Diver, Indigenous Fisherman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lake Huron Scuba Diving

SOUTHERN LAKE ASSESSMENT SOUTHERN RECREATION PROFILE LAKE Scuba Diving: OPPORTUNITIES FOR LAKE HURON ASSESSMENT FINGER LAKES SCUBA LAKES FINGER The southern Lake Huron coast is a fantastic setting for outdoor exploration. Promoting the region’s natural assets can help build vibrant communities and support local economies. This series of fact sheets profiles different outdoor recreation activities that could appeal to residents and visitors of Michigan’s Thumb. We hope this information will help guide regional planning, business develop- ment and marketing efforts throughout the region. Here we focus on scuba diving – providing details on what is involved in the sport, who participates, and what is unique about diving in Lake Huron. WHY DIVE IN LAKE HURON? With wildlife, shipwrecks, clear water and nearshore dives, the waters of southern Lake Huron create a unique environment for scuba divers. Underwater life abounds, including colorful sunfish and unusual species like the longnose gar. The area offers a large collection of shipwrecks, and is home to two of Michigan’s 12 underwater preserves. Many of the wrecks are in close proximity to each other and are easily accessed by charter or private boat. The fresh water of Lake Huron helps to preserve the wrecks better than saltwater, and the lake’s clear water offers excellent visibility – often up to 50 feet! With many shipwrecks at different depths, the area offers dives for recreational as well as technical divers. How Popular is Scuba Diving? Who Scuba Dives? n Scuba diving in New York’s Great Lakes region stimulated more than $108 In 2010, 2.7 million Americans went scuba A snapshot of U.S. -

Download the Full Article As Pdf ⬇︎

AndreaInterview with Donati — Pioneering Technical Diving on Ponza for 30 Years Andrea Donati (left) and his partner, Daniela Spaziani, run Ponza Diving, which is located in the main harbour (above) of Ponza Island in Italy. In my line of work as a dive industry professional, I attend a lot of dive shows and get to meet a lot of people, most of them nice and interesting in various ways. It was also at a dive show in Italy, many years ago, that I first met Andrea Donati and his partner, Daniela Spaziani, of Ponza Diving. I clearly remember my first impression of how sympathetic, unpretentious and genuine the two came across, which scores a lot of points in my book. They appeared competent and organised, and with their operation located in one of the most picturesque locations I have ever seen, it did not take any arm twisting to lure me down there for a visit. Text and photos by Peter Symes future. This profile will be about the virtues driven, and adapting more readily to the accommodate a wider range of requests anchoring it. In hindsight, I now consider of diving Italian-style, as Ponza Diving services we could offer in those times. and needs of customers. mooring essential for a successful dive. The world is dotted with beautiful loca- marks its 30th season. Of course, diving equipment was not We started off with just a 6m dinghy, Year by year, the number of divers tions, and there exist many excellent dive so sophisticated at that time. We dived a compressor and 20 tanks, but already increased, and I kept reinvesting in the operations across the globe that also PS: Please reflect on your three decades only with air, no nitrox, no trimix and no in the first year, I bought another dinghy, operation. -

Diving Safety Manual Revision 3.2

Diving Safety Manual Revision 3.2 Original Document: June 22, 1983 Revision 1: January 1, 1991 Revision 2: May 15, 2002 Revision 3: September 1, 2010 Revision 3.1: September 15, 2014 Revision 3.2: February 8, 2018 WOODS HOLE OCEANOGRAPHIC INSTITUTION i WHOI Diving Safety Manual DIVING SAFETY MANUAL, REVISION 3.2 Revision 3.2 of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution Diving Safety Manual has been reviewed and is approved for implementation. It replaces and supersedes all previous versions and diving-related Institution Memoranda. Dr. George P. Lohmann Edward F. O’Brien Chair, Diving Control Board Diving Safety Officer MS#23 MS#28 [email protected] [email protected] Ronald Reif David Fisichella Institution Safety Officer Diving Control Board MS#48 MS#17 [email protected] [email protected] Dr. Laurence P. Madin John D. Sisson Diving Control Board Diving Control Board MS#39 MS#18 [email protected] [email protected] Christopher Land Dr. Steve Elgar Diving Control Board Diving Control Board MS# 33 MS #11 [email protected] [email protected] Martin McCafferty EMT-P, DMT, EMD-A Diving Control Board DAN Medical Information Specialist [email protected] ii WHOI Diving Safety Manual WOODS HOLE OCEANOGRAPHIC INSTITUTION DIVING SAFETY MANUAL REVISION 3.2, September 5, 2017 INTRODUCTION Scuba diving was first used at the Institution in the summer of 1952. At first, formal instruction and proper information was unavailable, but in early 1953 training was obtained at the Naval Submarine Escape Training Tank in New London, Connecticut and also with the Navy Underwater Demolition Team in St. -

Stepping Into Rebreather Rebreather Diving

SSteptepping into rebreather diving By Paul Beenaround Alex had always been interested in learning to dive with the new breed of closed circuit rebreather’s that had appeared in recent years, so when he was suddenly faced with the choice of a dance weekend in chilly Munich or a week learning to dive with them in the Red Sea it wasn’t a hard decision to make. He was soon on his way with Easyjet flying over the Swiss Alps en-route for Sharm el sheik. Everything went very smoothly and he had soon settled down in the Camel hotel, a slightly upmarket one in the centre of Sharm which was not far from the Red Sea College where he would be doing his rebreather course. The next day he met Sherif, an impish Egyptian who was going to be his mentor for the combined basic and advanced four day course. After some classroom work he was shown the intricate workings of the Poseidon MK6 rebreather, the only one recognised by PADI for recreational sports divers on their recently introduced rebreather course. It was a very complex piece of kit, largely controlled by computer software, which took away the risk of diver error. This is unlike many other versions on the market that had caused accidents and deaths, usually through the diver making a mistake. As nice as it was to know that it was keeping him alive, the Poseidon rebreather’s had had many software problems that largely prevented you either starting a dive or necessitated aborting a dive halfway through for often non-existent faults. -

Download PDF File

Int Marit Health 2020; 71, 1: 71–77 10.5603/IMH.2020.0014 www.intmarhealth.pl ORIGINAL ARTICLE Copyright © 2020 PSMTTM ISSN 1641–9251 Temporary and permanent unfitness of occupational divers. Brest Cohort 2002–2019 from the French National Network for Occupational Disease Vigilance and Prevention (RNV3P) Richard Pougnet1, 2, 3, Laurence Pougnet2, 4, 5, Jean-Dominique Dewitte1, 2, 3, Brice Loddé1, 2, 6, David Lucas1, 2, 6 1Centre for Professional and Environmental Pathologies (Centre de Ressource en Pathologie Professionnelle et Environnementale CRPPE), Brest University Hospital (CHRU), Brest, France 2French Society for Maritime Medicine, France 3Laboratory for Studies and Research in Sociology (LABERS), EA 3149, Faculty of Humanities and Social Science (Faculté de Lettres et Sciences Sociales), Victor Segalen, European University of Brest, Brest, France 4Medical Laboratory, HIA Clermont-Tonnerre, CC41 BCRM Brest, Brest, France 5Host-Pathogen Interaction Study Group (Groupe d’Étude des Interactions Hôte-Pathogène GEIHP), EA 3142, European University of Brest, Brest, France 6Optimization of Physiological Regulations (ORPHY), EA 4324, Faculty of Science and Technology, European University of Brest, Brest, France ABstract Background: In France, the monitoring of professional divers is regulated. Several learned societies (French Occupational Medicine Society, French Hyperbaric Medicine Society and French Maritime Medicine Society) have issued follow-up recommendations for professional divers, including medical follow-up. Medical de- cisions could be temporary unfitness for diving, temporary fitness with monitoring, a restriction of fitness, or permanent unfitness. The aim of study was to point out the causes of unfitness in our centre. Materials and methods: The divers’ files were selected from the French National Network for Occupatio- nal Disease Vigilance and Prevention (RNV3P). -

Excursionsand Diving Adventures

Fishing, Water Sports, Excursions and Diving Adventures Come and join us and experience the incredible range of aquatic activities you can enjoy at Niyama Private Islands. We have high-speed exhilarating adventures to excite you. Wind- powered high intensity sports to propel you across the water! Adventurous fishing trips to catch a magnificent fish for your table! Amazing world-class dive sites awaiting your exploration! Sky-scraping excitement parasailing with a breathtaking bird’s eye view of the stunning islands below you! We offer exciting trips and excursions to discover the fantastic marine life and top side beauty of this amazing archipelago. Snorkel near and far reefs with the resident marine biologist, experience the beauty and freedom of scuba diving for the first time or visit uninhabited islands and isolated Maldivian communities on a voyage of discovery. Then later, when you are looking for more sedate water-based activities, why not rent a kayak and paddle gently around our shallow, protected lagoon or relax in the sun as your captain takes you on a private silent journey by catamaran. Whether you are looking for speed, excitement, relaxation, marine beauty or an opportunity to create that private vision of paradise you have in your mind, then if it is water related, FLOAT can provide it for you. Please contact FLOAT on: Ext. 1270 or Ext. 1395 SCUBA diving Diving At FLOAT, we are simply fanatical about scuba diving. Our aim is to ensure you have a fantastic diving experience during your stay here at Niyama Private Islands. We are blessed with all the necessary elements to create this for you – stunning marine life, fantastic dive sites, warm water and wonderful weather. -

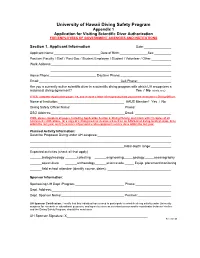

University of Hawaii Diving Safety Program Appendix 1 Application for Visiting Scientific Diver Authorization for EMPLOYEES of GOVERNMENT AGENCIES and INSTITUTIONS

University of Hawaii Diving Safety Program Appendix 1 Application for Visiting Scientific Diver Authorization FOR EMPLOYEES OF GOVERNMENT AGENCIES AND INSTITUTIONS Section 1. Applicant Information Date: Applicant Name: Date of Birth: Sex: Position: Faculty / Staff / Post-Doc / Student Employee / Student / Volunteer / Other: Work Address: Home Phone: Daytime Phone: Email: Cell Phone: Are you a currently active scientific diver in a scientific diving program with which UH recognizes a reciprocal diving agreement? Yes / No (circle one) If YES, complete Application pages 1-4, and include a letter of reciprocity from your home institution’s Diving Officer. Name of Institution: AAUS Member? Yes / No Diving Safety Officer Name: Phone: DSO Address: Email: If NO, please complete all pages, including Application Section 2. Diving History, and return with (1) copies of all referenced certifications, (2) a copy of a diving medical clearance based on an AAUS-level diving medical exam, done within the last year, and (3) evidence of personal scuba equipment service done within the last year. Planned Activity Information: Describe Proposed Diving under UH auspices: Initial depth range: Expected activities (check all that apply): biology/ecology collecting engineering geology oceanography aquaculture archaeology science edu. Equip. placement/monitoring field school attendee (identify course, dates): Sponsor Information: Sponsoring UH Dept./Program: Phone: Dept. Address: Dept. Sponsor Name: Position: UH Sponsor Certification: I certify that this individual has a need to participate in scientific diving activity under University auspices for research or educational purposes, and agree to serve as a contact person and/or coordinator between him/her and the Diving Safety Program, should the need arise. -

Short Update on Dysbaric Osteonecrosis: Concepts and Decompression Management

Dysbaric Osteonecrosis Review Short Update on Dysbaric Osteonecrosis: Concepts and Decompression Management Niladri Kumar Mahato1 Abstract Dysbaric osteonecrosis (DON) is caused by inadequate decompression after exposure to very high ambient air pressures. Different pathological events have been shown to occur in conjunction to result in DON. New observations from clinical and experimental data in this field have led investigators to reformat the etiology, pathogenesis and modify existing modalities of treatment of DON. This short review revisits concepts related to pathophysiology of DON occurring as a part of generalized decompression sickness and discusses newer therapeutic insights stemming from recent advancements in DON research. Keywords: Decompression; Dysbarism; Embolism; Hyperbaric Juxta-articular; Metaphysis; Rhizomelic J Bangladesh Soc Physiol. 2015, December; 10(2): 76-81 For Authors Affiliation, see end of text. http://www.banglajol.info/index.php/JBSP Introduction ysbarism or musculoskeletal pointed towards several etiologies of DON8-13. decompression sickness (DCS) is Given the typical anatomy of vasculature around Dusually observed in people who undergo the end of long bones, it seems plausible that deep-sea diving or are exposed to environments DON is linked to occurrence of micro-embolisms of high air pressures1-5. Dysbarism or Caisson with gas or lipid bubbles following a rapid Disease (CD) is characterized by an array of decrease in surrounding air pressure at those systemic complications involving soft tissues, the sites3,10,14-17. Other investigators have proposed cardio-pulmonary, nervous, renal and external compression of blood flow in such musculoskeletal systems when individuals or vessels due to similar bubbles arising in structures experimental animals are brought back to normal around an artery or a vein to induce external pressure. -

The Effects of Hyperbaric Exposure on Bone Cell Activity in The

Yale University EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale Yale Medicine Thesis Digital Library School of Medicine 1995 The effects of hyperbaric exposure on bone cell activity in the rat : implications for the pathogenesis of dysbaric osteonecrosis Stephanie Anne Kapfer Yale University Follow this and additional works at: http://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ymtdl Recommended Citation Kapfer, Stephanie Anne, "The effects of hyperbaric exposure on bone cell activity in the rat : implications for the pathogenesis of dysbaric osteonecrosis" (1995). Yale Medicine Thesis Digital Library. 2764. http://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ymtdl/2764 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Medicine at EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. It has been accepted for inclusion in Yale Medicine Thesis Digital Library by an authorized administrator of EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. YALE MEDICAL LIBRARY 3 9002 08676 1070 THE EFFECTS OF HYPERBARIC EXPOSURE ON BONE CELL ACTIVITY IN THE RAT; IMPLICATIONS FOR THE PATHOGENESIS OF DYSBARIC OSTEONECROSIS Stephanie Anne YALE UNIVERSITY CUSHING/WHITNEY MEDICAL LIBRARY Permission to photocopy or microfilm processing of this thesis for the purpose of individual scholarly consultation or reference is hereby granted by the author. This permission is not to be interpreted as affecting publication of this work or otherwise placing it in the -

Operation Wallacea Dive Standards

Dive Policy Standards and Procedures 2019 Contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 3 1.1 Definition of a dive ......................................................................................................................... 3 2. Operation Wallacea Dive Standards ...................................................................................... 3 2.1 Maximum bottom time ................................................................................................................... 3 2.2 Maximum depth ............................................................................................................................. 4 2.3 Air requirements ............................................................................................................................ 4 2.4 Safety stops ................................................................................................................................... 4 2.5 Surface interval .............................................................................................................................. 4 2.6 Repetitive diving ............................................................................................................................ 4 2.7 Flying after diving .......................................................................................................................... 5 2.8 Over-profiling ................................................................................................................................ -

Witness to a Rebreather Fatality

Witness to a Rebreather Fatality Copyright ©2008 by Mark Derrick, IANTD CCR Instructor Permission is granted to copy and/or distribute this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License On a pleasant afternoon in March of 2008, off the coast of Hillsboro Beach Florida, I suddenly found myself at the back of a dive boat kneeling over a fellow rebreather diver and administering CPR. This article contains my opinions and speculation about what happened that day, and is offered to help other rebreather divers understand some of the factors that led to the accident. It assumes the reader is familiar with closed-circuit rebreathers. The boat was a commercial dive charter operation and the itinerary was a light technical dive on a wreck followed by a drift dive on a reef. Among the boat passengers were several divers with instructor level ratings, although none were acting in an instruction capacity. Of particular note, the boat captain was an open-circuit (OC) technical diving instructor, and an instructor for DAN’s Diving Emergency Management course. The dive master was a CPR instructor. Also aboard was an experienced technical closed-circuit rebreather (CCR) instructor (myself), along with a non-diving rider who was an OC technical diving instructor. The victim was an experienced OC instructor and semi-closed rebreather (SCR) instructor who had recently received a CCR instructor rating. The first dive was unremarkable except that at conclusion of the first dive, during exit from the water, one of the divers dropped a bailout cylinder. Once all the other divers were aboard, during the surface interval I did a bounce dive to find and recover the cylinder. -

X-Ray Magazine L Issue 63

Member of the dive team training in a Mexican cenote Text by Sergey Baykov Photos by Sergey Baykov and Anna Loznevaya On August 14 in Dahab this year, our team of three divers dived a distance of 10km in eight hours using rebreathers. The purpose of this experiment was a practical test of human capabilities and the per- formance of rebreath- ers on a long dive, while under the influence of physical activity. It was in autumn 2010 that my colleague, Sergey Gorpinyuk, proposed the original idea to me: to dive a distance of 7km. As to a location for the experiment, we chose the colorful Mexican cenotes (caves) because they have long passages, calm current and stable direction. In addition, they have markup distances and many exits. We needed only to mark the way in the caves with guidelines. The rebreather was chosen as a technical means for the realization of the project. I was already certified as a Full 10k on a Rebreather— Making the Long Dive Cave Diver, but at that time, I SERGEY BAYKOV had just begun to dive on closed- circuit devices. Gorpinyuk, at that a good kit with which to embrace with the apparatus in cold water To Mexico cenotes Mexico were comfortable was But, as fate intervened, a long time, had already acquired some the dream. and in overhead environments. Two weeks later we flew to putting it mildly. The air tempera- dive didn’t happen. Firstly, it good experience diving with a After testing the new rebreather Two days we spent under the ice, Mexico.