View of Extended Techniques and Their History As Well to Give a Concise Pedagogical Guide That Explains Each Skill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contemporary Romanian Music for Unaccompanied

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by KU ScholarWorks CONTEMPORARY ROMANIAN MUSIC FOR UNACCOMPANIED CLARINET BY 2009 Cosmin Teodor Hărşian Submitted to the graduate program in the Department of Music and Dance and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. ________________________ Chairperson Committee Members ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ Date defended 04. 21. 2009 The Document Committee for Cosmin Teodor Hărşian certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: CONTEMPORARY ROMANIAN MUSIC FOR UNACCOMPANIED CLARINET Committee: ________________________ Chairperson ________________________ Advisor Date approved 04. 21. 2009 ii ABSTRACT Hărșian, Cosmin Teodor, Contemporary Romanian Music for Unaccompanied Clarinet. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2009. Romanian music during the second half of the twentieth century was influenced by the socio-politic environment. During the Communist era, composers struggled among the official ideology, synchronizing with Western compositional trends of the time, and following their own natural style. With the appearance of great instrumentalists like clarinetist Aurelian Octav Popa, composers began writing valuable works that increased the quality and the quantity of the repertoire for this instrument. Works written for clarinet during the second half of the twentieth century represent a wide variety of styles, mixing elements from Western traditions with local elements of concert and folk music. While the four works discussed in this document are demanding upon one’s interpretative abilities and technically challenging, they are also musically rewarding. iii I wish to thank Ioana Hărșian, Voicu Hărșian, Roxana Oberșterescu, Ilie Oberșterescu and Michele Abbott for their patience and support. -

UTM Clarinet Handbook Spring 2018

UTM Clarinet Handbook Spring 2018 For MUAP 161/162/164/362/363/364: Clarinet Lessons MUAP 395/495: Clarinet Recitals Dr. Liz Aleksander Associate Professor of Clarinet [email protected] Cell: 419.346.8624 Office: 731.881.7413 University of Tennessee at Martin Department of Music Table of Contents Table of Contents Welcome ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 General Information ................................................................................................................................. 6 Faculty Contact Information ......................................................................................................................... 6 Communication Policy.................................................................................................................................... 6 Required Equipment & Maintenance ......................................................................................................... 6 Required & Suggested Texts ......................................................................................................................... 7 Borrowed Items ................................................................................................................................................. 8 Ensemble Auditions ......................................................................................................................................... 8 Auxiliary -

Viva Presenza a Siena Dei Compositori Italiani

**p*r*f*M.r '«unii mnl.n, t^ai «Wii'ia '-«-.•*.-_. *#*.~«--4.»« W . » • •---*fr <<r< » » fc #- »•• *Jk «-H ir».** ••• * v»—..*^ !>• »-—,"• • «» i'»«*-• « 4 >lv .1. .<%*4.«Vi -.4 ìli il ! l'Unita / mereoledì 31 agosto 1977 PAG. 7 / spettacol i - a rie \ » < ^ ur Grande successo alla > Basilica di Massenzio I fatti e i problemi della musica » \ Rai $ •. * .n i * >i In progetto oggi vedremo Viva presenza a Siena *' i s i de, H popolo è lontano, ma i ad Arezzo Incontro con problemi non tanto. Sulla Rete due, dopo la i Taviani nuova puntata del telefilm Al posto del consueto Mer della serie Colombo, alle 22 coledì sport stasera, c'è un va in onda un programma dei compositori italiani un Centro film: e cosi, questa settima anch'esso direttamente lega na, poco manca che ci of to al mondo del cinema. Ful frano un film a sera. Non vio Acciallnl e Lucia Coluc- Eseguite opere di Petrassi, Zafred, Encinar e Berio - Manifesta ce ne lamenteremo troppo, celli, della Cooperativa Cine di studi dal momento che le alterna ma Democratico, parlano del zioni commemorative di Bucchi e Frazzi - Accanto ad interpreti tive, assai spesso, non sono fratelli Taviani, della loro ' già affermati si sono fatti apprezzare i giovani allievi dei corsi entusiasmanti. opera, della loro tematica, del Il film di questa sera, Il loro mezzi espressivi, del lo corali ritorno di Harry Collings (ti ro « messaggi ». tolo originale: The Hired - ' Nel servizio c'è un'ampia Del nostro inviato e l'altro hanno avuto in buo dosi, corrano il rischio di per selezione del film di questi na sorte lo 6tato di grazia di dere tanto fervore. -

International Viola Congress

CONNECTING CULTURES AND GENERATIONS rd 43 International Viola Congress concerts workshops| masterclasses | lectures | viola orchestra Cremona, October 4 - 8, 2016 Calendar of Events Tuesday October 4 8:30 am Competition Registration, Sala Mercanti 4:00 pm Tymendorf-Zamarra Recital, Sala Maffei 9:30 am-12:30 pm Competition Semifinal,Teatro Filo 4:00 pm Stanisławska, Guzowska, Maliszewski 10:00 am Congress Registration, Sala Mercanti Recital, Auditorium 12:30 pm Openinig Ceremony, Auditorium 5:10 pm Bruno Giuranna Lecture-Recital, Auditorium 1:00 pm Russo Rossi Opening Recital, Auditorium 6:10 pm Ettore Causa Recital, Sala Maffei 2:00 pm-5:00 pm Competition Semifinal,Teatro Filo 8:30 pm Competition Final, S.Agostino Church 2:00 pm Dalton Lecture, Sala Maffei Post-concert Café Viola, Locanda il Bissone 3:00 pm AIV General Meeting, Sala Mercanti 5:10 pm Tabea Zimmermann Master Class, Sala Maffei Friday October 7 6:10 pm Alfonso Ghedin Discuss Viola Set-Up, Sala Maffei 9:00 am ESMAE, Sala Maffei 8:30 pm Opening Concert, Auditorium 9:00 am Shore Workshop, Auditorium Post-concert Café Viola, Locanda il Bissone 10:00 am Giallombardo, Kipelainen Recital, Auditorium Wednesday October 5 11:10 am Palmizio Recital, Sala Maffei 12:10 pm Eckert Recital, Sala Maffei 9:00 am Kosmala Workshop, Sala Maffei 9:00 am Cuneo Workshop, Auditorium 12:10 pm Rotterdam/The Hague Recital, Auditorium 10:00 am Alvarez, Richman, Gerling Recital, Sala Maffei 1:00 pm Street Concerts, Various Locations 11:10 am Tabea Zimmermann Recital, Museo del Violino 2:00 pm Viola Orchestra -

A Chinese Clarinet Legend Also in This Issue

Vol. 45 • No. 1 December 2017 Tao AChunxiao: Chinese Clarinet Legend Also in this issue... ClarinetFest® 2017 Report The Genesis of Gustav Jenner’s Clarinet Sonata D’ADDARIO GIVES ME THE FREEDOM TO PRODUCE THE SOUND I HEAR IN MY HEAD. — JONATHAN GUNN REINVENTING CRAFTSMANSHIP FOR THE 21ST CENTURY. President’sThe EDITOR Rachel Yoder [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOR Jessica Harrie [email protected] EDITORIAL BOARD Dear ICA Members, Mitchell Estrin, Heike Fricke, Jessica Harrie, ope you are enjoying a wonderful new season Caroline Hartig, Rachel Yoder of music making with fulflling activities and MUSIC REVIEWS EDITOR events. Many exciting things are happening in Gregory Barrett – [email protected] our organization. Te ICA believes that if you Hdo good things, good things happen! I want to thank everyone AUDIO REVIEWS EDITOR who has contributed to our Capital Campaign. We especially Chris Nichols – [email protected] wish to thank Alan and Janette Stanek for their amazing gift of $11,250.00 to fund our competitions for the coming GRAPHIC DESIGN ClarinetFest® 2018. Te ICA is grateful for your generosity Karry Tomas Graphic Design and the generosity of all Capital Campaign donors. Please [email protected] visit www.youcaring.com/internationalclarinetassociation to Caroline Hartig make your donation today. We would love to hear your story ADVERTISING COORDINATOR and look forward to our continued campaign which will last Elizabeth Crawford – [email protected] through ClarinetFest® 2018. Also, visit www.clarinet.org/ donor-wall to check out our donor wall with many photos and thank-yous to those who INDEX MANAGER contributed to the ICA for ClarinetFest® 2017. -

Il Recupero Dell'antico Nell'opera Di Ottorino

SCUOLA DI DOTTORATO IN STORIA E CRITICA DEI BENI ARTISTICI , MUSICALI E DELLO SPETTACOLO XXII CICLO IL RECUPERO DELL’ANTICO NELL’OPERA DI OTTORINO RESPIGHI E L’ARCHIVIO DOCUMENTARIO ALLA FONDAZIONE “GIORGIO CINI” DI VENEZIA Coordinatore: prof. ALESSANDRO BALLARIN Supervisore: prof. ANTONIO LOVATO Dottoranda: MARTINA BURAN DATA CONSEGNA TESI 30 giugno 2010 2 A Riccardo e Veronica 3 4 INDICE PREMESSA ………………………………………..…………………………..……. p. 9 I. IL FONDO “OTTORINO RESPIGHI ” ………………………………………… » 13 1. Configurazione originaria del fondo ………………………………………… » 14 2. Interventi di riordino …………………………………………………………. » 16 3. Descrizione del contenuto ……………………………………………………. » 20 II. RITRATTO DI OTTORINO RESPIGHI ……………………………..……..... » 31 1. L’infanzia e le prime opere …………………………………………………... » 32 2. I primi passi verso il recupero dell’antico …………………………………… » 35 3. L’incontro con Elsa …………………………………………………………... » 38 4. Le trascrizioni di musiche antiche e Casa Ricordi …………………………... » 40 5. Il “periodo gregoriano” ……………………………………………………... » 42 6. L’incontro con Claudio Guastalla …………………………………………… » 44 7. Le opere ispirate al gregoriano ……………………………………………… » 46 8. La nomina all’Accademia d’Italia e il Manifesto…………………………….. » 48 9. La fiamma e l’elaborazione dell’Orfeo ………………………………………. » 53 10. Lucrezia ……………………………………………………………………... » 58 III. IL CONTESTO ………………………………………..………………...……… » 63 1. Il recupero dell’antico ………………………………………………………... » 63 1.1 La rinascita del gregoriano …………………………………………. » 64 1.2 Angelo De Santi, Giovanni Tebaldini e Lorenzo Perosi ……………. -

The Changing Role of the Bass Clarinet: Support for Its Integration Into the Modern Clarinet Studio

UNLV Theses/Dissertations/Professional Papers/Capstones 5-1-2015 The hC anging Role of the Bass Clarinet: Support for Its Integration into the Modern Clarinet Studio Jennifer Beth Iles University of Nevada, Las Vegas, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Music Commons, and the Performance Studies Commons Repository Citation Iles, Jennifer Beth, "The hC anging Role of the Bass Clarinet: Support for Its Integration into the Modern Clarinet Studio" (2015). UNLV Theses/Dissertations/Professional Papers/Capstones. Paper 2367. This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Scholarship@UNLV. It has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses/ Dissertations/Professional Papers/Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CHANGING ROLE OF THE BASS CLARINET: SUPPORT FOR ITS INTEGRATION INTO THE MODERN CLARINET STUDIO By Jennifer Beth Iles Bachelor of Music Education McNeese State University 2005 Master of Music Performance University of North Texas 2008 A doctoral document submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts Department of Music College of Fine Arts The Graduate College University of Nevada Las Vegas May 2015 We recommend the dissertation prepared under our supervision by Jennifer Iles entitled The Changing Role of the Bass Clarinet: Support for Its Integration into the Modern Clarinet Studio is approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Department of Music Marina Sturm, D.M.A., Committee Chair Cheryl Taranto, Ph.D., Committee Member Stephen Caplan, D.M.A., Committee Member Ken Hanlon, D.M.A., Committee Chair Margot Mink Colbert, B.S., Graduate College Representative Kathryn Hausbeck Korgan, Ph.D., Interim Dean of the Graduate College May 2015 ii ABSTRACT The bass clarinet of the twenty-first century has come into its own. -

EPARM Conference 2020 16-18 April, Royal Academy of Music, London

European Platform for Artistic Research in Music EPARM Conference 2020 16-18 April, Royal Academy of Music, London PROGRAMME Thursday, 16th April Time Activity Location REGISTRATION 13.30 Informal Networking – Coffee available 14:30 – 15:30 Guided Tour of the Academy Opening Event Music Introduction Official Welcome by: 15:45 – 16.30 - Jonathan Freeman-Attwood, Principal of the Royal Dukes Hall Academy of Music - Stefan Gies, CEO of the AEC - Stephen Broad, EPARM Chair Plenary Session I – Keynote by Timothy Jones 16.30 – 17.30 Dukes Hall Moderated by David Gorton 17.30 –18:00 Networking with Refreshments 18:00 – 19:00 Concert 19:00 – 20:00 Reception L8 NITE Performance I A Concert Room Ghost Trance Solo’s: a solo interpretation of Anthony Braxton’s Ghost Trance Music, Kobe Van Cauwenberghe, Royal Conservatoire, Antwerp, Belgium 20:00 – 20:30 L8 NITE Performance I B David Josefowitz Recital Hall Fantasía quasi Sonata: an “in-version” of Beethoven’s Op. 27 No. 2, Luca Chiantore, ESMUC - Escola Superior de Música de Catalunya), Barcelona, Spain L8 NITE Performances I C Angela Burgess Recital Hall LEMUR: Collective Artistic Research within an Ensemble, Francis Michael Duch, NTNU – Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway 20:30 – 20:45 Break to allow room change L8 NITE Performances II A Concert Room Ensemble 1604 presents ...shadows that in darkness dwell…, Timothy Cooper, Royal Conservatoire of Scotland, Glasgow, UK 20:45 – 21:15 L8 NITE Performances II B David Josefowitz Recital Hall Love at first sound: engaging -

Dissertation 3.19.2021

Cultivating the Contemporary Clarinetist: Pedagogical Materials for Extended Clarinet Techniques Caitlin Beare A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts University of Washington 2021 Reading Committee: Timothy Salzman, Chair David Rahbee Benjamin Lulich Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Music © Copyright 2021 Caitlin Beare University of Washington Abstract Cultivating the Contemporary Clarinetist: Pedagogical Materials for Extended Clarinet Techniques Caitlin Beare Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Timothy Salzman School of Music The exploration and implementation of new timbral possibilities and techniques over the past century have redefined approaches to clarinet performance and pedagogy. As the body of repertoire involving nontraditional, or “extended,” clarinet techniques has grown, so too has the pedagogical literature on contemporary clarinet performance, yielding method books, dissertations, articles, and online resources. Despite the wealth of resources on extended clarinet techniques, however, few authors offer accessible pedagogical materials that function as a gateway to learning contemporary clarinet techniques and literature. Consequently, many clarinetists may be deterred from learning a significant portion of the repertoire from the past six decades, impeding their musical development. The purpose of this dissertation is to contribute to the pedagogical literature pertaining to extended clarinet techniques. The document consists of two main sections followed by two appendices. The first section (chapters 1-2) contains an introduction and a literature review of extant resources on extended clarinet techniques published between 1965–2020. This literature review forms the basis of the compendium of materials, found in Appendix A of this document, which aims to assist performers and teachers in searching for and selecting pedagogical materials involving extended clarinet techniques. -

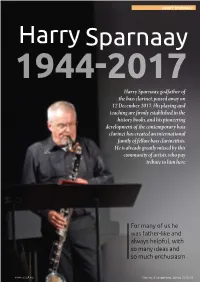

For Many of Us He Was Father-Like and Always Helpful, with So Many Ideas and So Much Enthusiasm

HARRY SPARNAAY Harry Sparnaay 1944-2017 Harry Sparnaay, godfather of the bass clarinet, passed away on 12 December 2017. His playing and teaching are firmly established in the history books, and his pioneering development of the contemporary bass clarinet has created an international family of fellow bass clarinettists. He is already greatly missed by this community of artists, who pay tribute to him here For many of us he was father-like and always helpful, with so many ideas and so much enthusiasm www.cassgb.org Clarinet & Saxophone, Spring 2018 13 HARRY SPARNAAY I think he said yes to everything, and assumed he’d figure out a way to do it, or a convincing way to fake it Oğuz Büyükberber Laura Carmichael (Netherlands/Turkey) (Netherlands) I moved to a new country in the midst Our dear Harry Sparnaay is gone from of my career at the age of 30, to study this world. What an important person with Harry after hearing him play a solo in my life. He was the reason I came to recital in Ostend. The things I learned The Netherlands in 1999, and studying from him go way beyond just the bass bass clarinet with him changed the clarinet. He keeps being a true inspiration course of my life in so many ways. His and a reminder for me when I feel lost or spirit, fortitude and knowledge will live disheartened. on in me and so many other people he At our first meeting, I asked Harry what touched. he thought about my visual impairment in The people he loved were like his relation to the conservatory curriculum. -

The Clarinet Choir Music of Russell S

Vol. 47 • No. 2 March 2020 — 2020 ICA HONORARY MEMBERS — Ani Berberian Henri Bok Deborah Chodacki Paula Corley Philippe Cuper Stanley Drucker Larry Guy Francois Houle Seunghee Lee Andrea Levine Robert Spring Charles West Michael Lowenstern Anthony McGill Ricardo Morales Clarissa Osborn Felix Peikli Milan Rericha Jonathan Russell Andrew Simon Greg Tardy Annelien Van Wauwe Michele VonHaugg Steve Williamson Yuan Yuan YaoGuang Zhai Interview with Robert Spring | Rediscovering Ferdinand Rebay Part 3 A Tribute to the Hans Zinner Company | The Clarinet Choir Music of Russell S. Howland Life Without Limits Our superb new series of Chedeville Clarinet mouthpieces are made in the USA to exacting standards from the finest material available. We are excited to now introduce the new ‘Chedeville Umbra’ and ‘Kaspar CB1’ Clarinet Barrels, the first products in our new line of high quality Clarinet Accessories. Chedeville.com President’sThe EDITOR Rachel Yoder [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOR Dear ICA Members, Jessica Harrie [email protected] t is once again time for the membership to vote in the EDITORIAL BOARD biennial ICA election of officers. You will find complete Mitchell Estrin, Heike Fricke, Denise Gainey, information about the slate of candidates and voting Jessica Harrie, Rachel Yoder instructions in this issue. As you may know, the ICA MUSIC REVIEWS EDITOR bylaws were amended last summer to add the new position Gregory Barrett I [email protected] of International Vice President to the Executive Board. This position was added in recognition of the ICA initiative to AUDIO REVIEWS EDITOR engage and cultivate more international membership and Kip Franklin [email protected] participation. -

PREMIO VALENTINO BUCCHI Parole E Musica Per L'unità Dei Popoli PROGRAMMA: Il Violino Nel 20° E 21°Secolo Prova Eliminator

PREMIO VALENTINO BUCCHI Parole e Musica per l’Unità dei Popoli PROGRAMMA: Il violino nel 20° e 21°secolo Prova eliminatoria I candidati dovranno presentare due pezzi, di autori diversi, di cui uno a scelta dal Gruppo A; Il pezzo obbligatorio - V. Bucchi, Concerto lirico per violino e archi, riduzione per violino e pianoforte (edizione Premio Valentino Bucchi 1993, Via Ubaldino Peruzzi 20, 00139 Roma); - un pezzo a scelta per violino solo, composto e pubblicato nel 20° o nel 21° secolo, di un musicista della stessa nazionalità del candidato. Di questa composizione i candidati dovranno inviare tre copie insieme alla domanda d’iscrizione al concorso. Gruppo A: C. Debussy, Sonate pour violon et piano (Durand, Paris o Peters, London); P. Hindemith, Sonate für Violine allein, Op. 31 n. 1 o n. 2 (Schott’s Söhne, Mainz); E. A. Ysaye, Sonate pour violon seul, Op. 27, n. 3 o n. 6 (Schott Frères, Bruxelles). N.B. - I concorrenti dovranno eseguire le composizioni sopra citate, integralmente o in parte, ad insindacabile giudizio della giuria. Prova semifinale I candidati dovranno presentare tre pezzi di diverso autore scelti rispettivamente: uno dal gruppo A, un secondo dal gruppo B e un terzo dal gruppo C. Gruppo A: B. Bartók, Sonate pour violon et piano n. 1 o n. 2 (Universal, Wien); B. Britten, Three pieces for Violin and Piano, dalla Suite Op. 6 (Boosey & Hawkes, London); L. Dallapiccola, Due studi per violino e pianoforte (Suvini Zerboni, Milano); F. Martin, Sonate, violon et piano, 1931/32 (Universal,Wien); B. Martinu, Sonate pour violon et piano (Salabert, Paris); O.