A Thesis Entitled the Influence of Culture And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I"'-T.:.J,'I""6"

FLACSO - ECUADOR CHC COLEGIO ANDINO Facultad Latinoame~.~Sociales Centro de Estudios Regionales Andinos "'Bartolomé de las Casas" .Poder y Violencia en los Andes: a propósito de la costumbre del Takanakuy en la Comunidad Campesina de Ccoyo, Cusca.. Tesis para optar el Título de Magíster en Ciencias Sociales con especialidad en: Derecho y Sociedad Gustavo Adolfo Arias Díaz ~:i"'-t.:.j,'i""6"'¡-6"" ",.,~"'~ ,,<. ',-~"':' / r- Noviembre de 2003 INTRODUCCION. .. ,..... ,.. .. ... .., . ,. I Ubicacióny Condiciones geográficas de la Comunidad Campesina de Ccoyo . 1 El origen mítico de la costumbre del Takanakuy. , , r , , , • , •••• , 11 Orígenes eraohistóricos e históricos del Tasanakuyen la C,C, de Ccoyo . 22 Celebración de las fiestas de la Virgende SantaAna; idiosincrasia de un pueblo, 31 El Takanakuy a la luz del Derecho Peruano; Violencia en los Andes. , . , , , 45 El ritual Takanakuy: ¿Manifestación del derecho consuetudinario? . , , . r, ,, , , s 58 ... ..Poder y violencia socialdeltakan3kUy" ,-,--~'-.-,-:~.- . --, -:-~. ---:--. -:-:-: .,.;.;, ...86 Conclusiones 1 r I ,f J I 1 I 1 lIt 1 ; , I , 1 I I , , r , , I I I , r I I I 1 I r I I I J 96 Bibliografía; , . , . , ; . , , , . ; . .. 110 ANEXOS • •J • BIBLIOGRAFÍA • AMNI8TIA INTERNACIONAL 1986 México, los derechos en zonas rurales: intercambio de documentos con el Gobierno • mexicano sobre violaciones de los derechos humanos en Oaxaca y Chiapas, Madrid • -~~~~~cc~-~---~c-':España:PubIicaciohe~s~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ _c~ ~c_c_c~~- _- c. ~-~--=----== • • 1986 Brasil: Violencia autorizada en el medio rural, Madrid - España: Publicaciones, • ATLAS DEPARTAMENTAL DEL PERU • 2003 Cuzco - Apurimac, Primera Edición, Lima: Ediciones Peisa S.A.C. • ALBO, Xavíer •t 1999 "Principales características del derecho consuetudinario", Articulo Primero La paz , - Bolivia. P. 14-17 ~ BALLON, Francisco ~ 2002 "El sistema de administración de justicia de las rondas campesinas comunales - el caso de las rondas campesinas de las cuencas del Huancarmayo y el • Huarahuaramayo", AllpanchisPhuturinqa (Lima), Vol. -

“Proteccion Juridica Del Tinku Para Su Promocion Cultural, Ritual Y De Expresion Folklorica Boliviana”

UNIVERSIDAD MAYOR DE SAN ANDRES FACULTAD DE DERECHO Y CIENCIAS POLITICAS CARRERA DE DERECHO INSTITUTO DE INVESTIGACIONES Y SEMINARIOS TESIS DE GRADO “PROTECCION JURIDICA DEL TINKU PARA SU PROMOCION CULTURAL, RITUAL Y DE EXPRESION FOLKLORICA BOLIVIANA”. (Tesis para optar el grado de licenciatura en Derecho) Postulante: Mayckol Jesús Valencia Guzmán. Tutor: Dr. Javier Tapia Gutiérrez. La Paz – Bolivia 2013 i DEDICATORIA. A mis Sobrinos: Camila Renata Shanice, Iván Andrés, Sofía Gabriela y a todos los sobrinos que en un futuro no muy lejano formen parte de mi vida, por ser la descendencia de mi familia, por ser mis hijos putativos, por ser el impulso a mis proyectos de vida y la herramienta de amor, paz y cariño. A mi madre y padre por darme la vida y por ser mi apoyo incondicional en cada momento. ii AGRADECIMIENTO. A Dios por darme la vida y por hacer uno de mis sueños, hecho realidad. A mi Tutor Dr. Javier Tapia Gutiérrez por el apoyo y aporte de conocimientos a la presente tesis. A mis Padres por ser quienes guiaron mis pasos desde niño. A mi hermana Shirley Ivonne por ser mi apoyo incondicional y desmedido. A mis hermanos, por ser mis mejores amigos y compañeros de vida. Al Lic. Fernando Villazon Cossío, por ser quien cuido de mi economía, por darme la oportunidad de vida laboral y por ser quien apoyo mi tesis desde mi fuente de trabajo. A la Lic. Marcela Espinar Capriles porque encontré en ella una ayuda desmedida para poder llevar adelante la presente Tesis. A todos mis amigos, y particularmente a Frank Reynaldo Mollinedo Ramírez, porque desde su apoyo logístico permitieron llevar adelante mi proyecto. -

The Bioarchaeology of Societal Collapse and Regeneration in Ancient Peru Bioarchaeology and Social Theory

Bioarchaeology and Social Theory Series Editor: Debra L. Martin Danielle Shawn Kurin The Bioarchaeology of Societal Collapse and Regeneration in Ancient Peru Bioarchaeology and Social Theory Series editor Debra L. Martin Professor of Anthropology University of Nevada, Las Vegas Las Vegas , Nevada , USA More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/11976 Danielle Shawn Kurin The Bioarchaeology of Societal Collapse and Regeneration in Ancient Peru Danielle Shawn Kurin University of California Santa Barbara , USA Bioarchaeology and Social Theory ISBN 978-3-319-28402-6 ISBN 978-3-319-28404-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-28404-0 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016931337 © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifi c statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

Escuela De Postgrado

UNIVERSIDAD CATÓLICA DE SANTA MARÍA ESCUELA DE POSTGRADO DOCTORADO EN DERECHO LA JUSTICIA COMUNAL EN LA PROVINCIA DE CHUMBIVILCAS, DURANTE EL PERIODO 2010-2012 Tesis presentado por el Magíster: Efraín Trelles Sulla. Para optar el Grado Académico de: Doctor en Derecho. AREQUIPA – PERÚ 2014 A mi madre Olimpia Sulla viuda de Trelles por depositar en mí su fe y esperanza; a mi hermano Walter Trelles Sulla que Dios le tenga en su gloria; y a la memoria de miles de hombres y mujeres que han salido al encuentro de su identidad cultural y justicia. “Los pueblos a quienes no se hace justicia se la toman por sí mismos más tarde o más pronto”. Voltaire Í N D I C E LA JUSTICIA COMUNAL EN LA PROVINCIA DE CHUMBIVILCAS, DURANTE EL PERIODO 2010-2012 Pág. RESUMEN……………………………………………………………………………….. 9 SUMMARY………………………………………………………………………………. 11 INTRODUCCIÓN………………………………………………………………………... 13 CAPÍTULO I FUNDAMENTO TEÓRICO DE LA JUSTICIA COMUNAL Y EL SISTEMA DE JUSTICIA ESTATAL EN EL PERÚ 1.1. Generalidades…………………………………………………………….............. 18 1.2. Cultura e identidad cultural……………………………………………………….. 18 1.3. Perú: país pluricultural y multiétnico……………………………………………... 20 1.4. El reconocimiento constitucional del derecho a la identidad cultural.............. 22 1.5. El pluralismo jurídico………………………………………………………………. 25 1.6. La justicia comunal……………………………………………………….............. 27 1.6.1. Definición……………………………………………………………………. 27 1.6.2. Ordenamiento jurídico nacional e internacional que reconocen su existencia…………………………………………………………………….. 28 1.6.2.1. La Constitución Política del Perú de 1993……………................ 29 1.6.2.2. El Convenio 169 de la OIT (1989)……………………………….. 32 1.6.2.3. La Declaración de las Naciones Unidades sobre los Derechos de los Pueblos Indígenas……………………………. 34 1.6.2.4. -

FTM-WOTC-Handout-V5.Pdf

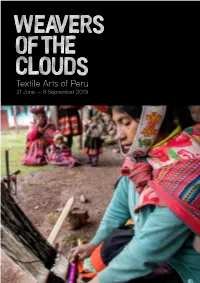

Credits Guest Curator: Hilary Simon With special thanks to: Head of Exhibitions: Alice Viera Albergaria Costa Borges Dennis Nothdruft Annie Hurlbut, Peruvian Connection Exhibition Design: Beth Ojari Armando Andrade Garment Mounting and Conservation: Camilo Garcia, IAG Cargo Gill Cochrane Carlos Agusto Dammert, Hellmann Exhibitions Coordinator: Marta Martin Soriano Worldwide Logistics Caryn Simonson, Chelsea College of Art Curator of ‘A Thread: Contemporary Art of Peru’: H.E Juan Carlos Gamarra Ambassador Claudia Trosso of Peru to Great Britain Jaime Cardenas, Director of Peru Trade Graphic Design: Hawaii and Investment Office Set Build and Installation: Setwo Ltd Leonardo Arana Yampe Graphic Production: Display Ways Mari Solari Handout Design: Madalena Studio Martin Morales Peruvian Embassy Head of Commercial and Operations: Promperú Melissa French Samuel Revilla and Luis Chaves, KUNA Operations Manager: Charlotte Neep Soledad Mujica Press and Marketing Officer: Philippa Kelly Susana de la Puente Front of House Coordinator: Vicky Stylianides Retail and Events Officer: Sadie Doherty Gallery Invigilation: Abu Musah PR Consultant: Penny Sychrava WEAVERS OF THE CLOUDS is a Fashion and Textile Museum exhibition Cover: ©Awamaki/Brianna Griesinger. Opposite: ©Mel Smith Opposite: Griesinger. ©Awamaki/Brianna Cover: Glossary of Peruvian Costume Women’s Traditional Dress Men’s Traditional Dress Ajotas – sandals made from recycled truck tyres. Ajotas – sandals made from recycled truck tyres. Camisa/blusa – a blouse. Buchis – short pants adapted from Spanish costume, which, Chumpi – a woven belt. depending on the area, come to the knee or a little longer. Juyuna – wool jackets that are worn under the women’s Centillo – finely decorated hat bands. shoulder cloths, with front panels decorated with white buttons. -

Universidad Nacional Del Altiplano

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DEL ALTIPLANO ESCUELA DE POSGRADO DOCTORADO EN DERECHO TESIS LAS TEORÍAS FILOSÓFICAS DEL DERECHO QUE SE APROXIMAN A LA JUSTICIA INDÍGENA U ORIGINARIO DEL PERÚ PRESENTADA POR: ALEXANDER HUAYTA VILCA PARA OPTAR EL GRADO ACADÉMICO DE: DOCTOR EN DERECHO PUNO, PERÚ 2021 DEDICATORIA El presente trabajo de investigación le dedico a mi querido padre por darme el soporte en los momentos más difíciles y por compartir mis momentos más alegres. A mi estimada e innegable madre, que desde el cielo me guía en el sendero académico y universitario. A los actores de los Pueblos Indígenas u Originarios por mantener la verdadera esencia del pluralismo jurídico que buscan promover e implementar como una teoría filosófica del Derecho; en muchos casos no es valorada por el Estado peruano. i AGRADECIMIENTO A la Universidad Nacional del Altiplano de Puno por ser mi primera casa de estudios y por compartir experiencias en mi formación académica. A mi asesor y a los miembros del jurado del presente trabajo de investigación por su gran apoyo incondicional y por sus sabias y acertadas orientaciones para la obtención de este lauro investigativo. ii ÍNDICE GENERAL Pág. DEDICATORIA i AGRADECIMIENTO ii ÍNDICE GENERAL iii ÍNDICE DE TABLAS v ÍNDICE DE FIGURAS vi RESUMEN vii ABSTRACT viii INTRODUCCIÓN 1 CAPÍTULO I REVISIÓN DE LITERATURA 1.1. Contexto y marco teórico 2 1.1.1. Conceptos de teoría, filosofía y derecho 2 1.1.2. Filosofía del derecho 5 1.1.3. Teoría general del derecho 6 1.1.4. Principales teorías filosóficas del derecho 7 1.1.4.1. -

Die Spur Des Heilgen. Raum, Ritual Und Die Feier Des

Die Spur des Heiligen , Axel Schäfer BERLIN STUDIES OF THE ANCIENT WORLD , gewaltsamer Missionierung, ist in den südlichen peruanischen An- den einer der populärsten Heiligen. Häufi g wird dies auf den Erfolg kolonialer Propaganda zurückgeführt. Demgegenüber unterstreicht die vorliegende Unter- suchung die aktive Rolle der indigenen Bevölkerung bei der Aneignung des Heiligen. Anhand von fünf Fallbeispielen wird die Feier des Santiago analysiert und gezeigt, welche Bedeutung der Kult im ländlichen Raum hat. Santiagos Patronat über die Pferde und seine wichtige Rolle bei der Segnung der Saatfrüchte belegen ebenso wie die engen Beziehungen zwischen kommunalen und familiären Santiagofeiern, zwischen katholischer Liturgie und indigenem Ritual, wie weit der Heilige in die bäuerliche Lebenswelt integriert ist. In der Auseinandersetzung mit dem Raum konstituie- ren die Feiernden die rituelle Landscha . Ihr imagina- tives und handlungsbezogenes Verhältnis zum Raum zeigt, wie Rituale und Symbole auf Orte und Richtun- gen bezogen werden und welche Reichweiten diese entfalten. Die Feiern fügen sich zu ganzen Festzyklen, in deren Rahmen Siedlungen und Landscha selemente rituell miteinander in Verbindung gesetzt werden. berlin studies of 36 the ancient world berlin studies of the ancient world · 36 edited by topoi excellence cluster Die Spur des Heiligen raum,ritual und die feier des santiago in den südlichen zentralen anden Axel Schäfer Bibliographische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek; detaillierte bibliographische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrubar. © 2016 Edition Topoi / Exzellenzcluster Topoi der Freien Universität Berlin und der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Abbildung Umschlag: Festtagsdecke mit Santiago und Motiven der Viehrituale (Ausschnitt).