A History of Early Coprolite Research Christopher J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Parkinson His Life and Times His1dry of Neuroscience

JAMES PARKINSON HIS LIFE AND TIMES HIS1DRY OF NEUROSCIENCE Series Editors Louise Marshall F. Clifford Rose Brain Research Institute Charing Cross & Westminster University of California Medical School Los Angeles University of London JAMES PARKINSON HIS UFE AND TIMES By A.D. Morris F. Clifford Rose Editor Birkhauser Boston Basel Berlin F. Clifford Rose University of London Charing Cross & Westminster Medical School The Reynolds Building London W6 8RP, England Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Morris, Arthur D. james Parkinson: his life and times I A_D. Morris; edited by F. Clifford Rose with a foreword by john Thackray_ p_ cm_ - (History of neuroscience) Bibliography: p_ L Parkinson,james, 1755-1824_ 2_ Neurologists- Great Britain Biography_ I. Title_ II. Series: History of neuroscience (Boston, Mass_) [DNLM: L Parkinson,james, 1755-1824_ 2_ Neurology-biography_ WZ 100 P245M] RC339_52_P376M67 1989 616_8'0092'4 - dc19 [B] DNLMIDLC 88-36582 Printed on acid-free paper © Birkhauser Boston, 1989 Soft cover reprint of the hardcoverlst edition 1989 All rights reserved_ No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the copyright owner_ Typeset by Publishers Service, Bozeman, Montana_ ISBN-13: 978-0-8176-3401-8 me-ISBN-13 :978-1-4615-9824-4 DOl: 10_1 007/978-1-4615-9824-4 Preface Dr. A. D. Morris had a long interest in, and great familiarity with, the life and times of James Parkinson (1755-1824). He was an avid collector of material related to Parkinson, some of which he communicated to medi· cal and historical groups, and which he also incorporated into publica· tions, especially his admirable work, The Hoxton Madhouses. -

CSMS General Assembly Thursday, December 20, 7:00 PM Annual

Colorado Springs Mineralogical Society Founded in 1936 Lazard Cahn Honorary President December 2018 PICK&PACK Vol 58 .. Number #10 Inside this Issue: CSMS General Assembly CSMS Calendar Pg. 2 Kansas Pseudo- Morphs: Pg. 4 Thursday, December 20, 7:00 PM Limonite After Pyrite Duria Antiquior: A Annual Christmas Party 19th Century Fore- Pg. 7 runner of Paleoart CSMS Rockhounds of Pg. 9 the Year & 10 Pebble Pups Pg10 **In case of inclement weather, please call** Secretary’s Spot Pg11 Mt. Carmel Veteran’s Service Center 719 309-4714 Classifieds Pg17 Annual Christmas Party Details Please mark your calendars and plan to attend the annual Christmas Party at the Mt. Carmel Veteran's Service Center.on Thursday, December 20, at 7PM. We will provide roast turkey and baked ham as well as Bill Arnson's chili. Members whose last names begin with A--P, please bring a side dish to share. Those whose last names begin with Q -- Z, please bring a dessert to share. There will be a gift exchange for those who want to participate. Please bring a wrapped hobby-related gift valued at $10.00 or less to exchange. We will have a short business meeting to vote on some bylaw changes, and to elect next year's Board of Directors. The Board candidates are as follows: President: Sharon Holte Editor: Taylor Harper Vice President: John Massie Secretary: ?????? Treasurer: Ann Proctor Member-at-Large: Laurann Briding Membership Secretary: Adelaide Barr Member-at Large: Bill Arnson Past president: Ernie Hanlon We are in desperate need of a secretary to serve on the Board. -

Formal and Informal Networks of Knowledge and Etheldred Benett's

Journal of Literature and Science Volume 8, No. 1 (2015) ISSN 1754-646X Susan Pickford, “Social Authorship, Networks of Knowledge”: 69-85 “I have no pleasure in collecting for myself alone”:1 Social Authorship, Networks of Knowledge and Etheldred Benett’s Catalogue of the Organic Remains of the County of Wiltshire (1831) Susan Pickford As with many other fields of scientific endeavour, the relationship between literature and geology has proved a fruitful arena for research in recent years. Much of this research has focused on the founding decades of the earth sciences in the early- to mid-nineteenth century, with recent articles by Gowan Dawson and Laurence Talairach-Vielmas joining works such as Noah Heringman’s Romantic Rocks, Aesthetic Geology (2003), Ralph O’Connor’s The Earth on Show: Fossils and the Poetics of Popular Science, 1802-1856 (2007), Virginia Zimmerman’s Excavating Victorians (2008) and Adelene Buckland’s Novel Science: Fiction and the Invention of Nineteenth-Century Geology (2013), to explore the rhetorical and narrative strategies of writings in the early earth sciences. It has long been noted that the most institutionally influential early geologists formed a cohort of eager young men who, having no tangible interests in the economic and practical applications of their chosen field, were in a position to develop a passionately Romantic engagement with nature, espousing an apocalyptic rhetoric of catastrophes past and borrowing epic imagery from Milton and Dante (Buckland 9, 14-15). However, as Buckland further notes, this argument – though persuasive as far as it goes – fails to take into account the broad social range of participants in the construction of early geological knowledge. -

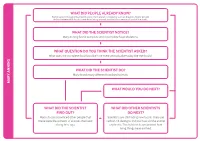

What Did the Scientist Notice? What Question Do You Think

WHAT DID PEOPLE ALREADY KNOW? Some people thought that fossils came from ancient creatures such as dragons. Some people did not believe that fossils came from living animals or plants but were just part of the rocks. WHAT DID THE SCIENTIST NOTICE? Mary Anning found complete and incomplete fossil skeletons. WHAT QUESTION DO YOU THINK THE SCIENTIST ASKED? What does the complete fossil look like? Are there animals alive today like the fossils? WHAT DID THE SCIENTIST DO? Mary found many different fossilised animals. MARY ANNING MARY WHAT WOULD YOU DO NEXT? WHAT DID THE SCIENTIST WHAT DID OTHER SCIENTISTS FIND OUT? DO NEXT? Mary’s fossils convinced other people that Scientists are still finding new fossils. They use these were the remains of animals that lived carbon-14 dating to find out how old the animal a long time ago. or plant is. This helps us to understand how living things have evolved. s 1823 / 1824 1947 Mary Anning (1823) discovered a nearly complete plesiosaur Carbon-14 dating enables scientists to determine the age of a formerly skeleton at Lyme Regis. living thing more accurately. When a Tail fossils of a baby species William Conybeare (1824) living organism dies, it stops taking in of Coelurosaur, fully People often found fossils on the beach described Mary’s plesiosaur to the new carbon. Measuring the amount preserved in amber including and did not know what they were, so Geographical Society. They debated of 14C in a fossil sample provides soft tissue, were found in 2016 BEFORE 1800 BEFORE gave them interesting names such as whether it was a fake, but Mary was information that can be used to Myanmar. -

Mary Anning (1799 – 1847) Was One of the First Fossil Collectors

Geology Section: history, interests and the importance of Devon‟s geology Malcolm Hart [Vice-Chair Geology Section] School of Geography, Earth & Environmental Sciences, University of Plymouth Devonshire Association, Forum, Sidmouth, March 2020 Slides: 3 – 13 South-West England people; 14 – 25 Our northward migration; 24 – 33 Climate change: a modern problem; 34 – 50 Our geoscience heritage: Jurassic Coast World Heritage Site and the English Riviera UNESCO Global Geopark; 51 – 53 Summary and perspectives When we look at the natural landscape it can appear almost un- changing – even in the course of a life- time. William Smith (1769–1839) was a practical engineer, who used geology in an applied way. He recognised that the fossils he found could indicate the „stratigraphy‟ of the rocks that his work encountered. His map was produced in 1815. Images © Geological Society of London Mary Anning (1799 – 1847) was one of the first fossil collectors. At the time the area was being quarried, though features such as the „ammonite pavement‟ were left for science. Image © Geological Society of London Images © National Museum, Wales Sir Henry De La Beche (1796‒1855) was an extraordinary individual. He wrote on the geology of Devon, Cornwall and Somerset, while living in Lyme Regis. He studied the local geology and created, in Duria Antiquior (a more ancient Dorset) the first palaeoecological reconstruction. He was often ridiculed for this! He was also the first Director of the British Geological Survey. His suggestion, in 1839, that the rocks of Devonshire and Cornwall were „distinctive‟ led to the creation of the Devonian System in 1840. -

James Parkinson 1755-I824

MUTISH MEDICAL 9 1973 601 BRITISH MEDICAL JOURNAL 9 JUNE 1973 601 Medical History Br Med J: first published as 10.1136/bmj.2.5866.601 on 9 June 1973. Downloaded from James Parkinson 1755-I824 MICHAEL JEFFERSON British Medical journal, 1973, 2, 601-603 Formative Years Of his schooling there is no direct record, but from his own comments it evidently included solid grounding in Greek and Since Parkinsonism is a topic of wide medical interest it is as well as natural philosophy (that is, natural to feel curiousity about the life and character of the Latin mathematics, and biology), and some knowledge of man who was the founder of it all, James Parkinson. An physics, chemistry, with the dead languages was a vital ac- obvious source for biographical material might seem to lie in French. Familiarity the texts of many ancient medical contemporary obituaries, yet this turns out to be a false complishment, because expectation for, in fact, the leading medical jounals of the authorities still widely read and admied, from Hippocrates day-the Medico-Chirurgical Review, the London Medical and Galen onwards, were not available in English translation, though by the end of the eighteenth century the emergent pres- and Physical Yournal, and the London Medical Repository- sure new of all kinds was beginning made no reference to his death, although all had given flattering of scientific knowledge to is there real evidence of his attention a few years earlier to his Essay on the Shaking Palsy. eclipse their importance. Nor that he was apprenticed Or again as a beginning, one might search for a portrait of medical education. -

Origin and Beyond

EVOLUTION ORIGIN ANDBEYOND Gould, who alerted him to the fact the Galapagos finches ORIGIN AND BEYOND were distinct but closely related species. Darwin investigated ALFRED RUSSEL WALLACE (1823–1913) the breeding and artificial selection of domesticated animals, and learned about species, time, and the fossil record from despite the inspiration and wealth of data he had gathered during his years aboard the Alfred Russel Wallace was a school teacher and naturalist who gave up teaching the anatomist Richard Owen, who had worked on many of to earn his living as a professional collector of exotic plants and animals from beagle, darwin took many years to formulate his theory and ready it for publication – Darwin’s vertebrate specimens and, in 1842, had “invented” the tropics. He collected extensively in South America, and from 1854 in the so long, in fact, that he was almost beaten to publication. nevertheless, when it dinosaurs as a separate category of reptiles. islands of the Malay archipelago. From these experiences, Wallace realized By 1842, Darwin’s evolutionary ideas were sufficiently emerged, darwin’s work had a profound effect. that species exist in variant advanced for him to produce a 35-page sketch and, by forms and that changes in 1844, a 250-page synthesis, a copy of which he sent in 1847 the environment could lead During a long life, Charles After his five-year round the world voyage, Darwin arrived Darwin saw himself largely as a geologist, and published to the botanist, Joseph Dalton Hooker. This trusted friend to the loss of any ill-adapted Darwin wrote numerous back at the family home in Shrewsbury on 5 October 1836. -

Mary Anning of Lyme Regis: 19Th Century Pioneer in British Palaeontology

Headwaters Volume 26 Article 14 2009 Mary Anning of Lyme Regis: 19th Century Pioneer in British Palaeontology Larry E. Davis College of St. Benedict / St. John's University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/headwaters Part of the Geology Commons, and the Paleontology Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Larry E. (2009) "Mary Anning of Lyme Regis: 19th Century Pioneer in British Palaeontology," Headwaters: Vol. 26, 96-126. Available at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/headwaters/vol26/iss1/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Headwaters by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LARRY E. DAVIS Mary Anning of Lyme Regis 19th Century Pioneer in British Palaeontology Ludwig Leichhardt, a 19th century German explorer noted in a letter, “… we had the pleasure of making the acquaintance of the Princess of Palaeontology, Miss Anning. She is a strong, energetic spinster of about 28 years of age, tanned and masculine in expression …” (Aurousseau, 1968). Gideon Mantell, a 19th century British palaeontologist, made a less flattering remark when he wrote in his journal, “… sallied out in quest of Mary An- ning, the geological lioness … we found her in a little dirt shop with hundreds of specimens piled around her in the greatest disorder. She, the presiding Deity, a prim, pedantic vinegar looking female; shred, and rather satirical in her conversation” (Curwin, 1940). Who was Mary Anning, this Princess of Palaeontology and Geological Lioness (Fig. -

Teacher's Booklet

Ideas and Evidence at the Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences Teacher’s Booklet Acknowledgements Shawn Peart Secondary Consultant Annette Shelford Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences Paul Dainty Great Cornard Upper School Sarah Taylor St. James Middle School David Heap Westley Middle School Thanks also to Dudley Simons for photography and processing of the images of objects and exhibits at the Sedgwick Museum, and to Adrienne Mayor for kindly allowing us to use her mammoth and monster images (see picture credits). Picture Credits Page 8 “Bag of bones” activity adapted from an old resource, source unknown. Page 8 Iguanodon images used in the interpretation of the skeleton picture resource from www.dinohunters.com Page 9 Mammoth skeleton images from ‘The First Fossil Hunters’ by Adrienne Mayor, Princeton University Press ISBN: 0-691-05863 with kind permission of the author Page 9 Both paintings of Mary Anning from the collections of the Natural History Museum © Natural History Museum, London 1 Page 12 Palaeontologists Picture from the photographic archive of the Sedgwick Museum © Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences Page 14 Images of Iguanodon from www.dinohunters.com Page 15 “Duria Antiquior - a more ancient Dorsetshire” by Henry de la Beche from the collection of the National Museums and Galleries of Wales © National Museum of Wales Page 17 Images of Deinotherium giganteum skull cast © Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences Page 19 Image of red sandstone slab © Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences 2 Introduction Ideas and evidence was introduced as an aspect of school science after the review of the National Curriculum in 2000. Until the advent of the National Strategy for Science it was an area that was often not planned for explicitly. -

Aspects of the History of Parkinson's Disease

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.52.Suppl.6 on 1 June 1989. Downloaded from Journal ofNeurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. Special Supplement 1989:6-10 Aspects of the history of Parkinson's disease J M S PEARCE From the Department ofNeurology and Parkinson's disease Clinic, Hull Royal Infirmary, Hull, UK ASPECTS OF THE HISTORY OF PARKINSON'S AN DISEASE Aspects ofthe history ofParkinson's disease E S SAY Before James Parkinson's classic' "An Essay on the Shaking Palsy" (1817) ancient books recorded many types of paralytic disorders and tremors. None fully ON THa described the distinctive features of the syndrome which so justly perpetuates Parkinson's name. His essay (fig 1) mentioned the earlier writings of Juncker who distinguished tremors, either "Active- SHAKING PALSY. sudden affections of the mind, terror, anger or, Passive -dependant on debilitating causes such as advanced Protected by copyright. age, palsy etc." He credited Sylvius de la Boe for showing the important difference between rest (tremor coactus) and action tremor in 1680. Parkin- BY son cites Sauvages "the tremulous parts leap, and as it wereL vibrate, even when supported: whilst every other JAMES PARKINSON, tremor, he observes, ceases, when the voluntary exer- HUSER OI THE ROYTAL COLLEGE of SUEGEOHI tionfor moving the limb stops ... but returns when we will the limb to move;" He also referred to van Swieten (1749) who had made similar observations about rest tremor. Sauvages had described the festi- LONDON: hant gait which "I think cannot be more fitly named PRINTtD BY WHIrTIGHAW AND ROWLAND. than hastening or hurrying Scelotyrbe (scelotyrbem festinantem, seufestiniam) ", as did Gaubius some ten FOR SHERWOOD, NEELY, AND JONES, years earlier (1758). -

James Parkinson: the Many Many the Parkinson: James

VOLUME 21, ISSUE 1 • 2017 • EDITORS, CARLO COLOSIMO, MD AND MARK STACY, MD In This Issue A 200 Year Celebration of James Parkinson 1st PAS Congress Highlights MDS LEAP: A Mentoring Program NEW! MDS Educational Roadmap New MDS PSP Criteria James Parkinson: The Many Facets of an Enlightened Man Details on page 6 2nd Pan American Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders Congress JUNE 22-24, 2018 MIAMI, FLORIDA, USA Milwaukee, WI Milwaukee, Permit No. Permit Milwaukee, WI 53202-3823 USA 53202-3823 WI Milwaukee, PAID 555 East Wells Street, Suite 1100 Suite Street, Wells East 555 US Postage US International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society Disorder Movement and Parkinson International Non-Profit Org. Non-Profit SAVE THE DATE 2nd Pan American Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders Congress JUNE 22-24, 2018 MIAMI, FLORIDA, USA www.pascongress2018.org Table of Contents 4 Editorial: Carlo Colosimo, MD and Mark Stacy, MD OFFICERS (2015-2017) 5 President’s Letter: Oscar Gershanik, MD, MDS President President 6 Feature Story: James Parkinson: The Many Facets of an Enlightened Man Oscar S. Gershanik, MD President-Elect 8 PAS Congress Christopher Goetz, MD 10 Society Announcements Secretary Claudia Trenkwalder, MD 14 Asian and Oceanian Section: Nobutaka Hattori, MD, PhD, MDS-AOS Chair Secretary-Elect 15 European Section: Joaquim Ferreira, MD, PhD, MDS-ES Chair Susan Fox, MRCP(UK), PhD 21 Pan American Section: Francisco Cardoso, MD, PhD, FAAN, MDS-PAS Chair Treasurer David John Burn, MD, FRCP Treasurer-Elect Victor Fung, MBBS, PhD, FRACP Past-President Matthew B. Stern, MD INTERNATIONAL EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Paolo Barone, MD, PhD Daniela Berg, MD Bastiaan Bloem, MD, PhD Carlos Cosentino, MD Beom S. -

An Investigation Into the Graphic Innovations of Geologist Henry T

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Uncovering strata: an investigation into the graphic innovations of geologist Henry T. De la Beche Renee M. Clary Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Clary, Renee M., "Uncovering strata: an investigation into the graphic innovations of geologist Henry T. De la Beche" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 127. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/127 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. UNCOVERING STRATA: AN INVESTIGATION INTO THE GRAPHIC INNOVATIONS OF GEOLOGIST HENRY T. DE LA BECHE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Curriculum and Instruction by Renee M. Clary B.S., University of Southwestern Louisiana, 1983 M.S., University of Southwestern Louisiana, 1997 M.Ed., University of Southwestern Louisiana, 1998 May 2003 Copyright 2003 Renee M. Clary All rights reserved ii Acknowledgments Photographs of the archived documents held in the National Museum of Wales are provided by the museum, and are reproduced with permission. I send a sincere thank you to Mr. Tom Sharpe, Curator, who offered his time and assistance during the research trip to Wales.