An Archaeological Resource Assessment of the Neolithic and Early Bronze Age in Derbyshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The University of Bradford Institutional Repository

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Bradford Scholars The University of Bradford Institutional Repository http://bradscholars.brad.ac.uk This work is made available online in accordance with publisher policies. Please refer to the repository record for this item and our Policy Document available from the repository home page for further information. To see the final version of this work please visit the publisher’s website. Where available access to the published online version may require a subscription. Author(s): Gibson, Alex M. Title: An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? Publication year: 2012 Book title: Enclosing the Neolithic : Recent studies in Britain and Ireland. Report No: BAR International Series 2440. Publisher: Archaeopress. Link to publisher’s site: http://www.archaeopress.com/archaeopressshop/public/defaultAll.asp?QuickSear ch=2440 Citation: Gibson, A. (2012). An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? In: Gibson, A. (ed.). Enclosing the Neolithic: Recent studies in Britain and Europe. Oxford: Archaeopress. BAR International Series 2440, pp. 1-20. Copyright statement: © Archaeopress and the individual authors 2012. An Introduction to the Study of Henges: Time for a Change? Alex Gibson Abstract This paper summarises 80 years of ‘henge’ studies. It considers the range of monuments originally considered henges and how more diverse sites became added to the original list. It examines the diversity of monuments considered to be henges, their origins, their associated monument types and their dates. Since the introduction of the term, archaeologists have often been uncomfortable with it. -

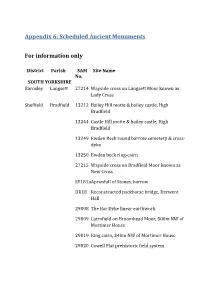

Appendix 6: Scheduled Ancient Monuments for Information Only

Appendix 6: Scheduled Ancient Monuments For information only District Parish SAM Site Name No. SOUTH YORKSHIRE Barnsley Langsett 27214 Wayside cross on Langsett Moor known as Lady Cross Sheffield Bradfield 13212 Bailey Hill motte & bailey castle, High Bradfield 13244 Castle Hill motte & bailey castle, High Bradfield 13249 Ewden Beck round barrow cemetery & cross- dyke 13250 Ewden beck ring-cairn 27215 Wayside cross on Bradfield Moor known as New Cross SY181a Apronfull of Stones, barrow DR18 Reconstructed packhorse bridge, Derwent Hall 29808 The Bar Dyke linear earthwork 29809 Cairnfield on Broomhead Moor, 500m NW of Mortimer House 29819 Ring cairn, 340m NW of Mortimer House 29820 Cowell Flat prehistoric field system 31236 Two cairns at Crow Chin Sheffield Sheffield 24985 Lead smelting site on Bole Hill, W of Bolehill Lodge SY438 Group of round barrows 29791 Carl Wark slight univallate hillfort 29797 Toad's Mouth prehistoric field system 29798 Cairn 380m SW of Burbage Bridge 29800 Winyard's Nick prehistoric field system 29801 Ring cairn, 500m NW of Burbage Bridge 29802 Cairns at Winyard's Nick 680m WSW of Carl Wark hillfort 29803 Cairn at Winyard's Nick 470m SE of Mitchell Field 29816 Two ring cairns at Ciceley Low, 500m ESE of Parson House Farm 31245 Stone circle on Ash Cabin Flat Enclosure on Oldfield Kirklees Meltham WY1205 Hill WEST YORKSHIRE WY1206 Enclosure on Royd Edge Bowl Macclesfield Lyme 22571 barrow Handley on summit of Spond's Hill CHESHIRE 22572 Bowl barrow 50m S of summit of Spond's Hill 22579 Bowl barrow W of path in Knightslow -

Report on a New Horizons Research Project. MAGNETOMETER

Report on a New Horizons Research Project. MAGNETOMETER SURVEYS OF PREHISTORIC STONE CIRCLES IN BRITAIN, 1986. by A. Jensine Andresen and Mark Bonchek of Princeton University. Copyright: A. Jensine Andresen, Mark Bonchek and the New Horizons Research Foundation. November 1986. CONTENTS. Introductory Note. Magnetic Surveying Project Report on Geomantic Resea England, June 16 - July 22, 1986. Selected Notes. Bibliography. 1. Introductory Note. This report deals with a piece of research falling within the group of enquiries comprised under the term "geomancy". which has come into use during the past twenty years or so to connote what could perhaps be called the as yet somewhat speculative study of various presumed subtle or occult properties of terrestrial landscapes and the earth beneath them. In earlier times the word "geomancy" was used rather differently in relation to divination or prophecy carried out by means of some aspect of the earth, but nowadays it refers to the study of what might be loosely called "earth mysteries". These include the ancient Chinese lore and practical art of Fengshui -- the correct placing of buildings with respect to the local conformation of hills and dales, the orientation of medieval churches, the setting of buildings and monuments along straight lines (i.e. the so-called ley lines or leys). These topics all aroused interest in the early decades of the present century. Similarly,since about 1900 interest in megalithic monuments throughout western Europe has steadily increased. This can be traced to a variety of causes, which include increased study and popularisation of anthropology, folklore and primitive religion (e.g. -

Rude Stone Monuments Chapt

RUDE STONE MONUMENTS IN ALL COUNTRIES; THEIR AGE AND USES. BY JAMES FERGUSSON, D. C. L., F. R. S, V.P.R.A.S., F.R.I.B.A., &c, WITH TWO HUNDRED AND THIRTY-FOUR ILLUSTRATIONS. LONDON: ,JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET. 1872. The right of Translation is reserved. PREFACE WHEN, in the year 1854, I was arranging the scheme for the ‘Handbook of Architecture,’ one chapter of about fifty pages was allotted to the Rude Stone Monuments then known. When, however, I came seriously to consult the authorities I had marked out, and to arrange my ideas preparatory to writing it, I found the whole subject in such a state of confusion and uncertainty as to be wholly unsuited for introduction into a work, the main object of which was to give a clear but succinct account of what was known and admitted with regard to the architectural styles of the world. Again, ten years afterwards, while engaged in re-writing this ‘Handbook’ as a History of Architecture,’ the same difficulties presented themselves. It is true that in the interval the Druids, with their Dracontia, had lost much of the hold they possessed on the mind of the public; but, to a great extent, they had been replaced by prehistoric myths, which, though free from their absurdity, were hardly less perplexing. The consequence was that then, as in the first instance, it would have been necessary to argue every point and defend every position. Nothing could be taken for granted, and no narrative was possible, the matter was, therefore, a second time allowed quietly to drop without being noticed. -

Reconstructing Palaeoenvironments of the White Peak Region of Derbyshire, Northern England

THE UNIVERSITY OF HULL Reconstructing Palaeoenvironments of the White Peak Region of Derbyshire, Northern England being a Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Hull by Simon John Kitcher MPhysGeog May 2014 Declaration I hereby declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own, except where otherwise stated, and that it has not been previously submitted in application for any other degree at any other educational institution in the United Kingdom or overseas. ii Abstract Sub-fossil pollen from Holocene tufa pool sediments is used to investigate middle – late Holocene environmental conditions in the White Peak region of the Derbyshire Peak District in northern England. The overall aim is to use pollen analysis to resolve the relative influence of climate and anthropogenic landscape disturbance on the cessation of tufa production at Lathkill Dale and Monsal Dale in the White Peak region of the Peak District using past vegetation cover as a proxy. Modern White Peak pollen – vegetation relationships are examined to aid semi- quantitative interpretation of sub-fossil pollen assemblages. Moss-polsters and vegetation surveys incorporating novel methodologies are used to produce new Relative Pollen Productivity Estimates (RPPE) for 6 tree taxa, and new association indices for 16 herb taxa. RPPE’s of Alnus, Fraxinus and Pinus were similar to those produced at other European sites; Betula values displaying similarity with other UK sites only. RPPE’s for Fagus and Corylus were significantly lower than at other European sites. Pollen taphonomy in woodland floor mosses in Derbyshire and East Yorkshire is investigated. -

The 1717 Guide Stoop on Longstone Edge. Is It Missing?

The 1717 Guide Stoop on Longstone Edge. Is it missing? Ann Hall with valuable assistance from Alan Jones Introduction When Alison Stuart was preparing to move out of her family home at Christmas Cottage in Little Longstone shortly after Michael's death in 2012, she asked Hillary Clarke and I to help with finding the most appropriate home for papers that he had collected during his historical research. As we worked through a lifetime's work on many topics of local interest we came upon a photocopy of a guide stoop. Hilary recognised it as the one from Longstone Edge and I became interested to find out more. This article is the result of my investigations. Some of my chief sources of information were from books which describe rambles through Derbyshire in a rather romantic manner in the first half of the nineteenth century. They were not intended to be full scientific records of features along the way but rather a description of interesting walks and fascinating items along the route. The record in the books is not always reliable but I have tried to extract as much sound information as I can. There are records of a guide stoop, dated 1717, on Longstone Edge since 1905. Some of the earlier information is quite detailed and this suggests that it really was in existence at Page 2 of 5 Guide Stoop on Longstone Edge the time of the recording. In more recent reports it is listed as missing. My recent research intended to find out if it really is lost for ever. -

Mercian 11 B Hunter.Indd

The Cressbrook Dale Lava and Litton Tuff, between Longstone and Hucklow Edges, Derbyshire John Hunter and Richard Shaw Abstract: With only a small exposure near the head of its eponymous dale, the Cressbrook Dale Lava is the least exposed of the major lava flows interbedded within the Carboniferous platform- carbonate succession of the Derbyshire Peak District. It underlies a large area of the limestone plateau between Longstone Edge and the Eyam and Hucklow edges. The recent closure of all of the quarries and underground mines in this area provided a stimulus to locate and compile the existing subsurface information relating to the lava-field and, supplemented by airborne geophysical survey results, to use these data to interpret the buried volcanic landscape. The same sub-surface data-set is used to interpret the spatial distribution of the overlying Litton Tuff. Within the regional north-south crustal extension that survey indicate that the outcrops of igneous rocks in affected central and northern Britain on the north side the White Peak are only part of a much larger volcanic of the Wales-Brabant High during the early part of the field, most of which is concealed at depth beneath Carboniferous, a province of subsiding platforms, tilt- Millstone Grit and Coal Measures farther east. Because blocks and half-grabens developed beneath a shallow no large volcano structures have been discovered so continental sea. Intra-plate magmatism accompanied far, geological literature describes the lavas in the the lithospheric thinning, with basic igneous rocks White Peak as probably originating from four separate erupting at different times from a number of small, local centres, each being active in a different area at different volcanic centres scattered across a region extending times (Smith et al., 2005). -

3 Avebury Info

AVEBURY HENGE & WEST KENNET AVENUE Information for teachers A henge is a circular area enclosed by a bank or ditch, Four or five thousand years ago there were as many as used for religious ceremonies in prehistoric times. 200-300 henges in use. They were mostly constructed Avebury is one of the largest henges in the British Isles. with a ditch inside a bank and some of them had stone Even today the bank of the henge is 5m above the or wooden structures inside them. Avebury has four modern ground level and it measures over one kilome- entrances, whereas most of the others have only one or tre all the way round. The stone circle inside the bank two. and ditch is the largest in Europe. How are the stones arranged? The outer circle of standing stones closely follows the circuit of the ditch. There were originally about 100 stones in this circle, of which 30 are still visible today. The positions of another 16 are marked with concrete pillars. Inside the northern and southern halves of the outer circle are two more stone circles, each about 100m in diameter. Only a small number of their original stones have survived. There were other stone settings inside these circles, including a three-sided group within the southern circle, known as ‘the Cove’. The largest stone that remains from this group weighs about 100 tonnes and is one of the largest megaliths in Britain. What is sarsen stone? Sarsen is a type of sandstone and is found all over the chalk downland of the Marlborough Downs. -

UNDER the EDGE INCORPORATING the PARISH MAGAZINE GREAT LONGSTONE, LITTLE LONGSTONE, ROWLAND, HASSOP, MONSAL HEAD, WARDLOW No

UNDER THE EDGE INCORPORATING THE PARISH MAGAZINE GREAT LONGSTONE, LITTLE LONGSTONE, ROWLAND, HASSOP, MONSAL HEAD, WARDLOW www.undertheedge.net No. 268 May 2021 ISSN 1466-8211 Stars in His Eyes The winner of the final category of the Virtual Photographic (IpheionCompetition uniflorum) (Full Bloom) with a third of all votes is ten year old Alfie Holdsworth Salter. His photo is of a Spring Starflower or Springstar , part of the onion and amyrillis family. The flowers are honey scented, which is no doubt what attracted the ant. Alfie is a keen photographer with his own Olympus DSLR camera, and this scene caught his eye under a large yew tree at the bottom of Church Lane. His creativity is not limited just to photography: Alfie loves cats and in Year 5 he and a friend made a comic called Cat Man! A total of 39 people took part in our photographic competition this year and we hope you had fun and found it an interesting challenge. We have all had to adapt our ways of doing things over the last year and transferring this competition to an online format, though different, has been a great success. Now that we are beginning to open up and get back to our normal lives, maybe this is the blueprint for the future of the competition? 39 people submitted a total of 124 photographs across the four categories, with nearly 100 taking part in voting for their favourite entry. Everyone who entered will be sent a feedback form: please fill it in withJane any Littlefieldsuggestions for the future. -

Brassington Conservation Area Appraisal

Brassington Conservation Area Appraisal January 2008 BRASSINGTON CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL page Summary 1 1. Brassington in Context 2 2 Origins & Development 3 • Topography & Geology • Historic Development 3. Archaeological Significance 13 4. Architectural and Historic Quality 15 • Key Buildings • Building Materials & Architectural Details 5. Setting of the Conservation Area 44 6. Landscape Appraisal 47 7. Analysis of Character 60 8. Negative Factors 71 9. Neutral Factors 75 10. Justification for Boundary 76 • Recommendations for Amendment 11. Conservation Policies & Legislation 78 • National Planning Guidance • Regional Planning Guidance • Local Planning Guidance Appendix 1 Statutory Designations (Listed Buildings) Sections 1-5 & 7-10 prepared by Mel Morris Conservation , Ipstones, Staffordshire ST10 2LY on behalf of Derbyshire Dales District Council All photographs within these sections have been taken by Mel Morris Conservation © September 2007 i BRASSINGTON CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL List of Figures Fig. 1 Aerial Photograph Fig. 2 Brassington in the Derbyshire Dales Fig. 3 Brassington Conservation Area Fig. 4 Brassington - Enclosure Map (inset of town plan) 1808 Fig. 5 First edition Ordnance Survey map of 1880 Fig. 6 Building Chronology Fig. 7 Historic Landscape Setting Fig. 8 Planning Designations: Trees & Woodlands Fig. 9 Landscape Appraisal Zones Fig. 10 Relationship of Structures & Spaces Fig. 11 Conservation Area Boundary - proposed areas for extension & exclusion Fig. 12 Conservation Area Boundary Approved January 2008 List of Historic Illustrations & Acknowledgements Pl. 1 Extract from aerial photograph (1974) showing lead mining landscape (© Derbyshire County Council 2006) Pl. 2 Late 19th century view of Well Street, Brassington (reproduced by kind permission of Tony Holmes) Pl. 3 Extract from Sanderson’s map of 20 Miles round Mansfield 1835 (by kind permission of Local Studies Library, Derbyshire County Council) Pl. -

Session 1 Time Travel in the Peak District from the Mesolithic to the Neolithic Aims of the Session Curriculum Links Resources

Stone Age to Iron Age KS2 Session 1 Time travel in the Peak District from the Mesolithic to the Neolithic Aims of the session The aim of this session is to explore the evidence of life in the local area from the Mesolithic to the Neolithic. Gather evidence in the gallery to create a video back at school about life in the Mesolithic times. Curriculum links This session will support pupils to develop a chronologically secure knowledge and understanding of British, local and world history, establishing clear narratives within and across the periods they study. They should note connections, contrasts and trends overtime and develop the appropriate use of historical terms. They should regularly address and sometimes devise historically valid questions about change, cause, similarity and difference, and significance. They should construct informed responses that involve thoughtful selection and organisation of relevant historical information. They should understand how our knowledge of the past is constructed from a range of sources. A visit to the Wonders of the Peak gallery will contribute to both an overview and a depth study to help pupils understand both the long arc of development and complexity of specific aspects of the content. Resources Handling collection, Stone Age Boy, DK Find out series, Stone Age Stone Age to Iron Age KS2 KS2 Session 1: 12,000 to 6,000 years ago The aim of this session is to explore the evidence of life in the local area from the Mesolithic to the Neolithic. Gather evidence in the gallery to create a video back at school about life in the Mesolithic times. -

Green Lanes Annual Report 2020

[Type text] OpenGreen Access Lanes Annual Newsletter Report 2019/20 May 2020 Green lanes are tracks across the National Park used by walkers, cyclists, horse riders and motor vehicles. This is our third annual report. It reports on the work we have done in partnership with others over this last year. 1) Involvement Peak District Local Access Forum Our Local Access Forum (LAF), the first to be established in this country, celebrates its 20th anniversary this year. For the last 10 years it has had a sub-group looking at the issues of recreational motorised vehicles and green lanes. LAF members come from a wide range of backgrounds and interests. We are grateful for their expertise, advice and guidance provided and their collaborative consensus-based approach. In June 2019, LAF members met officers from Sheffield City Council, Eastern Moors Partnership and Derbyshire Police on the Houndkirk Road to consider how to encourage vehicle users to Stay on Track. Damage to the track verges was looked at and it was clear that we had to change the way of thinking to value the surroundings more than the ability to drive anywhere at will. Options for signage, barriers, reinstatement and enforcement were also considered. www.peakdistrict.gov.uk/vehicles 1 [Type text] OpenGreen Access Lanes Annual Newsletter Report 2019/20 Two Forums The first joint Forum meeting between Peak District Local Access Forum and the Stanage Forum was held in March 2020 on Long Causeway at Stanage. Members discussed enhancing accessibility and considered the potential for a Miles without Stiles route. We also looked at opportunities that the route provides for people to explore the moorland habitat.