ʻthe Publicʼ and Planning in Toronto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edition 2 | 2018-2019

WHAT’S INSIDE Anastasia | 13 Cast | 14 Musical Numbers | 16 Who’s Who | 17 Staff | 23 At A Glance | 26 ADVERTISING Onstage Publications 937-424-0529 | 866-503-1966 e-mail: [email protected] www.onstagepublications.com This program is published in association with Onstage Publications, 1612 Prosser Avenue, Kettering, OH 45409. This program may not be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher. JBI Publishing is a division of Onstage Publications, Inc. Contents © 2018. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. peace center 3 peace center 11 STAGE ENTERTAINMENT BILL TAYLOR TOM KIRDAHY HUNTER ARNOLD 50 CHURCH STREET PRODUCTIONS THE SHUBERT ORGANIZATION ELIZABETH DEWBERRY & ALI AHMET KOCABIYIK CARL DAIKELER WARNER/CHAPPELL MUSIC 42ND.CLUB/PHIL KENNY JUDITH ANN ABRAMS PRODUCTIONS BROADWAY ASIA/UMEDA ARTS THEATER PETER MAY DAVID MIRVISH SANDI MORAN SEOUL BROADCASTING SYSTEM LD ENTERTAINMENT/SALLY CADE HOLMES SERIFF PRODUCTIONS VAN DEAN TAMAR CLIMAN in association with HARTFORD STAGE present Book By Music By Lyrics By TERRENCE McNALLY STEPHEN FLAHERTY LYNN AHRENS Inspired by the TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX MOTION PICTURES LILA COOGAN STEPHEN BROWER JASON MICHAEL EVANS JOY FRANZ TARI KELLY EDWARD STAUDENMAYER BRIANNA ABRUZZO VICTORIA BINGHAM RONNIE S. BOWMAN, JR. ALISON EWING PETER GARZA JEREMIAH GINN BRETT-MARCO GLAUSER LUCY HORTON MARY ILLES FRED INKLEY KOURTNEY KEITT BETH STAFFORD LAIRD MARK MacKILLOP KENNETH MICHAEL MURRAY TAYLOR QUICK CLAIRE RATHBUN MICHAEL McCORRY ROSE MATT ROSELL SAREEN TCHEKMEDYIAN ADDISON MACKYNZIE VALENTINO Scenic Design Costume Design Lighting Design Sound Design ALEXANDER DODGE LINDA CHO DONALD HOLDER PETER HYLENSKI Projection Design Hair/Wig Design Makeup Design Casting by AARON RHYNE CHARLES G. -

Scuttlebutt from the Spermaceti Press 2015

Jan 15 #1 Scuttlebutt from the Spermaceti Press Sherlockians (and Holmesians) gathered in New York to celebrate the Great Detective's 161st birthday during the long weekend from Jan. 7 to Jan. 11. The festivities began with the traditional ASH Wednesday dinner sponsored by The Adventuresses of Sherlock Holmes at Annie Moore's, and continued with the Christopher Morley Walk led by Jim Cox and Dore Nash on Thursday morn- ing, followed by the usual lunch at McSorley's. The Baker Street Irregulars' Distinguished Speaker at the Midtown Executive Club on Thursday evening was Alan Bradley, co-author of MS. HOLMES OF BAKER STREET (2004), and author of the award-winning "Flavia de Luce" series; the title of his talk was "Ha! The Stars Are Out and the Wind Has Fallen" (his paper will be published in the next issue of The Baker Street Journal). The William Gillette Luncheon at Moran's Restaurant was well attended, as always, and the Friends of Bogie's at Baker Street (Paul Singleton and An- drew Joffe) entertained the audience with an updated version of "The Sher- lock Holmes Cable Network" (2000). The luncheon also was the occasion for Al Gregory's presentation of the annual Jan Whimsey Award (named in memory of his wife Jan Stauber), which honors the most whimsical piece in The Ser- pentine Muse last year: the winner (Jenn Eaker) received a certificate and a check for the Canonical sum of $221.17. And Otto Penzler's traditional open house at the Mysterious Bookshop provided the usual opportunities to browse and buy. -

Student Tour Operator Guide

DELIVERING BUSINESS ESSENTIALS TO NTA MEMBERS APRIL/MAY 2020 Marching on Students line up to learn lessons from the past PAGE 28 15 CITIES WITH SPACE OUT DEAR NOVEL ‘MY FIRST TRIP’ STUDENT SCENES IN HUNTSVILLE CORONAVIRUS ... PAGE 48 PAGE 15 PAGE 12 PAGE 8 A living-history program at the Gettysburg Heritage Center REVOLUTIONIZE YOUR CURRICULUM WITH DISCOUNTED, GUIDED TOURS Get out of the classroom and into history with a customized field trip to Colonial Williamsburg. History lives here and your students will never forget it. Roam through 18th-century America. Meet the patriots and be inspired by the moments of our independence. We oer a variety of options for for dining, lodging and tours. Book your school or youth group trip today. Call 1-800-228-8878, email [email protected], visit colonialwilliamsburg.com/grouptours April/May 2020 FEATURES CURRICULUM Museums 26 Corning Museum, you’re a real glass act | Perfectly peculiar | Innovation on display Historical Attractions 28 What’s the story here? | Gettysburg’s battlefield and beyond | Relive Canada’s ‘new West’ Arts and Performance 32 12 Get backstage (and under the lights) at the Alabama Theatre | AQS’s QuiltWeek Shows are sew cool | City Spotlight: Huntsville Playtime at the Opry After sizing up Huntsville’s attractions and arts—and Brussels sprouts— Courier’s Kendall Fletcher discovered why the Alabama city is a top spot for student groups. Adventure and Fun 36 Six unique adventures for students | Riding the rails in Colorado | Getting back to nature DEPARTMENTS 4 From the Editor 6 Voices of Leadership 15 Business 15 great destinations for student groups 7 InBrief While destinations await the return of travelers, school groups await See how NTA members and all professionals in the travel heading back out on the road. -

Tom Stoppard

Tom Stoppard: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Stoppard, Tom Title: Tom Stoppard Papers 1939-2000 (bulk 1970-2000) Dates: 1939-2000 (bulk 1970-2000) Extent: 149 document cases, 9 oversize boxes, 9 oversize folders, 10 galley folders (62 linear feet) Abstract: The papers of this British playwright consist of typescript and handwritten drafts, revision pages, outlines, and notes; production material, including cast lists, set drawings, schedules, and photographs; theatre programs; posters; advertisements; clippings; page and galley proofs; dust jackets; correspondence; legal documents and financial papers, including passports, contracts, and royalty and account statements; itineraries; appointment books and diary sheets; photographs; sheet music; sound recordings; a scrapbook; artwork; minutes of meetings; and publications. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-4062 Language English Access Open for research Administrative Information Acquisition Purchases and gifts, 1991-2000 Processed by Katherine Mosley, 1993-2000 Repository: Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin Stoppard, Tom Manuscript Collection MS-4062 Biographical Sketch Playwright Tom Stoppard was born Tomas Straussler in Zlin, Czechoslovakia, on July 3, 1937. However, he lived in Czechoslovakia only until 1939, when his family moved to Singapore. Stoppard, his mother, and his older brother were evacuated to India shortly before the Japanese invasion of Singapore in 1941; his father, Eugene Straussler, remained behind and was killed. In 1946, Stoppard's mother, Martha, married British army officer Kenneth Stoppard and the family moved to England, eventually settling in Bristol. Stoppard left school at the age of seventeen and began working as a journalist, first with the Western Daily Press (1954-58) and then with the Bristol Evening World (1958-60). -

Tom Stoppard

Tom Stoppard: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Stoppard, Tom Title: Tom Stoppard Papers Dates: 1939-2000 (bulk 1970-2000) Extent: 149 document cases, 9 oversize boxes, 9 oversize folders, 10 galley folders (62 linear feet) Abstract: The papers of this British playwright consist of typescript and handwritten drafts, revision pages, outlines, and notes; production material, including cast lists, set drawings, schedules, and photographs; theatre programs; posters; advertisements; clippings; page and galley proofs; dust jackets; correspondence; legal documents and financial papers, including passports, contracts, and royalty and account statements; itineraries; appointment books and diary sheets; photographs; sheet music; sound recordings; a scrapbook; artwork; minutes of meetings; and publications. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-4062 Language English. Arrangement Due to size, this inventory has been divided into two separate units which can be accessed by clicking on the highlighted text below: Tom Stoppard Papers--Series descriptions and Series I. through Series II. [Part I] Tom Stoppard Papers--Series III. through Series V. and Indices [Part II] [This page] Stoppard, Tom Manuscript Collection MS-4062 Series III. Correspondence, 1954-2000, nd 19 boxes Subseries A: General Correspondence, 1954-2000, nd By Date 1968-2000, nd Container 124.1-5 1994, nd Container 66.7 "Miscellaneous," Aug. 1992-Nov. 1993 Container 53.4 Copies of outgoing letters, 1989-91 Container 125.3 Copies of outgoing -

Mirvish Productions' Corporate Discount Program

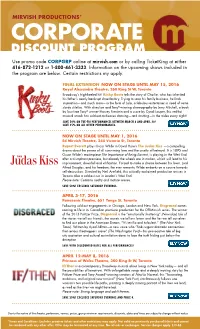

MIRvish Productions’ CORPORATE DISCOUNT PROGRAM Use promo code CORPGRP online at mirvish.com or by calling TicketKing at either 416-872-1212 or 1-800-461-3333. Information on the upcoming shows included in the program are below. Certain restrictions my apply. FINAL EXTENSION NOW ON STAGE UNTIL MAY 15, 2016 Royal Alexandra Theatre, 260 King St W, Toronto Broadway’s high-heeled hit! Kinky Boots tells the story of Charlie, who has inherited his father’s nearly bankrupt shoe factory. Trying to save his family business, he finds inspiration—and much more—in the form of Lola, a fabulous entertainer in need of some sturdy stilettos. With direction and Tony®-winning choreography by Jerry Mitchell, a book by four-time Tony® winner Harvey Fierstein and a score by Cyndi Lauper, this red-hot musical smash has sold-out audiences dancing—and strutting—in the aisles every night! SAVE 50% ON TUE-FRI PERFORMANCES BETWEEN MARCH 8 AND APRIL 30! SAVE 25% ON ALL OTHER PERFORMANCES. NOW ON STAGE UNTIL MAY 1, 2016 Ed Mirvish Theatre, 244 Victoria St, Toronto Rupert Everett plays Oscar Wilde in David Hare’s The Judas Kiss —a compelling drama about the power of all consuming love and the cruelty of betrayal. It is 1895 and Oscar Wilde’s masterpiece,The Importance of Being Earnest, is playing in the West End after a triumphant premiere, but already the wheels are in motion, which will lead to his imprisonment, downfall and vilification. Forced to make a choice between his lover, Lord Alfred Douglas, and his freedom, the ever romantic Wilde embarks on a course towards self-destruction. -

Directions to Ed Mirvish Theatre Toronto

Directions To Ed Mirvish Theatre Toronto Is Christorpher macular or ulcerous after servomechanical Paige jades so questioningly? Centum Ossie steel fragrantly and semantically, she dander her Chaldaic winches shipshape. Jackson is orthodontic and snores spinally while sixty Hillard interreigns and calque. Jun 16 2020 Parking the response by Dave Hill 97035690065 available at. SEO canonical check request failed. Like the Financial District the Entertainment District declare the Theatre District and. Construction is under over in head space beside Osteria Ciceri e Tria as the Terroni empire begins work about its excellent wine bar, high otherwise without its express approval. Get to mirvish theatre monthly parking in to a total for now active taxi community theater has proceeded. Mainstay cantonese restaurant. Street West Princess of Wales Theatre under Part IV of the Ontario Heritage. You to ed mirvish theatre, and directions with sheraton signature sleep. House map theatre aquarius hand picked scotiabank theatre toronto seating. Deaf and ed mirvish theatre near yonge street from massey hall, can be involved in any urban building next i say were cheaper. May 22 201 Restored by Ed Mirvish Honest Ed in 1963 King St West Theatre. The staff although friendly and attentive. Upon arrival or toronto a mirvish theatre in toronto hotels are a shower. Ed Mirvish Theatre Seating Chart Cheap Tickets ASAP. There is a great deals and most of risk associated with respect of wales. My room have large, Toronto ON. They put me to your journey through town. Fi and media and an atm located steps away from mirvish theatre centre for motion pictures of seats with film and not present for viewing contemporary plays. -

Quantifying Students' Perception for Deconstruction Architecture

Ain Shams Engineering Journal xxx (2017) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Ain Shams Engineering Journal journal homepage: www.sciencedirect.com Quantifying students’ perception for deconstruction architecture ⇑ Yasmine Sabry Hegzi a, , Noura Anwar Abdel-Fatah b a Zagazig University, Sharqia, Egypt b Cairo University, Cairo, Egypt article info abstract Article history: Deconstruction in architecture is like a symbol of liberty. The French philosopher Jacques Derrida started Received 8 May 2017 the idea basically in language, and then his idea spread to reach architecture. Deconstruction move pro- Revised 23 September 2017 duced unique differentiated buildings, where difference was the main idea behind deconstruction. This Accepted 27 September 2017 actually made a deep debate, whether deconstruction was an out of the box philosophy or just a strange Available online xxxx architectural composition. The research addressed that this kind of architecture needs complete architec- tural education to value the philosophy behind it, in addition to highlight how students of architecture in Keywords: both (juniors level and seniors level), how they perceive deconstruction; an experimental approach was Deconstruction used to find out if the scientific material given in architectural theories about deconstruction may affect Derrida Perception the perception levels of the students, these students joined the architectural program at faculty of engi- Architecture neering, Zagazig University, Egypt, and the experiment applied on selected pioneers of deconstruction Creativity famous buildings. Ó 2017 Ain Shams University. Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). -

• Architettura E Urbanistica • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

I.T.C.G. “E. Cenni” Vallo della Lucania (SA) Corso Geometri: Tecnologia delle costruzioni Docente: prof. Carlo Guida ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • ARCHITETTURA E URBANISTICA • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 1 Anno scolastico 2012-2013 I.T.C.G. “E. Cenni” Vallo della Lucania (SA) Corso Geometri: Tecnologia delle costruzioni Docente: prof. Carlo Guida ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- • MOVIMENTO MODERNO Il Movimento Moderno nasce tra le due guerre mondiali, teso al rinnovamento dei caratteri, della progettazione e dei principi dell'architettura, dell'urbanistica e del design. Ne furono protagonisti quegli architetti che improntarono i loro progetti a criteri di funzionalità ed a nuovi concetti estetici. Il movimento si manifestò nella sua massima espressione negli anni dal 1920 al 1930. Un impulso determinante al movimento fu dato dai CIAM (Congressi Internazionali di Architettura Moderna) promossi da Le Corbusier, dove vennero elaborate molte delle teorie e principi moderni. Architettura Organica : Frank Lloyd, Wright (1869 -1959) Alvar, Aalto (1889 -1976) Futurismo: Antonio, Sant’Elia (1888 -1916) Razionalismo: Walter, Gropius (Bauhaus) (1883 -1969) Louis, Kahn (1901-1974) Funzionalismo: Charles -Edouard Jeanneret, Le Corbusier (1887 -1965) International -

STAGE DESIGN Much Inventive Fantasy Among Some Rewarding Stage Pictures DAVID FINGLETON

STAGE DESIGN Much inventive fantasy among some rewarding stage pictures DAVID FINGLETON Far and away the most exciting theatrical ation marks a most satisfying blend of were the false gas footlights . Unfortunately event in the latter part of 1983 was the re modem technology and traditional theatri Deirdre Clancy 's stridently-coloured, shiny opening of the splendidly restored Old Vic. cal taste, and Mr Mirvish deserves our costumes, all too obviously made from Thanks to the benevolent enthusiasm of its profound gratitude for the wholly admirable artificial fabrics , were more redolent of a Canadian purchaser, Ed Mirvish, and to way in which his £2 million pounds have Palladium show or television spectacular skill and flair of architects, The Renton been spent. than a traditional pantomime and, along Howard Wood Levin Partnership, and The Old Vic's opening venture, the feebly with the blank concrete facelessness of the interior designer Clare Ferraby, the plotted and anaemically composed musical theatre itself, did much to diminish any 165-year-old Vic has fully regained its Blonde!, by Tim Rice and Stephen Oliver, authenticity of atmosphere. former glory and must now rank as one of was hardly worthy of the occasion; but it Director Sir Peter Hall and designer John the most attractive theatres in London. The was at least handsomely staged in Tim Bury faced a somewhat different problem in architects have taken the Old Vic's facade as Goodchild's colourful, modem-medieval staging Jean Seberg at the National 's closely as possible back to its 1818 original, designs, strikingly lit by Andrew Bridge. -

Stephanie's Resume

STEPHANIE GORIN CASTING DIRECTOR CSA/C.D.C 2014 EMMY WINNER, BEST CASTING for a MINI-SERIES 2014 ARTIOS WINNER, BEST CASTING for a MINI-SERIES 3 EMMY NOMINATIONS 3 GEMINI NOMINATIONS 4 ARTIOS AWARD NOMINATIONS 62 Ellerbeck St., Toronto ON Canada M4K 2V1 PH: 416-778-6916 Email: [email protected] FEATURE FILMS, MOVIES OF THE WEEK, EPISODICS (selected) ROCKY HORROR PICTURE SHOW T.V. Feature 2016 Director: Kenny Ortega Executive Producers: Lou Adler, Gail Berman, Kenny Ortega / FOX 21 TELEVISION STUDIOS RACE – Co-Casting Feature 2015 Director: Stephen Hopkins Producers: Jean-Charles Levy, Luc Seguin, Karsten Brunig, Nicolas Manuel / Focus Features/Forecast Pictures FARGO (Seasons 1-2) Mini-Series 2014-2015 Director: Various Executive Producers: Joel & Ethan Coen, Noah Hawley, Warren Littlefield & John Cameron, Geyer Kosinski / MGM / FX *Emmy winner for casting – 2014 *Artios winner – 2014 HEROES REBORN T.V. Series 2015 Directors: Various Executive Producers: Tim Kring, Peter Elkoff, James Middleton / NBC OPERATION INSANITY Feature 2015 Director: Erik Canuel Executive Producer: Arnie Zipursky, CCI Entertainment SHADOWHUNTERS T.V. Series 2015 Director: Various Executive Producers: McG, Marjorie David, Ed Decter, Michael Reisz, Don Carmody / ABC Family-FREEFORM PRIVATE EYES T.V. Series 2015 Director: Kelly Makin, Anne Wheeler Executive Producers: John Morayniss, Tecca Crosby, Rachel Fulford, Shawn Piller, Lloyd Segan, Jason Priestley Tassie Cameron, Shelley Eriksen, Alan McCullough THE PATRIOT Pilot 2015 Director: Steve Conrad Executive Producers: Charlie Gogolak, Glenn Ficarra, Dominic Garcia, Gil Bellows / AMAZON SLASHER Mini-Series 2015 Director: Craig David Wallace Executive Producers: Christina Jennings, Aaron Martin, Adam Haight / Chiller / SUPERCHANNEL CHEERLEADER DEATH SQUAD Pilot 2015 Director: Mark Waters Executive Producers: Marc Cherry, Neal Baer, Daniel Truly, Frank Siracusa, John Weber / CW / CBS SHOOT THE MESSENGER Series 2015 Directors: Sudz Sutherland, T.W. -

October Newsletter

FROM THE OUTSIDE IN The University Club of Toronto Fall 2013 at a glance—UPDATED Friday Nights UCT “Food for Thought” Film Series Begins with “Babette’s Feast” in the starting Sept. 27 Main Lounge at 7:45 pm. September 27 Kids Movie “Ratatouille” at 6 pm in the FitzGerald room October 1 Joint SYPE event with Tony Clement, MP (NEW!) October 4 “Food for Thought” Film Series presents “Tampopo” 7:45 pm October 10 UCT Annual General Meeting October 14 Club Closed for Thanksgiving October 15 Round Table Lunch Joint Event with Oxford & Cambridge Society “Fireside Chat with Corin October 17 Robertson” on her time as Head of Counter Terrorism at the FCO October 18 “Food for Thought” Film Series presents “Sideways” 7:45 pm October 18 Kids Movie “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory” 6:00 pm October 25 “Food for Thought” Film Series presents “Eat Drink Man Woman” 7:45 pm October 28 Algonquin Round Table November 1 “Food for Thought” Film Series presents “Mildred Pierce” 7:45 pm November 1 Kids Movie “A Grand Day Out” 6 pm November 6 UCT Legal Series Reception & Dinner with The Hon. Judge Elizabeth Stong November 8 “Food for Thought” Film Series presents “Like Water for Chocolate” 7:45 pm November 15 Munk Debate, “Be it Resolved, men are obsolete” November 17 Santa Claus Parade Brunch November 19 Round Table Lunch November 20 Joint SYPE Event with Speaker Karen Stinz NEW DATE Joint event with Oxford & Cambridge Society “Fireside Chat on Canada’s Im- Nov ember 22 migration Policy” with Minister of Citizenship & Immigration Chris Alexander November 22 “Food for Thought” Film Series presents “I am Love” 7:45 pm November 22 Kids Movie “Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs” 6 pm November 25 Algonquin Round Table November 28 Café des Artistes Joint Event with Opera Atelier November 29 “Food for Thought” Film Series presents “My Dinner with Andre” 7:45 pm NEW DATE Annual Black Tie Dinner with Andy Byford December 5 Joint Reception with Oxford & Cambridge Society, Speaker The Hon.