Shan Shui 2010: H20 Christopher Phillips This Exhibition Marks The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chinese Culture University, Taipei, Taiwan

International Association for Intercultural Communication Studies July 6-8, 2005 Chinese Culture University, Taipei, Taiwan [English Part] Conference Co-Directors Yung-Yi Tang, Chinese Culture University, Taiwan Guo-Ming Chen, University of Rhode Island, USA Staff Assistance to the Program: Tong Yu, Joanne Mundorf, & Christine Egan, University of Rhode Island Wednesday, July 6 Plenary I Wednesday 8:30-9:00 a.m. Auditorium Welcome Ceremony Speaker: Professor Tian-Ren Lee (CCU President) Introduction: 101 Wednesday 9:15-10:45 a.m. Room A Communication Competence in Different Cultural Contexts Chair: Hairong Feng, Purdue University, USA “Intercultural Competence of U.S. Expatriates in Singapore.” Rosemary Chai, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore “Developing Methods for Teaching Communicative Competence Based on the Job Interview Speech Event.” Victoria Orange, Connecting Cultures Ltd, France “Intercultural Sensitivity of Spanish Teenagers: A Diagnostic and Study about Educational Necessities.” Ruth Vila Banos, University of Barcelona, Spain “Arabic (Islamic) Greetings in the Indian Community: A Cross-Cultural Study.” Abdul Wahid Qasem Ghaleb, Sanaa University, Yemen Republic “Hide Your Thumbs.” Charles McHugh, Setsunan University, Japan Respondent: Teruyuki Kume, Rikkyo University, Japan 102 Wednesday 9:15-10:45 a.m. Room B Issues in Rhetorical Communication Chair: Yoshitaka Miike, University of Hawai‘i at Hilo, USA “Ethnographic Fiction.” Lyall Crawford, Tzu Chi University, Taiwan “The Reinforcement of Opposition.” Maritza Castillo, Tampa, Florida, USA 2 “From Mutual Incomprehension toward Mutual Recognition.” Gu, Li, University of Masschueete-Amherst, USA “Structural Features of Arguments in Spoken Japanese: Comparing Superior and Advanced Learners.” Shinobu Suzuki, Hokkaido University, Japan Respondent: Sean Tierney, Division of Communications, Miles College, USA 103 Wednesday 9:15-10:45 a.m. -

![[Re]Viewing the Chinese Landscape: Imaging the Body [In]Visible in Shanshuihua 山水畫](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1753/re-viewing-the-chinese-landscape-imaging-the-body-in-visible-in-shanshuihua-1061753.webp)

[Re]Viewing the Chinese Landscape: Imaging the Body [In]Visible in Shanshuihua 山水畫

[Re]viewing the Chinese Landscape: Imaging the Body [In]visible in Shanshuihua 山水畫 Lim Chye Hong 林彩鳳 A thesis submitted to the University of New South Wales in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Chinese Studies School of Languages and Linguistics Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of New South Wales Australia abstract This thesis, titled '[Re]viewing the Chinese Landscape: Imaging the Body [In]visible in Shanshuihua 山水畫,' examines shanshuihua as a 'theoretical object' through the intervention of the present. In doing so, the study uses the body as an emblem for going beyond the surface appearance of a shanshuihua. This new strategy for interpreting shanshuihua proposes a 'Chinese' way of situating bodily consciousness. Thus, this study is not about shanshuihua in a general sense. Instead, it focuses on the emergence and codification of shanshuihua in the tenth and eleventh centuries with particular emphasis on the cultural construction of landscape via the agency of the body. On one level the thesis is a comprehensive study of the ideas of the body in shanshuihua, and on another it is a review of shanshuihua through situating bodily consciousness. The approach is not an abstract search for meaning but, rather, is empirically anchored within a heuristic and phenomenological framework. This framework utilises primary and secondary sources on art history and theory, sinology, medical and intellectual history, ii Chinese philosophy, phenomenology, human geography, cultural studies, and selected landscape texts. This study argues that shanshuihua needs to be understood and read not just as an image but also as a creative transformative process that is inevitably bound up with the body. -

Philosophy and Aesthetics of Chinese Landscape Painting Applied to Contemporary Western Film and Digital Visualisation Practice

Practice as Research: Philosophy and Aesthetics of Chinese Landscape Painting Applied to Contemporary Western Film and Digital Visualisation Practice Christin Bolewski Loughborough School of Art and Design, Leicestershire, UK, LE11 3TU Abstract. This practice-led research project investigates how East Asian Art traditions can be understood through reference to the condition of Western con- temporary visual culture. Proceeding from Chinese thought and aesthetics the traditional concept of landscape painting ‘Shan-Shui-Hua’ is recreated within the new Western genre of the ‘video-painting’. The main features of the tradi- tional Chinese landscape painting merges with Western moving image practice creating new modes of ‘transcultural art’ - a crossover of Western and Asian aesthetics - to explore form, and questions digital visualisation practice that aims to represent realistic space. Confronting the tools of modern computer visualisation with the East Asian concept creates an artistic artefact contrasting, confronting and counterpointing both positions. 1 Introduction This paper is based on a practice-led Fine Art research project and includes the dem- onstration of video art. It presents an explorative art project and explains how the visual and the verbal are unified in this artistic research. It investigates how East Asian art traditions can be understood through reference to the condition of Western contemporary visual culture. Proceeding from Chinese thought and aesthetics the traditional concept of landscape painting ‘Shan-Shui-Hua’ is recreated within the new genre of the ‘video-painting’ as a single (flat) screen video installation. The main features of the traditional Chinese landscape painting merges with Western moving image practice creating new modes of ‘transcultural art’ - a crossover of Western and Asian aesthetics - to explore form, and questions digital visualisation practice that aims to represent realistic space. -

Art in Translation Programme

Art and Translation Taiwan, Hong Kong and Korea University of Edinburgh 28-29 October 2017 Free Admissions Please RSVP by 25 Oct with Dr Li-Heng Hsu ([email protected] ) Taiwan Academy Lecture 1| From The Concept of Social sculpture to the Public Art in Taiwan: My Artistic Journey 從社會雕塑到台灣公共藝術: 我的藝術歷程 Speaker | Ma-Li Wu, Artist & Professor Chair | Marko Daniel, Tate Modern Date | Saturday, 28 October 2017 10:00 – 12:00 Venue | The West Court Lecture Theatre, ECA Main Building, University of Edinburgh 74 Lauriston Place, Edinburgh EH3 9DF Mali Wu developed an interest in socially-engaged practice and started to make installations and objects that deal with historical narratives. Since 2000 she has been producing community- based projects such as Awake in Your Skin, 2000 – 2004 a collaboration with the Taipei Awakening Association, a feminist movement in Taiwan that uses fabric to explore the texture of women’s lives. In By the River, on the River, of the River, 2006, she worked with several community universities tracing the four rivers that surround Taipei. With the help of the county government she invited over 30 artists to reside in 20 villages and together they attempted to shape a learning community through art, the project Art as Environment—A Cultural Action on Tropic of Cancer, made between 2005-2007 in Chiayi County made a significant impact on local cultural policy and inspired people to consider different ways to activate community building. It also resulted in a series of conferences and dialogues organised by NGOs. In 2008, Mali Wu unveiled “Taipei Tomorrow As Lake Again”, a garden installation alongside the Taipei Fine Arts Museum that visitors were invited to harvest. -

Shan-Shui-Hua’ – Traditional Chinese Landscape Painting Reinterpreted As Moving Digital Visualisation

‘SHAN-SHUI-HUA’ – TRADITIONAL CHINESE LANDSCAPE PAINTING REINTERPRETED AS MOVING DIGITAL VISUALISATION Christin Bolewski Loughborough School of Art and Design Loughborough, UK, LE11 3TU [email protected] Abstract – This paper is based on a practice-led research project and includes the demonstration of video art. It investigates how East Asian traditions of landscape art can be understood through reference to the condition of Western contemporary visual culture. Proceeding from Chinese thought and aesthetics the traditional concept of landscape painting ‘Shan-Shui-Hua’ is recreated in modern digital visualisation practice to explore form and question linear perspective that aims to represent realistic space. PERSPECTIVE AND TEMPORALITY IN TRADITIONAL CHINESE LANDSCAPE PAINTING The intended purpose and motivation of science and technological progress in our Western civilisation is mainly directed by achieving perfection in measuring and rendering the objective and accountable ‘truth’ of our world. With regard to the history of the development of visualisation tools this has continuously led towards the invention of hardware and software whose success is measured by its potential to render a more perfect representational image. The creation of real or hyper-real space is one of the main objectives in film and 3D visualisation practice. Based on the Renaissance tradition, achieving the effect of realistic space by the employment of linear perspective is a major preoccupation of Western visual culture. In the construction of a virtual 3D space the Cartesian grid is used to reconstruct this geometrical perspective, whereas Eastern culture has a concept of using multiple vanishing points that within which the creation of a realistic space is not one of its aims. -

2013 Editor Lindsay Shen, Phd

Journal of the royal asiatic society china Vol. 75 no. 1, 2013 Editor Lindsay Shen, PhD. Copyright 2013 RAS China. The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society China is published by Earnshaw Books on behalf of the Royal Asiatic Society China. Contributions The editors of the Journal invite submission of original unpublished scholarly articles and book reviews on the religion and philosophy, art and architecture, archaeology, anthropology and environment, of China. Books sent for review will be donated to the Royal Asiatic Society China Library. Contributors receive a copy of the Journal. Subscriptions Members receive a copy of the journal, with their paid annual membership fee. Individual copies will be sold to non-members, as available. Library Policy Copies and back issues of the Journal are available in the library. The library is available to members. www.royalasiaticsociety.org.cn Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society China Vol. 75 No. 1, 2013 978-988-8422-44-9 © 2013 Royal Asiatic Society China The copyright of each article rests with the author. EB086 Designed and produced for RAS China by Earnshaw Books Ltd. (Hong Kong) Room 1801, 18F, Public Bank Centre, 120 Des Voeux Road Central, Hong Kong All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in material form, by any means, whether graphic, electronic, mechanical or other, including photocopying or information storage, in whole or in part. May not be used to prepare other publications without written permission from the publisher. The Royal Asiatic Society China thanks Earnshaw -

Teachers' Guide for Painting

Painting TO THE TEACHER OBJECTIVES OF THIS UNIT: To introduce students to one of the major Chinese arts. To raise questions about what we can infer from paintings about social and material life. To introduce the distinction between court and scholar painting and allow discussion of the emergence of landscape as a major art form. TEACHING STRATEGIES: This unit can be taught as a general introduction to Chinese painting or the two main subsections can be taught independently, depending on whether the teacher is more interested in using painting to teach about other things or wants to discuss painting itself as an art. WHEN TO TEACH: In a chronologically-organized course, Painting should not be used before the Song period, as most of the examples in this unit are from the Song and Yuan dynasties. If both Calligraphy and Painting are used, Calligraphy should precede Painting, as it provides valuable information on social and aesthetic values which informed the study, evaluation, and collecting of both types of works of art. This unit would also be appropriate in a course on Chinese art. http://depts.washington.edu/chinaciv/painting/tptgintr.htm (1 of 3) [11/26/2001 10:59:00 AM] Painting We know from textual and archaeological sources that painting was practiced in China from very early times and in a variety of media. Wall paintings were produced in great numbers in the early period of China's history, but because so little early architecture in China remained intact over the centuries, few of these large-scale paintings have survived. -

The Role of Landscape Art in Cultural and National Identity: Chinese and European Comparisons

sustainability Article The Role of Landscape Art in Cultural and National Identity: Chinese and European Comparisons Xiaojing Wen 1,* and Paul White 2 1 School of Design, Shanghai Jiaotong University, Shanghai 200240, China 2 Department of Geography, University of Sheffield, Sheffield S10 2TG, UK; P.White@sheffield.ac.uk * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 5 June 2020; Accepted: 3 July 2020; Published: 7 July 2020 Abstract: The depiction of landscape in art has played a major role in the creation of cultural identities in both China and Europe. Landscape depiction has a history of over 1000 years in China, whilst in Europe its evolution has been more recent. Landscape art (shan shui) has remained a constant feature of Chinese culture and has changed little in style and purpose since the Song dynasty. In Europe, landscape depictions have been significant in the modern determination of cultural and national identities and have served to educate consumers about their country. Consideration is given here to Holland, England, Norway, Finland and China, demonstrating how landscape depictions served to support a certain definition of Chinese culture but have played little political role there, whilst in Europe landscape art has been produced in a variety of contexts, including providing support for nationalism and the determination of national identity. Keywords: landscape art; Chinese landscapes; European landscapes; cultural identity; national identity 1. Introduction The concept of cultural identity commonly refers to a feeling of belonging to a group in which there are a number of shared attributes which might include, among other things, knowledge, beliefs, artefacts, arts, morals, and law. -

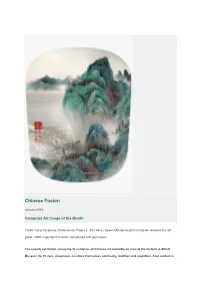

Chinese Fusion

Chinese Fusion January 2014 Computer Art Image of the Month Credit: Yang Yongliang, Viridescence, Pages 2, 44 x 44cm, Epson Ultragiclee print on Epson textured fine art paper, 2009. Copyright the artist, reproduced with permission. The superb exhibition surveying 12 centuries of Chinese art currently on view at the Victoria & Albert Museum (to 19 Jan), showcases a culture that values continuity, tradition and repetition. Also evident is the strong history within Chinese art of honouring the artistic achievements of the preceding generation through the deliberate mimicking of previous styles of painting. The Shanghai-based Yang Yongliang, our featured artist this month, does exactly this but gives a contemporary interpretation to his traditionally-inspired art, utilising new technology and updated imagery. A fusion of the old with new modalities from the West creates something entirely new in art. Yang Yongliang cleverly recreates the main principles of Chinese blue-green Shan shui (‘mountain and water’) paintings which first arose in the fifth century using mineral dyes for the vibrant hues. Shan shui works are painted and designed according to elemental theory with the five elements representing various parts of the natural world. Yang uses a camera and computer to manipulate his imagery of urban life thus subtly subverting traditional painting. In place of the historic natural landscapes filled with rock formations and craggy trees - perhaps even a contemplative scholar - in Yang’s work we see construction sites, large cranes, fly-overs and the assorted detritus of the rapidly growing, increasingly urbanised country that is contemporary China. The dreamlike Shan shui seamlessly morphs into shocking modernity. -

China/Avant-Garde: Exploring Modern China Through Art

CHINA/AVANT-GARDE: EXPLORING MODERN CHINA THROUGH ART CURRICULUM COMPONENT HISTORICAL ERAS IN CHINA 1949-1978 1978-1989 960-1279 1989-present Imperial China: Communist China Avant-Garde China Political Capitalist Song Dynasty China With the economic and political After the 1989 Tiananmen Classical era of Mao Zedong-led state reforms by Deng Xiaoping in Square protests, Chinese increased urbanization, take-over of private land 1978, China began to open citizens re-directed their agricultural production, and wealth with a series of itself to western influences and efforts toward greater commerce and trade, five-year plans that starved capitalist growth. Privatization individual wealth and industrial technology, millions of Chinese to of property and wealth ushered productivity. China’s and flourishing civil death, despite increased in the expectations of other economy, despite service system. agricultural production and industrialization. individual freedoms.. authoritarian political measures, would surge to become the largest in the world in the 21st century TERMS Communist Revolution Middle Kingdom Democracy Movement Mao Zedong Song Dynasty April 26 Editorial Five Year Plan Tiananmen Square Massacre Shan shui Great Leap Forward Taoism (Daoism) Political Capitalism Cultural Revolution Confucianism One Belt One Road Initiative Deng Xiaoping Qingming Scroll Special Economic Zones civil service system China-Avant-Garde Art Rainbow Bridge Exhibition CONTEXT: ART IN CHINA ERA IMPERIAL CHINA (Song COMMUNIST CHINA AVANT-GARDE CHINA POLITICAL CAPITALISM dynasty 960-1279) (1949-1978) (1978-1989) CHINA (1989-present) STYLE; Landscapes (shan shui or “Socialist in content, Challenges to Maoist ideology, Acceptance of China’s political THEMES; “mountain river”) style Chinese in style”; folk art, philosophical and cultural capitalist model of economic INFLUENCES painting or nianhua (traditional debates on humanism and freedoms held politically and • Spring festival art). -

Bracken Thesis.Indd

THINKING SHANGHAI A Foucauldian Interrogation of the Postsocialist Metropolis Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Technische Universiteit Delft, op gezag van de Rector Magnifi cus prof.dr.ir. J.T. Fokkema, voorzitter van het College voor Promoties, in het openbaar te verdedigen op donderdag 4 juni 2009 om 10.00 uur door Gregory BRACKEN Master of Science in Architecture, Delft University of Technology, The Netherlands Bachelor of Science in Architecture, Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland Diploma in Architecture, Bolton Street College of Technology, Dublin, Ireland geboren te Dublin, Ierland 1 Dit proefschrift is goedgekeurd door de promotor: Prof.dr. A. Graafl and Samenstelling promotiecommissie: Rector Magnifi cus, voorzitter Prof.dr. A. Graafl and, Technische Universiteit Delft, promotor Prof.dr.ir. T. de Jong, Technische Universiteit Delft Prof. M. Sparreboom, Universiteit Leiden Mw prof.dr. C. van Eyck, Universiteit Leiden Prof. B. de Meulder, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium Mw prof. M.C. Boyer, Princeton University, USA Dean prof. Heng C.K., National University of Singapore Prof.ir. U. Barbieri, Technische Universiteit Delft 2 SUMMARY This work is an investigation into Shanghai’s role in the twenty-fi rst century as it attempts to rejoin the global city network. It also examines the effects this move is having on the city, its people, and its public spaces. Shanghai’s intention to turn itself into the New York of Asia is not succeeding, in fact the city might be better trying to become the Chicago of Asia instead. As one of Saskia Sassen’s ‘global cit- ies’ Shanghai functions as part of a network that requires face-to-face contact, but it has also been able to benefi t from links that were forged during the colonial era (1842 to c.1949). -

Owning the Olympics

Owning the Olympics Owning the Olympics Narratives of the New China Monroe E. Price and Daniel Dayan, Editors THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS and THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN LIBRARY Ann Arbor Copyright © by Monroe E. Price and Daniel Dayan 2008 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2011 2010 2009 2008 4321 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN-13: 978-0-472-07032-9 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-472-07032-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-472-05032-1 (paper : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-472-05032-X (paper : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-472-02450-6 (electronic) Contents Introduction Monroe E. Price 1 I. De‹ning Beijing 2008: Whose World, What Dream? “One World, Different Dreams”: The Contest to De‹ne the Beijing Olympics Jacques deLisle 17 Olympic Values, Beijing’s Olympic Games, and the Universal Market Alan Tomlinson 67 On Seizing the Olympic Platform Monroe E. Price 86 II. Precedents and Perspectives The Public Diplomacy of the Modern Olympic Games and China’s Soft Power Strategy Nicholas J. Cull 117 “A Very Natural Choice”: The Construction of Beijing as an Olympic City during the Bid Period Heidi Østbø Haugen 145 Dreams and Nightmares: History and U.S.