Early Spring by Guo Xi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chinese Culture University, Taipei, Taiwan

International Association for Intercultural Communication Studies July 6-8, 2005 Chinese Culture University, Taipei, Taiwan [English Part] Conference Co-Directors Yung-Yi Tang, Chinese Culture University, Taiwan Guo-Ming Chen, University of Rhode Island, USA Staff Assistance to the Program: Tong Yu, Joanne Mundorf, & Christine Egan, University of Rhode Island Wednesday, July 6 Plenary I Wednesday 8:30-9:00 a.m. Auditorium Welcome Ceremony Speaker: Professor Tian-Ren Lee (CCU President) Introduction: 101 Wednesday 9:15-10:45 a.m. Room A Communication Competence in Different Cultural Contexts Chair: Hairong Feng, Purdue University, USA “Intercultural Competence of U.S. Expatriates in Singapore.” Rosemary Chai, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore “Developing Methods for Teaching Communicative Competence Based on the Job Interview Speech Event.” Victoria Orange, Connecting Cultures Ltd, France “Intercultural Sensitivity of Spanish Teenagers: A Diagnostic and Study about Educational Necessities.” Ruth Vila Banos, University of Barcelona, Spain “Arabic (Islamic) Greetings in the Indian Community: A Cross-Cultural Study.” Abdul Wahid Qasem Ghaleb, Sanaa University, Yemen Republic “Hide Your Thumbs.” Charles McHugh, Setsunan University, Japan Respondent: Teruyuki Kume, Rikkyo University, Japan 102 Wednesday 9:15-10:45 a.m. Room B Issues in Rhetorical Communication Chair: Yoshitaka Miike, University of Hawai‘i at Hilo, USA “Ethnographic Fiction.” Lyall Crawford, Tzu Chi University, Taiwan “The Reinforcement of Opposition.” Maritza Castillo, Tampa, Florida, USA 2 “From Mutual Incomprehension toward Mutual Recognition.” Gu, Li, University of Masschueete-Amherst, USA “Structural Features of Arguments in Spoken Japanese: Comparing Superior and Advanced Learners.” Shinobu Suzuki, Hokkaido University, Japan Respondent: Sean Tierney, Division of Communications, Miles College, USA 103 Wednesday 9:15-10:45 a.m. -

![[Re]Viewing the Chinese Landscape: Imaging the Body [In]Visible in Shanshuihua 山水畫](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1753/re-viewing-the-chinese-landscape-imaging-the-body-in-visible-in-shanshuihua-1061753.webp)

[Re]Viewing the Chinese Landscape: Imaging the Body [In]Visible in Shanshuihua 山水畫

[Re]viewing the Chinese Landscape: Imaging the Body [In]visible in Shanshuihua 山水畫 Lim Chye Hong 林彩鳳 A thesis submitted to the University of New South Wales in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Chinese Studies School of Languages and Linguistics Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of New South Wales Australia abstract This thesis, titled '[Re]viewing the Chinese Landscape: Imaging the Body [In]visible in Shanshuihua 山水畫,' examines shanshuihua as a 'theoretical object' through the intervention of the present. In doing so, the study uses the body as an emblem for going beyond the surface appearance of a shanshuihua. This new strategy for interpreting shanshuihua proposes a 'Chinese' way of situating bodily consciousness. Thus, this study is not about shanshuihua in a general sense. Instead, it focuses on the emergence and codification of shanshuihua in the tenth and eleventh centuries with particular emphasis on the cultural construction of landscape via the agency of the body. On one level the thesis is a comprehensive study of the ideas of the body in shanshuihua, and on another it is a review of shanshuihua through situating bodily consciousness. The approach is not an abstract search for meaning but, rather, is empirically anchored within a heuristic and phenomenological framework. This framework utilises primary and secondary sources on art history and theory, sinology, medical and intellectual history, ii Chinese philosophy, phenomenology, human geography, cultural studies, and selected landscape texts. This study argues that shanshuihua needs to be understood and read not just as an image but also as a creative transformative process that is inevitably bound up with the body. -

Philosophy and Aesthetics of Chinese Landscape Painting Applied to Contemporary Western Film and Digital Visualisation Practice

Practice as Research: Philosophy and Aesthetics of Chinese Landscape Painting Applied to Contemporary Western Film and Digital Visualisation Practice Christin Bolewski Loughborough School of Art and Design, Leicestershire, UK, LE11 3TU Abstract. This practice-led research project investigates how East Asian Art traditions can be understood through reference to the condition of Western con- temporary visual culture. Proceeding from Chinese thought and aesthetics the traditional concept of landscape painting ‘Shan-Shui-Hua’ is recreated within the new Western genre of the ‘video-painting’. The main features of the tradi- tional Chinese landscape painting merges with Western moving image practice creating new modes of ‘transcultural art’ - a crossover of Western and Asian aesthetics - to explore form, and questions digital visualisation practice that aims to represent realistic space. Confronting the tools of modern computer visualisation with the East Asian concept creates an artistic artefact contrasting, confronting and counterpointing both positions. 1 Introduction This paper is based on a practice-led Fine Art research project and includes the dem- onstration of video art. It presents an explorative art project and explains how the visual and the verbal are unified in this artistic research. It investigates how East Asian art traditions can be understood through reference to the condition of Western contemporary visual culture. Proceeding from Chinese thought and aesthetics the traditional concept of landscape painting ‘Shan-Shui-Hua’ is recreated within the new genre of the ‘video-painting’ as a single (flat) screen video installation. The main features of the traditional Chinese landscape painting merges with Western moving image practice creating new modes of ‘transcultural art’ - a crossover of Western and Asian aesthetics - to explore form, and questions digital visualisation practice that aims to represent realistic space. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 469 Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Art Studies: Science, Experience, Education (ICASSEE 2020) "Evaluating Painters All Over the Country" Guo Xi and His Landscape Painting Min Ma1,* 1Academy of Arts & Design, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Styled Chunfu, Guo Xi was a native of Wenxian County. In the beginning, he learned from the methods of Li Cheng, yet he was rather good at expressing his own feelings, thus becoming adept at surpassing his master and creating a main school of the royal court landscape painting in the Northern Song Dynasty whose influence had lasted to later ages. Linquan Gaozhi Ji, Guo Xi's well-known theory on landscape painting, was a book emerged after the art of landscape painting in the became highly mature in the Northern Song Dynasty, which was an unprecedented peak in landscape painting and a rich treasure house in the history of landscape painting. Keywords: Guo Xi, Linquan Gaozhi, landscape painting Linquan Gaozhi Ji wrote by Guo Xi and his son I. INTRODUCTION Guo Si in 1080 was a classic book on landscape Great progress had been made in the creation of painting as the art of landscape painting became highly panoramic landscape paintings in China during the mature in the Northern Song Dynasty. The book was Northern Song Dynasty, after the innovations of Jing written in the late Northern Song Dynasty, when the art Hao, Guan Tong, Dong Yuan and Ju Ran, when a of landscape painting in China had already entered a number of influential landscape painters and exquisite relatively mature stage. -

The Donkey Rider As Icon: Li Cheng and Early Chinese Landscape Painting Author(S): Peter C

The Donkey Rider as Icon: Li Cheng and Early Chinese Landscape Painting Author(s): Peter C. Sturman Source: Artibus Asiae, Vol. 55, No. 1/2 (1995), pp. 43-97 Published by: Artibus Asiae Publishers Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3249762 . Accessed: 05/08/2011 12:40 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Artibus Asiae Publishers is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Artibus Asiae. http://www.jstor.org PETER C. STURMAN THE DONKEY RIDER AS ICON: LI CHENG AND EARLY CHINESE LANDSCAPE PAINTING* he countryis broken,mountains and rivers With thesefamous words that lamentthe "T remain."'I 1T catastropheof the An LushanRebellion, the poet Du Fu (712-70) reflectedupon a fundamental principle in China:dynasties may come and go, but landscapeis eternal.It is a principleaffirmed with remarkablepower in the paintingsthat emergedfrom the rubbleof Du Fu'sdynasty some two hundredyears later. I speakof the magnificentscrolls of the tenth and eleventhcenturies belonging to the relativelytightly circumscribedtradition from Jing Hao (activeca. 875-925)to Guo Xi (ca. Ooo-9go)known todayas monumentallandscape painting. The landscapeis presentedas timeless. We lose ourselvesin the believabilityof its images,accept them as less the productof humanminds and handsthan as the recordof a greatertruth. -

Art in Translation Programme

Art and Translation Taiwan, Hong Kong and Korea University of Edinburgh 28-29 October 2017 Free Admissions Please RSVP by 25 Oct with Dr Li-Heng Hsu ([email protected] ) Taiwan Academy Lecture 1| From The Concept of Social sculpture to the Public Art in Taiwan: My Artistic Journey 從社會雕塑到台灣公共藝術: 我的藝術歷程 Speaker | Ma-Li Wu, Artist & Professor Chair | Marko Daniel, Tate Modern Date | Saturday, 28 October 2017 10:00 – 12:00 Venue | The West Court Lecture Theatre, ECA Main Building, University of Edinburgh 74 Lauriston Place, Edinburgh EH3 9DF Mali Wu developed an interest in socially-engaged practice and started to make installations and objects that deal with historical narratives. Since 2000 she has been producing community- based projects such as Awake in Your Skin, 2000 – 2004 a collaboration with the Taipei Awakening Association, a feminist movement in Taiwan that uses fabric to explore the texture of women’s lives. In By the River, on the River, of the River, 2006, she worked with several community universities tracing the four rivers that surround Taipei. With the help of the county government she invited over 30 artists to reside in 20 villages and together they attempted to shape a learning community through art, the project Art as Environment—A Cultural Action on Tropic of Cancer, made between 2005-2007 in Chiayi County made a significant impact on local cultural policy and inspired people to consider different ways to activate community building. It also resulted in a series of conferences and dialogues organised by NGOs. In 2008, Mali Wu unveiled “Taipei Tomorrow As Lake Again”, a garden installation alongside the Taipei Fine Arts Museum that visitors were invited to harvest. -

Shan-Shui-Hua’ – Traditional Chinese Landscape Painting Reinterpreted As Moving Digital Visualisation

‘SHAN-SHUI-HUA’ – TRADITIONAL CHINESE LANDSCAPE PAINTING REINTERPRETED AS MOVING DIGITAL VISUALISATION Christin Bolewski Loughborough School of Art and Design Loughborough, UK, LE11 3TU [email protected] Abstract – This paper is based on a practice-led research project and includes the demonstration of video art. It investigates how East Asian traditions of landscape art can be understood through reference to the condition of Western contemporary visual culture. Proceeding from Chinese thought and aesthetics the traditional concept of landscape painting ‘Shan-Shui-Hua’ is recreated in modern digital visualisation practice to explore form and question linear perspective that aims to represent realistic space. PERSPECTIVE AND TEMPORALITY IN TRADITIONAL CHINESE LANDSCAPE PAINTING The intended purpose and motivation of science and technological progress in our Western civilisation is mainly directed by achieving perfection in measuring and rendering the objective and accountable ‘truth’ of our world. With regard to the history of the development of visualisation tools this has continuously led towards the invention of hardware and software whose success is measured by its potential to render a more perfect representational image. The creation of real or hyper-real space is one of the main objectives in film and 3D visualisation practice. Based on the Renaissance tradition, achieving the effect of realistic space by the employment of linear perspective is a major preoccupation of Western visual culture. In the construction of a virtual 3D space the Cartesian grid is used to reconstruct this geometrical perspective, whereas Eastern culture has a concept of using multiple vanishing points that within which the creation of a realistic space is not one of its aims. -

2013 Editor Lindsay Shen, Phd

Journal of the royal asiatic society china Vol. 75 no. 1, 2013 Editor Lindsay Shen, PhD. Copyright 2013 RAS China. The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society China is published by Earnshaw Books on behalf of the Royal Asiatic Society China. Contributions The editors of the Journal invite submission of original unpublished scholarly articles and book reviews on the religion and philosophy, art and architecture, archaeology, anthropology and environment, of China. Books sent for review will be donated to the Royal Asiatic Society China Library. Contributors receive a copy of the Journal. Subscriptions Members receive a copy of the journal, with their paid annual membership fee. Individual copies will be sold to non-members, as available. Library Policy Copies and back issues of the Journal are available in the library. The library is available to members. www.royalasiaticsociety.org.cn Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society China Vol. 75 No. 1, 2013 978-988-8422-44-9 © 2013 Royal Asiatic Society China The copyright of each article rests with the author. EB086 Designed and produced for RAS China by Earnshaw Books Ltd. (Hong Kong) Room 1801, 18F, Public Bank Centre, 120 Des Voeux Road Central, Hong Kong All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in material form, by any means, whether graphic, electronic, mechanical or other, including photocopying or information storage, in whole or in part. May not be used to prepare other publications without written permission from the publisher. The Royal Asiatic Society China thanks Earnshaw -

Teachers' Guide for Painting

Painting TO THE TEACHER OBJECTIVES OF THIS UNIT: To introduce students to one of the major Chinese arts. To raise questions about what we can infer from paintings about social and material life. To introduce the distinction between court and scholar painting and allow discussion of the emergence of landscape as a major art form. TEACHING STRATEGIES: This unit can be taught as a general introduction to Chinese painting or the two main subsections can be taught independently, depending on whether the teacher is more interested in using painting to teach about other things or wants to discuss painting itself as an art. WHEN TO TEACH: In a chronologically-organized course, Painting should not be used before the Song period, as most of the examples in this unit are from the Song and Yuan dynasties. If both Calligraphy and Painting are used, Calligraphy should precede Painting, as it provides valuable information on social and aesthetic values which informed the study, evaluation, and collecting of both types of works of art. This unit would also be appropriate in a course on Chinese art. http://depts.washington.edu/chinaciv/painting/tptgintr.htm (1 of 3) [11/26/2001 10:59:00 AM] Painting We know from textual and archaeological sources that painting was practiced in China from very early times and in a variety of media. Wall paintings were produced in great numbers in the early period of China's history, but because so little early architecture in China remained intact over the centuries, few of these large-scale paintings have survived. -

The Role of Landscape Art in Cultural and National Identity: Chinese and European Comparisons

sustainability Article The Role of Landscape Art in Cultural and National Identity: Chinese and European Comparisons Xiaojing Wen 1,* and Paul White 2 1 School of Design, Shanghai Jiaotong University, Shanghai 200240, China 2 Department of Geography, University of Sheffield, Sheffield S10 2TG, UK; P.White@sheffield.ac.uk * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 5 June 2020; Accepted: 3 July 2020; Published: 7 July 2020 Abstract: The depiction of landscape in art has played a major role in the creation of cultural identities in both China and Europe. Landscape depiction has a history of over 1000 years in China, whilst in Europe its evolution has been more recent. Landscape art (shan shui) has remained a constant feature of Chinese culture and has changed little in style and purpose since the Song dynasty. In Europe, landscape depictions have been significant in the modern determination of cultural and national identities and have served to educate consumers about their country. Consideration is given here to Holland, England, Norway, Finland and China, demonstrating how landscape depictions served to support a certain definition of Chinese culture but have played little political role there, whilst in Europe landscape art has been produced in a variety of contexts, including providing support for nationalism and the determination of national identity. Keywords: landscape art; Chinese landscapes; European landscapes; cultural identity; national identity 1. Introduction The concept of cultural identity commonly refers to a feeling of belonging to a group in which there are a number of shared attributes which might include, among other things, knowledge, beliefs, artefacts, arts, morals, and law. -

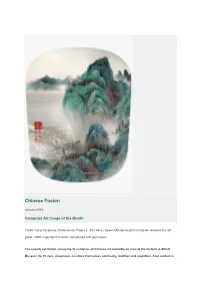

Chinese Fusion

Chinese Fusion January 2014 Computer Art Image of the Month Credit: Yang Yongliang, Viridescence, Pages 2, 44 x 44cm, Epson Ultragiclee print on Epson textured fine art paper, 2009. Copyright the artist, reproduced with permission. The superb exhibition surveying 12 centuries of Chinese art currently on view at the Victoria & Albert Museum (to 19 Jan), showcases a culture that values continuity, tradition and repetition. Also evident is the strong history within Chinese art of honouring the artistic achievements of the preceding generation through the deliberate mimicking of previous styles of painting. The Shanghai-based Yang Yongliang, our featured artist this month, does exactly this but gives a contemporary interpretation to his traditionally-inspired art, utilising new technology and updated imagery. A fusion of the old with new modalities from the West creates something entirely new in art. Yang Yongliang cleverly recreates the main principles of Chinese blue-green Shan shui (‘mountain and water’) paintings which first arose in the fifth century using mineral dyes for the vibrant hues. Shan shui works are painted and designed according to elemental theory with the five elements representing various parts of the natural world. Yang uses a camera and computer to manipulate his imagery of urban life thus subtly subverting traditional painting. In place of the historic natural landscapes filled with rock formations and craggy trees - perhaps even a contemplative scholar - in Yang’s work we see construction sites, large cranes, fly-overs and the assorted detritus of the rapidly growing, increasingly urbanised country that is contemporary China. The dreamlike Shan shui seamlessly morphs into shocking modernity. -

Shan Shui 2010: H20 Christopher Phillips This Exhibition Marks The

Shan Shui 2010: H20 Christopher Phillips This exhibition marks the second installment of the Green Art Project launched by BCA director Weng Ling in 2009 with the exhibition “Shan Shui: Nature on the Horizon of Art”. By using contemporary art works as a focal point, the Green Art Project aims to stimulate discussion of the ways that humankind can move toward a sustainable balance between the natural environment and the needs of human society. The current exhibition, “Shan Shui 2010: H2O”, presents video works by four highly accomplished contemporary artists: Song Dong, Bill Viola, Wang Gongxin, and Janaina Tschäpe. Although these works are visually and conceptually quite distinct, what unites them is the fact that they all highlight a single, unique substance--water--which is an inescapable element of human existence. Water is both in us and around us. Making up more than half of the physical composition of the human body, it is essential for human survival. At the same time, water covers more than 70 percent of the earth's surface. Perhaps the most remarkable characteristic of water is that it is a substance without a fixed form. It can appear as rain, mist, fog, dew, clouds, ice, sleet, snow, and hail, and as such larger natural formations as oceans, lakes, rivers, and waterfalls. Because it has long been recognized as a symbol of all that is changeable and fleeting in nature, water has fascinated countless artists who have a special feeling for the natural world. By presenting this selection of contemporary artworks that imaginatively probe the meaning of water's constant presence in human life, “Shan Shui 2010: H2O”also aims to raise awareness of one of the most urgent environmental issues of the present day.