro, ce gouverneur donna l’ordre au commandant de la région de Bamako d’envoyer un interprète escorté de spahis afin que celui-ci libérât les esclaves mentionnés. Treize filles, quatre jeunes hommes et six femmes furent amenés à Bamako, et, plus tard vingt-huit autres personnes suivirent. Goussou Traore déclarait qu’il y en avait plus et estimait au nombre de trente, les filles et les garçons travaillant la terre pour le compte de Quiquan- don. Ensuite une jeune femme, Aminata Sidibe, et sa mère, habitant toutes deux la maison dans le domaine de Koulikoro, firent des dépositions devant les autorités françaises certifiant que toutes les personnes acheminées à Bamako étaient des esclaves du commandant et provenaient, soit de la prise de la localité de Kinian, soit de dons qui étaient ensuite transmis à cet officier par les deux souverains successifs du Kénédougou, Tieba et Babemba. Le gouverneur Grodet, en constatant qu’aucun citoyen français n’avait le droit de posséder des esclaves, libéra toutes ces personnes. -

Rapport De L'etude Genre Menee Dans Les Aires De

RAPPORT DE L’ETUDE GENRE MENEE DANS LES AIRES DE SANTE APPUYEE PAR MEDECINS DU MONDE ESPAGNE DANS LE DISTRICT SANITAIRE DE BAFOULABE Draft Projet d’Amélioration de l’Accès aux Soins de Santé Primaires et l’Exercice des Droits Sexuels et Reproductifs, Région de Kayes au Mali-Cercle de Bafoulabe Bamako, 21 octobre 2017 - Moussa TRAORE, consultant principal - Dr Sékou Koné, assistant de recherche - Adiaratou Diakité, socio-anthropologue - Salimata Sissoko, assistante de recherche Projet d’Amélioration de l’Accès aux Soins de Santé Primaire et l’Exercice des Droits Sexuels et Reproductifs, Région de Kayes, Cercle de Bafoulabe Sommaire PAGES LISTE DES TABLEAUX ............................................................................................................................... 3 Sigles et Abréviations .............................................................................................................................. 4 REMERCIEMENTS .................................................................................................................................... 7 I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 8 II. CONTEXTE ET JUSTIFICATIONS ............................................................................................ 9 III. APERÇUE SOCIODEMOGRAPHIQUE ET SANITAIRE ................................................. 10 IV. OBJECTIFS DE L’ETUDE .................................................................................................... -

Bartolomé De Las Casas, Soldiers of Fortune, And

HONOR AND CARITAS: BARTOLOMÉ DE LAS CASAS, SOLDIERS OF FORTUNE, AND THE CONQUEST OF THE AMERICAS Dissertation Submitted To The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Damian Matthew Costello UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio August 2013 HONOR AND CARITAS: BARTOLOMÉ DE LAS CASAS, SOLDIERS OF FORTUNE, AND THE CONQUEST OF THE AMERICAS Name: Costello, Damian Matthew APPROVED BY: ____________________________ Dr. William L. Portier, Ph.D. Committee Chair ____________________________ Dr. Sandra Yocum, Ph.D. Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Kelly S. Johnson, Ph.D. Committee Member ____________________________ Dr. Anthony B. Smith, Ph.D. Committee Member _____________________________ Dr. Roberto S. Goizueta, Ph.D. Committee Member ii ABSTRACT HONOR AND CARITAS: BARTOLOMÉ DE LAS CASAS, SOLDIERS OF FORTUNE, AND THE CONQUEST OF THE AMERICAS Name: Costello, Damian Matthew University of Dayton Advisor: Dr. William L. Portier This dissertation - a postcolonial re-examination of Bartolomé de las Casas, the 16th century Spanish priest often called “The Protector of the Indians” - is a conversation between three primary components: a biography of Las Casas, an interdisciplinary history of the conquest of the Americas and early Latin America, and an analysis of the Spanish debate over the morality of Spanish colonialism. The work adds two new theses to the scholarship of Las Casas: a reassessment of the process of Spanish expansion and the nature of Las Casas’s opposition to it. The first thesis challenges the dominant paradigm of 16th century Spanish colonialism, which tends to explain conquest as the result of perceived religious and racial difference; that is, Spanish conquistadors turned to military force as a means of imposing Spanish civilization and Christianity on heathen Indians. -

In Changing Nigerian Society: a Discussion from the Perspective of Ibn Khaldun’S Concept Ofñumran

THE CONTRIBUTION OF UTHMAN BIN FODUYE (D.1817) IN CHANGING NIGERIAN SOCIETY: A DISCUSSION FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF IBN KHALDUN’S CONCEPT OFÑUMRAN SHUAIBU UMAR GOKARUMalaya of ACADEMY OF ISLAMIC STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA KUALA LUMPUR University 2017 THE CONTRIBUTION OF UTHMAN BIN FODUYE (D.1817) IN CHANGING NIGERIAN SOCIETY: A DISCUSSION FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF IBN KHALDUN’S CONCEPT OF ÑUMRAN SHUAIBU UMAR GOKARU Malaya THESIS SUBMITTED IN FULFILMENTof OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UniversityACADEMY OF ISLAMIC STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA KUALA LUMPUR 2017 UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA ORIGINAL LITERARY WORK DECLARATION Name of Candidate: Shuaibu Umar Gokaru Matric No: IHA140056 Name of Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Title of Project Paper/Research Report/Dissertation/Thesis (“this Work”) THE CONTRIBUTION OF UTHMAN BIN FODUYE (D. 1817) IN CHANGING NIGERIAN SOCIETY: A DISCUSSION FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF IBN KHALDUN’S CONCEPT OF ÑUMRAN Field of Study: Islamic Civilisation (Religion) I do solemnly and sincerely declare that: (1) I am the sole author/author of this Work; (2) This Work is original; (3) Any use of any work in which copyright exists was done by way of fair dealing and for permitted purposes and any excerpt or extract from, or reference to or reproduction of any copyrightMalaya work has been disclosed expressly and sufficiently and the title of the Work and its authorship have been acknowledged in this Work; (4) I do not have any actual knowledge nor do I ought reasonably to know that the making of this work