Download PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

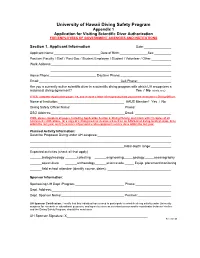

University of Hawaii Diving Safety Program Appendix 1 Application for Visiting Scientific Diver Authorization for EMPLOYEES of GOVERNMENT AGENCIES and INSTITUTIONS

University of Hawaii Diving Safety Program Appendix 1 Application for Visiting Scientific Diver Authorization FOR EMPLOYEES OF GOVERNMENT AGENCIES AND INSTITUTIONS Section 1. Applicant Information Date: Applicant Name: Date of Birth: Sex: Position: Faculty / Staff / Post-Doc / Student Employee / Student / Volunteer / Other: Work Address: Home Phone: Daytime Phone: Email: Cell Phone: Are you a currently active scientific diver in a scientific diving program with which UH recognizes a reciprocal diving agreement? Yes / No (circle one) If YES, complete Application pages 1-4, and include a letter of reciprocity from your home institution’s Diving Officer. Name of Institution: AAUS Member? Yes / No Diving Safety Officer Name: Phone: DSO Address: Email: If NO, please complete all pages, including Application Section 2. Diving History, and return with (1) copies of all referenced certifications, (2) a copy of a diving medical clearance based on an AAUS-level diving medical exam, done within the last year, and (3) evidence of personal scuba equipment service done within the last year. Planned Activity Information: Describe Proposed Diving under UH auspices: Initial depth range: Expected activities (check all that apply): biology/ecology collecting engineering geology oceanography aquaculture archaeology science edu. Equip. placement/monitoring field school attendee (identify course, dates): Sponsor Information: Sponsoring UH Dept./Program: Phone: Dept. Address: Dept. Sponsor Name: Position: UH Sponsor Certification: I certify that this individual has a need to participate in scientific diving activity under University auspices for research or educational purposes, and agree to serve as a contact person and/or coordinator between him/her and the Diving Safety Program, should the need arise. -

Short Update on Dysbaric Osteonecrosis: Concepts and Decompression Management

Dysbaric Osteonecrosis Review Short Update on Dysbaric Osteonecrosis: Concepts and Decompression Management Niladri Kumar Mahato1 Abstract Dysbaric osteonecrosis (DON) is caused by inadequate decompression after exposure to very high ambient air pressures. Different pathological events have been shown to occur in conjunction to result in DON. New observations from clinical and experimental data in this field have led investigators to reformat the etiology, pathogenesis and modify existing modalities of treatment of DON. This short review revisits concepts related to pathophysiology of DON occurring as a part of generalized decompression sickness and discusses newer therapeutic insights stemming from recent advancements in DON research. Keywords: Decompression; Dysbarism; Embolism; Hyperbaric Juxta-articular; Metaphysis; Rhizomelic J Bangladesh Soc Physiol. 2015, December; 10(2): 76-81 For Authors Affiliation, see end of text. http://www.banglajol.info/index.php/JBSP Introduction ysbarism or musculoskeletal pointed towards several etiologies of DON8-13. decompression sickness (DCS) is Given the typical anatomy of vasculature around Dusually observed in people who undergo the end of long bones, it seems plausible that deep-sea diving or are exposed to environments DON is linked to occurrence of micro-embolisms of high air pressures1-5. Dysbarism or Caisson with gas or lipid bubbles following a rapid Disease (CD) is characterized by an array of decrease in surrounding air pressure at those systemic complications involving soft tissues, the sites3,10,14-17. Other investigators have proposed cardio-pulmonary, nervous, renal and external compression of blood flow in such musculoskeletal systems when individuals or vessels due to similar bubbles arising in structures experimental animals are brought back to normal around an artery or a vein to induce external pressure. -

The Effects of Hyperbaric Exposure on Bone Cell Activity in The

Yale University EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale Yale Medicine Thesis Digital Library School of Medicine 1995 The effects of hyperbaric exposure on bone cell activity in the rat : implications for the pathogenesis of dysbaric osteonecrosis Stephanie Anne Kapfer Yale University Follow this and additional works at: http://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ymtdl Recommended Citation Kapfer, Stephanie Anne, "The effects of hyperbaric exposure on bone cell activity in the rat : implications for the pathogenesis of dysbaric osteonecrosis" (1995). Yale Medicine Thesis Digital Library. 2764. http://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ymtdl/2764 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Medicine at EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. It has been accepted for inclusion in Yale Medicine Thesis Digital Library by an authorized administrator of EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. YALE MEDICAL LIBRARY 3 9002 08676 1070 THE EFFECTS OF HYPERBARIC EXPOSURE ON BONE CELL ACTIVITY IN THE RAT; IMPLICATIONS FOR THE PATHOGENESIS OF DYSBARIC OSTEONECROSIS Stephanie Anne YALE UNIVERSITY CUSHING/WHITNEY MEDICAL LIBRARY Permission to photocopy or microfilm processing of this thesis for the purpose of individual scholarly consultation or reference is hereby granted by the author. This permission is not to be interpreted as affecting publication of this work or otherwise placing it in the -

Key Words for Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine

2 Index to Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine for 2009, Volume 39 KEY WORDS FOR DIVING AND HYPERBARIC MEDICINE Abalone Data Gasinduced osmosis Abstracts Deaths Gas solubility Accidents Decompression General interest Adolescents Decompression illness Genitourinary tract Aerobic capacity Decompression sickness Gleanings (from medical journals) Age Deep diving Haematology Air DES – Diver Emergency Service Health Air embolism Diabetes Health status Allergy DIMS Health surveillance Altitude Disabilities Health surveys Anaesthesia Disability Hearing Antarctica Disabled diver Helium pharmacokinetics Arterial gas embolism Diver numbers Hip arthroplasty Ascent Diving History Asthma Diving accidents Human skin equivalent Autobiography Diving at work Hyperbaric facilities Autopsy Diving deaths Hyperbaric oxygen Aviation Diving industry Hyperbaric oxygen therapy Barotrauma Diving organisations Hyperbaric oxygenation Bell diving Diving reflex Hyperbaric research Beta blockade Diving research Hypercapnia Biology Diving safety memos Hyperthermia (see Thermal problems) Blood pressure Diving scholars Hyperventilation Blood substitutes Diving tables Hypothermia (see Thermal problems) Blood sugar level Diving theory (see Physiology) Hypoxia Book reviews Doppler Ice Brain injury Drowning Immersion Breathhold diving Drugs Immunosuppression Bronchial provocation testing Drysuit Incidents Bubbles Dysbaric osteonecrosis Infectious diseases Buccal pumping Ear barotrauma Inflammation Buddies Ear infection Injuries Buoyancy Echocardiography Inner ear Calciphylaxis Ecology -

Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine

Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine The Journal of the South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society (Incorporated in Victoria) A0020660B and the European Underwater and Baromedical Society Volume 42 No. 3 September 2012 HBOT does not improve paediatric autism Diver Emergency Service calls: 17-year Australian experience Methods of monitoring CO2 in ventilated patients compared Australasian Workshop on deep treatment tables for DCI ‘Bubble-free’ diving – do bent divers listen to advice? Diving-related fatalities in Australian waters in 2007 ISSN 1833 3516 Print Post Approved ABN 29 299 823 713 PP 331758/0015 Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine Volume 42 No. 3 September 2012 PURPOSES OF THE SOCIETIES To promote and facilitate the study of all aspects of underwater and hyperbaric medicine To provide information on underwater and hyperbaric medicine To publish a journal and to convene members of each Society annually at a scientific conference SOUTH PACIFIC UNDERWATER EUROPEAN UNDERWATER AND MEDICINE SOCIETY BAROMEDICAL SOCIETY OFFICE HOLDERS OFFICE HOLDERS President President Mike Bennett <[email protected]> Peter Germonpré <[email protected]> Past President Vice President Chris Acott <[email protected]> Costantino Balestra <[email protected]> Secretary Immediate Past President Karen Richardson <[email protected]> Alf Brubakk <[email protected]> Treasurer Past President Shirley Bowen <[email protected]> Noemi Bitterman <[email protected]> Education Officer Honorary Secretary David Smart <[email protected]> -

Diving Physiology 3

Diving Physiology 3 SECTION PAGE SECTION PAGE 3.0 GENERAL ...................................................3- 1 3.3.3.3 Oxygen Toxicity ........................3-21 3.1 SYSTEMS OF THE BODY ...............................3- 1 3.3.3.3.1 CNS: Central 3.1.1 Musculoskeletal System ............................3- 1 Nervous System .........................3-21 3.1.2 Nervous System ......................................3- 1 3.3.3.3.2 Lung and 3.1.3 Digestive System.....................................3- 2 “Whole Body” ..........................3-21 3.2 RESPIRATION AND CIRCULATION ...............3- 2 3.2.1 Process of Respiration ..............................3- 2 3.3.3.3.3 Variations In 3.2.2 Mechanics of Respiration ..........................3- 3 Tolerance .................................3-22 3.2.3 Control of Respiration..............................3- 4 3.3.3.3.4 Benefits of 3.2.4 Circulation ............................................3- 4 Intermittent Exposure..................3-22 3.2.4.1 Blood Transport of Oxygen 3.3.3.3.5 Concepts of and Carbon Dioxide ......................3- 5 Oxygen Exposure 3.2.4.2 Tissue Gas Exchange.....................3- 6 Management .............................3-22 3.2.4.3 Tissue Use of Oxygen ....................3- 6 3.3.3.3.6 Prevention of 3.2.5 Summary of Respiration CNS Poisoning ..........................3-22 and Circulation Processes .........................3- 8 3.2.6 Respiratory Problems ...............................3- 8 3.3.3.3.7 The “Oxygen Clock” 3.2.6.1 Hypoxia .....................................3- -

2009 December

9^k^c\VcY=neZgWVg^XBZY^X^cZKdajbZ(.Cd#)9ZXZbWZg'%%. EJGEDH:HD;I=:HD8>:I>:H IdegdbdiZVcY[VX^a^iViZi]ZhijYnd[VaaVheZXihd[jcYZglViZgVcY]neZgWVg^XbZY^X^cZ Idegdk^YZ^c[dgbVi^dcdcjcYZglViZgVcY]neZgWVg^XbZY^X^cZ IdejWa^h]V_djgcVaVcYidXdckZcZbZbWZghd[ZVX]HdX^ZinVccjVaanViVhX^Zci^ÄXXdc[ZgZcXZ HDJI=E68>;>8JC9:GL6I:G :JGDE:6CJC9:GL6I:G6C9 B:9>8>C:HD8>:IN 76GDB:9>86AHD8>:IN D;;>8:=DA9:GH D;;>8:=DA9:GH EgZh^YZci EgZh^YZci B^`Z7ZccZii 1B#7ZccZii5jchl#ZYj#Vj3 EZiZg<Zgbdceg 1eZiZg#\ZgbdcegZ5ZjWh#dg\3 EVhiçEgZh^YZci K^XZEgZh^YZci 8]g^h6Xdii 1XVXdii5deijhcZi#Xdb#Vj3 8dhiVci^cd7VaZhigV 18dchiVci^cd#7VaZhigV5ZjWh#dg\3 HZXgZiVgn >bbZY^ViZEVhiEgZh^YZci HVgV]AdX`aZn 1hejbhhZXgZiVgn5\bV^a#Xdb3 6a[7gjWV`` 1Va[#WgjWV``5ZjWh#dg\3 IgZVhjgZg EVhiEgZh^YZci ?VcAZ]b 1hejbh#igZVhjgZg5\bV^a#Xdb3 CdZb^7^iiZgbVc 1cdZb^#W^iiZgbVc5ZjWh#dg\3 :YjXVi^dcD[ÄXZg =dcdgVgnHZXgZiVgn 9Vk^YHbVgi 1YVk^Y#hbVgi5Y]]h#iVh#\dk#Vj3 ?dZg\HX]bjio 1_dZg\#hX]bjio5ZjWh#dg\3 EjWa^XD[ÄXZg BZbWZgViAVg\Z'%%. KVcZhhV=VaaZg 1kVcZhhV#]VaaZg5XYbX#Xdb#Vj3 6cYgZVhB©aaZga©``Zc 1VcYgZVh#bdaaZgad``Zc5ZjWh#dg\3 8]V^gbVc6CO=B< BZbWZgViAVg\Z'%%- 9Vk^YHbVgi 1YVk^Y#hbVgi5Y]]h#iVh#\dk#Vj3 9gEZiZg@cZhha 1eZiZg#`cZhha5ZjWh#dg\3 8dbb^iiZZBZbWZgh BZbWZgViAVg\Z'%%, <aZc=Vl`^ch 1lZWbVhiZg5hejbh#dg\#Vj3 E]^a7gnhdc 1e]^a#Wgnhdc5ZjWh#dg\3 HXdiiHfj^gZh 1hXdiiVcYhVcYhfj^gZh5W^\edcY#Xdb3 <jnL^aa^Vbh 1\jnl5^bVe#XX3 69B>C>HIG6I>DC 69B>C>HIG6I>DC BZbWZgh]^e =dcdgVgnIgZVhjgZgBZbWZgh]^eHZXgZiVgn HiZkZ<dWaZ 1VYb^c5hejbh#dg\#Vj3 EVig^X^VLddY^c\ 1eVig^X^VlddY^c\5ZjWh#dg\3 :Y^idg^Va6hh^hiVci &+7jghZab6kZcjZ! C^X`nBXCZ^h] -

Report of the Decompression Illness Adjunctive Therapy Committee of the Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society

REPORT OF THE DECOMPRESSION ILLNESS ADJUNCTIVE THERAPY COMMITTEE OF THE UNDERSEA AND HYPERBARIC MEDICAL SOCIETY Including Proceedings of the Fifty-Third Workshop of the Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society Chaired by Richard E. Moon, MD Editor Richard E. Moon, MD Copyright ©2003 Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society, Inc. 10531 Metropolitan Avenue Kensington, MD 20895, USA ISBN 0-930406-22-2 The views, opinions, and findings contained herein are those of the author(s) and should not be construed as an official Agency position, policy, or decision unless so designated by other official documentation. Authors Richard D. Vann, Ph.D. Assistant Research Professor of Anesthesiology Duke University Medical Center Director of Research, Divers Alert Network Durham, NC 27710 Edward D. Thalmann, M.D. Assistant Clinical Professor of Anesthesiology Assistant Clinical Professor of Occupational and Environmental Medicine Duke University Medical Center Assistant Medical Director, Divers Alert Network Durham, NC 27710 John M. Hardman, M.D. Professor and Chairman Dept. of Pathology John A. Burns School of Medicine University of Hawaii Honolulu, HI 96822 Ward Reed, M.D., M.P.H. Fellow in Undersea and Hyperbaric Medicine Duke University Medical Center Durham, NC 27710 W. Dalton Dietrich, Ph.D. Departments of Neurological Surgery and Neurology The Miami Project to Cure Paralysis University of Miami School of Medicine Miami, FL 33101 Frank Butler, CAPT, MC, USN Biomedical Research Director Naval Special Warfare Command Pensacola, FL Richard E. Moon, M.D. Professor of Anesthesiology Associate Professor of Medicine Medical Director, Center for Hyperbaric Medicine and Environmental Physiology Duke University Medical Center Medical Director, Divers Alert Network Durham, NC 27710 2 Joseph Dervay, M.D., M.M.S., F.A.C.E.P Flight Surgeon Medical Operations and Crew Systems NASA Johnson Space Center Houston, TX 77058 David S. -

Osteonecrosis Occurs in Several Other Clinical Situa- Head in the Elderly

Br J Sports Med: first published as 10.1136/bjsm.9.3.144 on 1 October 1975. Downloaded from 144 DYSBARIC OSTEONECROSIS With A Comment On The Radiological Changes In The Lungs in Decompression Sickness J. K. DAVIDSON Dysbaric osteonecrosis, or caisson disease of bone, is In Britain since 1963 the Decompression Sickness a major hazard to compressed air tunnel workers and an Panel of the Medical Research Council has studied the increasing hazard to divers, especially now that dives are prevalence of dysbaric osteonecrosis in symptom free being made to very much greater depths and for longer men, both in tunnel workers and now in commercial periods. While the acute forms of decompression sick- divers involved in oil exploration in the North Sea. ness - 'the bends' - develop within a few hours follow- Regular radiographic survey examinations include pro- ing decompression, dysbaric osteonecrosis is a late com- jections of both shoulder, hip and knee joints and are plication and it is five months at least, usually a year, carried out at intervals of about one year. The examina- before symptoms develop or radiological changes be- tions are carried out in different parts of the country come apparent. In a typical case a diver may have been and the films are sent to the Decompression Sickness diving to depths of 180 ft. (55 metres) for 18 to 24 Registry in Newcastle-upon-Tyne for interpretation by months without having experienced 'the bends'. Pain in radiologists experienced in the detection of early radio- the shoulder or hip joint may commence quite suddenly logical changes. -

2019 June;49(2)

Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine The Journal of the South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society and the European Underwater and Baromedical Society© Volume 49 No. 2 June 2019 Bullous disease and cerebral arterial gas embolism Does closing a PFO reduce the risk of DCS? A left ventricular assist device in the hyperbaric chamber The impact of health on professional diver attrition Serum tau as a marker of decompression stress Are hypoxia experiences for rebreather divers valuable? Nitrox vs air narcosis measured by critical flicker fusion frequency The effect of medications in diving E-ISSN 2209-1491 ABN 29 299 823 713 CONTENTS Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine Volume 49 No.2 June 2019 Editorials Obituary 77 Risk mitigation in divers with persistent foramen ovale 144 Dr John Knight FANZCA, Dip Peter Wilmshurst DHM, Captain RANR 78 The Editor's offering Original articles SPUMS notices and news 80 The effectiveness of risk mitigation interventions in divers 146 SPUMS Presidents message with persistent (patent) foramen ovale David Smart George Anderson, Douglas Ebersole, Derek Covington, Petar J Denoble 146 ANZHMG Report 88 Serum tau concentration after diving – an observational pilot 147 SPUMS 49th Annual Scientific study Meeting 2020 Anders Rosén, Nicklas Oscarsson, Andreas Kvarnström, Mikael Gennser, Göran Sandström, Kaj Blennow, Helen Seeman-Lodding, Henrik 147 Divers Emergency Service/DAN Zetterberg AP Foundation Telemedicine Scholarship 2019 96 A survey of scuba diving-related injuries and outcomes among French recreational divers 148 Australian -

DESCRIPTIVE CLASSIFICATION of DIVING DISORDERS 4Th Report

EUROPEAN COMMITTEE FOR HYPERBARIC MEDICINE II European Consensus Conference Marseille, 9-11 Mai 1996 DESCRIPTIVE CLASSIFICATION OF DIVING DISORDERS 4th Report Jordi Desola, M.D.,Ph.D. CRIS - Hyperbaric Therapy Unit Barcelona COORDINATING COMMITTEE OF HYPERBARIC MEDICAL CENTRES (CCCMH) Spain Correspondence : Dr. Jordi Desola CRIS - Unitat de Terapèutica Hiperbàrica Dos de maig 301 - (Hospital Creu Roja) - 08025 BARCELONA Tel. +34-935-072-700 - FAX: +34-934-503-736 E-Mail: [email protected] – http://www.CCCMH.com This 4th report includes some important modifications introduced after the 1st preliminary one that was initially edited within the Proceedings Book of the Congress. All diving disciplines are exposed to a high potential of serious accidents, which can be considered inherent to this underwater activity. Some modalities or specialties imply a higher level of hazard, like deep mixed gas-diving in off-shore industry, or cave/speleological diving usually done by divers with a recreational or sport diving licence. Other important risk factor is imposed by the underwater environment which by itself may convert into a tragedy, an incident that would have been irrelevant in the land. This is the case of the people being able to have a normal activity but with a silent or hidden disease that can produce a loss of consciousness underwater. Different etiopathogenic factors are responsible for a quite wide variety of disorders. Some depend on the underwater environment and the physiological mechanisms of adaptation required of the human body. Others are linked to the variation of pressure implicit to any diving activity. Almost all parts of the body can suffer from the consequences of a Diving Disorder (DD), so signs and symptoms can be extremely varied (Table 1). -

Osteonecrosis of the Femoral Head Treatment

ADVERTIMENT. Lʼaccés als continguts dʼaquesta tesi queda condicionat a lʼacceptació de les condicions dʼús establertes per la següent llicència Creative Commons: http://cat.creativecommons.org/?page_id=184 ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis queda condicionado a la aceptación de las condiciones de uso establecidas por la siguiente licencia Creative Commons: http://es.creativecommons.org/blog/licencias/ WARNING. The access to the contents of this doctoral thesis it is limited to the acceptance of the use conditions set by the following Creative Commons license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/?lang=en UNIVERSITAT AUTÒNOMA DE BARCELONA FACULTAT DE MEDICINA DEPARTAMENT DE CIRUGÍA OSTEONECROSIS OF THE FEMORAL HEAD TREATMENT WITH ADVANCED CELL THERAPY AND BIOMATERIALS IN AN EXPERIMENTAL SHEEP ANIMAL MODEL Report presented by Víctor Barro Ojeda to obtain the degree of Doctor in Surgery and Morphological Sciences. Directors: Dr. Màrius Aguirre Canyadell . Advisor: Dr. Roberto Vélez Villa Dr. Enric Cáceres Palou Dr. Enric Cáceres Palou. Barcelona 2018 This research project has been funded by a grant obtained from La Fundació de la Marató de TV3, with the number 201220-30-31, entitled: Tratamiento de la osteonecrosis de cabeza femoral con terapia celular avanzada y biomateriales en un modelo experimental ovino. Acknowledgments To the Vall d'Hebron Hospital and the Department of Orthopedic Surgery and Traumatology for giving me the necessary support for the development of this study. To Vall d'Hebron Research Institute and the Autonomous University of Barcelona for stimulating research in health professionals. To Dr. Enric Cáceres for agreeing to be part of this thesis as a director and for his contributions and suggestions.