The Rise and Fall of the Irish Franciscan Monasteries, And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bishop Brendan Leahy

th . World Day of Poor 19 November, 2017 No great economic success story possible as long as homelessness and other poverty crises deepen – Bishop Brendan Leahy Ireland cannot claim itself an economic success while it allows the neglect of its poor, Bishop of Limerick Brendan Leahy has stated in his letter to the people of the diocese to mark the first World Day of the Poor. The letter - read at Masses across the diocese for the official World Day of the Poor called by Pope Francis – says that with homelessness at an unprecedented state of crisis today in Ireland, it is almost unjust and unchristian to claim economic success. “Throughout the centuries we have great examples of outreach to the poor. The most outstanding example is that of Francis of Assisi, followed by many other holy men and women over the centuries. In Ireland we can think of great women such as Catherine McAuley and Nano Nagle. “Today the call to hear the cry of the poor reaches us. In our Diocese we are blessed to have the Limerick Social Services Council that responds in many ways. There are many other initiatives that reach out to the homeless, refugees, people in situations of marginalisation,” he wrote. “But none of us can leave it to be outsourced to others to do. Each of us has to do our part. Today many of us live a privileged life in the material sense compared to generations gone by, Today is Mission Sunday and the Holy Father invites all Catholics to contribute to a special needing pretty much nothing. -

Chapter XII SEMINARY

Chapter XII SEMINARY Pugin Hall LVWKHSULQFLSDO'LQLQJ5RRPDW6DLQW3DWULFN¶V&ROOHJH0D\QRRWK 383 Classpiece 2017 384 Ordination to the Priesthood Damien Nejad, Diocese of Raphoe Sunday, 11th December 2016, Cathedral of St. Eunan & St. Columba, Letterkenny, Co Donegal Celebrant: Most Reverend Philip Boyce, Bishop of Raphoe Billy Caulfield, Diocese of Ferns Sunday, 11th -XQH6W-DPHV¶&KXUFK+RUHVZRRG&DPSLOH&R Wexford Celebrant: Most Reverend Denis Brennan, Bishop of Ferns (YLQ2¶%ULHQ'LRFHVHRI&RUN 5RVV Saturday, 10th June 2017 Church of the Holy Cross, Mahon, Cork Celebrant: Most Reverend John Buckley, Bishop of Cork & Ross Barry Matthews, Diocese of Armagh Sunday, June 18th6W3DWULFN¶V&KXUFK'XQGDON&R/RXWK Celebrant: His Grace Most Reverend Eamon Martin DD, Archbishop of Armagh David Vard, Diocese of Kildare & Leighlin Sunday, 25th -XQH6W&RQOHWK¶V3DULVK&KXUFK1HZEULGJH&R Kildare Celebrant: Most Reverend Denis Nulty, Bishop of Kildare & Leighlin Manuelito Milo, Diocese of Down & Connor Sunday, 25th -XQH6W3HWHU¶V&DWKHGUDO%HOIDVW&R$QWULP Celebrant: Most Reverend Noel Treanor, Bishop of Down & Connor John Magner, Diocese of Cloyne Sunday, 25th -XQH6W&ROPDQ¶V&DWKHGUDO&REK&R&RUN Celebrant: Most Reverend William Crean, Bishop of Cloyne. Declan Lohan, Diocese of Galway, Kilmacduagh & Kilfenora Sunday, 23rd July 2017, Church of the Immaculate Conception, Oranmore, Co Galway Celebrant: Most Reverend Brendan Kelly, Bishop of Achonry 385 Ordination to Diaconate College Chapel Sunday, 28th May 2017 by Most Reverend Michael Neary, Archbishop of Tuam Kevin Connolly, -

Project Gutenberg's a Popular History of Ireland V2, by Thomas D'arcy Mcgee #2 in Our Series by Thomas D'arcy Mcgee

Project Gutenberg's A Popular History of Ireland V2, by Thomas D'Arcy McGee #2 in our series by Thomas D'Arcy McGee Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: A Popular History of Ireland V2 From the earliest period to the emancipation of the Catholics Author: Thomas D'Arcy McGee Release Date: October, 2004 [EBook #6633] [Yes, we are more than one year ahead of schedule] [This file was first posted on January 6, 2003] Edition: 10 Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A POPULAR HISTORY OF IRELAND *** This etext was produced by Gardner Buchanan with help from Charles Aldarondo and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team. A Popular History of Ireland: from the Earliest Period to the Emancipation of the Catholics by Thomas D'Arcy McGee In Two Volumes Volume II CONTENTS--VOL. -

Cliffe / Vigors Estate 1096

Private Sources at the National Archives Cliffe / Vigors Estate 1096 1 ACCESSION NO. 1096 DESCRIPTION Family and Estate papers of the Cliffe / Vigors families, Burgage, Old Leighlin, Co. Carlow. 17th–20th centuries DATE OF ACCESSION 16 March 1979 ACCESS Open 2 1096 Cliffe / Vigors Family Papers 1 Ecclesiastical 1678–1866 2 Estate 1702–1902 3 Household 1735–1887 4 Leases 1673–1858 5 Legal 1720–1893 6 Photographs c.1862–c.1875 7 Testamentary 1705–1888 8 John Cliffe 1729–1830 9 Robert Corbet 1779–1792 10 Dyneley Family 1846–1932 11 Rev. Edward Vigors (1747–97) 1787–1799 12 Edward Vigors (1878–1945) 1878–1930 13 John Cliffe Vigors (1814–81) 1838–1880 14 Nicholas Aylward Vigors (1785–1840) 1800–1855 15 Rev. Thomas M. Vigors (1775–1850) 1793–1851 16 Thomas M.C. Vigors (1853–1908) 1771–1890 17 Cliffe family 1722–1862 18 Vigors family 1723–1892 19 Miscellaneous 1611–1920 3 1096 Cliffe / Vigors Family Papers The documents in this collection fall into neat groups. By far the largest section is that devoted to the legal work of Bartholomew Cliffe, Exchequer Attorney, who resided at New Ross. Many members of the Cliffe family were sovereigns and recorders of New Ross (Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, vol. ix, 1889, 312–17.) Besides intermarrying with their cousins, the Vigors, the Cliffe family married members of the Leigh and Tottenham families, these were also prominent in New Ross life (Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland), [op. cit.]. Col Philip Doyne Vigors (1825–1903) was a Vice President of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. -

Struck Off 2019 International Business Companies Registry of Belize

International Business Companies Registry of Belize Struck Off 2019 IBC Number IBC Name 404 Management Services Limited 660 Central American Marketing Associates Inc. 713 Morimor Holding Ltd. 1,834 Diamond Investments Ltd. 1,936 The Weston Bird Trust, Inc. 2,220 Roma Intercambio S.A. 2,445 Belize.Com Ltd. 2,447 Pishon Trust Management Limited 2,628 B.F.D. Limited 3,371 Bartin Management Corp. 3,413 Loury Investment S.A. 3,594 Bordes Investments Corp. 3,826 Professional Management Ltd. 4,049 Vernon Management Corp. 4,770 Greenfield Group Limited 5,261 International Fitness Federation Inc. 5,474 Efl Inc. 6,266 Maxwinn Co., Ltd. 6,293 Zalls Enterprises Inc. 6,373 Prosperous Consultants Ltd. 6,423 Queensway Trading Corporation 6,637 Sun King International Limited 7,052 Transcom International Inc. 7,137 Universal Shipping Services Ltd. 7,385 Donnybrook Company Limited 7,562 Nabos Overseas Inc. 7,604 Spartan Management Limited 7,763 Victory Co., Ltd. 7,925 The Marginal Ltd. 8,120 Auspice International Ltd. 8,178 Aremac Co., Ltd. 8,218 Talents Consolidated, Inc. 8,251 Sanlin Enterprises Ltd. 8,366 New World Consultants Limited 8,519 P. Leasing Corporation Limited 8,825 Amazing Energy Industrial Co., Ltd. 9,444 Munogenics, Inc. 9,580 Fortrose Marketing Inc. 9,711 Ppe Industrial Corp. 10,741 Worldwide Telecom Holdings, Inc. 10,785 Castle Group Management Ltd. 10,874 Jeng Well Int'L Co., Ltd. 11,492 Atlax Ventures Limited 11,992 Killan Enterprises Inc. 12,685 Crosten Marketing Ltd. 12,775 Adeward Holding S.A. 12,801 Induha Industrie-Service S.A. -

2004-Final-Program.Pdf

2004 Hawaii International Conference on Arts and Humanities Honolulu, Hawaii Welcome to the Second Annual Hawaii International Conference on Arts & Humanities Aloha! We welcome you to the Second Annual Hawaii International Conference on Arts & Humanities. This event offers a rare opportunity for academics, artists, performers and other professionals from around the world to share their broad array of perspectives. True to its primary goal, this conference provides those with cross-disciplinary interests related to arts and humanities to meet and interact with others inside and outside their own discipline. The international attendees to this conference bring a variety of viewpoints shaped by different cultures, languages, geography and politics. This diversity is also captured in the Hawaii International Conference’s unique cross-disciplinary approach. The resulting interaction energizes research as well as vocation. With Waikiki Beach, Diamond Head and the vast South Pacific as the backdrop, this venue is an important dimension of this conference. For centuries a stopping place of explorers, Hawaii has historically been enriched by the blend of ideas that have crossed our shores. The Hawaii International Conference on Arts & Humanities continues this tradition in the nurturing spirit of Aloha. Along with its ideal weather and striking beauty, the Hawaiian Islands provide natural elements to inspire learning and dialogue. The 2003 conference was a great success. We hosted more than 900 participants representing more than 40 countries. Thank you for joining the 2004 Hawaii International Conference on Arts & Humanities! Planning Committee Members Dr. William Pearman Dr. David Alethea Dr. Terry Gregson Dr. David Yang The 2005 Hawaii International Conference on Arts and Humanities is scheduled for January 13 – 16, 2005. -

Representative Church Body Library, Dublin C.2 Muniments of St

Representative Church Body Library, Dublin C.2 Muniments of St Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin 13th-20th cent. Transferred from St Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin, 1995-2002, 2012 GENERAL ARRANGEMENT C2.1. Volumes C2.2. Deeds C2.3. Maps C2.4. Plans and Drawings C2.5. Loose Papers C2.6. Photographs C.2.7. Printed Material C.2.8. Seals C.2.9. Music 2 1. VOLUMES 1.1 Dignitas Decani Parchment register containing copies of deeds and related documents, c.1190- 1555, early 16th cent., with additions, 1300-1640, by the Revd John Lyon in the 18th cent. [Printed as N.B. White (ed) The Dignitas Decani of St Patrick's cathedral, Dublin (Dublin 1957)]. 1.2 Copy of the Dignitas Decani An early 18th cent. copy on parchment. 1.3 Chapter Act Books 1. 1643-1649 (table of contents in hand of John Lyon) 2. 1660-1670 3. 1670-1677 [This is a copy. The original is Trinity College, Dublin MS 555] 4. 1678-1690 5. 1678-1713 6. 1678-1713 (index) 7. 1690-1719 8. 1720-1763 (table of contents) 9. 1764-1792 (table of contents) 10. 1793-1819 (table of contents) 11. 1819-1836 (table of contents) 12. 1836-1860 (table of contents) 13. 1861-1982 1.4 Rough Chapter Act Books 1. 1783-1793 2. 1793-1812 3. 1814-1819 4. 1819-1825 5. 1825-1831 6. 1831-1842 7. 1842-1853 8. 1853-1866 9. 1884-1888 1.5 Board Minute Books 1. 1872-1892 2. 1892-1916 3. 1916-1932 4. 1932-1957 5. -

TIGERSHARK Magazine

TIGERSHARK Magazine Issue Seven – Summer 2015 – Exploration Tigershark Magazine Contents Issue Seven – Summer 2015 Fiction Shut Up and Listen Exploration Gary Hewitt 4 The Call of the Siren Editorial Julio Toro San Martin 5 Join us as we set forth in search of new The Pyramid of Light and uncharted realms. As you may DJ Tyrer 9 notice, there was substantially more Why Explorers Are Bastards interest in exploring this and other Neil K. Henderson 11 worlds through the medium of poetry than in the form of prose, perhaps Troubles because it allows the mind to drift away Mitchell Grabois 14 to visit strange new vistas. The Grail of Derwandir Best, DS Davidson DS Davidson 15 On Passing Through... Dave Fragments 21 Poetry © Tigershark Publishing 2015 villa All rights reserved. Christopher Mulrooney 2 Authors retain the rights to their individual work. Under Waves & Radar AJ Huffman 2 Editor and Layout: DS Davidson Tranquility Assistant Editor: David Leverton AJ Huffman 3 Legend Next Issue's Theme: The Sea Neil K. Henderson 4 continues villa Under Waves and Radar By Christopher Mulrooney By AJ Huffman the sun over the hills Great white. leaves the lakeshore in shadow Ocean terror. still the trumpets of yellow Stalking surfers and seals. across the azure surface Unseen until dorsal fin breaks beckon to the boats Surface. Poetry (cont.) The Expunged Explorers A Crusader's Secret Heart Frederick J. Mayer 14 Donna Salisbury 4 It's All The Same Exploring the Path of Flawed Jewels Ian Dunlavy 20 Frederick J. Mayer 7 Dreamscapes Exploration Donna Salisbury 25 Aeronwy Dafies 8 From Anger This Anger The Lamp April Salzano 25 DS Davidson 11 The Burning in the Urn Haiku Robin Wyatt Dunn 26 Denny E. -

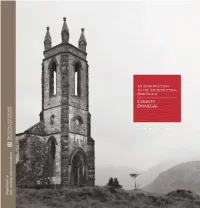

AN INTRODUCTION to the ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY DONEGAL

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY DONEGAL AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE of COUNTY DONEGAL COUNTY DONEGAL Mount Errigal viewed from Dunlewey. Foreword County Donegal has a rich architectural seventeenth-century Plantation of Ulster that heritage that covers a wide range of structures became a model of town planning throughout from country houses, churches and public the north of Ireland. Donegal’s legacy of buildings to vernacular houses and farm religious buildings is also of particular buildings. While impressive buildings are significance, which ranges from numerous readily appreciated for their architectural and early ecclesiastical sites, such as the important historical value, more modest structures are place of pilgrimage at Lough Derg, to the often overlooked and potentially lost without striking modern churches designed by Liam record. In the course of making the National McCormick. Inventory of Architectural Heritage (NIAH) The NIAH survey was carried out in phases survey of County Donegal, a large variety of between 2008 and 2011 and includes more building types has been identified and than 3,000 individual structures. The purpose recorded. In rural areas these include structures of the survey is to identify a representative as diverse as bridges, mills, thatched houses, selection of the architectural heritage of barns and outbuildings, gate piers and water Donegal, of which this Introduction highlights pumps; while in towns there are houses, only a small portion. The Inventory should not shopfronts and street furniture. be regarded as exhaustive and, over time, other A maritime county, Donegal also has a rich buildings and structures of merit may come to built heritage relating to the coast: piers, light. -

Carlow College

- . - · 1 ~. .. { ~l natp C u l,•< J 1 Journal of the Old Carlow Society 1992/1993 lrisleabhar Chumann Seanda Chatharlocha £1 ' ! SERVING THE CHURCH FOR 200 YEARS ! £'~,~~~~::~ai:~:,~ ---~~'-~:~~~ic~~~"'- -· =-~ : -_- _ ~--~~~- _-=:-- ·.. ~. SPONSORS ROYAL HOTEL- 9-13 DUBLIN STREET ~ P,•«•11.il H,,rd ,,,- Qua/in- O'NEILL & CO. ACCOUNTANTS _;, R-.. -~ ~ 'I?!~ I.-: _,;,r.',". ~ h,i14 t. t'r" rhr,•c Con(crcncc Roonts. TRAYNOR HOUSE, COLLEGE STREET, CARLOW U • • i.h,r,;:, F:..n~ r;,,n_,. f)lfmt·r DL1nccs. PT'i,·atc Parties. Phone:0503/41260 F."-.l S,:r.cJ .-\II Da,. Phone 0503/31621. t:D. HAUGHNEY & SON, LTD. Jewellers, ·n~I, Fashion Boutique, Fuel Merchant. Authorised Ergas Stockist ·~ff 62-63 DUBLIN ST., CARLOW POLLERTON ROAD, CARLOW. Phone 0503/31367 OF CARLOW Phone:0503/31346 CIGAR DIVAN TULL Y'S TRAVEL AGENCY Newsagent, Confectioner, Tobacconist, etc. TULLOW STREET, CARLOW DUBLIN STREET, CARLOW Phone:0503/31257 Bring your friends to a musical evening in Carlow's unique GACH RATH AR CARLOVIANA Music Lounge each Saturday and Sunday. Phone: 0503/27159. ST. MARY'S ACADEMY, SMYTHS of NEWTOWN CARLOW SINCE 1815 DEERPARK SERVICE STATION MICHAEL DOYLE Builders Providers, General Hardware Tyre Service and Accessories 'THE SHAMROCK", 71 TULLOW STREET, CARLOW DUBLIN ROAD, CARLOW. Phone 0503/31414 Phone:0503/31847 THOMAS F. KEHOE SEVEN OAKS HOTEL Specialist Livestock Auctioneer and Valuer, Far, Sales and Lettings,. Property and Est e Agent. Dinner Dances * Wedding Receptions * Private Parties Agent for the Irish Civil Ser- ce Building Society. Conferences * Luxury Lounge 57 DUBLIN STREET, CARLOW. Telephone 0503/31678, 31963. -

The Irish Catholic Episcopal Corps, 1657 – 1829: a Prosopographical Analysis

THE IRISH CATHOLIC EPISCOPAL CORPS, 1657 – 1829: A PROSOPOGRAPHICAL ANALYSIS VOLUME 1 OF 2 BY ERIC A. DERR THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PHD DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERISTY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH SUPERVISOR OF RESEARCH: DR. THOMAS O’CONNOR NOVEMBER 2013 Abstract This study explores, reconstructs and evaluates the social, political, educational and economic worlds of the Irish Catholic episcopal corps appointed between 1657 and 1829 by creating a prosopographical profile of this episcopal cohort. The central aim of this study is to reconstruct the profile of this episcopate to serve as a context to evaluate the ‘achievements’ of the four episcopal generations that emerged: 1657-1684; 1685- 1766; 1767-1800 and 1801-1829. The first generation of Irish bishops were largely influenced by the complex political and religious situation of Ireland following the Cromwellian wars and Interregnum. This episcopal cohort sought greater engagement with the restored Stuart Court while at the same time solidified their links with continental agencies. With the accession of James II (1685), a new generation of bishops emerged characterised by their loyalty to the Stuart Court and, following his exile and the enactment of new penal legislation, their ability to endure political and economic marginalisation. Through the creation of a prosopographical database, this study has nuanced and reconstructed the historical profile of the Jacobite episcopal corps and has shown that the Irish episcopate under the penal regime was not only relatively well-organised but was well-engaged in reforming the Irish church, albeit with limited resources. By the mid-eighteenth century, the post-Jacobite generation (1767-1800) emerged and were characterised by their re-organisation of the Irish Church, most notably the establishment of a domestic seminary system and the setting up and manning of a national parochial system. -

Elizabeth I and Irish Rule: Causations For

ELIZABETH I AND IRISH RULE: CAUSATIONS FOR CONTINUED SETTLEMENT ON ENGLAND’S FIRST COLONY: 1558 - 1603 By KATIE ELIZABETH SKELTON Bachelor of Arts in History Oklahoma State University Stillwater, Oklahoma 2009 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS May, 2012 ELIZABETH I AND IRISH RULE: CAUSATIONS FOR CONTINUED SETTLEMENT ON ENGLAND’S FIRST COLONY: 1558 - 1603 Thesis Approved: Dr. Jason Lavery Thesis Adviser Dr. Kristen Burkholder Dr. L.G. Moses Dr. Sheryl A. Tucker Dean of the Graduate College ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................... 1 II. ENGLISH RULE OF IRELAND ...................................................... 17 III. ENGLAND’S ECONOMIC RELATIONSHIP WITH IRELAND ...................... 35 IV. ENGLISH ETHNIC BIAS AGAINST THE IRISH ................................... 45 V. ENGLISH FOREIGN POLICY & IRELAND ......................................... 63 VI. CONCLUSION ...................................................................... 90 BIBLIOGRAPHY ........................................................................ 94 iii LIST OF MAPS Map Page The Island of Ireland, 1450 ......................................................... 22 Plantations in Ireland, 1550 – 1610................................................ 72 Europe, 1648 ......................................................................... 75 iv LIST OF TABLES Table Page