Evolution of Whales from Land to Sea1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JVP 26(3) September 2006—ABSTRACTS

Neoceti Symposium, Saturday 8:45 acid-prepared osteolepiforms Medoevia and Gogonasus has offered strong support for BODY SIZE AND CRYPTIC TROPHIC SEPARATION OF GENERALIZED Jarvik’s interpretation, but Eusthenopteron itself has not been reexamined in detail. PIERCE-FEEDING CETACEANS: THE ROLE OF FEEDING DIVERSITY DUR- Uncertainty has persisted about the relationship between the large endoskeletal “fenestra ING THE RISE OF THE NEOCETI endochoanalis” and the apparently much smaller choana, and about the occlusion of upper ADAM, Peter, Univ. of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA; JETT, Kristin, Univ. of and lower jaw fangs relative to the choana. California, Davis, Davis, CA; OLSON, Joshua, Univ. of California, Los Angeles, Los A CT scan investigation of a large skull of Eusthenopteron, carried out in collaboration Angeles, CA with University of Texas and Parc de Miguasha, offers an opportunity to image and digital- Marine mammals with homodont dentition and relatively little specialization of the feeding ly “dissect” a complete three-dimensional snout region. We find that a choana is indeed apparatus are often categorized as generalist eaters of squid and fish. However, analyses of present, somewhat narrower but otherwise similar to that described by Jarvik. It does not many modern ecosystems reveal the importance of body size in determining trophic parti- receive the anterior coronoid fang, which bites mesial to the edge of the dermopalatine and tioning and diversity among predators. We established relationships between body sizes of is received by a pit in that bone. The fenestra endochoanalis is partly floored by the vomer extant cetaceans and their prey in order to infer prey size and potential trophic separation of and the dermopalatine, restricting the choana to the lateral part of the fenestra. -

The World at the Time of Messel: Conference Volume

T. Lehmann & S.F.K. Schaal (eds) The World at the Time of Messel - Conference Volume Time at the The World The World at the Time of Messel: Puzzles in Palaeobiology, Palaeoenvironment and the History of Early Primates 22nd International Senckenberg Conference 2011 Frankfurt am Main, 15th - 19th November 2011 ISBN 978-3-929907-86-5 Conference Volume SENCKENBERG Gesellschaft für Naturforschung THOMAS LEHMANN & STEPHAN F.K. SCHAAL (eds) The World at the Time of Messel: Puzzles in Palaeobiology, Palaeoenvironment, and the History of Early Primates 22nd International Senckenberg Conference Frankfurt am Main, 15th – 19th November 2011 Conference Volume Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung IMPRINT The World at the Time of Messel: Puzzles in Palaeobiology, Palaeoenvironment, and the History of Early Primates 22nd International Senckenberg Conference 15th – 19th November 2011, Frankfurt am Main, Germany Conference Volume Publisher PROF. DR. DR. H.C. VOLKER MOSBRUGGER Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung Senckenberganlage 25, 60325 Frankfurt am Main, Germany Editors DR. THOMAS LEHMANN & DR. STEPHAN F.K. SCHAAL Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum Frankfurt Senckenberganlage 25, 60325 Frankfurt am Main, Germany [email protected]; [email protected] Language editors JOSEPH E.B. HOGAN & DR. KRISTER T. SMITH Layout JULIANE EBERHARDT & ANIKA VOGEL Cover Illustration EVELINE JUNQUEIRA Print Rhein-Main-Geschäftsdrucke, Hofheim-Wallau, Germany Citation LEHMANN, T. & SCHAAL, S.F.K. (eds) (2011). The World at the Time of Messel: Puzzles in Palaeobiology, Palaeoenvironment, and the History of Early Primates. 22nd International Senckenberg Conference. 15th – 19th November 2011, Frankfurt am Main. Conference Volume. Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung, Frankfurt am Main. pp. 203. -

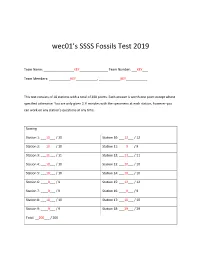

Wec01's SSSS Fossils Test 2019

wec01’s SSSS Fossils Test 2019 Team Name: _________________KEY________________ Team Number: ___KEY___ Team Members: ____________KEY____________, ____________KEY____________ This test consists of 18 stations with a total of 200 points. Each answer is worth one point except where specified otherwise. You are only given 2 ½ minutes with the specimens at each station, however you can work on any station’s questions at any time. Scoring Station 1: ___10___ / 10 Station 10: ___12___ / 12 Station 2: ___10___ / 10 Station 11: ____9___ / 9 Station 3: ___11___ / 11 Station 12: ___11___ / 11 Station 4: ___10___ / 10 Station 13: ___10___ / 10 Station 5: ___10___ / 10 Station 14: ___10___ / 10 Station 6: ____9___ / 9 Station 15: ___12___ / 12 Station 7: ____9___ / 9 Station 16: ____9___ / 9 Station 8: ___10___ / 10 Station 17: ___10___ / 10 Station 9: ____9___ / 9 Station 18: ___29___ / 29 Total: __200___ / 200 Team Number: _KEY_ Station 1: Dinosaurs (10 pt) 1. Identify the genus of specimen A Tyrannosaurus (1 pt) 2. Identify the genus of specimen B Stegosaurus (1 pt) 3. Identify the genus of specimen C Allosaurus (1 pt) 4. Which specimen(s) (A, B, or C) are A, C (1 pt) Saurischians? 5. Which two specimens (A, B, or C) lived at B, C (1 pt) the same time? 6. Identify the genus of specimen D Velociraptor (1 pt) 7. Identify the genus of specimen E Coelophysis (1 pt) 8. Which specimen (D or E) is commonly E (1 pt) found in Ghost Ranch, New Mexico? 9. Which specimen (A, B, C, D, or E) would D (1 pt) specimen F have been found on? 10. -

A New Middle Eocene Protocetid Whale (Mammalia: Cetacea: Archaeoceti) and Associated Biota from Georgia Author(S): Richard C

A New Middle Eocene Protocetid Whale (Mammalia: Cetacea: Archaeoceti) and Associated Biota from Georgia Author(s): Richard C. Hulbert, Jr., Richard M. Petkewich, Gale A. Bishop, David Bukry and David P. Aleshire Source: Journal of Paleontology , Sep., 1998, Vol. 72, No. 5 (Sep., 1998), pp. 907-927 Published by: Paleontological Society Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1306667 REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1306667?seq=1&cid=pdf- reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms SEPM Society for Sedimentary Geology and are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Paleontology This content downloaded from 131.204.154.192 on Thu, 08 Apr 2021 18:43:05 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms J. Paleont., 72(5), 1998, pp. 907-927 Copyright ? 1998, The Paleontological Society 0022-3360/98/0072-0907$03.00 A NEW MIDDLE EOCENE PROTOCETID WHALE (MAMMALIA: CETACEA: ARCHAEOCETI) AND ASSOCIATED BIOTA FROM GEORGIA RICHARD C. HULBERT, JR.,1 RICHARD M. PETKEWICH,"4 GALE A. -

Thomas Jefferson Meg Tooth

The ECPHORA The Newsletter of the Calvert Marine Museum Fossil Club Volume 30 Number 3 September 2015 Thomas Jefferson Meg Tooth Features Thomas Jefferson Meg The catalogue number Review; Walking is: ANSP 959 Whales Inside The tooth came from Ricehope Estate, Snaggletooth Shark Cooper River, Exhibit South Carolina. Tiktaalik Clavatulidae In 1806, it was Juvenile Bald Eagle originally collected or Sculpting Whale Shark owned by Dr. William Moroccan Fossils Reid. Prints in the Sahara Volunteer Outing to Miocene-Pliocene National Geographic coastal plain sediments. Dolphins in the Chesapeake Sloth Tooth Found SharkFest Shark Iconography in Pre-Columbian Panama Hippo Skulls CT- Scanned Squalus sp. Teeth Sperm Whale Teeth On a recent trip to the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University (Philadelphia), Collections Manager Ned Gilmore gave John Nance and me a behind -the-scenes highlights tour. Among the fossils that belonged to Thomas☼ Jefferson (left; American Founding Father, principal author of the Declaration of Independence, and third President of the United States) was this Carcharocles megalodon tooth. Jefferson’s interests and knowledge were encyclopedic; a delight to know that they included paleontology. Hand by J. Nance. Photo by S. Godfrey. Jefferson portrait from: http://www.biography.com/people/thomas-jefferson-9353715 ☼ CALVERT MARINE MUSEUM www.calvertmarinemuseum.com 2 The Ecphora September 2015 Book Review: The Walking 41 million years ago and has worldwide distribution. It was fully aquatic, although it did have residual Whales hind limbs. In later chapters, Professor Thewissen George F. Klein discusses limb development and various genetic factors that make whales, whales. This is a The full title of this book is The Walking complicated topic, but I found these chapters very Whales — From Land to Water in Eight Million clear and readable. -

Intervertebral and Epiphyseal Fusion in the Postnatal Ontogeny of Cetaceans and Terrestrial Mammals

J Mammal Evol DOI 10.1007/s10914-014-9256-7 ORIGINAL PAPER Intervertebral and Epiphyseal Fusion in the Postnatal Ontogeny of Cetaceans and Terrestrial Mammals Meghan M. Moran & Sunil Bajpai & J. Craig George & Robert Suydam & Sharon Usip & J. G. M. Thewissen # Springer Science+Business Media New York 2014 Abstract In this paper we studied three related aspects of the Introduction ontogeny of the vertebral centrum of cetaceans and terrestrial mammals in an evolutionary context. We determined patterns The vertebral column provides support for the body and of ontogenetic fusion of the vertebral epiphyses in bowhead allows for flexibility and mobility (Gegenbaur and Bell whale (Balaena mysticetus) and beluga whale 1878;Hristovaetal.2011; Bruggeman et al. 2012). To (Delphinapterus leucas), comparing those to terrestrial mam- achieve this mobility, individual vertebrae articulate with each mals and Eocene cetaceans. We found that epiphyseal fusion other through cartilaginous intervertebral joints between the is initiated in the neck and the sacral region of terrestrial centra and synovial joints between the pre- and post- mammals, while in recent aquatic mammals epiphyseal fusion zygapophyses. The mobility of each vertebral joint varies is initiated in the neck and caudal regions, suggesting loco- greatly between species as well as along the vertebral column motor pattern and environment affect fusion pattern. We also within a single species. Vertebral column mobility greatly studied bony fusion of the sacrum and evaluated criteria used impacts locomotor style, whether the animal is terrestrial or to homologize cetacean vertebrae with the fused sacrum of aquatic. In aquatic Cetacea, buoyancy counteracts gravity, and terrestrial mammals. We found that the initial ossification of the tail is the main propulsive organ (Fish 1996;Fishetal. -

Constraints on the Timescale of Animal Evolutionary History

Palaeontologia Electronica palaeo-electronica.org Constraints on the timescale of animal evolutionary history Michael J. Benton, Philip C.J. Donoghue, Robert J. Asher, Matt Friedman, Thomas J. Near, and Jakob Vinther ABSTRACT Dating the tree of life is a core endeavor in evolutionary biology. Rates of evolution are fundamental to nearly every evolutionary model and process. Rates need dates. There is much debate on the most appropriate and reasonable ways in which to date the tree of life, and recent work has highlighted some confusions and complexities that can be avoided. Whether phylogenetic trees are dated after they have been estab- lished, or as part of the process of tree finding, practitioners need to know which cali- brations to use. We emphasize the importance of identifying crown (not stem) fossils, levels of confidence in their attribution to the crown, current chronostratigraphic preci- sion, the primacy of the host geological formation and asymmetric confidence intervals. Here we present calibrations for 88 key nodes across the phylogeny of animals, rang- ing from the root of Metazoa to the last common ancestor of Homo sapiens. Close attention to detail is constantly required: for example, the classic bird-mammal date (base of crown Amniota) has often been given as 310-315 Ma; the 2014 international time scale indicates a minimum age of 318 Ma. Michael J. Benton. School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1RJ, U.K. [email protected] Philip C.J. Donoghue. School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1RJ, U.K. [email protected] Robert J. -

Functional Morphology of the Vertebral Column in Remingtonocetus (Mammalia, Cetacea) and the Evolution of Aquatic Locomotion in Early Archaeocetes

Functional Morphology of the Vertebral Column in Remingtonocetus (Mammalia, Cetacea) and the Evolution of Aquatic Locomotion in Early Archaeocetes by Ryan Matthew Bebej A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ecology and Evolutionary Biology) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor Philip D. Gingerich, Co-Chair Professor Philip Myers, Co-Chair Professor Daniel C. Fisher Professor Paul W. Webb © Ryan Matthew Bebej 2011 To my wonderful wife Melissa, for her infinite love and support ii Acknowledgments First, I would like to thank each of my committee members. I will be forever grateful to my primary mentor, Philip D. Gingerich, for providing me the opportunity of a lifetime, studying the very organisms that sparked my interest in evolution and paleontology in the first place. His encouragement, patience, instruction, and advice have been instrumental in my development as a scholar, and his dedication to his craft has instilled in me the importance of doing careful and solid research. I am extremely grateful to Philip Myers, who graciously consented to be my co-advisor and co-chair early in my career and guided me through some of the most stressful aspects of life as a Ph.D. student (e.g., preliminary examinations). I also thank Paul W. Webb, for his novel thoughts about living in and moving through water, and Daniel C. Fisher, for his insights into functional morphology, 3D modeling, and mammalian paleobiology. My research was almost entirely predicated on cetacean fossils collected through a collaboration of the University of Michigan and the Geological Survey of Pakistan before my arrival in Ann Arbor. -

Fallen in a Dead Ear: Intralabyrinthine Preservation of Stapes in Fossil Artiodactyls Maeva Orliac, Guillaume Billet

Fallen in a dead ear: intralabyrinthine preservation of stapes in fossil artiodactyls Maeva Orliac, Guillaume Billet To cite this version: Maeva Orliac, Guillaume Billet. Fallen in a dead ear: intralabyrinthine preservation of stapes in fossil artiodactyls. Palaeovertebrata, 2016, 40 (1), 10.18563/pv.40.1.e3. hal-01897786 HAL Id: hal-01897786 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01897786 Submitted on 17 Oct 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/297725060 Fallen in a dead ear: intralabyrinthine preservation of stapes in fossil artiodactyls Article · March 2016 DOI: 10.18563/pv.40.1.e3 CITATIONS READS 2 254 2 authors: Maeva Orliac Guillaume Billet Université de Montpellier Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle 76 PUBLICATIONS 745 CITATIONS 103 PUBLICATIONS 862 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: The ear region of Artiodactyla View project Origin, evolution, and dynamics of Amazonian-Andean ecosystems View project All content following this page was uploaded by Maeva Orliac on 14 March 2016. -

Currently Zygorhiza Kochii; Mammalia, Cetacea): Proposed Replacement of the Holotype by a Neotype

Case 3611Basilosaurus kochii Reichenbach, 1847 (currently Zygorhiza kochii; Mammalia, Cetacea): proposed replacement of the holotype by a neotype Author: Uhen, Mark D. Source: The Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature, 70(2) : 103-107 Published By: International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature URL: https://doi.org/10.21805/bzn.v70i2.a14 BioOne Complete (complete.BioOne.org) is a full-text database of 200 subscribed and open-access titles in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Complete website, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/terms-of-use. Usage of BioOne Complete content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non - commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Downloaded From: https://bioone.org/journals/The-Bulletin-of-Zoological-Nomenclature on 08 Apr 2021 Terms of Use: https://bioone.org/terms-of-use Access provided by Auburn University Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature 70(2) June 2013 103 Case 3611 Basilosaurus kochii Reichenbach, 1847 (currently Zygorhiza kochii; Mammalia, Cetacea): proposed replacement of the holotype by a neotype Mark D. Uhen Department of Atmospheric, Oceanic, and Earth Sciences, George Mason University, MS 5F2, Fairfax, VA 22030, U.S.A. (e-mail: [email protected]) Abstract. -

Transition of Eocene Whales from Land to Sea: Evidence from Bone Microstructure

RESEARCH ARTICLE Transition of Eocene Whales from Land to Sea: Evidence from Bone Microstructure Alexandra Houssaye1,2*, Paul Tafforeau3, Christian de Muizon4, Philip D. Gingerich5 1 UMR 7179 CNRS/Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Département Ecologie et Gestion de la Biodiversité, Paris, France, 2 Steinmann Institut für Geologie, Paläontologie und Mineralogie, Universität Bonn, Bonn, Germany, 3 European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, Grenoble, France, 4 Sorbonne Universités, CR2P—CNRS, MNHN, UPMC-Paris 6, Département Histoire de la Terre, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France, 5 Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences and Museum of Paleontology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States of America a11111 * [email protected] Abstract Cetacea are secondarily aquatic amniotes that underwent their land-to-sea transition during OPEN ACCESS the Eocene. Primitive forms, called archaeocetes, include five families with distinct degrees Citation: Houssaye A, Tafforeau P, de Muizon C, of adaptation to an aquatic life, swimming mode and abilities that remain difficult to estimate. Gingerich PD (2015) Transition of Eocene Whales The lifestyle of early cetaceans is investigated by analysis of microanatomical features in from Land to Sea: Evidence from Bone postcranial elements of archaeocetes. We document the internal structure of long bones, Microstructure. PLoS ONE 10(2): e0118409. ribs and vertebrae in fifteen specimens belonging to the three more derived archaeocete doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0118409 families — Remingtonocetidae, Protocetidae, and Basilosauridae — using microtomogra- Academic Editor: Brian Lee Beatty, New York phy and virtual thin-sectioning. This enables us to discuss the osseous specializations ob- Institute of Technology College of Osteopathic Medicine, UNITED STATES served in these taxa and to comment on their possible swimming behavior. -

Locomotor Evolution in the Earliest Cetaceans: Functional Model, Modem Analogues, and Paleontological Evidence

Paleobiology, 23(4), 1997, pp. 482-490 Locomotor evolution in the earliest cetaceans: functional model, modem analogues, and paleontological evidence J. G. M. Thewissen and E E. Fish Abstract.-We discuss a model for the origin of cetacean swimming that is based on hydrodynamic and kinematic data of modem mammalian swimmers. The model suggests that modem otters (Mustelidae: Lutrinae) display several of the locomotor modes that early cetaceans used at different stages in the transition from land to water. We use mustelids and other amphibious mammals to analyze the morphology of the Eocene cetacean Ambulocetus natans, and we conclude that Ambu- locetus may have locomoted by a combination of pelvic paddling and dorsoventral undulations of the tail, and that its locomotor mode in water resembled that of the modem otter Lutra most closely. We also suggest that cetacean locomotion may have resembled that of the freshwater otter Pteronuru at a stage beyond Ambulocetus. 1. G. M. Thewissen. Department qf Anatomy, Northeastern Ohio Universities College of Medicine. Roots- town, Ohio 44242 E E. Fish Department of Biology, West Chester Unrwrsrty. West Chester, Pmnsvlmnia 19380 Accepted. 7 July 1997 Introduction that wen the earliest whales had adopted modem ways of swimming. In spite of noting The locomotor morphology of terrestrial differences in overall morphology and muscle mammals is very different from that of aquatic development, Kellogg (1936) proposed that mammals. The musculoskeletal system of swimming mammals displays conspicuous late Eocene Basilosaurus had a tail fluke and specializations that can be considered as ad- implied that it swam by dorsoventral oscilla- aptations for life in the water.