Personal Notes Page 1 Learning from the Spelling of < Love > Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The English Language

The English Language Version 5.0 Eala ðu lareow, tæce me sum ðing. [Aelfric, Grammar] Prof. Dr. Russell Block University of Applied Sciences - München Department 13 – General Studies Winter Semester 2008 © 2008 by Russell Block Um eine gute Note in der Klausur zu erzielen genügt es nicht, dieses Skript zu lesen. Sie müssen auch die “Show” sehen! Dieses Skript ist der Entwurf eines Buches: The English Language – A Guide for Inquisitive Students. Nur der Stoff, der in der Vorlesung behandelt wird, ist prüfungsrelevant. Unit 1: Language as a system ................................................8 1 Introduction ...................................... ...................8 2 A simple example of structure ..................... ......................8 Unit 2: The English sound system ...........................................10 3 Introduction..................................... ...................10 4 Standard dialects ................................ ....................10 5 The major differences between German and English . ......................10 5.1 The consonants ................................. ..............10 5.2 Overview of the English consonants . ..................10 5.3 Tense vs. lax .................................. ...............11 5.4 The final devoicing rule ....................... .................12 5.5 The “th”-sounds ................................ ..............12 5.6 The “sh”-sound .................................. ............. 12 5.7 The voiced sounds / Z/ and / dZ / ...................................12 5.8 The -

Reading Foundational Skills

Common Core State StandardS for engliSh language artS & literaCy in hiStory/SoCial StudieS, SCienCe, and teChniCal SubjeCtS reading Foundational skills The following supplements the Reading Standards: Foundational Skills (K–5) in the main document (pp. 14–16). See page 40 in the bibliography of this appendix for sources used in helping construct the foundational skills and the material below. Phoneme-Grapheme correspondences Consonants Common graphemes (spellings) are listed in the following table for each of the consonant sounds. Note that the term grapheme refers to a letter or letter combination that corresponds to one speech sound. Figure 8: Consonant Phoneme-Grapheme Correspondences in English Common Graphemes (Spellings) Phoneme Word Examples for the Phoneme* /p/ pit, spider, stop p /b/ bit, brat, bubble b /m/ mitt, comb, hymn m, mb, mn /t/ tickle, mitt, sipped t, tt, ed /d/ die, loved d, ed /n/ nice, knight, gnat n, kn, gn /k/ cup, kite, duck, chorus, folk, quiet k, c, ck, ch, lk, q /g/ girl, Pittsburgh g, gh /ng/ sing, bank ng, n /f/ fluff, sphere, tough, calf f, ff, gh, ph, lf /v/ van, dove v, ve /s/ sit, pass, science, psychic s, ss, sc, ps /z/ zoo, jazz, nose, as, xylophone z, zz, se, s, x /th/ thin, breath, ether th /th/ this, breathe, either th /sh/ shoe, mission, sure, charade, precious, notion, mission, sh, ss, s, ch, sc, ti, si, ci special /zh/ measure, azure s, z /ch/ cheap, future, etch ch, tch /j/ judge, wage j, dge, ge /l/ lamb, call, single l, ll, le /r/ reach, wrap, her, fur, stir r, wr, er/ur/ir /y/ you, use, feud, onion y, (u, eu), i /w/ witch, queen w, (q)u /wh/ where wh /h/ house, whole h, wh *Graphemes in the word list are among the most common spellings, but the list does not include all possible graph- emes for a given consonant. -

LL P Silent E Recognition.Pdf

® LEVEL 7 | Phonics Lexia Lessons Silent E Recognition Description This lesson is designed to teach students the phonics rule that when a Silent e occurs after a single consonant at the end of a syllable, it usually makes the first vowel “say its name” (long sound), as in the word time. These kinds of syllables are called Silent e syllables. Knowledge of the Silent e syllable type helps students apply word-attack strategies for reading and spelling. TEACHER TIPS This lesson contrasts the Silent e syllable type (long vowel sound) with the closed syllable type (short vowel sound). When you pronounce the words, stretch out the medial vowel sound, whether it is short or long, so that students have more time to hear it. Sounds to stretch out will be shown in the lesson as repeated letters—such as maaad for mad and maaade for made. For the letters a, e, i, and o, the long sound of the letter is also its name. Because long u can be pronounced /yoo/ or /oo/, it is presented later in this lesson. PREPARATION/MATERIALS • Copies of the word cards from the end of the lesson • Keyword Image Cards (provided in the Core5 Resources Hub on the Support for Primary Standard: CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RF.1.3c - Know final -e and common vowel - Know Standard: CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RF.1.3c Primary team conventions for representing long vowel sounds. RF.1.3b Supporting Standards: RF.1.2a, Instruction page.) Warm-up Use a phonemic awareness activity to review short and long vowel sounds. -

Why Do You Spell That?

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by IPU Institutional Repository Why Do You Spell That? ― A Brief History of the Evolution of English Orthography ― なぜこのように綴るのか ─ 英語正字法進展の略歴 ― 次世代教育学部国際教育学科 ファラーンティー・ダニエル FERRANTE, Daniel Department of International Education Faculty of Education for Future Generations 要旨:綴りは英語を学ぶ上で最も難しいものの一つである。ネイティブスピーカーさえ手を焼くほど であるため,間違いを防ぐためにしばしばスペルチェックや自動修正など現代的なツールに頼る。 こ のような難解な正字法に関して,「なぜ英語の綴りはそれほど複雑なものになったのか」とよく問わ れる。本稿では,英語の綴りに見られる明白な矛盾と不明瞭な英語正字法に与えた大きな影響につい て統合的に考察する。 Abstract:Spelling is one of the most challenging aspects of learning English. Even native speakers have difficulty with it and often rely on modern tools such as spell check and autocorrect to minimize mistakes. With such a challenging orthography, people often ask how it is that English spelling became so complex. This paper is synthesis of some of the more apparent discrepancies in English spelling and some of the larger influences on its less than transparent orthography. Keywords:English Orthography, Spelling, Dictionary, Printing Press, The Great Vowel Shift I have nothing but contempt for anyone who can spell the world has a spelling bee. Other countries do host a word only one way. English language spelling bees. And some countries host similar competitions involving vocabulary and - Mark Twain (apocryphal) grammar. Some noteworthy examples: 1.0Introduction French: Perhaps the closest thing to a spelling bee in another language is Quebec’s Dictée des Unlike most other languages, English spelling and Amériques. This competition, which started in 1994, pronunciation is so difficult and complex that even challenges participants in both spelling and grammar. native language speakers struggle with it. This goes Would-be participants must first pass a locally held beyond confusion with homophones such as then / grammar test before progressing on to further than, to, too, and two, or their, they’re, and there. -

Difference Between Pronunciation and Spelling

Acquiring and teaching pronunciation (part 1) Neal Snape • Language conveys meanings from one person to another through – spoken sounds • They can tell the difference in pronunciation – written letters between ‘drain’ and ‘train’. – gestures • At the suprasegmental (higher) level they know the • Speakers know how to pronounce: difference between – the words – ‘Fine’, ‘Fine?’ and ‘Fine!’:- the intonation patterns change – sentences as the voice rises and falls. – Utterances of their native language. Difference between pronunciation and spelling 1 First cause The Great Vowel Shift First cause: the Great Vowel Shift Second cause: letterpress printing Third cause: the northern cities vowel shift + predictable difficulty Examples –the Great Vowel Shift- Second cause Letterpress Printing Before the After the Great Vowel Great Vowel • Johannes Gutenberg invented (1450) Shift Shift • Spellings were settled • name [na:m] → [neım] • feel [fɛ:l][fe:l] → [f i:l] • time [ti:m] → [taım] • home [hɔ:m] → [hoʊm] • now [nu:] → [naʊ] Third cause Northern cities vowel shift Letterpress printing was invented = spellings were settled 1400s 1450 1700s ------------------------------------------------------ The Great vowel shift =sounds continued to change 2 Acquiring and teaching a new writing system • The big division in the writing systems of the world is • The Chinese character- based system of writing links between those based on meaning and those based a written sign to a meaning; the character 人 means on sounds, as seen in Figure 5.1. a person, the sign 象 an elephant; it is not necessary to know how人 is pronounced or even to know what the Chinese spoken word actually is in order to read it. • A Chinese-English dictionary does not tell you the spoken form: 口 is simply given as ‘mouth’. -

Phonics TRB Coding Chart

Coding Charts The following coding charts briefly explain vowel and spelling rules, syllable-division patterns, letter clusters, and coding marks used in Saxon’s phonics programs. Basic Coding TO CODE USE EXAMPLE Accented syllables Accent marks noÆ C ’s that make a /k/ sound, as in “cat” K-backs |cat C ’s that make a /s/ sound, as in “cell” Cedillas çell Combinations; diphthongs Arcs ar™ Digraphs; trigraphs; quadrigraphs Underlines SH___ Final, stable syllables Brackets [fle Long vowel sounds Macrons nO Schwa vowel sounds (rhymes with vowel sound in “sun,” as Schwas o÷ (or ) in “some,” “about,” and “won”) Short vowel sounds Breves log Sight words Circles ≤are≥ Silent letters Slash marks mak´ Affixes Boxes work ingfl Syllables Syllable division lines cac\tus Voiced sounds Voice lines hiß Vowel Rules RULE CODING EXAMPLE A vowel followed by a consonant is short; code it logcatsit with a breve. An open, accented vowel is long; code it with a nOÆ mEÆ íÆ gOÆ macron. AÆ\|cor™n OÆ\p»n EÆ\v»n A vowel followed by a consonant and a silent e is long; code the vowel with a macron and cross out the nAm´ hOp´ lIk´ silent e. An open, unaccented vowel can make a schwa b«\nanÆ\« E\rAs´Æ hO\telÆ sound. The letters e, o, and u can also make a long sound. The letter i can also make a short sound. JU\lŒÆ di\vId´Æ Copyright by Saxon Publishers, Inc. Spelling Rules† RULE EXAMPLE Floss Rule: When a one-syllable root word has a short vowel sound followed by the sound /f/, /l/, or /s/, it is puff doll pass usually spelled ff, ll, or ss. -

Practice-Syllable-Types.Pdf

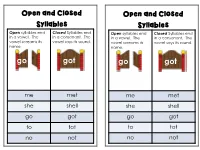

Open and Closed Open and Closed Syllables Syllables Open syllables end Closed Syllables end Open syllables end Closed Syllables end in a vowel. The in a consonant. The in a vowel. The in a consonant. The vowel screams its vowel says its sound. vowel screams its vowel says its sound. name. name. go got go got me met me met she shell she shell go got go got to tot to tot no not no not Open and Closed Open and Closed Syllables Syllables Open syllables end Closed Syllables end Open syllables end Closed Syllables end in a vowel. The in a consonant. The in a vowel. The in a consonant. The vowel screams its vowel says its sound. vowel screams its vowel says its sound. name. name. go got go got Open and Closed Open and Closed Syllables Syllables Open syllables end Closed Syllables end Open syllables end Closed Syllables end in a vowel. The in a consonant. The in a vowel. The in a consonant. The vowel screams its vowel says its sound. vowel screams its vowel says its sound. name. name. go got go got me met me met she shell she shell go got go got to tot to tot no not no not we web we web hi hid hi hid be bet be bet Open, Closed and Open, Closed and silent-e Syllables silent-e Syllables Open Closed Silent e Open Closed Silent e syllables end Syllables end syllables syllables end Syllables end syllables in a vowel. in a have a VCe in a vowel. -

Orthographies in Early Modern Europe

Orthographies in Early Modern Europe Orthographies in Early Modern Europe Edited by Susan Baddeley Anja Voeste De Gruyter Mouton An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org ISBN 978-3-11-021808-4 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-021809-1 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-021806-2 ISSN 0179-0986 e-ISSN 0179-3256 ThisISBN work 978-3-11-021808-4 is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 License, ase-ISBN of February (PDF) 978-3-11-021809-1 23, 2017. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-021806-2 LibraryISSN 0179-0986 of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ae-ISSN CIP catalog 0179-3256 record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. ISBN 978-3-11-028812-4 e-ISBNBibliografische 978-3-11-028817-9 Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliogra- fie;This detaillierte work is licensed bibliografische under the DatenCreative sind Commons im Internet Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs über 3.0 License, Libraryhttp://dnb.dnb.deas of February of Congress 23, 2017.abrufbar. -

PL2 Production of English Word-Final Consonants: the Role of Orthography and Learner Profile Variables

L2 Production of English word-final consonants... PL2 PRODUCTION OF ENGLISH WORD-FINAL CONSONANTS: THE ROLE OF ORTHOGRAPHY AND LEARNER PROFILE VARIABLES PRODUÇÃO DE CONSOANTES FINAIS DO INGLÊS COMO L2: O PAPEL DA ORTOGRAFIA E DE VARIÁVEIS RELACIONADAS AO PERFIL DO APRENDIZ Rosane Silveira* ABSTRACT The present study investigates some factors affecting the acquisition of second language (L2) phonology by learners with considerable exposure to the target language in an L2 context. More specifically, the purpose of the study is two-fold: (a) to investigate the extent to which participants resort to phonological processes resulting from the transfer of L1 sound-spelling correspondence into the L2 when pronouncing English word-final consonants; and (b) to examine the relationship between rate of transfer and learner profile factors, namely proficiency level, length of residence in the L2 country, age of arrival in the L2 country, education, chronological age, use of English with native speakers, attendance in EFL courses, and formal education. The investigation involved 31 Brazilian speakers living in the United States with diverse profiles. Data were collected using a questionnaire to elicit the participants’ profiles, a sentence-reading test (pronunciation measure), and an oral picture-description test (L2 proficiency measure). The results indicate that even in an L2 context, the transfer of L1 sound-spelling correspondence to the production of L2 word-final consonants is frequent. The findings also reveal that extensive exposure to rich L2 input leads to the development of proficiency and improves production of L2 word-final consonants. Keywords: L2 consonant production; grapho-phonological transfer; learner profile. RESUMO O presente estudo examina fatores que afetam a produção de consoantes em segunda língua (L2) por aprendizes que foram consideravelmente expostos à língua-alvo em um contexto de L2. -

Why Is English Spelling So Wierd Weird?

Why Is English Spelling So Wierd Weird? James Harbeck English is a Caesar’s body It has had a lot of… input… from many different sources. Old English Hwæt? † Old English † ò Hwæt! We Gardena in geardagum, þeodcyninga, þrym gefrunon, hu ða æþelingas ellen fremedon. ò (Yo! We spear-Danes in yore-days have heard fame of folk-kings, how those noblemen did great deeds.) Time and tide Old English: 625~1066 Middle English: 1066~1476 Early Modern English: 1476~1776 Modern English: 1776~last week † Time and tide † ò Letters we stopped using: þ, ð, æ, ƿ, ȝ ò Sounds we stopped making: ò /y, Y, x, ɣ, ç/ spelled y, h, g, ȝ ò true length distinctions in vowels and double consonants ò Onset sound combinations we stopped using: hl, hr, hn, cn, gn, wr ò Inflectional endings that got worn off: nearly all of them, with mostly just some e and s and es left † Time and tide † ò Sounds we added: ò f/v distinction ò s/z distinction ò n/ŋ distinction ò “zh” ò Letters we added: ò q ò z ò i/j distinction ò v/u distinction ò w for ƿ French 1066 and all that † French † ò Large percentage of modern English vocabulary ò Large percentage of modern English vocabulary ò Much from Norman French ò Brought scribes with them ò But the words didn’t all come at the same time – we have more recent borrowings as well ò How French the word looks depends on how recently we “borrowed” it † French † ò Less changed: ò ballet, corps, macaque, cigarette, rendezvous, chateau, petit, etiquette, avant-garde ò More changed: ò peasant, money, leaven, castle, petty, ticket, vanguard † French -

Skill: 2-Syllable Silent E Instructional Day: One

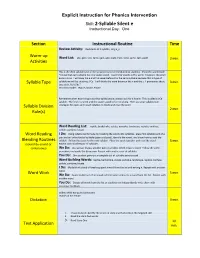

Explicit Instruction for Phonics Intervention Skill: 2-Syllable Silent e Instructional Day: One Section Instructional Routine Time Review Activity: Flashcards of 1 syllable, long a_e Warm-up Word List: ate, gate, late, tame, gale, sale, mate, hate, lame, same, tale, wade 2 min. Activities This is the third syllable type of the six patterns to be introduced to students. Show the word inside. “I know that each syllable has one vowel sound. I see three vowels in this word. However, the word ends in an e. I will keep the e and the vowel before it in the same syllable because that is type of Syllable Type syllable we will be studying: VCe. I will divide the word between the n and the s. I pronounce these 3 min. two parts /in/ /sīd/.” Words to model: reptile, locate, estate Remember when examining a word for syllabication; always look for a final e. This is called a VCe syllable. The final e is silent and the vowel sound before it is long. Then use your syllabication Syllable Division strategies for open and closed syllables to divide and read the word. 2 min. Rule(s) Word Reading List: reptile, backstroke, estate, pancake, landscape, replete, confuse, collide, combine, locate Word Reading I Do: Using syllable cards made by breaking the words into syllables, place first syllable card of a pair and tell what kind of syllable (open or closed), identify the vowel, and show how to read the Blending Routines syllable. Follow the steps for the next syllable. Place the cards together and read the word. -

Spelling and Phonetic Inconsistencies in English: a Problem for Learners of English As a Foreign/Second Language Nneka Umera-Okeke

Spelling and Phonetic Inconsistencies in English: A Problem for Learners of English as a Foreign/Second Language Nneka Umera-Okeke Abstract: Spelling is simply the putting together of a number of letters of the alphabet in order to form words. In a perfect alphabet, every letter would be a phonetic symbol representing one sound and one only, and each sound would have its appropriate symbol. But it is not the case in English. English spelling is defective. It is a poor reflection of English pronunciation as we have not enough symbols to represent all the sounds of English. The problems of these inconsistencies to foreign and second language learners can not be over- emphasized. This study will look at the historical reasons for this problem; areas of these inconsistencies and make some suggestions to ease the problem of spelling and pronunciation for second and foreign language learners. Introduction: With the spread of literacy and the invention of printing came the development of written English with its confusing and inconsistent spellings becoming more and more apparent. Ideally, the spelling system should closely reflect pronunciation and in many languages that indeed is the case. Each sound of English language is represented by more than one written letter or by sequences of letters; and any letter of English represents more than one sound, or it may not represent any sound at all. There is lack of consistencies. Commenting on these inconsistencies, Vallins (1954) states: 64 African Research Review Vol. 2 (1) Jan., 2008 Professor Ernest Weekly in The English Language forcefully and uncompromisingly expresses the opinion that the spelling of English “is so far as its relation to the spoken word is concerned quite crazy…” At the early stage of writing, say as early as eighteenth century, people did not concern themselves with rules or accepted practices.