Novel Graph Processor Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soft Machines Targets Ipcbottleneck

SOFT MACHINES TARGETS IPC BOTTLENECK New CPU Approach Boosts Performance Using Virtual Cores By Linley Gwennap (October 27, 2014) ................................................................................................................... Coming out of stealth mode at last week’s Linley Pro- president/CTO Mohammad Abdallah. Investors include cessor Conference, Soft Machines disclosed a new CPU AMD, GlobalFoundries, and Samsung as well as govern- technology that greatly improves performance on single- ment investment funds from Abu Dhabi (Mubdala), Russia threaded applications. The new VISC technology can con- (Rusnano and RVC), and Saudi Arabia (KACST and vert a single software thread into multiple virtual threads, Taqnia). Its board of directors is chaired by Global Foun- which it can then divide across multiple physical cores. dries CEO Sanjay Jha and includes legendary entrepreneur This conversion happens inside the processor hardware Gordon Campbell. and is thus invisible to the application and the software Soft Machines hopes to license the VISC technology developer. Although this capability may seem impossible, to other CPU-design companies, which could add it to Soft Machines has demonstrated its performance advan- their existing CPU cores. Because its fundamental benefit tage using a test chip that implements a VISC design. is better IPC, VISC could aid a range of applications from Without VISC, the only practical way to improve single-thread performance is to increase the parallelism Application (sequential code) (instructions per cycle, or IPC) of the CPU microarchi- Single Thread tecture. Taken to the extreme, this approach results in massive designs such as Intel’s Haswell and IBM’s Power8 OS and Hypervisor that deliver industry-leading performance but waste power Standard ISA and die area. -

Computer Architecture Out-Of-Order Execution

Computer Architecture Out-of-order Execution By Yoav Etsion With acknowledgement to Dan Tsafrir, Avi Mendelson, Lihu Rappoport, and Adi Yoaz 1 Computer Architecture 2013– Out-of-Order Execution The need for speed: Superscalar • Remember our goal: minimize CPU Time CPU Time = duration of clock cycle × CPI × IC • So far we have learned that in order to Minimize clock cycle ⇒ add more pipe stages Minimize CPI ⇒ utilize pipeline Minimize IC ⇒ change/improve the architecture • Why not make the pipeline deeper and deeper? Beyond some point, adding more pipe stages doesn’t help, because Control/data hazards increase, and become costlier • (Recall that in a pipelined CPU, CPI=1 only w/o hazards) • So what can we do next? Reduce the CPI by utilizing ILP (instruction level parallelism) We will need to duplicate HW for this purpose… 2 Computer Architecture 2013– Out-of-Order Execution A simple superscalar CPU • Duplicates the pipeline to accommodate ILP (IPC > 1) ILP=instruction-level parallelism • Note that duplicating HW in just one pipe stage doesn’t help e.g., when having 2 ALUs, the bottleneck moves to other stages IF ID EXE MEM WB • Conclusion: Getting IPC > 1 requires to fetch/decode/exe/retire >1 instruction per clock: IF ID EXE MEM WB 3 Computer Architecture 2013– Out-of-Order Execution Example: Pentium Processor • Pentium fetches & decodes 2 instructions per cycle • Before register file read, decide on pairing Can the two instructions be executed in parallel? (yes/no) u-pipe IF ID v-pipe • Pairing decision is based… On data -

Performance of a Computer (Chapter 4) Vishwani D

ELEC 5200-001/6200-001 Computer Architecture and Design Fall 2013 Performance of a Computer (Chapter 4) Vishwani D. Agrawal & Victor P. Nelson epartment of Electrical and Computer Engineering Auburn University, Auburn, AL 36849 ELEC 5200-001/6200-001 Performance Fall 2013 . Lecture 1 What is Performance? Response time: the time between the start and completion of a task. Throughput: the total amount of work done in a given time. Some performance measures: MIPS (million instructions per second). MFLOPS (million floating point operations per second), also GFLOPS, TFLOPS (1012), etc. SPEC (System Performance Evaluation Corporation) benchmarks. LINPACK benchmarks, floating point computing, used for supercomputers. Synthetic benchmarks. ELEC 5200-001/6200-001 Performance Fall 2013 . Lecture 2 Small and Large Numbers Small Large 10-3 milli m 103 kilo k 10-6 micro μ 106 mega M 10-9 nano n 109 giga G 10-12 pico p 1012 tera T 10-15 femto f 1015 peta P 10-18 atto 1018 exa 10-21 zepto 1021 zetta 10-24 yocto 1024 yotta ELEC 5200-001/6200-001 Performance Fall 2013 . Lecture 3 Computer Memory Size Number bits bytes 210 1,024 K Kb KB 220 1,048,576 M Mb MB 230 1,073,741,824 G Gb GB 240 1,099,511,627,776 T Tb TB ELEC 5200-001/6200-001 Performance Fall 2013 . Lecture 4 Units for Measuring Performance Time in seconds (s), microseconds (μs), nanoseconds (ns), or picoseconds (ps). Clock cycle Period of the hardware clock Example: one clock cycle means 1 nanosecond for a 1GHz clock frequency (or 1GHz clock rate) CPU time = (CPU clock cycles)/(clock rate) Cycles per instruction (CPI): average number of clock cycles used to execute a computer instruction. -

Chap01: Computer Abstractions and Technology

CHAPTER 1 Computer Abstractions and Technology 1.1 Introduction 3 1.2 Eight Great Ideas in Computer Architecture 11 1.3 Below Your Program 13 1.4 Under the Covers 16 1.5 Technologies for Building Processors and Memory 24 1.6 Performance 28 1.7 The Power Wall 40 1.8 The Sea Change: The Switch from Uniprocessors to Multiprocessors 43 1.9 Real Stuff: Benchmarking the Intel Core i7 46 1.10 Fallacies and Pitfalls 49 1.11 Concluding Remarks 52 1.12 Historical Perspective and Further Reading 54 1.13 Exercises 54 CMPS290 Class Notes (Chap01) Page 1 / 24 by Kuo-pao Yang 1.1 Introduction 3 Modern computer technology requires professionals of every computing specialty to understand both hardware and software. Classes of Computing Applications and Their Characteristics Personal computers o A computer designed for use by an individual, usually incorporating a graphics display, a keyboard, and a mouse. o Personal computers emphasize delivery of good performance to single users at low cost and usually execute third-party software. o This class of computing drove the evolution of many computing technologies, which is only about 35 years old! Server computers o A computer used for running larger programs for multiple users, often simultaneously, and typically accessed only via a network. o Servers are built from the same basic technology as desktop computers, but provide for greater computing, storage, and input/output capacity. Supercomputers o A class of computers with the highest performance and cost o Supercomputers consist of tens of thousands of processors and many terabytes of memory, and cost tens to hundreds of millions of dollars. -

CPU) the CPU Is the Brains of the Computer, and Is Also Known As the Processor (A Single Chip Also Known As Microprocessor)

Central processing unit (CPU) The CPU is the brains of the computer, and is also known as the processor (a single chip also known as microprocessor). This electronic component interprets and carries out the basic instructions that operate the computer. Cache as a rule holds data waiting to be processed and instructions waiting to be executed. The main parts of the CPU are: control unit arithmetic logic unit (ALU), and registers – also referred as Cache registers The CPU is connected to a circuit board called the motherboard also known as the system board. Click here to see more information on the CPU Let’s look inside the CPU and see what the different components actually do and how they interact Control unit The control unit directs and co-ordinates most of the operations in the computer. It is a bit similar to a traffic officer controlling traffic! It translates instructions received from a program/application and then begins the appropriate action to carry out the instruction. Specifically the control unit: controls how and when input devices send data stores and retrieves data to and from specific locations in memory decodes and executes instructions sends data to other parts of the CPU during operations sends data to output devices on request Arithmetic Logic Unit (ALU): The ALU is the computer’s calculator. It handles all math operations such as: add subtract multiply divide logical decisions - true or false, and/or, greater then, equal to, or less than Registers Registers are special temporary storage areas on the CPU. They are: used to store items during arithmetic, logic or transfer operations. -

Reverse Engineering X86 Processor Microcode

Reverse Engineering x86 Processor Microcode Philipp Koppe, Benjamin Kollenda, Marc Fyrbiak, Christian Kison, Robert Gawlik, Christof Paar, and Thorsten Holz, Ruhr-University Bochum https://www.usenix.org/conference/usenixsecurity17/technical-sessions/presentation/koppe This paper is included in the Proceedings of the 26th USENIX Security Symposium August 16–18, 2017 • Vancouver, BC, Canada ISBN 978-1-931971-40-9 Open access to the Proceedings of the 26th USENIX Security Symposium is sponsored by USENIX Reverse Engineering x86 Processor Microcode Philipp Koppe, Benjamin Kollenda, Marc Fyrbiak, Christian Kison, Robert Gawlik, Christof Paar, and Thorsten Holz Ruhr-Universitat¨ Bochum Abstract hardware modifications [48]. Dedicated hardware units to counter bugs are imperfect [36, 49] and involve non- Microcode is an abstraction layer on top of the phys- negligible hardware costs [8]. The infamous Pentium fdiv ical components of a CPU and present in most general- bug [62] illustrated a clear economic need for field up- purpose CPUs today. In addition to facilitate complex and dates after deployment in order to turn off defective parts vast instruction sets, it also provides an update mechanism and patch erroneous behavior. Note that the implementa- that allows CPUs to be patched in-place without requiring tion of a modern processor involves millions of lines of any special hardware. While it is well-known that CPUs HDL code [55] and verification of functional correctness are regularly updated with this mechanism, very little is for such processors is still an unsolved problem [4, 29]. known about its inner workings given that microcode and the update mechanism are proprietary and have not been Since the 1970s, x86 processor manufacturers have throughly analyzed yet. -

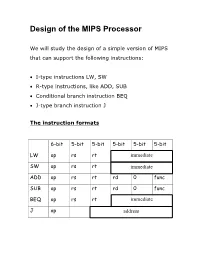

Design of the MIPS Processor

Design of the MIPS Processor We will study the design of a simple version of MIPS that can support the following instructions: • I-type instructions LW, SW • R-type instructions, like ADD, SUB • Conditional branch instruction BEQ • J-type branch instruction J The instruction formats 6-bit 5-bit 5-bit 5-bit 5-bit 5-bit LW op rs rt immediate SW op rs rt immediate ADD op rs rt rd 0 func SUB op rs rt rd 0 func BEQ op rs rt immediate J op address ALU control ALU control (3-bit) 32 ALU result 32 ALU control input ALU function 000 AND 001 OR 010 add 110 sub 111 Set less than How to generate the ALU control input? The control unit first generates this from the opcode of the instruction. A single-cycle MIPS We consider a simple version of MIPS that uses Harvard architecture. Harvard architecture uses separate memory for instruction and data. Instruction memory is read-only – a programmer cannot write into the instruction memory. To read from the data memory, set Memory read =1 To write into the data memory, set Memory write =1 Instruction fetching Clock Each clock cycle fetches the instruction from the address specified by the PC, and increments PC by 4 at the same time. Executing R-type instructions This is the instruction format for the R-type instructions. Here are the steps in the execution of an R-type instruction: ♦ Read instruction ♦ Read source registers rs and rt ♦ ALU performs the desired operation ♦ Store result in the destination register rd. -

1. Central Processing Unit (CPU): 2. Memory Unit

Department of Electrical Engineering. First Year / 2016-2017 By: Salwa Adel Al-agha Lecture 2 1. Central Processing Unit (CPU): The Central Processing Unit (CPU) is an internal component of the computer, portion of a computer system that carries out the instructions of a computer program, to perform the basic arithmetical, logical, and input/output operations of the system. The CPU is the brain of the computer. On personal computers and small workstations, the CPU is housed in a single silicon chip called a microprocessor. Modern CPUs are large scale integrated circuits in small, rectangular packages, with multiple connecting pins. Two typical components of a CPU are: - Arithmetic Logic Unit (ALU). - Control Unit (CU). Modern CPUs are small and square and contain multiple metallic connectors or pins on the underside. Pentium chip or processor, made by Intel, is the most common CPU though there are many other companies that produce processors for personal computers. 2. Memory Unit: Memory is a collection of storage registers used to transfer information in and out of the unit. Memory is one of the easiest pieces of hardware to add to computer. The actual work is done in (memory) and the finished result is stored in (disk). The information stored in the memory as binary code in groups of bits called word. The binary is two logic levels: - Logic (1). - Logic (0). Bit: is binary digit (1) or (0), and Byte: is a group of eight bits. 9 Department of Electrical Engineering. First Year / 2016-2017 By: Salwa Adel Al-agha Lecture 2 Memory in general is divided into two general categories: 2.1 Read Only Memory: Read-Only Memory (ROM) is a class of storage medium used in computers and other electronic devices. -

Evaluation of Synthesizable CPU Cores

Evaluation of synthesizable CPU cores DANIEL MATTSSON MARCUS CHRISTENSSON Maste r ' s Thesis Com p u t e r Science an d Eng i n ee r i n g Pro g r a m CHALMERS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Depart men t of Computer Engineering Gothe n bu r g 20 0 4 All rights reserved. This publication is protected by law in accordance with “Lagen om Upphovsrätt, 1960:729”. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the authors. Daniel Mattsson and Marcus Christensson, Gothenburg 2004. Evaluation of synthesizable CPU cores Abstract The three synthesizable processors: LEON2 from Gaisler Research, MicroBlaze from Xilinx, and OpenRISC 1200 from OpenCores are evaluated and discussed. Performance in terms of benchmark results and area resource usage is measured. Different aspects like usability and configurability are also reviewed. Three configurations for each of the processors are defined and evaluated: the comparable configuration, the performance optimized configuration and the area optimized configuration. For each of the configurations three benchmarks are executed: the Dhrystone 2.1 benchmark, the Stanford benchmark suite and a typical control application run as a benchmark. A detailed analysis of the three processors and their development tools is presented. The three benchmarks are described and motivated. Conclusions and results in terms of benchmark results, performance per clock cycle and performance per area unit are discussed and presented. Sammanfattning De tre syntetiserbara processorerna: LEON2 från Gaisler Research, MicroBlaze från Xilinx och OpenRISC 1200 från OpenCores utvärderas och diskuteras. -

Microprocessor Packaging (Intel)

MicroprocessorMicroprocessor PackagingPackaging The Key Link in the Chain Koushik Banerjee Technical Advisor Assembly Technology Development Intel Corporation 1 MicroprocessorsMicroprocessors 1971 2001 2 GlobalGlobal PackagingPackaging R&DR&D China Shanghai Philippines Cavite Arizona Chandler Malaysia Penang VirtualVirtual ATDATD 3 MainMain R&DR&D facilityfacility inin Chandler,Chandler, AZAZ 4 Computing needs driving complexity First to introduce organic in mainstream CPUs First to introduce flip chip in Intel 486TM Pentium®mainstreamPentium® Pro Pentium® CPUs II Pentium® III Pentium® 4 Itanium® Processor Processor Processor Processor Processor Processor Processor 25 MHz 1.0+ GHz Ceramic Wire-bond To Organic To Flip Chip 5 LookingLooking aheadahead …… ComplexityComplexity andand ChallengesChallenges toto supportsupport Moore’sMoore’s LawLaw 1. Silicon to package interconnect 2. Within package interconnect 3. Power management 4. Adding more functionality GoalGoal :: BringBring technologytechnology innovationinnovation intointo HighHigh volumevolume manufacturingmanufacturing atat aa LOWLOW COSTCOST 6 SiliconSilicon ?? PackagePackage RelationshipRelationship AnatomyAnatomy 101101 Silicon Processor: The “brain” of the computer (generates instructions) Packaging: The rest of the body (Communicates instructions to the outside world, adds protection) NoNo PackagePackage == NoNo ProductProduct !! Great Packaging = Great Products !! Great Packaging = Great Products !! 7 TheThe KeyKey LinkLink inin thethe ChainChain OpportunityOpportunity Transistor-to-Transistor -

Scientific Computing Kernels on the Cell Processor

Scientific Computing Kernels on the Cell Processor Samuel Williams, John Shalf, Leonid Oliker Shoaib Kamil, Parry Husbands, Katherine Yelick Computational Research Division Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Berkeley, CA 94720 {swwilliams,jshalf,loliker,sakamil,pjrhusbands,kayelick}@lbl.gov ABSTRACT architectures that provide high performance on scientific ap- The slowing pace of commodity microprocessor performance plications, yet have a healthy market outside the scientific improvements combined with ever-increasing chip power de- community. In this work, we examine the potential of the mands has become of utmost concern to computational sci- recently-released STI Cell processor as a building block for entists. As a result, the high performance computing com- future high-end computing systems, by investigating perfor- munity is examining alternative architectures that address mance across several key scientific computing kernels: dense the limitations of modern cache-based designs. In this work, matrix multiply, sparse matrix vector multiply, stencil com- we examine the potential of using the recently-released STI putations on regular grids, as well as 1D and 2D FFTs. Cell processor as a building block for future high-end com- Cell combines the considerable floating point resources re- puting systems. Our work contains several novel contribu- quired for demanding numerical algorithms with a power- tions. First, we introduce a performance model for Cell and efficient software-controlled memory hierarchy. Despite its apply it to several key scientific computing kernels: dense radical departure from previous mainstream/commodity pro- matrix multiply, sparse matrix vector multiply, stencil com- cessor designs, Cell is particularly compelling because it putations, and 1D/2D FFTs. The difficulty of programming will be produced at such high volumes that it will be cost- Cell, which requires assembly level intrinsics for the best competitive with commodity CPUs. -

Tms320c54x DSP Functional Overview

TMS320C54xt DSP Functional Overview Literature Number: SPRU307A September 1998 – Revised May 2000 Printed on Recycled Paper TMS320C54x DSP Functional Overview This document provides a functional overview of the devices included in the Texas Instrument TMS320C54xt generation of digital signal processors. Included are descriptions of the central processing unit (CPU) architecture, bus structure, memory structure, on-chip peripherals, and the instruction set. Detailed descriptions of device-specific characteristics such as package pinouts, package mechanical data, and device electrical characteristics are included in separate device-specific data sheets. Topic Page 1.1 Features. 2 1.2 Architecture. 7 1.3 Bus Structure. 13 1.4 Memory. 15 1.5 On-Chip Peripherals. 22 1.5.1 Software-Programmable Wait-State Generators. 22 1.5.2 Programmable Bank-Switching . 22 1.5.3 Parallel I/O Ports. 22 1.5.4 Direct Memory Access (DMA) Controller. 23 1.5.5 Host-Port Interface (HPI). 27 1.5.6 Serial Ports. 30 1.5.7 General-Purpose I/O (GPIO) Pins. 34 1.5.8 Hardware Timer. 34 1.5.9 Clock Generator. 34 1.6 Instruction Set Summary. 36 1.7 Development Support. 47 1.8 Documentation Support. 50 TMS320C54x DSP Functional Overview 1 Features 1.1 Features Table 1–1 provides an overview the TMS320C54x, TMS320LC54x, and TMS320VC54x fixed-point, digital signal processor (DSP) families (hereafter referred to as the ’54x unless otherwise specified). The table shows significant features of each device, including the capacity of on-chip RAM and ROM, the available peripherals, the CPU speed, and the type of package with its total pin count.