Languages of the World--Indo-European

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impact of Hittite and Tocharian: Rethinking Indo-European in the 20Th Century and Beyond

The Impact of Hittite and Tocharian: Rethinking Indo-European in the 20th Century and Beyond The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Jasanoff, Jay. 2017. The Impact of Hittite and Tocharian: Rethinking Indo-European in the 20th Century and Beyond. In Handbook of Comparative and Historical Indo-European Linguistics, edited by Jared Klein, Brian Joseph, and Matthias Fritz, 31-53. Munich: Walter de Gruyter. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:41291502 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA 18. The Impact of Hittite and Tocharian ■■■ 35 18. The Impact of Hittite and Tocharian: Rethinking Indo-European in the Twentieth Century and Beyond 1. Two epoch-making discoveries 4. Syntactic impact 2. Phonological impact 5. Implications for subgrouping 3. Morphological impact 6. References 1. Two epoch-making discoveries The ink was scarcely dry on the last volume of Brugmann’s Grundriß (1916, 2nd ed., Vol. 2, pt. 3), so to speak, when an unexpected discovery in a peripheral area of Assyriol- ogy portended the end of the scholarly consensus that Brugmann had done so much to create. Hrozný, whose Sprache der Hethiter appeared in 1917, was not primarily an Indo-Europeanist, but, like any trained philologist of the time, he could see that the cuneiform language he had deciphered, with such features as an animate nom. -

Variationist Linguistics Meets CONTACT Linguistics

Published in: Lenz, Alexandra N./Maselko, Mateusz (Eds.): VARIATIONist Linguistics meets CONTACT Linguistics. - Göttingen: V&R unipress, 2020. Pp. 25-49. (Wiener Arbeiten zur Linguistik 6) DOI: https://doi.org/10.14220/9783737011440.25 Katharina Dück Language Contact and Language Attitudes of Caucasian Germans in Today’sCaucasus and Germany Abstract: This article examines the language contact situation as well as the language attitudes of the Caucasian Germans, descendants of German-born inhabitants of the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union who emigrated in 1816/ 17 to areas of Transcaucasia. After deportationsand migrations, the group of Caucasian Germans now consists of those who havesince emigrated to Germany and those who still liveinthe South Caucasus. It’sthe first time that socio- linguistic methodshavebeen used to record data from the generationwho ex- perienced living in the South Caucasusand in Germanyaswell as from two succeeding generations. Initial results will be presented below with afocus on the language contact constellations of German varieties as well as on consequences of language contact and language repression, which both affect language attitudes. Keywords: language contact, migration, variation, language attitudes, identity Abstract: Im Zentrum der nachstehendenBetrachtungen stehen die Sprachkon- taktsituation sowie die Spracheinstellungen der Kaukasiendeutschen, Nachfah- ren deutschstämmiger Einwohner des Russischen Reichs und der Sowjetunion, die 1816/17inGebiete Transkaukasiensausgewandert sind. Nach Deportationen -

Year 18 September 1964 Maladies Quarantenaires

Relevé épidém. hebd. ) 1964, 39, 453-464 N** 38 Wkly Epidem. Ree. | ORGANISATION MONDIALE DE LA SANTÉ WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION GENÈVE GENEVA RELEVÉ ÉPIDÉMIOLOGIQUE HEBDOMADAIRE WEEKLY EPIDEMIOLOGICAL RECORD Notifications et infoimations se rapportant à l’application Notifications under and information on the application of the du Règlement sanitaire international et notes relatives à la International Sanitary Regulations and notes on current incidence fréquence de certaines maladies of certain diseases Service de la Quarantaine internationale Internationai Quarantine Service Adresse télégraphique; EPDDNATIONS, GENÈVE Telegraphic address: EPIDNATIONS, GENÈVE 18 SEPTEMBRE 1964 39® ANNÉE — 39«* YEAR 18 SEPTEMBER 1964 MALADIES QUARANTENAIRES ■ QUARANIÎNABLE DISEASES Territoires infectés an 17 septembre 1964 ■ infected areas as on 17 September 1964 Notifications reçues aux termes du Règlement sanitaire international Notifications received under the International Sanitary Regulations relating concernant les circonscriptions infectées ou les territoires où la présence to infected local areas and to areas in which the presence of quarantinable de maladies qiuirantcnaires a été signalée (voir page 414). diseases was reported (see page 414). ■ « Circonscriptions ou territoires notifiés aux termes de Tarticle 3 à la ■ = Areas notified under Article 3 on the date indicated. date donnée. Autres territoires où la présence de maladies quarantenaires a été notifiée Other areas in which the presence of quarantinable diseases was notified aux termes des articles 4, 5 et 9 a): under Articles 4, 5 and 9 (a): A = pendant la période indiquée sous le nom de chaque maladie; A =: during the period indicated under the heading of each disease; B — antérieurement à la période indiquée sous le nom de chaque maladie; B = prior to the period indicated under the heading of each disease; • = territoires nouvellement infectés. -

Dynamics of Religious Ritual: Migration and Adaptation in Early Medieval Britain

Dynamics of Religious Ritual: Migration and Adaptation in Early Medieval Britain A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Brooke Elizabeth Creager IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Peter S. Wells August 2019 Brooke Elizabeth Creager 2019 © For my Mom, I could never have done this without you. And for my Grandfather, thank you for showing me the world and never letting me doubt I can do anything. Thank you. i Abstract: How do migrations impact religious practice? In early Anglo-Saxon England, the practice of post-Roman Christianity adapted after the Anglo-Saxon migration. The contemporary texts all agree that Christianity continued to be practiced into the fifth and sixth centuries but the archaeological record reflects a predominantly Anglo-Saxon culture. My research compiles the evidence for post-Roman Christian practice on the east coast of England from cemeteries and Roman churches to determine the extent of religious change after the migration. Using the case study of post-Roman religion, the themes religion, migration, and the role of the individual are used to determine how a minority religion is practiced during periods of change within a new culturally dominant society. ii Table of Contents Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………...ii List of Figures ……………………………………………………………………………iv Preface …………………………………………………………………………………….1 I. Religion 1. Archaeological Theory of Religion ...………………………………………………...3 II. Migration 2. Migration Theory and the Anglo-Saxon Migration ...……………………………….42 3. Continental Ritual Practice before the Migration, 100 BC – AD 400 ………………91 III. Southeastern England, before, during and after the Migration 4. Contemporary Accounts of Religion in the Fifth and Sixth Centuries……………..116 5. -

Greek-Anatolian Language Contact and the Settlement of Pamphylia

CHRISTINA SKELTON Greek-Anatolian Language Contact and the Settlement of Pamphylia The Ancient Greek dialect of Pamphylia shows extensive influence from the nearby Anatolian languages. Evidence from the linguistics of Greek and Anatolian, sociolinguistics, and the histor- ical and archaeological record suggest that this influence is due to Anatolian speakers learning Greek as a second language as adults in such large numbers that aspects of their L2 Greek became fixed as a part of the main Pamphylian dialect. For this linguistic development to occur and persist, Pamphylia must initially have been settled by a small number of Greeks, and remained isolated from the broader Greek-speaking community while prevailing cultural atti- tudes favored a combined Greek-Anatolian culture. 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 BACKGROUND The Greek-speaking world of the Archaic and Classical periods (ca. ninth through third centuries BC) was covered by a patchwork of different dialects of Ancient Greek, some of them quite different from the Attic and Ionic familiar to Classicists. Even among these varied dialects, the dialect of Pamphylia, located on the southern coast of Asia Minor, stands out as something unusual. For example, consider the following section from the famous Pamphylian inscription from Sillyon: συ Διϝι̣ α̣ ̣ και hιιαροισι Μανεˉ[ς .]υαν̣ hελε ΣελυW[ι]ιυ̣ ς̣ ̣ [..? hι†ια[ρ]α ϝιλ̣ σιι̣ ọς ̣ υπαρ και ανιιας̣ οσα περ(̣ ι)ι[στα]τυ ̣ Wοικ[. .] The author would like to thank Sally Thomason, Craig Melchert, Leonard Neidorf and the anonymous reviewer for their valuable input, as well as Greg Nagy and everyone at the Center for Hellenic Studies for allowing me to use their library and for their wonderful hospitality during the early stages of pre- paring this manuscript. -

Introduction Ti Alkire and Carol Rosen Excerpt More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-71784-7 - Romance Languages: A Historical Introduction Ti Alkire and Carol Rosen Excerpt More information Introduction Latin and the Romance languages occupy a vast space along at least three dimensions: geographical, temporal, and social. Once the language of a small town on the Tiber River in Latium, Latin was carried far afield with the expan- sion of Roman power. The Empire reached its greatest extent under the reign of the emperor Trajan (98–117 CE), at which point it included modern-day Britain, Portugal, Spain, France, Italy, Switzerland, Austria, and the Balkan peninsula, as well as immense territories in the Eastern Mediterranean and beyond, mak- ing it by far the largest single state the Western world had ever known. Even those distances are dwarfed by the extent of Western European colonial expan- sion in the 1500s and 1600s, which brought Spanish to most of Latin America and the Caribbean, Portuguese to Brazil, French to Canada, and all three to their many outposts around the world, where they engendered some robust cre- oles. On the time dimension, the colloquial speech that underlies the Romance languages was already a constant presence during the seven centuries that saw Rome grow from village to empire – and then their history still has twenty cen- turies to go. Their uses in society extend to every level and facet of activity from treasured world literature to instant messaging. A truly panoramic account of Romance linguistic history would find few readers and probably no writers. The scope has to be limited somehow. -

Copyright by Cécile Hélène Christiane Rey 2010

Copyright by Cécile Hélène Christiane Rey 2010 The Dissertation Committee for Cécile Hélène Christiane Rey certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Planning language practices and representations of identity within the Gallo community in Brittany: A case of language maintenance Committee: _________________________________ Jean-Pierre Montreuil, Supervisor _________________________________ Cinzia Russi _________________________________ Carl Blyth _________________________________ Hans Boas _________________________________ Anthony Woodbury Planning language practices and representations of identity within the Gallo community in Brittany: A case of language maintenance by Cécile Hélène Christiane Rey, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December, 2010 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my parents and my family for their patience and support, their belief in me, and their love. I would like to thank my supervisor Jean-Pierre Montreuil for his advice, his inspiration, and constant support. Thank you to my committee members Cinzia Russi, Carl Blyth, Hans Boas and Anthony Woodbury for their guidance in this project and their understanding. Special thanks to Christian Lefeuvre who let me stay with him during the summer 2009 in Langan and helped me realize this project. For their help and support, I would like to thank Rosalie Grot, Pierre Gardan, Christine Trochu, Shaun Nolan, Bruno Chemin, Chantal Hermann, the associations Bertaèyn Galeizz, Chubri, l’Association des Enseignants de Gallo, A-Demórr, and Gallo Tonic Liffré. For financial support, I would like to thank the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin for the David Bruton, Jr. -

“Being Neutral Is Our Biggest Crime”

India “Being Neutral HUMAN RIGHTS is Our Biggest Crime” WATCH Government, Vigilante, and Naxalite Abuses in India’s Chhattisgarh State “Being Neutral is Our Biggest Crime” Government, Vigilante, and Naxalite Abuses in India’s Chhattisgarh State Copyright © 2008 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-356-0 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org July 2008 1-56432-356-0 “Being Neutral is Our Biggest Crime” Government, Vigilante, and Naxalite Abuses in India’s Chhattisgarh State Maps........................................................................................................................ 1 Glossary/ Abbreviations ..........................................................................................3 I. Summary.............................................................................................................5 Government and Salwa Judum abuses ................................................................7 Abuses by Naxalites..........................................................................................10 Key Recommendations: The need for protection and accountability.................. -

Ldc Final Merit

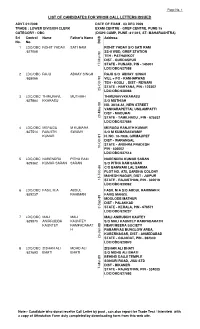

Page No. 1 LIST OF CANDIDATES FOR WHOM CALL LETTERS ISSUED ADVT-01/2009 DATE OF EXAM - 03 DEC 2009 TRADE : LOWER DIVISION CLERK EXAM CENTRE - GREF CENTRE, PUNE-15 CATEGORY - OBC (DIGHI CAMP, PUNE -411015, ST- MAHARASHTRA) Srl Control Name Father's Name Address No. No. DOB 1 LDC/OBC ROHIT YADAV SATI RAM ROHIT YADAV S/O SATI RAM /627088 SS-II WSD, GREF STATION TEH - PATHANKOT DIST - GURDASPUR STATE - PUNJAB, PIN - 145001 17-Mar-90 LDC/OBC/627088 2 LDC/OBC RAJU ABHAY SINGH RAJU S/O ABHAY SINGH /628066 VILL + PO - KANHARWAS TEH - KOSLI , DIST - REWARI STATE - HARYANA, PIN - 123302 25-Oct-90 LDC/OBC/628066 3 LDC/OBC THIRUNAVL MUTHIAH THIRUNAVVKKARASU /627884 KKARASU S/O MUTHIAH NO. 38/34 A1, NEW STREET VANNARAPETTAI, USILAMPATTI DIST - MADURAI 20-May-88 STATE - TAMILNADU , PIN - 625532 LDC/OBC/627884 4 LDC/OBC MERUGU M KUMARA MERUGU RANJITH KUMAR /627514 RANJITH SWAMY S/O M KUMARASWAMY KUMAR H. NO. 10-7936, GIRMAJIPET DIST - WARANGAL STATE - ANDHRA PRADESH 10-Oct-81 PIN - 506002 LDC/OBC/627514 5 LDC/OBC NARENDRA PITHA RAM NARENDRA KUMAR SARAN /629362 KUMAR SARAN SARAN S/O PITHA RAM SARAN C/O BANWARI LAL SARMA PLOT NO. A75, SARDHA COLONY MAHESH NAGAR, DIST - JAIPUR 15-Feb-86 STATE - RAJASTHAN, PIN - 302019 LDC/OBC/629362 6 LDC/OBC FASIL M.A ABDUL FASIL M A S/O ABDUL RAHIMAN K /629237 RAHIMAN FARIS MANZIL MOOLODE MATHUR DIST - PALAKKAD 2-Sep-89 STATE - KERALA, PIN - 678571 LDC/OBC/629237 7 LDC/OBC MALI MALI MALI ANIRUDDH KAUTEY /629870 ANIRRUDDH KAUNTEY S/O MALI KAUNTEY RAMPADARATH KAUNTEY RAMPADARAT NEAR MEERA SOCIETY H RABARIVAS BUNGLOW AREA, KUBERNAGAR, DIST - AHMEDABAD 23-Jan-88 STATE - GUJARAT, PIN - 382340 LDC/OBC/629870 8 LDC/OBC ZISHAN ALI MOHD ALI ZISHAN ALI BHATI /627693 BHATI BHATI S/O MOHD ALI BHATI BEHIND DAUJI TEMPLE SONGRI ROAD, JISU STD DIST - BIKANER 7-Mar-89 STATE - RAJASTHAN, PIN - 334005 LDC/OBC/627693 Note:- Candidate who donot receive Call Letter by post , can also report for Trade Test / Interview with a copy of Attestation Form duly completed by downloading form from this web site. -

Prioritizing African Languages: Challenges to Macro-Level Planning for Resourcing and Capacity Building

Prioritizing African Languages: Challenges to macro-level planning for resourcing and capacity building Tristan M. Purvis Christopher R. Green Gregory K. Iverson University of Maryland Center for Advanced Study of Language Abstract This paper addresses key considerations and challenges involved in the process of prioritizing languages in an area of high linguistic di- versity like Africa alongside other world regions. The paper identifies general considerations that must be taken into account in this process and reviews the placement of African languages on priority lists over the years and across different agencies and organizations. An outline of factors is presented that is used when organizing resources and planning research on African languages that categorizes major or crit- ical languages within a framework that allows for broad coverage of the full linguistic diversity of the continent. Keywords: language prioritization, African languages, capacity building, language diversity, language documentation When building language capacity on an individual or localized level, the question of which languages matter most is relatively less complicated than it is for those planning and providing for language capabilities at the macro level. An American anthropology student working with Sierra Leonean refugees in Forecariah, Guinea, for ex- ample, will likely know how to address and balance needs for lan- guage skills in French, Susu, Krio, and a set of other languages such as Temne and Mandinka. An education official or activist in Mwanza, Tanzania, will be concerned primarily with English, Swahili, and Su- kuma. An administrator of a grant program for Less Commonly Taught Languages, or LCTLs, or a newly appointed language authori- ty for the United States Department of Education, Department of Commerce, or U.S. -

The Shared Lexicon of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic

THE SHARED LEXICON OF BALTIC, SLAVIC AND GERMANIC VINCENT F. VAN DER HEIJDEN ******** Thesis for the Master Comparative Indo-European Linguistics under supervision of prof.dr. A.M. Lubotsky Universiteit Leiden, 2018 Table of contents 1. Introduction 2 2. Background topics 3 2.1. Non-lexical similarities between Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 3 2.2. The Prehistory of Balto-Slavic and Germanic 3 2.2.1. Northwestern Indo-European 3 2.2.2. The Origins of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 4 2.3. Possible substrates in Balto-Slavic and Germanic 6 2.3.1. Hunter-gatherer languages 6 2.3.2. Neolithic languages 7 2.3.3. The Corded Ware culture 7 2.3.4. Temematic 7 2.3.5. Uralic 9 2.4. Recapitulation 9 3. The shared lexicon of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 11 3.1. Forms that belong to the shared lexicon 11 3.1.1. Baltic-Slavic-Germanic forms 11 3.1.2. Baltic-Germanic forms 19 3.1.3. Slavic-Germanic forms 24 3.2. Forms that do not belong to the shared lexicon 27 3.2.1. Indo-European forms 27 3.2.2. Forms restricted to Europe 32 3.2.3. Possible Germanic borrowings into Baltic and Slavic 40 3.2.4. Uncertain forms and invalid comparisons 42 4. Analysis 48 4.1. Morphology of the forms 49 4.2. Semantics of the forms 49 4.2.1. Natural terms 49 4.2.2. Cultural terms 50 4.3. Origin of the forms 52 5. Conclusion 54 Abbreviations 56 Bibliography 57 1 1. -

Internal Classification of Indo-European Languages: Survey

Václav Blažek (Masaryk University of Brno, Czech Republic) On the internal classification of Indo-European languages: Survey The purpose of the present study is to confront most representative models of the internal classification of Indo-European languages and their daughter branches. 0. Indo-European 0.1. In the 19th century the tree-diagram of A. Schleicher (1860) was very popular: Germanic Lithuanian Slavo-Lithuaian Slavic Celtic Indo-European Italo-Celtic Italic Graeco-Italo- -Celtic Albanian Aryo-Graeco- Greek Italo-Celtic Iranian Aryan Indo-Aryan After the discovery of the Indo-European affiliation of the Tocharian A & B languages and the languages of ancient Asia Minor, it is necessary to take them in account. The models of the recent time accept the Anatolian vs. non-Anatolian (‘Indo-European’ in the narrower sense) dichotomy, which was first formulated by E. Sturtevant (1942). Naturally, it is difficult to include the relic languages into the model of any classification, if they are known only from several inscriptions, glosses or even only from proper names. That is why there are so big differences in classification between these scantily recorded languages. For this reason some scholars omit them at all. 0.2. Gamkrelidze & Ivanov (1984, 415) developed the traditional ideas: Greek Armenian Indo- Iranian Balto- -Slavic Germanic Italic Celtic Tocharian Anatolian 0.3. Vladimir Georgiev (1981, 363) included in his Indo-European classification some of the relic languages, plus the languages with a doubtful IE affiliation at all: Tocharian Northern Balto-Slavic Germanic Celtic Ligurian Italic & Venetic Western Illyrian Messapic Siculian Greek & Macedonian Indo-European Central Phrygian Armenian Daco-Mysian & Albanian Eastern Indo-Iranian Thracian Southern = Aegean Pelasgian Palaic Southeast = Hittite; Lydian; Etruscan-Rhaetic; Elymian = Anatolian Luwian; Lycian; Carian; Eteocretan 0.4.