2 Prophetic Times

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Treatise on Astral Projection V2

TREATISE ON ASTRAL PROJECTION V2 by Robert Bruce Copyright © 1999 Contents Part One................................................................................................................................. 1 Part Two................................................................................................................................. 6 Part Three .............................................................................................................................. 12 Part Four ............................................................................................................................... 17 Part Five ................................................................................................................................ 21 Part Six................................................................................................................................... 27 Part Seven .............................................................................................................................. 34 Part Eight............................................................................................................................... 41 Book Release – “Astral Dynamics”....................................................................................... 51 Book Release – “Practical Psychic Self-Defense”................................................................ 52 i Copyright © Robert Bruce 1999 1 Part One This version has been completely rewritten and updated, with thought to all -

Feast of Our Lady of Lourdes ‒ Marian High School, February 11

Feast of Our Lady of Lourdes – Marian High School, February 11, 2019 Most Reverend Bishop Kevin C. Rhoades “It was 161 years ago today, on February 11, 1858, that the Blessed Virgin Mary first appeared to the 14-year old Bernadette Soubirous at the grotto of Massabielle near the village of Lourdes in France. It was the first of 18 apparitions. At this first apparition, Bernadette first saw a light, then she saw a young lady who she said was “beautiful, more beautiful than any other.” She did not know it was the Virgin Mary. Bernadette said that the lady smiled at her and spoke to her with much tenderness and love. She described the woman to others as ‘the beautiful lady.’ She was beautiful in every way, not just physically. It is hardly surprising that Mary should be beautiful, given that – during the last apparition on March 25th, 1858, she revealed her name to Bernadette. She said: “I am the Immaculate Conception.” Is this not the greatest beauty of Mary of Nazareth, the Mother of Jesus? She was without sin from the first moment of her existence. She was preserved by God from every stain of original sin. We call her Mary most holy. Her holiness was perfect. That’s why she’s the greatest of all the saints, the Queen of All Saints. That’s the patron title I gave to Bishop Dwenger High School some years ago, when I gave to your high school Our Lady of Lourdes as patroness. The young Bernadette saw the beauty of Mary. -

A Church That Teaches: a Guide to Our Lady of the Most Holy Trinity

A Church that Teaches A Guide to Our Lady of the Most Holy Trinity Chapel at Thomas Aquinas College A Church that Teaches A Guide to Our Lady of the Most Holy Trinity Chapel at Thomas Aquinas College Second Edition © 2010 quinas A C s o a l m l e o g h e T C 1 al 7 if 19 ornia - 10,000 Ojai Road, Santa Paula, CA 93060 • 800-634-9797 www.thomasaquinas.edu Foreword “This college will explicitly define itself by the Christian Faith and the tradition of the Catholic Church.” — A Proposal for the Fulfillment of Catholic Liberal Education (1969) Founding document of Thomas Aquinas College Dear Friend, In setting out on their quest to restore Catholic liberal education in the United States, the founders of Thomas Aquinas College were de- termined that at this new institution faith would be more than simply an adornment on an otherwise secular education. The intellectual tra- dition and moral teachings of the Catholic Church would infuse the life of the College, illuminating all learning as well as the community within which learning takes place. Just as the Faith would lie at the heart of Thomas Aquinas College, so too would a beautiful chapel stand at the head of its campus. From the time the College relocated in 1978 to its site near Santa Paula, plans were in place to build a glorious house of worship worthy of the building’s sacred purpose. Those plans were long deferred, however, due to financial limitations and the urgent need to establish basic campus essentials such as dining facilities, residence halls, and classrooms. -

Occult Worksheet

OCCULT WORKSHEET Participating in any of these activities does not automatically mean that demonic inroads are opened into a person’s life, but these activities can open a person and make them vulnerable. Occult games or activities Magic -- black or white Attend a séance or spiritualist meeting Attend or participate in Wicca (white witch) Participated in astrology by: activities or church read or follow horoscopes Attend or participate in witchcraft or voodoo astrology chart made for self Learned how to cast a magic spell Party games involved with: Practice magic (use of true supernatural automatic writing powers) clairsentience (through touch) Place, sent or spoken a curse against clairvoyance / mind reading someone crystal ball gazing Participated in chain letter where there was a ESP (Extra Sensory Perception) curse against those who did not participate healing magnetism Used a charm of any kind for protection hypnotism Participated in or entered into a blood pact or levitation (lifting bodies) covenant magic eight ball Sought healing though: mental suggestion magic spells mental telepathy charms Ouija Board Christian Scientist reader palm reading spiritualist perceiving auras witch doctor precognition shaman psychometry Practiced water witching or dowsing self hypnosis Predict sex of unborn child with divining rod speaking in a trance Read or possess books about magic, magic table tipping / lifting spells, or witchcraft tarot cards Played Dungeons and Dragons using spells telekinesis / parakinesis (move objects with -

Rezension Über: Owen Davies, a Supernatural War. Magic

Zitierhinweis Miller, Ian: Rezension über: Owen Davies, A Supernatural War. Magic, Divination, and Faith during the First World War, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019, in: Reviews in History, 2019, May, DOI: 10.14296/RiH/2014/2318, heruntergeladen über recensio.net First published: https://reviews.history.ac.uk/review/2318 copyright Dieser Beitrag kann vom Nutzer zu eigenen nicht-kommerziellen Zwecken heruntergeladen und/oder ausgedruckt werden. Darüber hinaus gehende Nutzungen sind ohne weitere Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber nur im Rahmen der gesetzlichen Schrankenbestimmungen (§§ 44a-63a UrhG) zulässig. Historically, wars have always witnessed reports of ghostly sightings and visions. However, the First World War is of particular interest as such phenomena occurred in a more modern, secular environment, at a time when science and secularisation had emerged as predominant ways of thinking about the world. In addition, the number of lives being lost due to conflict was unprecedented. However, the work of groups such as the Society for Psychical Research aside, secular scientific thought did not easily accommodate the idea of a world beyond our own populated by the departed. Nor did it entertain amulets, charms, astrology or belief in luck. Science had now relegated these to superstition and folklore. Owen Davies’ A Supernatural War: Magic, Divination and Faith during the First World War provides a compelling overview of (what might be termed) a ‘hidden history’ of the First World War, one that reveals European societies still enthralled by the supernatural even in the context of modern, technologised conflict. A Supernatural War commences with a discussion of how sociologists, psychologists and anthropologists considered the battlefields of French and Belgium to be a unique laboratory for research. -

The Antichrist by Arthur W

The Antichrist by Arthur W. Pink Christian Classics Ethereal Library About The Antichrist by Arthur W. Pink Title: The Antichrist URL: http://www.ccel.org/ccel/pink/antichrist.html Author(s): Pink, Arthur W. Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Source: Logos Research Systems, Inc. Rights: Copyright Christian Classics Ethereal Library Contributor(s): Steve Liguori (Converter) CCEL Subjects: All; LC Call no: BT985 .P5 LC Subjects: Doctrinal theology Invisible world (saints, demons, etc.) The Antichrist Arthur W. Pink Table of Contents About This Book. p. ii Title Page. p. 1 Foreword. p. 2 Introduction. p. 3 The Papacy Not the Antichrist. p. 10 The Person of the Antichrist. p. 19 I. The Antichrist Will Be a Jew. p. 19 II. The Antichrist Will Be the Son of Satan. p. 21 III. The Antichrist Will Be Judas Reincarnated. p. 25 Names And Titles of the Antichrist. p. 28 1. The Antichrist. p. 29 2. The Man of Sin, the Son of Perdition. p. 30 3. The Lawless One. p. 30 4. The Beast. p. 31 5. The Bloody and Deceitful Man. p. 31 6. The Wicked One. p. 32 7. The Man of the Earth. p. 32 8. The Mighty Man. p. 33 9. The Enemy. p. 33 10. The Adversary. p. 33 11. The Head Over Many Countries. p. 34 12. The Violent Man. p. 34 13. The Assyrian. p. 34 14. The King of Babylon. p. 35 15. Son of the Morning. p. 35 16. The Spoiler. p. 36 17. The Nail. p. 36 18. The Branch of the Terrible Ones. -

Queenship of Mary -- Queen-Mother George F

Marian Library Studies Volume 28 Article 6 1-1-2007 Queenship of Mary -- Queen-Mother George F. Kirwin Follow this and additional works at: http://ecommons.udayton.edu/ml_studies Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Kirwin, George F. (2007) "Queenship of Mary -- Queen-Mother," Marian Library Studies: Vol. 28, Article 6, Pages 37-320. Available at: http://ecommons.udayton.edu/ml_studies/vol28/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Marian Library Publications at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marian Library Studies by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. George F. Kirwin, O.M.I. QUEENS HIP OF MARY - QUEEN -MOTHER TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD 5 L.J .C. ET M.l. 7 CHAPTER I HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT 11 Scripture 14 Tradition And Theology 33 L~~y ~ Art M Church Teaching 61 "Ad Caeli Reginam" 78 CHAPTER II THE NATURE OF MARY's QuEENSHIP 105 Two ScHOOLS OF THOUGHT 105 De Gruyter: Mary, A Queen with Royal Power 106 M.J. Nicolas: Mary, Queen Precisely as Woman 117 Variations on a Theme 133 CHAPTER III vATICAN II: A CHANGE OF PERSPECTIVE 141 Vatican II and Mariology 141 Mary, Daughter of Sion 149 Mary and the Church 162 CHAPTER IV MARY: QuEEN-MOTHER IN SALVATION HISTORY 181 Salvation History and the Kingdo 182 The Gebirah 205 The Nature of Mary's Queenship in Light of the Queen-Mother Tradition 218 Conclusion 248 Mary as the Archetype of the Church in the History of Salvation 248 BIBLIOGRAPHY 249 Books 249 Select Marian Resources 259 International Mariological-Marian Congresses 259 Proceedings of Mariological Societies 259 National Marian Congresses 260 Specialized Marian Research/Reference Publications 260 Articles 260 Papal Documents Referenced in this Study 283 QUEENSHIP OF MARY- QUEEN-MOTHER 39 28 (2007-2008) MARIAN LIBRARY STUDIES 37-284 FOREWORD This book is the result of the collaboration of many individuals and groups who provided me with the support and encouragement I needed to bring the project to a successful conclusion. -

What Do We Know About Angels?

What do we know about angels? For Catholics, angels are more than Christmas tree toppers. Belief in the supernatural appearances of heavenly figures is part of the fabric of our faith. But how much do we know about angels? Depictions of angels as winged creatures are ubiquitous in art, and belief in them is found across the Abrahamic religious traditions. The Christian conception of angels derives from the Jewish characterization as pure spirit, created beings that are messengers of God (from Greek angelos “messenger”) and were created before humanity was. Some have feast days, such as the three named archangels — Michael, Gabriel and Raphael — on Sept. 29; the feast of the guardian angels is celebrated Oct. 2. Churches, prayers and devotions are dedicated to these celestial beings. So what does the Church teach about angels? Where do angels appear in Scripture? Shutterstock Angels appear throughout the Bible in both dreams and bodily form: The Book of Revelation recounts a vision of seven angels with trumpets standing before God (cf. Rv 8:1-2). In the Old Testament, Jacob dreams of a ladder with angels ascending and descending (Gn 28:10-12). Angels are sent to exhibit God’s strength: An angel remained guarding the tree of life after Adam and Eve were cast out of the garden (Gn 3:20-24). King David and the Israelites were to be punished by God by an angel, but with repentance and sacrifice of the king, the angel relented in the plan to destroy Jerusalem (2 Sm 24). Angels are often sent for protection: In the Book of Exodus, Moses receives an angel sent by God to guard him and lead him into the Promised Land (3:2, 23:20-22). -

![The Compleat Works of Nostradamus -=][ Compiled and Entered in PDF Format by Arcanaeum: 2003 ][=](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3323/the-compleat-works-of-nostradamus-compiled-and-entered-in-pdf-format-by-arcanaeum-2003-2343323.webp)

The Compleat Works of Nostradamus -=][ Compiled and Entered in PDF Format by Arcanaeum: 2003 ][=

The Compleat Works of Nostradamus -=][ compiled and entered in PDF format by Arcanaeum: 2003 ][=- Table of Contents: Preface Century I Century II Century III Century IV Century V Century VI Century VII Century VIII Century IX Century X Epistle To King Henry II Pour les ans Courans en ce Siecle (roughly translated: for the years’ events in this century) Almanacs: 1555−1563 Note: Many of these are written in French with the English Translation directly beneath them. Preface by: M. Nostradamus to his Prophecies Greetings and happiness to César Nostradamus my son Your late arrival, César Nostredame, my son, has made me spend much time in constant nightly reflection so that I could communicate with you by letter and leave you this reminder, after my death, for the benefit of all men, of which the divine spirit has vouchsafed me to know by means of astronomy. And since it was the Almighty's will that you were not born here in this region [Provence] and I do not want to talk of years to come but of the months during which you will struggle to grasp and understand the work I shall be compelled to leave you after my death: assuming that it will not be possible for me to leave you such [clearer] writing as may be destroyed through the injustice of the age [1555]. The key to the hidden prediction which you will inherit will be locked inside my heart. Also bear in mind that the events here described have not yet come to pass, and that all is ruled and governed by the power of Almighty God, inspiring us not by bacchic frenzy nor by enchantments but by astronomical assurances: predictions have been made through the inspiration of divine will alone and the spirit of prophecy in particular. -

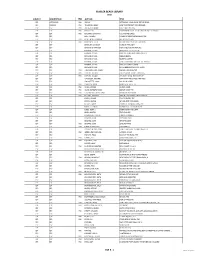

Flagler Beach Library Esp P. 1

FLAGLER BEACH LIBRARY 2015 SUBJECT DESCRIPTION TYPE AUTHOR TITLE ESP ASTROLOGY PBK ZODIAC ASTROLOGY: YOUR GUIDE TO THE STARS ESP DREAMS PBK THURSTON, MARK HOW TO INTERPRET YOUR DREAMS ESP ESP PBK ALTEA, ROSEMARY EAGLE AND THE ROSE ESP ESP PBK BADER, LOIS COMPANION GUIDE TO THE ONLY PLANET OF CHOICE ESP ESP PBK BALDWIN, CHRISTINA CALLING THE CIRCLE ESP ESP BALL, PAMELA POWER OF CREATIVE THINKING. THE ESP ESP PBK BOYER & NISSENBAUM SALEM POSSESSED ESP ESP PBK BRADY & ST. LIFER DISCOVERING YOUR SOUL MISSION ESP ESP BRINKLEY, DANNION SAVED BY THE LIGHT ESP ESP BROWNE & HARRISON PAST LIVES, FUTURE HEALING ESP ESP BROWNE, SYLVIA ADVENTURES OF A PSYCHIC ESP ESP BROWNE, SYLVIA GOD, CREATION AND TOOLS FOR LIFE ESP ESP BROWNE, SYLVIA PHENOMENON ESP ESP BROWNE, SYLVIA SECRET SOCIETIES ESP ESP BROWNE, SYLVIA SECRETS AND MYSTERIES OF THE WORLD ESP ESP BROWNE, SYLVIA SPIRITUAL CONNECTIONS ESP ESP BROWNE, SYLVIA SYLVIA BROWN'S BOOK OF ANGEL ESP ESP PBK CALLEMAN, CARL JOHAN MAYAN CALENDAR, THE ESP ESP PBK CAPUTO, THERESA THERE'S MORE TO LIFE THAN THIS ESP ESP PBK CAPUTO, THERESA YOU CAN'T MAKE THIS STUFF UP ESP ESP CAVENDISH, RICHARD MAN MYTH AND MAGIC PART TWO ESP ESP CHOQUETTE, SONIA ASK YOUR GUIDES ESP ESP PBK CIANCIOSI, JOHN MEDITATIVE PATH, THE ESP ESP PBK CLARK, JEROME UNEXPLAINED ESP ESP PBK CLOW, BARBARA HAND MAYAN CODE, THE ESP ESP PBK COOPER, MILTON WILLIAM BEHOLD A PALE HORSE ESP ESP PBK DELONG, DOUGLAS ANCIENT TEACHINGS FOR BEGINNERS ESP ESP DIXON, JEANNE CALL TO GLORY, THE ESP ESP DIXON, JEANNE MY LIFE AND PROPHECIES ESP ESP DOSSEY, LARRY POWER OF PREMONITIONS, THE ESP ESP DRUSE, ELEANOR JOURNALS OF ELEANOR DRUSE ESP ESP EADIE, BETTY J. -

Nostradamus the 21St Century and Beyond

Nostradamus The 21st Century and Beyond The present — which is still unfolding, is cloudy because we’re too close to that forest to see the trees as they emerge from the mists of time. But the thing all of us are most intrigued by is this: What does Nostradamus tell us about our own future —which, after all, is where we’ll be spending all our time? Is it to be all doom and gloom as some read into Nostradamus? Or were those frightening scenarios merely reflections of the prophet’s own gloomy character and the superstitious, medieval mind-set that produced him? Page 1 of 31 Nostradamus The 21st Century and Beyond Any discussion of Nostradamus’ predictions about our future has to deal to some extent with what appear to be doomsday forecasts and the coming of the third Antichrist. That is too much a part of the Nostradamus saga. But only a part. He also had a lot to say about the glorious, golden days that lie before us. However, the one prediction that preoccupies most Nostradamus scholars to the point of obsession — and chills some to the bone — is the one he recorded in CX Q72 which reads: ------------------------------------------------------------------------------ “In the year 1999, and seven months from the sky will come the great King of Terror. He will bring to life the great King of the Mongols. Before and after war reigns happily.” ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- Most experts have interpreted this famous quatrain as the prophet’s vision of an Antichrist. If Napoleon was the first and Hitler the second, the big questions obviously are: Who’s the third Antichrist? Is he/she/it among us today? Or still decades, even centuries, in the future? According to Christian legend, the Antichrist is a person or power that will come to corrupt the world but will then be conquered by Christ’s Second Coming. -

Revelation 12: Female Figures and Figures of Evil

Word & World Volume XV, Number 2 Spring 1995 Revelation 12: Female Figures and Figures of Evil JOY A. SCHROEDER University of Notre Dame Notre Dame, Indiana HE TWELFTH CHAPTER OF THE APOCALYPSE DESCRIBES A HEAVENLY WOMAN Tclothed with the sun and crowned with twelve stars. Together with the Bride of Christ and the Whore of Babylon, she is one of three symbolic women who ap- pear in the visions of John of Patmos. A fourth woman, apparently an influential teacher in the church in Thyatira, is regarded by John as a false prophet, a “Jeze- bel” (Rev 2:20). Each woman of the Apocalypse is unequivocally aligned either with God or with Satan. These female images are part of a system of symbols used by an author who speaks to his audience in code. The woman of Revelation 12 is the mother of a son who is snatched into heaven. She is persecuted by a dragon, flees into the wilderness, and there is nour- ished by God. This symbolic woman has been variously interpreted as the Virgin Mary, Israel, Eve, and the church. In actuality, her identity is multifaceted. This es- say will explore the many aspects of her identity, examining those which are de- rived from the Old Testament, as well as those which come from sources outside the Bible. In particular, I will explore the woman’s relationship to the dragon, since this will shed light on how we are to understand the woman. I. THE QUEEN OF HEAVEN At the opening of chapter 12, John of Patmos describes his vision of a heav- enly woman persecuted by a dragon: And a great sign appeared in heaven, a woman clothed with the sun, and the JOY SCHROEDER is a Lutheran pastor and a doctoral student at the University of Notre Dame.