“Go West” in Cochinchina. Chinese and Vietnamese Illicit Activities in the Transbassac (C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Morphology of Water-Based Housing in Mekong Delta, Vietnam

MATEC Web of Conferences 193, 04005 (2018) https://doi.org/10.1051/matecconf/201819304005 ESCI 2018 Morphology of water-based housing in Mekong delta, Vietnam Thi Hong Hanh Vu1,* and Viet Duong1 1University of Architecture Ho Chi Minh City, 196 Pasteur, District 1, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam Abstract. A long time ago, houses along and on the water have been distinctive elements of the water-based Mekong Delta. Over a long history of development, these morphological settlements have been deteriorated due to environmental, economic, and cultural changes from water to mainland, resulted in the reductions of water-based communities and architectural deterioration. This research is aimed to analyze the distinguishing values of those housing types/communities in 5 chosen popular water-based settlements in Mekong Delta region to give positive recommendations for further changes. 1 Introduction Mekong Delta is located in the South of Vietnam, downstream of the Mekong River. This is a nutrious plain with dense water channels. People here have chosen their settlements to be near, in order of priority: markets – rivers – friends –roads/streets/routes - and farmlands (Nhất cận thị, nhị cận giang, tam cận lân, tứ cận lộ, ngũ cận điền). When the population increased, they started to move inward the land; as a result, their living culture have gradually changed, so have their houses [1-3]. Over long history of exploitation, the local inhabitants and migrants from other parts of Vietnam and nearby countries have turned this Mekong delta to a rich and distinctive society with diverse ethnic communities, cultures and beliefs, living harmoniously together. -

Vietnam Maximizing Finance for Development in the Energy Sector

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized VIETNAM MAXIMIZING FINANCE FOR DEVELOPMENT IN THE ENERGY SECTOR DECEMBER 2018 Public Disclosure Authorized ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report was prepared by a core team led by Franz Gerner (Lead Energy Specialist, Task Team Leader) and Mark Giblett (Senior Infrastructure Finance Specialist, Co-Task Team Leader). The team included Alwaleed Alatabani (Lead Financial Sector Specialist), Oliver Behrend (Principal Investment Officer, IFC), Sebastian Eckardt (Lead Country Economist), Vivien Foster (Lead Economist), and David Santley (Senior Petroleum Specialist). Valuable inputs were provided by Pedro Antmann (Lead Energy Specialist), Ludovic Delplanque (Program Officer), Nathan Engle (Senior Climate Change Specialist), Hang Thi Thu Tran (Investment Officer, IFC), Tim Histed (Senior Business Development Officer, MIGA), Hoa Nguyen Thi Quynh (Financial Management Consultant), Towfiqua Hoque (Senior Infrastructure Finance Specialist), Hung Tan Tran (Senior Energy Specialist), Hung Tien Van (Senior Energy Specialist), Kai Kaiser (Senior Economist), Ketut Kusuma (Senior Financial Sector Specialist, IFC), Ky Hong Tran (Senior Energy Specialist), Alice Laidlaw (Principal Investment Officer, IFC), Mai Thi Phuong Tran (Senior Financial Management Specialist), Peter Meier (Energy Economist, Consultant), Aris Panou (Counsel), Alejandro Perez (Senior Investment Officer, IFC), Razvan Purcaru (Senior Infrastructure Finance Specialist), Madhu Raghunath (Program Leader), Thi Ba -

Vietnam) to Attract Overseas Chinese (From 1600 to 1777

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 24, Issue 3, Ser. 1 (March. 2019) 74-77 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org The Policy of the Cochinchina Government (Vietnam) to Attract Overseas Chinese (from 1600 to 1777) Huynh Ngoc Dang1, Cao Dai Tri2 2Doctor of history 1Institute of Cultural History - Hunan Normal University (China) Abstract: Aiming at building a powerful administration to survive and secede, Nguyen clan in Cochinchina was smart and skillful in implementing policies to attract significant resources to serve the reclamation in southern Vietnam, build a prosperous kingdom of Cochinchina and even go further: to create a position to counterbalance and balance the political-military power with Siam (Thailand) in the Indochina Peninsula. One of the critical resources that the feudal government in Cochinchina smartly enlisted and attracted is the Chinese immigrant groups living in Vietnam. Keywords: Cochinchina government, Nguyen clan, Chinese, Policy, Vietnam. I. Overview of the Migration of Chinese to Cochinchina. It is possible to generalize the process of Chinese migration toward Cochinchina into three following stages: Phase 1: From the end of the 16th century to the year 1645. This period has two main events affecting the migration of Chinese to Cochinchina, namely: In 1567, Longqing Emperor (China) issued an ordinance allowing his civilians to go abroad for trading after almost 200 years of maintaining maritime order banning (Vietnamese: Thốn bản bất hạ hải) - do not give permission for an inch of wood to overseas. The second event was Nguyen Hoang’s returning to Thuan - Quang in 1600, began to implement the idea of secession. -

Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Dengue Epidemics, Southern Vietnam Hoang Quoc Cuong, Nguyen Thanh Vu, Bernard Cazelles, Maciej F

Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Dengue Epidemics, Southern Vietnam Hoang Quoc Cuong, Nguyen Thanh Vu, Bernard Cazelles, Maciej F. Boni, Khoa T.D. Thai, Maia A. Rabaa, Luong Chan Quang, Cameron P. Simmons, Tran Ngoc Huu, and Katherine L. Anders An improved understanding of heterogeneities in den- drive annual seasonality; intrinsic factors associated with gue virus transmission might provide insights into biological human host demographics, population immunity, and the and ecologic drivers and facilitate predictions of the mag- virus, drive the multiannual dynamics (5–7). Analyses from nitude, timing, and location of future dengue epidemics. To Southeast Asia have demonstrated multiannual oscillations investigate dengue dynamics in urban Ho Chi Minh City and in dengue incidence (8–10), which have been variably as- neighboring rural provinces in Vietnam, we analyzed a 10- sociated with macroclimatic weather cycles (exemplified year monthly time series of dengue surveillance data from southern Vietnam. The per capita incidence of dengue was by the El Niño Southern Oscillation) in different settings lower in Ho Chi Minh City than in most rural provinces; an- and with changes in population demographics in Thailand nual epidemics occurred 1–3 months later in Ho Chi Minh (11). In Thailand, a spatiotemporal analysis showed that the City than elsewhere. The timing and the magnitude of an- multiannual cycle emanated from Bangkok out to more dis- nual epidemics were significantly more correlated in nearby tant provinces (9). districts than in remote districts, suggesting that local bio- Knowledge of spatial and temporal patterns in dengue logical and ecologic drivers operate at a scale of 50–100 incidence at a subnational level is relevant for 2 main rea- km. -

China Versus Vietnam: an Analysis of the Competing Claims in the South China Sea Raul (Pete) Pedrozo

A CNA Occasional Paper China versus Vietnam: An Analysis of the Competing Claims in the South China Sea Raul (Pete) Pedrozo With a Foreword by CNA Senior Fellow Michael McDevitt August 2014 Unlimited distribution Distribution unlimited. for public release This document contains the best opinion of the authors at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the sponsor. Cover Photo: South China Sea Claims and Agreements. Source: U.S. Department of Defense’s Annual Report on China to Congress, 2012. Distribution Distribution unlimited. Specific authority contracting number: E13PC00009. Copyright © 2014 CNA This work was created in the performance of Contract Number 2013-9114. Any copyright in this work is subject to the Government's Unlimited Rights license as defined in FAR 52-227.14. The reproduction of this work for commercial purposes is strictly prohibited. Nongovernmental users may copy and distribute this document in any medium, either commercially or noncommercially, provided that this copyright notice is reproduced in all copies. Nongovernmental users may not use technical measures to obstruct or control the reading or further copying of the copies they make or distribute. Nongovernmental users may not accept compensation of any manner in exchange for copies. All other rights reserved. This project was made possible by a generous grant from the Smith Richardson Foundation Approved by: August 2014 Ken E. Gause, Director International Affairs Group Center for Strategic Studies Copyright © 2014 CNA FOREWORD This legal analysis was commissioned as part of a project entitled, “U.S. policy options in the South China Sea.” The objective in asking experienced U.S international lawyers, such as Captain Raul “Pete” Pedrozo, USN, Judge Advocate Corps (ret.),1 the author of this analysis, is to provide U.S. -

1. Oil and Gas Exploration & Production

1. Oil and gas exploration & production This is the core business of PVN, the current metres per year. By 2012, we are planning to achieve reserves are approximated of 1.4 billion cubic metres 20 million tons of oil and 15 billion cubic metres of of oil equivalent. In which, oil reserve is about 700 gas annually. million cubic metres and gas reserve is about 700 In this area, we are calling for foreign investment in million cubic metres of oil equivalent. PVN has both of our domestic blocks as well as oversea explored more than 300 million cubic metres of oil projects including: Blocks in Song Hong Basin, Phu and about 94 billion cubic metres of gas. Khanh Basin, Nam Con Son Basin, Malay Tho Chu, Until 2020, we are planning to increase oil and gas Phu Quoc Basin, Mekong Delta and overseas blocks reserves to 40-50 million cubic metres of oil in Malaysia, Uzbekistan, Laos, and Cambodia. equivalent per year; in which the domestic reserves The opportunities are described in detail on the increase to 30-35 million cubic metres per year and following pages. oversea reserves increase to 10-15 million cubic Overseas Oil and Gas Exploration and Production Projects RUSSIAN FEDERATION Rusvietpetro: A Joint Venture with Zarubezhneft Gazpromviet: A Joint Venture with Gazprom UZBEKISTAN ALGERIA Petroleum Contracts, Blocks Kossor, Molabaur Petroleum Contract, Study Agreement in Bukharakhiva Block 433a & 416b MONGOLIA Petroleum Contract, Block Tamtsaq CUBA Petroleum Contract, Blocks 31, 32, 42, 43 1. Oil and gas exploration & production e) LAO PDR Petroleum Contract, Block Champasak CAMBODIA 2. -

Indians As French Citizens in Colonial Indochina, 1858-1940 Natasha Pairaudeau

Indians as French Citizens in Colonial Indochina, 1858-1940 by Natasha Pairaudeau A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of London School of Oriental and African Studies Department of History June 2009 ProQuest Number: 10672932 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672932 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract This study demonstrates how Indians with French citizenship were able through their stay in Indochina to have some say in shaping their position within the French colonial empire, and how in turn they made then' mark on Indochina itself. Known as ‘renouncers’, they gained their citizenship by renoimcing their personal laws in order to to be judged by the French civil code. Mainly residing in Cochinchina, they served primarily as functionaries in the French colonial administration, and spent the early decades of their stay battling to secure recognition of their electoral and civil rights in the colony. Their presence in Indochina in turn had an important influence on the ways in which the peoples of Indochina experienced and assessed French colonialism. -

Indigenous Cultures of Southeast Asia: Language, Religion & Sociopolitical Issues

Indigenous Cultures of Southeast Asia: Language, Religion & Sociopolitical Issues Eric Kendrick Georgia Perimeter College Indigenous vs. Minorities • Indigenous groups are minorities • Not all minorities are indigenous . e.g. Chinese in SE Asia Hmong, Hà Giang Province, Northeast Vietnam No Definitive Definition Exists • Historical ties to a particular territory • Cultural distinctiveness from other groups • Vulnerable to exploitation and marginalization by colonizers or dominant ethnic groups • The right to self-Identification Scope • 70+ countries • 300 - 350 million (6%) • 4,000 – 5,000 distinct peoples • Few dozen to several hundred thousand Some significantly exposed to colonizing or expansionary activities Others comparatively isolated from external or modern influence Post-Colonial Developments • Modern society has encroached on territory, diminishing languages & cultures • Many have become assimilated or urbanized Categories • Pastoralists – Herd animals for food, clothing, shelter, trade – Nomadic or Semi-nomadic – Common in Africa • Hunter-Gatherers – Game, fish, birds, insects, fruits – Medicine, stimulants, poison – Common in Amazon • Farmers – Small scale, nothing left for trade – Supplemented with hunting, fishing, gathering – Highlands of South America Commonly-known Examples • Native Americans (Canada – First Nations people) • Inuit (Eskimos) • Native Hawaiians • Maori (New Zealand) • Aborigines (Australia) Indigenous Peoples Southeast Asia Mainland SE Asia (Indochina) • Vietnam – 53 / 10 M (14%) • Cambodia – 24 / 197,000 -

Phan Bội Châu and the Imagining of Modern Vietnam by Matthew a Berry a Dissertation Submitted in Partia

Confucian Terrorism: Phan Bội Châu and the Imagining of Modern Vietnam By Matthew A Berry A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Wen-hsin Yeh, Chair Professor Peter Zinoman Professor Emeritus Lowell Dittmer Fall 2019 Abstract Confucian Terrorism: Phan Bội Châu and the Imagining of Modern Vietnam by Matthew A Berry Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Wen-hsin Yeh, Chair This study considers the life and writings of Phan Bội Châu (1867-1940), a prominent Vietnamese revolutionary and nationalist. Most research on Phan Bội Châu is over forty years old and is contaminated by historiographical prejudices of the Vietnam War period. I seek to re- engage Phan Bội Châu’s writings, activities, and connections by closely analyzing and comparing his texts, using statistical and geographical systems techniques (GIS), and reconsidering previous juridical and historiographical judgments. My dissertation explores nationalism, modernity, comparative religion, literature, history, and law through the life and work of a single individual. The theoretical scope of this dissertation is intentionally broad for two reasons. First, to improve upon work already done on Phan Bội Châu it is necessary to draw on a wider array of resources and insights. Second, I hope to challenge Vietnam’s status as a historiographical peculiarity by rendering Phan Bội Châu’s case comparable with other regional and global examples. The dissertation contains five chapters. The first is a critical analysis of Democratic Republic of Vietnam and Western research on Phan Bội Châu. -

Exonyms of Vietnam's Vinh Bac Bo (Gulf of Tonkin)

Exonyms of Vietnam's Vinh Bac Bo (Gulf of Tonkin) POKOLY Béla* The presentation is exploring the various exonyms of this south-east Asian gulf, including some historical allonyms. Tonkin is the traditional historical name in most foreign languages for the northern part of Vietnam. Both the local Vietnamese and Chinese names for the feature mean in essence the same thing: “north bay”, even though it lies at the southern part of China. This commonly used meaning also helps co-operation and understanding in a region that saw so much suffering in the 20th century. The Gulf of Tonkin as is known in the English language, is a north-western portion of the South China Sea with an approximate area of 126,000 square kilometres. Its extent is larger than the Gulfs of Bothnia and Finland combined, it is a much more open sea area, with Vietnam (763 km) and China (695 km) sharing its coastlines. Bordered by the northern part of Vietnam, China's southern coast of Guangxi Autonomous Region, Leizhou Peninsula and Hainan Island, it is outside the disputed maritime area further out in the South China Sea. The local names for the feature are Vinh Bac Bo in Vietnamese and 北部湾 (Pinyin Beibu Wan) in Chinese. (Fig.1) The toponym gained worldwide attention in 1964 when the controversial Gulf of Tonkin Incident marked the starting point of the escalation of the Vietnam War. The paper does not wish to deal with this event, but tries to present some aspects of the exonyms and local names of this marine feature over time. -

Crossing Cultural, National, and Racial Boundaries: Portraits of Diplomats and the Pre-Colonial French-Cochinchinese Exchange, 1787-1863

CROSSING CULTURAL, NATIONAL, AND RACIAL BOUNDARIES: PORTRAITS OF DIPLOMATS AND THE PRE-COLONIAL FRENCH-COCHINCHINESE EXCHANGE, 1787-1863 Ashley Bruckbauer A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Art. Chapel Hill 2013 Approved by: Mary D. Sheriff Lyneise Williams Wei-Cheng Lin © 2013 Ashley Bruckbauer ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT ASHLEY BRUCKBAUER: Crossing Cultural, National, and Racial Boundaries: Portraits of Diplomats and the pre-colonial French-Cochinchinese Exchange, 1787-1863 (Under the direction of Dr. Mary D. Sheriff) In this thesis, I examine portraits of diplomatic figures produced between two official embassies from Cochinchina to France in 1787 and 1863 that marked a pre- colonial period of increasing contact and exchange between the two Kingdoms. I demonstrate these portraits’ departure from earlier works of diplomatic portraiture and French depictions of foreigners through a close visual analysis of their presentation of the sitters. The images foreground the French and Cochinchinese diplomats crossing cultural boundaries of costume and customs, national boundaries of loyalty, and racial boundaries of blood. By depicting these individuals as mixed or hybrid, I argue that the works both negotiated and complicated eighteenth- and nineteenth-century divides between “French” and “foreign.” The portraits’ shifting form and function reveal France’s vacillating attitudes towards and ambivalent foreign policies regarding pre-colonial Cochinchina, which were based on an evolving French imagining of this little-known “Other” within the frame of French Empire. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the support and guidance of several individuals. -

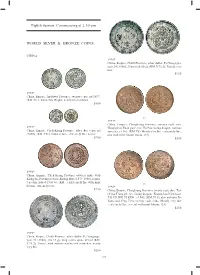

Eighth Session, Commencing at 2.30 Pm WORLD SILVER & BRONZE

Eighth Session, Commencing at 2.30 pm WORLD SILVER & BRONZE COINS CHINA 1996* China, Empire, Chihli Province, silver dollar, Pei Yang type, year 34 (1908), 39mm (26.60 g), (KM.Y.73.3). Toned, very fi ne. $150 1992* China, Empire, An-Hwei Province, twenty cents, nd.1897, (KM.43.1, Kann 50). Bright, nearly uncirculated. $500 part 1997* China, Empire, Chingkiang Province, twenty cash, obv. 1993* 'Kuang-hsu Yuan pao', rev. Hu Poo facing dragon, various China, Empire, Cheh-Kiang Province, silver fi ve cents, nd varieties, c.1903, (KM.Y5). Mostly very fi ne - extremely fi ne, (1898), (KM.Y51). Golden tone, extremely fi ne, scarce. one with mint bloom traces. (15) $200 $200 1994* China, Empire, Cheh-Kiang Province obverse mule with Kiang See Province reverse, Kuang Hsu, (1875-1908), copper ten cash, issued 1903-6), (KM.-). Extremely fi ne with mint part bloom, extremely rare. 1998* $250 China, Empire, Chingkiang Province, twenty cash, obv. 'Tai- ch'ing T'ung pi', rev. facing dragon, 'Kuang-hsu Nien-tsao' TAI CHING TI KUO, c.1905, (KM.Y11), also includes Pei Yang and Feng Tien, twenty cash coins. Mostly very fi ne - extremely fi ne, several with mint bloom. (25) $250 1995* China, Empire, Chihli Province, silver dollar, Pei Yang type, year 34 (1908), (26.44 g), long centre spine of tail (KM. Y.73.2). Toned, with surface marks and scratches, nearly very fi ne. $200 241 1999* 2004* China, Empire, Chingkiang, central mint, Tientsin, under China, Empire, Kirin Province, silver dollar, 1906, 38.5mm, Hsuen Tung (1908-1911), issued in 3rd year (1911), silver (26.37 g), (KM.Y183, Kann 537).