The Significant Other: a Longitudinal Analysis of Significant Samples in Journalism Research, 2000–2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reportfrom the Capital

REPORTfrom the Capital BJC weighs in on proposed faith-based regulations, affirms progress On October 5, the BJC, working with a government funding of “inherently religious broad coalition of dozens of organizations, activities” to prevent government funding of submitted comments on proposed regula- religion, a violation of the First Amendment. tions that would govern partnerships be- This phrase has proved confusing for some tween the government and faith-based social faith-based providers because the services service providers. These regulations from provided (such as operating a food pantry) nine federal agencies demonstrate a move were motivated by religious directives (for toward sound resolution of a church-state example, Matthew 25:35). The proposed reg- conflict that has been bitterly contested for ulations change the terminology to prohibit Magazine of the more than two decades. government funding of “expressly religious Baptist Joint Committee In early August, the Obama administration activities.” Faith-based providers may not took a significant step to strengthen part- use government funding to pay for overtly nerships between the federal government religious activities such as worship, religious Vol. 70 No. 8 and religious organizations that provide instruction or proselytization. The proposed services for those in need. The issuance of the regulatory changes clarify that activities must September/October proposed rule changes is part of a complex be offered at a different time or in a different administrative process that will continue location from any federally funded program- 2015 over the next few months. The breadth of this ming. development, and its potential to provide A second — and arguably the most import- consistency and protect government benefi- ant — improvement is the requirement that INSIDE: ciaries, is welcome news for religious liberty. -

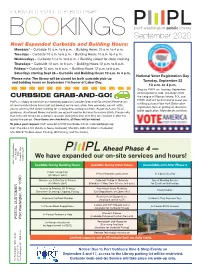

BOOKINGS September 2020 New! Expanded Curbside and Building Hours: Mondays* – Curbside 10 A.M

YOUR MONTHLY GUIDE TO PORT’S LIBRARY BOOKINGS September 2020 New! Expanded Curbside and Building Hours: Mondays* – Curbside 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. • Building Hours 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Tuesdays – Curbside 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. • Building Hours 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Wednesdays – Curbside 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. • Building closed for deep cleaning. Thursdays – Curbside 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. • Building Hours 12 p.m. to 6 p.m. Fridays – Curbside 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. • Building Hours 12 p.m. to 6 p.m. Saturdays starting Sept 26 – Curbside and Building Hours 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. National Voter Registration Day *Please note: The library will be closed for both curbside pick-up and building hours on September 7 in honor of Labor Day. Tuesday, September 22 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Stop by PWPL on Tuesday, September 22 to register to vote. Volunteers from CURBSIDE GRAB-AND-GO! the League of Woman Voters, FOL and PWPL staff will be on hand to assist you PWPL is happy to continue our extremely popular Curbside Grab-and-Go service! Reserve any in filling out your New York State voter of your favorite library items (not just books!) online and, when they are ready, we will notify registration form or getting an absentee you to come by the library building for a contactless pickup out front. As per ALA and OCLC ballot application. More details to follow. guidance, all returned library materials are quarantined for 96 hours to ensure safety. -

Read the Full Report As an Adobe Acrobat

CREATING A PUBLIC SQUARE IN A CHALLENGING MEDIA AGE A White Paper on the Knight Commission Report on Informing Communities: Sustaining Democracy in the Digital Age Norman J. Ornstein with John C. Fortier and Jennifer Marsico Executive Summary Much has changed in media and communications costs. Newspapers would benefit from looser technologies over the past fifty years. Today we face the rules and more flexibility. News organizations dual problems of an increasing gap in access to these should be able to work together to collect technologies between the “haves” and “have nots” and payment for content access. fragmentation of the once-common set of facts that 2. Implement government subsidies. With high Americans shared through similar experiences with the costs of operation, the newspaper industry media. This white paper lays out four major challenges should be eligible for lower postal rates and that the current era poses and proposes ways to meet exemptions from sales taxes. these challenges and boost civic participation. 3. Change the tax status of papers, making them tax-exempt in some fashion. This could Challenge One: Keeping Newspapers Alive involve categorizing newspapers as “bene- fit” or “flexible purpose” corporations, or Until They Are Well treating them as for-profit businesses that have a charitable or educational purpose. A large part of the average newspaper budget com- prises costs related to printing, bundling, and deliv- ery. The development of new delivery models could greatly reduce (or perhaps eliminate) these Challenge Two: Universal Access and expenses. Potential new models use screen- Adequate Spectrum technology advancement (using new tools like the iPad) and raise subscription revenue online. -

And the Masonic Family of Idaho

The Freemasons and the Masonic Family of Idaho Grand Lodge of Ancient Free and Accepted Masons of Idaho 219 N. 17th St., Boise, ID 83702 US Tel: +1-208-343-4562 Fax: +1 208-343-5056 Email: [email protected] Web: www.idahomasons.org First Printing: June 2015 online 1 | Page Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Attraction of Freemasonry ............................................................................................................................ 5 What they say about Freemasonry.... ........................................................................................................... 6 Grand Lodge of Idaho Territory ‐ The Beginning .......................................................................................... 7 Freemasons and Charity ............................................................................................................................... 9 Our Mission: .............................................................................................................................................. 9 Child Identification Program: .................................................................................................................... 9 Bikes for Books .......................................................................................................................................... 9 Organization Information ........................................................................................................................ -

Journalist Lowell Mellett

Working for Goodwill: Journalist Lowell Mellett (long version) by Mordecai Lee University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Note: This paper is an extended version of “Working for Goodwill: Journalist Lowell Mellett,” published in Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History (quarterly of the Indiana Historical Society) 27:4 (Fall 2015) 46-55. (All copyright protections of the article apply to this longer version.) This revision contains additional text, about twice as much as in the article. It also contains references and endnotes, which the journal’s house style omits. In addition, a chronological bibliography of Mellett’s non-newspaper writings has been added at the end of the article. Abstract: Lowell Mellett was a major figure in President Franklin Roosevelt’s unprecedented communications apparatus. He is largely remembered for his role as liaison between the federal government and Hollywood during World War II. However, Mellett had a major career in journalism before joining the administration in 1938 and was an influential syndicated columnist after leaving the White House in 1944. As his pre- and post-White House service is less known, this article seeks to provide an historical sketch of his journalism career. Presidential assistant Lowell Mellett (1884-1960) looms relatively large in one aspect of the history of Franklin Roosevelt’s administration and World War II. He was the senior federal 1 liaison between the film industry and Washington during the early years of the war. Holding a series of changing titles, he was President Roosevelt’s point man for the Hollywood studios, working to promote productions that supported FDR’s internationalist orientation and the nation’s war goals. -

Teaching and Learning in a Microelectronic Age. INSTITUTION Phi Delta Kappa Educational Foundation, Bloomington, Ind

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 281 487 fk 012 601 AUTHOR Shane, Harold G. TITLE Teaching and Learning in a Microelectronic Age. INSTITUTION Phi Delta Kappa Educational Foundation, Bloomington, Ind. REPORT NO ISBN-0-87367-434-0 PUB DATE 87 NOTE 96p. AVAILABLE FROMPhi Delta Kappa, PO Box 789, Bloomington, IN 47402 ($4,00). puB TYPE Books (010) -- Information Analyses (070) -- Viewpoints (120) EDRS_PRICE_ MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Change Strategies; Computers; *Computer Uses in Education; Curriculum Development; *Educational Change; Global Approach; Mass Media Effects; Robotics; *Science and Society; *Technological Advancement; Television Research IDENTIFIERS Learning Environment; *Microelectronics ABSTRACT General background information on microtechnologies with_ implications for educators provides an introduction to this review of past and current developments in microelectronics and specific ways in which the microchip is permeating society, creating problems and opportunities both in the workplace and the home. Topics discussed in the first of two major sections of this report include educational and industrial impacts of the computer and peripheral equipment, with particular attention to the use of computers in educational institutions and in an information society; theuse of robotics, a technology now being used in more than 2,000 schools and 1,200 colleges; the growing power of the media, particularly television; and the importance of educating young learners tocope with sex, violence, and bias in the media. The second section addresses issues created by microtechnologies since the first computer made its debut in 1946; redesigning the American educational system for a high-tech society; and developing curriculum appropriate for the microelectronic age, including computer applications and changes at all levels from early childhood education to programs for mature learners. -

The Studio Museum in Harlem Magazine Summer/Fall 2012 Studio Magazine Board of Trustees This Issue of Studio Is Underwritten, Editor-In-Chief Raymond J

The Studio Museum in Harlem Magazine Summer/Fall 2012 Studio Magazine Board Of Trustees This issue of Studio is underwritten, Editor-in-Chief Raymond J. McGuire, Chairman in part, with support from Bloomberg Elizabeth Gwinn Carol Sutton Lewis, Vice-Chair Creative Director Rodney M. Miller, Treasurer The Studio Museum in Harlem is supported, Thelma Golden in part, with public funds provided by Teri Trotter, Secretary Managing Editor the following government agencies and elected representatives: Dominic Hackley Jacqueline L. Bradley Valentino D. Carlotti Contributing Editors The New York City Department of Kathryn C. Chenault Lauren Haynes, Thomas J. Lax, Cultural A"airs; New York State Council Joan Davidson Naima J. Keith on the Arts, a state agency; National Gordon J. Davis Endowment for the Arts; Assemblyman Copy Editor Reginald E. Davis Keith L. T. Wright, 70th A.D. ; The City Samir Patel Susan Fales-Hill of New York; Council Member Inez E. Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Dickens, 9th Council District, Speaker Design Sandra Grymes Christine Quinn and the New York City Pentagram Joyce K. Haupt Council; and Manhattan Borough Printing Arthur J. Humphrey, Jr. President Scott M. Stringer. Finlay Printing George L. Knox !inlay.com Nancy L. Lane Dr. Michael L. Lomax The Studio Museum in Harlem is deeply Original Design Concept Tracy Maitland grateful to the following institutional 2X4, Inc. Dr. Amelia Ogunlesi donors for their leadership support: Corine Pettey Studio is published two times a year Bloomberg Philanthropies Ann Tenenbaum by The Studio Museum in Harlem, Doris Duke Charitable Foundation John T. Thompson 144 W. 125th St., New York, NY 10027. -

Oral History Interview with Sharon Huntley Kahn, July 10, 2018

Archives and Special Collections Mansfield Library, University of Montana Missoula MT 59812-9936 Email: [email protected] Telephone: (406) 243-2053 This transcript represents the nearly verbatim record of an unrehearsed interview. Please bear in mind that you are reading the spoken word rather than the written word. Oral History Number: 463-001 Interviewee: Sharon Huntley Kahn Interviewer: Donna McCrea Date of Interview: July 10, 2018 Donna McCrea: This is Donna McCrea, Head of Archives and Special Collections at the University of Montana. Today is July 10th of 2018. Today I'm interviewing Sharon Huntley Kahn about her father Chet Huntley. I'll note that the focus of the interview will really be on things that you know about Chet Huntley that other people would maybe not have known: things that have not been made public already or don't appear in many of the biographical materials and articles about him. Also, I'm hoping that you'll share some stories that you have about him and his life. So I'm going to begin by saying I know that you grew up in Los Angeles. Can you maybe start there and talk about your memories about your father and your time in L.A.? Sharon Kahn: Yes, Donna. Before we begin, I just want to say how nice it is to work with you. From the beginning our first phone conversations, I think at least a year and a half ago, you've always been so welcoming and interested, and it's wonderful to be here and I'm really happy to share inside stories with you. -

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1957 A Rhetorical Study of the Gubernatorial Speaking of Franklin D. Roosevelt. Paul Jordan Pennington Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Pennington, Paul Jordan, "A Rhetorical Study of the Gubernatorial Speaking of Franklin D. Roosevelt." (1957). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 222. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/222 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A RHETORICAL STUD* OP THE GUBERNATORIAL SPEAKING OP FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Meohanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Speech by Paul Jordan Pennington B. A., Henderson State Teachers College, 19U8 M. A., Oklahoma University, 1950 August, 1957 ACKNOWLEDGMENT The writer wishes to acknowledge the inspiration, guidance, and continuous supervision of Dr. Waldo W. Braden, Professor of Speech at Louisiana State University. As the writer1s major advisor, he has given generously of his time, his efforts, and his sound advice. Dr. Braden is in no way responsible for any errors or short-comings of this study, but his suggestions are largely responsible for any merits it may possess. Dr. C. M. Wise, Head of the Department of Speech, and Dr. -

Call for Strike Fails As Polish Arrests Widen WARSAW, Poland (AP) -Factoriesin War- Factories Throughout the Country

Monday Church dedicated Special yule Giants remain Specials in Ocean, page 5 series, page 8 alive: Sports The Daily Monmouth County's Great Home Newspaper VOL. 104 NO. 145 SHREWSBURY, N.J. MONDAY, DECEMBER 14, 1981 25 CENTS Call for strike fails as Polish arrests widen WARSAW, Poland (AP) -Factoriesin War- factories throughout the country. "If the work- saw were operating today despite a call by ers go to their work places on Monday, there Solidarity militants for a general strike in re- will be occupations or a general strike," said taliation for the Communist government's Stefan A. Trzclnski, deputy press spokesman for crackdown on the Independent labor movement. the big Warsaw local. Initial checks of large factories in some But Poland's Roman Catholic primate, districts of the capital found no strikes or pro- Archbishop Josef Glemp, appealed to the work- tests by members of the temporarily suspended ers In a broadcast sermon: "Do not start a fight union, many of whose leaders were seized Sun- between Poles. Do not give your lives away." day when the government imposed martial law. There was no information immediately available on the situation outside the Warsaw Western leaders doubt area. Solidarity sources said as many as 3,000 Russia will move, page 2 members of the union may have been rounded NEW YORK POLISH RALLY — People from the Polish American in front of the Polish consulate in Manhattan yesterday. They are up in the capital alone. Earlier estimates put the Congress and the Social Democrats, U.S.A., organizations march supporting the Solidarity movement in Poland. -

Journalism 375/Communication 372 the Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture

JOURNALISM 375/COMMUNICATION 372 THE IMAGE OF THE JOURNALIST IN POPULAR CULTURE Journalism 375/Communication 372 Four Units – Tuesday-Thursday – 3:30 to 6 p.m. THH 301 – 47080R – Fall, 2000 JOUR 375/COMM 372 SYLLABUS – 2-2-2 © Joe Saltzman, 2000 JOURNALISM 375/COMMUNICATION 372 SYLLABUS THE IMAGE OF THE JOURNALIST IN POPULAR CULTURE Fall, 2000 – Tuesday-Thursday – 3:30 to 6 p.m. – THH 301 When did the men and women working for this nation’s media turn from good guys to bad guys in the eyes of the American public? When did the rascals of “The Front Page” turn into the scoundrels of “Absence of Malice”? Why did reporters stop being heroes played by Clark Gable, Bette Davis and Cary Grant and become bit actors playing rogues dogging at the heels of Bruce Willis and Goldie Hawn? It all happened in the dark as people watched movies and sat at home listening to radio and watching television. “The Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture” explores the continuing, evolving relationship between the American people and their media. It investigates the conflicting images of reporters in movies and television and demonstrates, decade by decade, their impact on the American public’s perception of newsgatherers in the 20th century. The class shows how it happened first on the big screen, then on the small screens in homes across the country. The class investigates the image of the cinematic newsgatherer from silent films to the 1990s, from Hildy Johnson of “The Front Page” and Charles Foster Kane of “Citizen Kane” to Jane Craig in “Broadcast News.” The reporter as the perfect movie hero. -

" WE CAN NOW PROJECT..." ELECTION NIGHT in AMERICA By. Sean P Mccracken "CBS NEWS Now Projects...NBC NEWS Is Read

" WE CAN NOW PROJECT..." ELECTION NIGHT IN AMERICA By. Sean P McCracken "CBS NEWS now projects...NBC NEWS is ready to declare ...ABC NEWS is now making a call in....CNN now estimates...declares...projects....calls...predicts...retracts..." We hear these few opening words and wait on the edges of our seats as the names and places which follow these familiar predicates make very well be those which tell us in the United States who will occupy the White House for the next four years. We hear the words, follow the talking-heads and read the ever changing scripts which scroll, flash or blink across our television screens. It is a ritual that has been repeated an-masse every four years since 1952...and for a select few, 1948. Since its earliest days, television has had a love affair with politics, albeit sometimes a strained one. From the first primitive experiments at the Republican National Convention in 1940, to the multi angled, figure laden, information over-loaded spectacles of today, the "happening" that unfolds every four years on the second Tuesday in November, known as "Election Night" still holds a special place in either our heart...or guts. Somehow, it still manages to keep us glued to our television for hours on end. This one night that rolls around every four years has "grown up" with many of us over the last 64 years. Staring off as little more than chalk boards, name plates and radio announcers plopped in front of large, monochromatic cameras that barely sent signals beyond the limits of New York City and gradually morphing into color-laden, graphic-filled, information packed, multi channel marathons that can be seen by virtually...and virtually seen by...almost any human on the planet.