Young Massive Star Clusters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black-Hole Binaries, Gravitational Waves, and Numerical Relativity

Black-hole binaries, gravitational waves, and numerical relativity Joan Centrella∗ and John G. Baker† Gravitational Astrophysics Laboratory, NASA/GSFC, 8800 Greenbelt Road, Greenbelt, Maryland 20771, USA Bernard J. Kelly‡ and James R. van Meter§ CRESST and Gravitational Astrophysics Laboratory, NASA/GSFC, 8800 Greenbelt Road, Greenbelt, Maryland 20771, USA and Department of Physics, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, 1000 Hilltop Circle, Baltimore, Maryland 21250, USA (Dated: November 30, 2010) Understanding the predictions of general relativity for the dynamical interactions of two black holes has been a long-standing unsolved problem in theoretical physics. Black-hole mergers are monu- mental astrophysical events, releasing tremendous amounts of energy in the form of gravitational radiation, and are key sources for both ground- and space-based gravitational-wave detectors. The black-hole merger dynamics and the resulting gravitational waveforms can only be calculated through numerical simulations of Einstein’s equations of general relativity. For many years, nu- merical relativists attempting to model these mergers encountered a host of problems, causing their codes to crash after just a fraction of a binary orbit could be simulated. Recently, however, a series of dramatic advances in numerical relativity has allowed stable, robust black-hole merger simulations. This remarkable progress in the rapidly maturing field of numerical relativity, and the new understanding of black-hole binary dynamics that is emerging is chronicled. Important applications of these fundamental physics results to astrophysics, to gravitational-wave astronomy, and in other areas are also discussed. Contents G. Numerical Approximation Methods 15 H. Extracting the Physics 15 I. Prelude 2 V. Black-Hole Merger Dynamics and Waveforms 16 II. -

Are Gamma-Ray Bursts Signals of Supermassive Black Hole Formation?

Are Gamma-Ray Bursts Signals of Supermassive Black Hole Formation? K. Abazajian, G. Fuller, X. Shi Department of Physics, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, California 92093-0350 Abstract. The formation of supermassive black holes through the gravitational 4 collapse of supermassive objects (M ∼> 5 × 10 M⊙) has been proposed as a source of cosmological γ-ray bursts. The major advantage of this model is that such collapses are far more energetic than stellar-remnant mergers. The major drawback of this idea is the severe baryon loading problem in one-dimensional models. We can show that the observed log N − log P (number vs. peak flux) distribution for gamma-ray bursts in the BATSE database is not inconsistent with an identification of supermassive object collapse as the origin of the gamma-ray bursts. This conclusion is valid for a range of plausible cosmological and γ-ray burst spectral parameters. 1. Introduction We investigate aspects of a recent model for the internal engine powering γ-ray bursts (GRBs). This model produces a GRB fireball through neutrino emission and annihilation during the collapse of a supermassive object into a black hole (Fuller & Shi, 1998). This supermassive object may either be a relativistic cluster of stars or a single supermassive star. The collapse of a supermassive object provides an exceedingly large amount of energy to power the burst, much higher than the amount of energy available in stellar remnant models. In addition, the rate of collapse of these objects–when associated with galaxy-type structures–is arXiv:astro-ph/9812287v1 15 Dec 1998 similar to the GRB rate. -

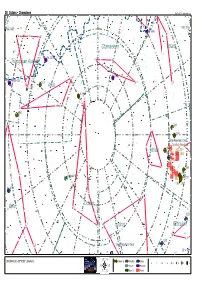

Skytools Chart

38 Octans - Chamaleon SkyTools 3 / Skyhound.com β NGC 6025 NGC 2516 IC 2448 β β ε γ Chamaeleon Volans δ ε ε PK 315-13.1 Triangulum Australe β γ 12h δ2 α ε 3195 ζ PK 325-12.1 1 α ζ 6101 5h η θ δ α Apus 09h 2 IC 4499 γ δ1 β γ ζ 6362 η 2 2210 η 2164 18h 06h Large Magellanic Cloud Tarantula Nebulaδ Mensa 2031 NGC 2014 NGC 1962 NGC 1955 ζ NGC 1874 NGC 1829 θ 1866 κ NGC 1770 1805 Collinder 411 NGC 1814 1978 1818 1783 03h 6744 21h β ε ε γ Octans Pavo ν -80° 00h ν 1559 β α δ θ Hydrus Reticulum β γ ι δ 1313 β Small Magellanic Cloud 0° 52° x 34° -7 ε ζ κ 00h00m00.0s -90°00'00" (Skymark) Globular Cl. Dark Neb. Galaxy 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Globule Planetary Open Cl. Nebula 38 Octans - Chamaleon GALASSIE Sigla Nome Cost. A.R. Dec. Mv. Dim. Tipo Distanza 200/4 80/11,5 20x60 NGC 292 Small Magellanic Cloud Tuc 00h 52m 38s +72° 48' 01” +2,80 318',0x204',0 SBm 0,2 Mly --- --- --- NGC 1313 Ret 03h 18m 15s -66° 29' 51” +9,70 9',5x7',2 Sbcd 13,5 Mly --- --- --- NGC 1559 Ret 04h 17m 36s -62° 47' 01" +11,00 4',2x2',1 SBc 34,0 Mly --- --- --- PGC 17223 Large Magellanic Cloud Dor 05h 23m 35s -69° 45' 22" +0,80 648',0x552',0 SBm 0,2 Mly --- --- --- NGC 6744 Pav 19h 09m 46s -63° 51' 28" +9,10 17',0x10',7 SABb 21,0 Mly --- --- --- AMMASSI APERTI Sigla Nome Cost. -

Gamma Ray Bursts from Stellar Collisions

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by CERN Document Server Gamma Ray Bursts from Stellar Collisions Brad M.S. Hansen & Chigurupati Murali Canadian Institute for Theoretical Astrophysics University of Toronto, Toronto, ON M5S 3H8, Canada Received ; accepted –2– ABSTRACT We propose that the cosmological gamma ray bursts arise from the collapse of neutron stars to black holes triggered by collisions or mergers with main sequence stars. This scenario represents a cosmological history qualitatively different from most previous theories because it contains a significant contribution from an old stellar population, namely the globular clusters. Furthermore, the gas poor central regions of globular clusters provide an ideal environment for the generation of the recently confirmed afterglows via the fireball scenario. Collisions resulting from neutron star birth kicks in close binaries may also contribute to the overall rate and should lead to associations between some gamma ray bursts and supernovae of type Ib/c. Subject headings: stars:neutron–supernovae:general–globular clusters:general– gamma rays:bursts– Galaxy:evolution –3– 1. Introduction The detection of X-ray, optical and radio afterglows from gamma-ray burst events (Costa et al 1997; van Paradijs et al 1997, Sahu et al 1997; Frail et al 1997) and concommitant redshifts (Metzger et al 1997) has provided strong support for the cosmological origin of the phenomenon. The success of the fireball model (Cavallo & Rees 1978; Rees & Meszaros 1992; Meszaros & Rees 1993) is largely independent of the origin of the energy, requiring only an energetic and baryon-poor event confined to small scales, thereby giving rise to a relativistic and optically thick outflow. -

On the Effects of Subvirial Initial Conditions and the Birth

Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 000, 000–000 (0000) Printed 24 October 2018 (MN LATEX style file v2.2) On the Effects of Subvirial Initial Conditions and the Birth Temperature of R136 Daniel P. Caputo1⋆, Nathan de Vries1 and Simon Portegies Zwart1 1Leiden Observatory, Leiden University, PO Box 9513, 2300 RA Leiden, the Netherlands 24 October 2018 ABSTRACT We investigate the effect of different initial virial temperatures, Q, on the dynamics of star clusters. We find that the virial temperature has a strong effect on many aspects of the resulting system, including among others: the fraction of bodies escaping from the system, the depth of the collapse of the system, and the strength of the mass segregation. These differences deem the practice of using “cold” initial conditions no longer a simple choice of convenience. The choice of initial virial temperature must be carefully considered as its impact on the remainder of the simulation can be profound. We discuss the pitfalls and aim to describe the general behavior of the collapse and the resultant system as a function of the virial temperature so that a well reasoned choice of initial virial temperature can be made. We make a correction to the previous theoretical estimate for the minimum radius, Rmin, of the cluster at the deepest (−1/3) moment of collapse to include a Q dependency, Rmin ≈ Q+N , where N is the number of particles. We use our numericalresults to infer more aboutthe initial conditions of the young cluster R136. Based on our analysis, we find that R136 was likely formed with a rather cool, but not cold, initial virial temperature (Q ≈ 0.13). -

The Role of Evolutionary Age and Metallicity in the Formation of Classical Be Circumstellar Disks 11

< * - - *" , , Source of Acquisition NASA Goddard Space Flight Center THE ROLE OF EVOLUTIONARY AGE AND METALLICITY IN THE FORMATION OF CLASSICAL BE CIRCUMSTELLAR DISKS 11. ASSESSING THE TRUE NATURE OF CANDIDATE DISK SYSTEMS J.P. WISNIEWSKI"~'~,K.S. BJORKMAN~'~,A.M. MAGALH~ES~",J.E. BJORKMAN~,M.R. MEADE~, & ANTONIOPEREYRA' Draft version November 27, 2006 ABSTRACT Photometric 2-color diagram (2-CD) surveys of young cluster populations have been used to identify populations of B-type stars exhibiting excess Ha emission. The prevalence of these excess emitters, assumed to be "Be stars". has led to the establishment of links between the onset of disk formation in classical Be stars and cluster age and/or metallicity. We have obtained imaging polarization observations of six SMC and six LMC clusters whose candidate Be populations had been previously identified via 2-CDs. The interstellar polarization (ISP). associated with these data has been identified to facilitate an examination of the circumstellar environments of these candidate Be stars via their intrinsic ~olarization signatures, hence determine the true nature of these objects. We determined that the ISP associated with the SMC cluster NGC 330 was characterized by a modified Serkowski law with a A,,, of -4500A, indicating the presence of smaller than average dust grains. The morphology of the ISP associated with the LMC cluster NGC 2100 suggests that its interstellar environment is characterized by a complex magnetic field. Our intrinsic polarization results confirm the suggestion of Wisniewski et al. that a substantial number of bona-fide classical Be stars are present in clusters of age 5-8 Myr. -

Gas and Dust in the Magellanic Clouds

Gas and dust in the Magellanic clouds A Thesis Submitted for the Award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Physics To Mangalore University by Ananta Charan Pradhan Under the Supervision of Prof. Jayant Murthy Indian Institute of Astrophysics Bangalore - 560 034 India April 2011 Declaration of Authorship I hereby declare that the matter contained in this thesis is the result of the inves- tigations carried out by me at Indian Institute of Astrophysics, Bangalore, under the supervision of Professor Jayant Murthy. This work has not been submitted for the award of any degree, diploma, associateship, fellowship, etc. of any university or institute. Signed: Date: ii Certificate This is to certify that the thesis entitled ‘Gas and Dust in the Magellanic clouds’ submitted to the Mangalore University by Mr. Ananta Charan Pradhan for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the faculty of Science, is based on the results of the investigations carried out by him under my supervi- sion and guidance, at Indian Institute of Astrophysics. This thesis has not been submitted for the award of any degree, diploma, associateship, fellowship, etc. of any university or institute. Signed: Date: iii Dedicated to my parents ========================================= Sri. Pandab Pradhan and Smt. Kanak Pradhan ========================================= Acknowledgements It has been a pleasure to work under Prof. Jayant Murthy. I am grateful to him for giving me full freedom in research and for his guidance and attention throughout my doctoral work inspite of his hectic schedules. I am indebted to him for his patience in countless reviews and for his contribution of time and energy as my guide in this project. -

Download the 2016 Spring Deep-Sky Challenge

Deep-sky Challenge 2016 Spring Southern Star Party Explore the Local Group Bonnievale, South Africa Hello! And thanks for taking up the challenge at this SSP! The theme for this Challenge is Galaxies of the Local Group. I’ve written up some notes about galaxies & galaxy clusters (pp 3 & 4 of this document). Johan Brink Peter Harvey Late-October is prime time for galaxy viewing, and you’ll be exploring the James Smith best the sky has to offer. All the objects are visible in binoculars, just make sure you’re properly dark adapted to get the best view. Galaxy viewing starts right after sunset, when the centre of our own Milky Way is visible low in the west. The edge of our spiral disk is draped along the horizon, from Carina in the south to Cygnus in the north. As the night progresses the action turns north- and east-ward as Orion rises, drawing the Milky Way up with it. Before daybreak, the Milky Way spans from Perseus and Auriga in the north to Crux in the South. Meanwhile, the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds are in pole position for observing. The SMC is perfectly placed at the start of the evening (it culminates at 21:00 on November 30), while the LMC rises throughout the course of the night. Many hundreds of deep-sky objects are on display in the two Clouds, so come prepared! Soon after nightfall, the rich galactic fields of Sculptor and Grus are in view. Gems like Caroline’s Galaxy (NGC 253), the Black-Bottomed Galaxy (NGC 247), the Sculptor Pinwheel (NGC 300), and the String of Pearls (NGC 55) are keen to be viewed. -

![Arxiv:1706.07545V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 23 Jun 2017 Russell and C-M Diagrams — Magellanic Clouds](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9647/arxiv-1706-07545v1-astro-ph-sr-23-jun-2017-russell-and-c-m-diagrams-magellanic-clouds-1189647.webp)

Arxiv:1706.07545V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 23 Jun 2017 Russell and C-M Diagrams — Magellanic Clouds

Draft version October 8, 2018 Preprint typeset using LATEX style AASTeX6 v. 1.0 DISCOVERY OF EXTENDED MAIN SEQUENCE TURN-OFFS IN FOUR YOUNG MASSIVE CLUSTERS IN THE MAGELLANIC CLOUDS Chengyuan Li Department of Physics and Astronomy, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW 2109, Australia Richard de Grijs Kavli Institute for Astronomy & Astrophysics and Department of Astronomy, Peking University, Yi He Yuan Lu 5, Hai Dian District, Beijing 100871, China and International Space Science Institute{Beijing, 1 Nanertiao, Zhongguancun, Hai Dian District, Beijing 100190, China Licai Deng Key Laboratory for Optical Astronomy, National Astronomical Observatories, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 20A Datun Road, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100012, China Antonino P. Milone Research School of Astronomy & Astrophysics, Australian National University, Mt Stromlo Observatory, Cotter Road, Weston, ACT 2611, Australia ABSTRACT An increasing number of young massive clusters (YMCs) in the Magellanic Clouds have been found to exhibit bimodal or extended main sequences (MSs) in their color{magnitude diagrams (CMDs). These features are usually interpreted in terms of a coeval stellar population with different stellar rotational rates, where the blue and red MS stars are populated by non- (or slowly) and rapidly rotating stellar populations, respectively. However, some studies have shown that an age spread of several million years is required to reproduce the observed wide turn-off regions in some YMCs. Here we present the ultraviolet{visual CMDs of four Large and Small Magellanic Cloud YMCs, NGC 330, NGC 1805, NGC 1818, and NGC 2164, based on high-precision Hubble Space Telescope photometry. We show that they all exhibit extended main-sequence turn-offs (MSTOs). -

![Arxiv:2006.10868V2 [Astro-Ph.SR] 9 Apr 2021 Spain and Institut D’Estudis Espacials De Catalunya (IEEC), C/Gran Capit`A2-4, E-08034 2 Serenelli, Weiss, Aerts Et Al](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3592/arxiv-2006-10868v2-astro-ph-sr-9-apr-2021-spain-and-institut-d-estudis-espacials-de-catalunya-ieec-c-gran-capit-a2-4-e-08034-2-serenelli-weiss-aerts-et-al-1213592.webp)

Arxiv:2006.10868V2 [Astro-Ph.SR] 9 Apr 2021 Spain and Institut D’Estudis Espacials De Catalunya (IEEC), C/Gran Capit`A2-4, E-08034 2 Serenelli, Weiss, Aerts Et Al

Noname manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) Weighing stars from birth to death: mass determination methods across the HRD Aldo Serenelli · Achim Weiss · Conny Aerts · George C. Angelou · David Baroch · Nate Bastian · Paul G. Beck · Maria Bergemann · Joachim M. Bestenlehner · Ian Czekala · Nancy Elias-Rosa · Ana Escorza · Vincent Van Eylen · Diane K. Feuillet · Davide Gandolfi · Mark Gieles · L´eoGirardi · Yveline Lebreton · Nicolas Lodieu · Marie Martig · Marcelo M. Miller Bertolami · Joey S.G. Mombarg · Juan Carlos Morales · Andr´esMoya · Benard Nsamba · KreˇsimirPavlovski · May G. Pedersen · Ignasi Ribas · Fabian R.N. Schneider · Victor Silva Aguirre · Keivan G. Stassun · Eline Tolstoy · Pier-Emmanuel Tremblay · Konstanze Zwintz Received: date / Accepted: date A. Serenelli Institute of Space Sciences (ICE, CSIC), Carrer de Can Magrans S/N, Bellaterra, E- 08193, Spain and Institut d'Estudis Espacials de Catalunya (IEEC), Carrer Gran Capita 2, Barcelona, E-08034, Spain E-mail: [email protected] A. Weiss Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics, Karl Schwarzschild Str. 1, Garching bei M¨unchen, D-85741, Germany C. Aerts Institute of Astronomy, Department of Physics & Astronomy, KU Leuven, Celestijnenlaan 200 D, 3001 Leuven, Belgium and Department of Astrophysics, IMAPP, Radboud University Nijmegen, Heyendaalseweg 135, 6525 AJ Nijmegen, the Netherlands G.C. Angelou Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics, Karl Schwarzschild Str. 1, Garching bei M¨unchen, D-85741, Germany D. Baroch J. C. Morales I. Ribas Institute of· Space Sciences· (ICE, CSIC), Carrer de Can Magrans S/N, Bellaterra, E-08193, arXiv:2006.10868v2 [astro-ph.SR] 9 Apr 2021 Spain and Institut d'Estudis Espacials de Catalunya (IEEC), C/Gran Capit`a2-4, E-08034 2 Serenelli, Weiss, Aerts et al. -

The Time of Perihelion Passage and the Longitude of Perihelion of Nemesis

The Time of Perihelion Passage and the Longitude of Perihelion of Nemesis Glen W. Deen 820 Baxter Drive, Plano, TX 75025 phone (972) 517-6980, e-mail [email protected] Natural Philosophy Alliance Conference Albuquerque, N.M., April 9, 2008 Abstract If Nemesis, a hypothetical solar companion star, periodically passes through the asteroid belt, it should have perturbed the orbits of the planets substantially, especially near times of perihelion passage. Yet almost no such perturbations have been detected. This can be explained if Nemesis is comprised of two stars with complementary orbits such that their perturbing accelerations tend to cancel at the Sun. If these orbits are also inclined by 90° to the ecliptic plane, the planet orbit perturbations could have been minimal even if acceleration cancellation was not perfect. This would be especially true for planets that were all on the opposite side of the Sun from Nemesis during the passage. With this in mind, a search was made for significant planet alignments. On July 5, 2079 Mercury, Earth, Mars+180°, and Jupiter will align with each other at a mean polar longitude of 102.161°±0.206°. Nemesis A, a brown dwarf star, is expected to approach from the south and arrive 180° away at a perihelion longitude of 282.161°±0.206° and at a perihelion distance of 3.971 AU, the 3/2 resonance with Jupiter at that time. On July 13, 2079 Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune+180° will align at a mean polar longitude of 299.155°±0.008°. Nemesis B, a white dwarf star, is expected to approach from the north and arrive at that same longitude and at a perihelion distance of 67.25 AU, outside the Kuiper Belt. -

7.5 X 11.5.Threelines.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-19267-5 - Observing and Cataloguing Nebulae and Star Clusters: From Herschel to Dreyer’s New General Catalogue Wolfgang Steinicke Index More information Name index The dates of birth and death, if available, for all 545 people (astronomers, telescope makers etc.) listed here are given. The data are mainly taken from the standard work Biographischer Index der Astronomie (Dick, Brüggenthies 2005). Some information has been added by the author (this especially concerns living twentieth-century astronomers). Members of the families of Dreyer, Lord Rosse and other astronomers (as mentioned in the text) are not listed. For obituaries see the references; compare also the compilations presented by Newcomb–Engelmann (Kempf 1911), Mädler (1873), Bode (1813) and Rudolf Wolf (1890). Markings: bold = portrait; underline = short biography. Abbe, Cleveland (1838–1916), 222–23, As-Sufi, Abd-al-Rahman (903–986), 164, 183, 229, 256, 271, 295, 338–42, 466 15–16, 167, 441–42, 446, 449–50, 455, 344, 346, 348, 360, 364, 367, 369, 393, Abell, George Ogden (1927–1983), 47, 475, 516 395, 395, 396–404, 406, 410, 415, 248 Austin, Edward P. (1843–1906), 6, 82, 423–24, 436, 441, 446, 448, 450, 455, Abbott, Francis Preserved (1799–1883), 335, 337, 446, 450 458–59, 461–63, 470, 477, 481, 483, 517–19 Auwers, Georg Friedrich Julius Arthur v. 505–11, 513–14, 517, 520, 526, 533, Abney, William (1843–1920), 360 (1838–1915), 7, 10, 12, 14–15, 26–27, 540–42, 548–61 Adams, John Couch (1819–1892), 122, 47, 50–51, 61, 65, 68–69, 88, 92–93,