Restoration of Blanket Bogs; Flood Risk Reduction and Other Ecosystem Benefits

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Blue” Carbon a Revised Guide to Supporting Coastal Wetland Programs and Projects Using Climate Finance and Other Financial Mechanisms

Coastal “blue” carbon A revised guide to supporting coastal wetland programs and projects using climate finance and other financial mechanisms Coastal “blue” carbon A revised guide to supporting coastal wetland programs and projects using climate finance and other financial mechanisms This revised report has been written by D. Herr and, in alphabetic order, T. Agardy, D. Benzaken, F. Hicks, J. Howard, E. Landis, A. Soles and T. Vegh, with prior contributions from E. Pidgeon, M. Silvius and E. Trines. The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN, Conservation International and Wetlands International concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN, Conservation International, Wetlands International, The Nature Conservancy, Forest Trends or the Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions. Copyright: © 2015 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, Conservation International, Wetlands International, The Nature Conservancy, Forest Trends and the Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions. Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Herr, D. T. Agardy, D. Benzaken, F. Hicks, J. Howard, E. Landis, A. Soles and T. Vegh (2015). Coastal “blue” carbon. -

Reconstructing Palaeoenvironments of the White Peak Region of Derbyshire, Northern England

THE UNIVERSITY OF HULL Reconstructing Palaeoenvironments of the White Peak Region of Derbyshire, Northern England being a Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Hull by Simon John Kitcher MPhysGeog May 2014 Declaration I hereby declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own, except where otherwise stated, and that it has not been previously submitted in application for any other degree at any other educational institution in the United Kingdom or overseas. ii Abstract Sub-fossil pollen from Holocene tufa pool sediments is used to investigate middle – late Holocene environmental conditions in the White Peak region of the Derbyshire Peak District in northern England. The overall aim is to use pollen analysis to resolve the relative influence of climate and anthropogenic landscape disturbance on the cessation of tufa production at Lathkill Dale and Monsal Dale in the White Peak region of the Peak District using past vegetation cover as a proxy. Modern White Peak pollen – vegetation relationships are examined to aid semi- quantitative interpretation of sub-fossil pollen assemblages. Moss-polsters and vegetation surveys incorporating novel methodologies are used to produce new Relative Pollen Productivity Estimates (RPPE) for 6 tree taxa, and new association indices for 16 herb taxa. RPPE’s of Alnus, Fraxinus and Pinus were similar to those produced at other European sites; Betula values displaying similarity with other UK sites only. RPPE’s for Fagus and Corylus were significantly lower than at other European sites. Pollen taphonomy in woodland floor mosses in Derbyshire and East Yorkshire is investigated. -

Newsletter Jan 2016

Derbyshire Archaeological Society Newsletter # 81 (Jan 2015) 1 DERBYSHIRE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER Issue 81 January 2016 2 Derbyshire Archaeological Society Newsletter # 81 (Jan 2016) DERBYSHIRE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY 2015 - 2016 PRESIDENT The Duke of Devonshire KCVO CBE VICE PRESIDENTS MR. J. R. MARJORAM, DR. P. STRANGE, MR. M.A.B. MALLENDER, MRS J. STEER, DR. D.V. FOWKES Chairman Mrs P. Tinkler, 53 Park Lane, Weston on Trent, of Council Derby, DE72 2BR Tel 01332 706716 Email; [email protected] Hon. Treasurer Mr P. Billson, 150 Blenheim Drive, Allestree, Derby, DE22 2GN Tel 01332 550725 e-mail; [email protected] Hon. Secretary Mrs B. A. Foster, 2, The Watermeadows, Swarkestone, Derbyshire, DE73 7FX Tel 01332 704148 e-mail; [email protected] Programme Sec. Mrs M. McGuire, 18 Fairfield Park, Haltwhistle, &Publicity Officer Northumberland. NE49 9HE Tel 01434 322906 e-mail; [email protected] Membership Mr K.A. Reedman, 107, Curzon St, Long Eaton, Secretary Derbyshire, NG10 4FH Tel 0115 9732150 e-mail; [email protected] Hon. Editors Dr. D.V. Fowkes, 11 Sidings Way, Westhouses, (Journal) Alfreton, Derby DE55 5AS Tel 01773 546626 e-mail; [email protected] Miss P. Beswick, 4, Chapel Row, Froggatt, Calver, Hope Valley, S32 3ZA Tel 01433 631256 e-mail; [email protected] Newsletter Editor Mrs B. A. Foster, 2, The Watermeadows, Swarkestone, Derbyshire, DE73 7FX Tel 01332 704148 e-mail; [email protected] Hon Assistant Mr. J.R. Marjoram, Southfield House, Portway, Librarian Coxbench, -

Appendix B. Recommendations for Reach 5 to 9

APPENDIX B RECOMMENDATIONS FOR REACHES 5-9 FROM TOWN OPEN SPACE PLAN September 27, 1995 B-1 MONTAUK REACHES 5-9 OPEN SPACE RECOMMENDATIONS Recommended SCTM # 0300- Acres Characteristics Disposition 7-1-2.2 NA parcel consists of 7-1-2.2 & 2.3 (37.6 acres), rezone to A3 Residence Montauk airport, duneland, freshwater wetlands, moorland & downs, State Significant Habitat, adjoins protected open space 7-1-2.3 NA see 7-1-2.2 see 7-1-2.2 7-2-9.22 1.8 underwater land at Reed Pond dreen, State public acquisition under- Significant Habitat water 7-2-9.4 2.6 underwater land adjacent to Town water public acquisition under- access, State Significant Habitat water 9-1-4 16.4 see 9-1-8.2 see 9-1-8.2 9-1-6 19.0 see 9-1-8.2 see 9-1-8.2 9-1-7 5.4 see 9-1-8.2 see 9-1-8.2 9-1-8.2 272 parcel consists of 9-1-4, 6, 7, & 8.2 (272 open space subdivision w/ partial public acres), Fort Pond Bay shorefront, historic acquisition and archaeological resources, Culloden Point, freshwater wetlands, protected species, trails and beach access, beech forest, moorland, State Significant Habitat, proposed Culloden Point subdivision B-2 MONTAUK REACHES 5-9 OPEN SPACE RECOMMENDATIONS Recommended SCTM # 0300- Acres Characteristics Disposition 12-2-2.19 97.7 large moorland block, woodland, freshwater rezone all of property to A3 Residence; open wetlands space subdivision (coordinate access and open space with tract to east)/possible golf course location (site-specific DEIS) 12-3-3 15.3 part of large moorland block, woodland, open space subdivision (coordinate access freshwater -

Geographic Classification, 2003. 577 Pp. Pdf Icon[PDF – 7.1

Instruction Manual Part 8 Vital Records, Geographic Classification, 2003 Vital Statistics Data Preparation U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Public Health Service Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics Hyattsville, Maryland October, 2002 VITAL RECORDS GEOGRAPHIC CLASSIFICATION, 2003 This manual contains geographic codes used by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) in processing information from birth, death, and fetal death records. Included are (1) incorporated places identified by the U.S. Bureau of the Census in the 2000 Census of Population and Housing; (2) census designated places, formerly called unincorporated places, identified by the U.S. Bureau of the Census; (3) certain towns and townships; and (4) military installations identified by the Department of Defense and the U.S. Bureau of the Census. The geographic place of occurrence of the vital event is coded to the state and county or county equivalent level; the geographic place of residence is coded to at least the county level. Incorporated places of residence of 10,000 or more population and certain towns or townships defined as urban under special rules also have separate identifying codes. Specific geographic areas are represented by five-digit codes. The first two digits (1-54) identify the state, District of Columbia, or U.S. Possession. The last three digits refer to the county (701-999) or specified urban place (001-699). Information in this manual is presented in two sections for each state. Section I is to be used for classifying occurrence and residence when the reporting of the geographic location is complete. -

Than Just a Bog: an Educational Resource for a and AS Level Geography and Higher Geography and Biology

www.sustainableuplands.org Originally prepared by: Jenny Townsend (Independent Educational Consultant) Professor Mark Reed (Birmingham City University) Funded by: Rural Economy & Land Use programme Cairngorms National Park Peak District National Park South West Water More than just a bog: an educational resource for A and AS Level Geography and Higher Geography and Biology . 2 Contents Activity Aims 3 Synopsis 3 Materials or props required 6 Arranging a site visit 6 About the authors 7 Support 7 Section 1: What are peatlands and why are they important? 8 Section 2: Damaged peatlands 21 Section 3: What does the future hold for peatlands? 25 Section 4: Involving everyone in decisions about our future environment – wind power case study 29 Section 5: Restoring peatlands 45 Section 6: Peatland National Parks 56 Section 7: Peat Cutting and Horticultural Use of Peat 61 Section 8: Case study – southwest moorlands 68 Section 9: Conclusions and further reading 83 3 Introduction to this resource: The resource is based on the latest research on peatlands, giving pupils a unique insight into the hidden beauty and value of these environments to UK society, how they have been damaged, and what we can do to restore and protect them. The resource is linked to SQA Higher and Advanced Higher curricula and the the OCR, CIE and AQA curricula for Geography A and AS level. It has been developed in collaboration with renowned learning and teaching consultant Jenny Townsend, University researchers, National Parks, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, Project Maya Community Interest Company and RSPB. The resource is funded by the Cairngorms National Park, Peak District National Park, South West Water and the Government’s Economic and Social Research Council via the Rural Economy & Land Use programme. -

Newsletter Summer-Fall 2003.Pub

Summer-Fall 2003 Newsletter of the Webster County Conservation Board From the Director’s Desk….. By Charlie Miller s of May 1, I have been working for the Webster County Conservation Board for 25 years. Re- A flecting back on those 25 years brings many memories as well as a lot of changes. When I first started in 1978, our shop was in a little 20’ X 30’ room with two small light bulbs, no telephone, no running water and no bathroom facilities. We barely had room to get any equipment in to work on it so most of the equipment repairs were made in the parking lot. The office was in the residence at Kennedy Park and Bob Heun, the Director at the time, would have to put in 90 to 100 hours per week because there were no office hours for the doorbell or telephone. There was also no air conditioning in the office or residence and I remember many times seeing Bob dripping sweat over the paper work he was trying to work on using the typewriter. In 1978 we had 4 full-time people on staff, the Di- rector, two park rangers including myself, and one full time maintenance person. The Direc- tor's wife, Lucy, helped clean the campground shower building and shelter and we had a seasonal maintenance person, two seasonal night patrol, and several lifeguards. In 1978 the Conservation Board owned and managed 7 county areas with a total of 550 acres scattered around the county. My, how things have changed. Our old shop is now a storage shed and the present shop is 50x50 with room to work on many projects at the same time. -

Environmental and Anthropogenic Controls Over Bacterial Communities in Wetland Soils

Environmental and anthropogenic controls over bacterial communities in wetland soils Wyatt H. Hartmana,1, Curtis J. Richardsona, Rytas Vilgalysb, and Gregory L. Brulandc aDuke University Wetland Center, Nicholas School of the Environment, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708; bBiology Department, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708; and cDepartment of Natural Resources and Environmental Management, University of Hawai’i at Manoa, Honolulu, HI 96822 Communicated by William L. Chameides, Duke University, Durham, NC, September 29, 2008 (received for review October 12, 2007) Soil bacteria regulate wetland biogeochemical processes, yet little specific phylogenetic groups of microbes affected by restoration is known about controls over their distribution and abundance. have not yet been determined in either of these systems. Eu- Bacteria in North Carolina swamps and bogs differ greatly from trophication and productivity gradients appear to be the primary Florida Everglades fens, where communities studied were unex- determinants of microbial community composition in freshwater pectedly similar along a nutrient enrichment gradient. Bacterial aquatic ecosystems (17, 18). To capture the range of likely composition and diversity corresponded strongly with soil pH, land controls over uncultured bacterial communities across freshwa- use, and restoration status, but less to nutrient concentrations, and ter wetland types, we chose sites representing a range of soil not with wetland type or soil carbon. Surprisingly, wetland resto- chemistry and land uses, including reference wetlands, agricul- ration decreased bacterial diversity, a response opposite to that in tural and restored wetlands, and sites along a nutrient enrich- terrestrial ecosystems. Community level patterns were underlain ment gradient. by responses of a few taxa, especially the Acidobacteria and The sites we selected represented a range of land uses Proteobacteria, suggesting promise for bacterial indicators of res- encompassing natural, disturbed, and restored conditions across toration and trophic status. -

Central and South America Report (1.8

United States NHEERL Environmental Protection Western Ecology Division May 1998 Agency Corvallis OR 97333 ` Research and Development EPA ECOLOGICAL CLASSIFICATION OF THE WESTERN HEMISPHERE ECOLOGICAL CLASSIFICATION OF THE WESTERN HEMISPHERE Glenn E. Griffith1, James M. Omernik2, and Sandra H. Azevedo3 May 29, 1998 1 U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service 200 SW 35th St., Corvallis, OR 97333 phone: 541-754-4465; email: [email protected] 2 Project Officer, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency 200 SW 35th St., Corvallis, OR 97333 phone: 541-754-4458; email: [email protected] 3 OAO Corporation 200 SW 35th St., Corvallis, OR 97333 phone: 541-754-4361; email: [email protected] A Report to Thomas R. Loveland, Project Manager EROS Data Center, U.S. Geological Survey, Sioux Falls, SD WESTERN ECOLOGY DIVISION NATIONAL HEALTH AND ENVIRONMENTAL EFFECTS RESEARCH LABORATORY OFFICE OF RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY CORVALLIS, OREGON 97333 1 ABSTRACT Many geographical classifications of the world’s continents can be found that depict their climate, landforms, soils, vegetation, and other ecological phenomena. Using some or many of these mapped phenomena, classifications of natural regions, biomes, biotic provinces, biogeographical regions, life zones, or ecological regions have been developed by various researchers. Some ecological frameworks do not appear to address “the whole ecosystem”, but instead are based on specific aspects of ecosystems or particular processes that affect ecosystems. Many regional ecological frameworks rely primarily on climatic and “natural” vegetative input elements, with little acknowledgement of other biotic, abiotic, or human geographic patterns that comprise and influence ecosystems. -

British Rainfall 1967

Met. 0. 853 METEOROLOGICAL OFFICE British Rainfall 1967 THE ONE HUNDRED AND SEVENTH ANNUAL VOLUME LONDON: HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE: 1973 U.D.C. 551.506.1 © Crown Copyright 1973 HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE Government Bookshops 49 High Holborn, London WC1V 6HB 13a Castle Street, Edinburgh EH2 3AR 109 St Mary Street, Cardiff CF1 1JW Brazennose Street, Manchester M60 8AS 50 Fairfax Street, Bristol BS1 3DE 258 Broad Street, Birmingham Bl 2HE 80 Chichester Street, Belfast BT1 4JY Government publications are also available through booksellers SBN 11 400250 9* Printed in England for Her Majesty's Stationery Office by Manor Farm Press, Alperton, Wembley, Middlesex Dd 507005 K7 5/73 Contents Page Introduction 1 Part I General table of rainfall Index to areal grouping of rainfall stations 5 General table of rainfall monthly and annual totals with amounts and dates of maximum daily falls 7 Part II Summary tables, maps and graphs with discussion 1 Main characteristics of the year 99 2 Monthly, annual and seasonal rainfall 101 3 Spells of rainfall deficiency and excess 123 4 Frequency distribution of daily amounts of rain 137 5 Heavy falls on rainfall days 152 6 Heavy falls in short periods 169 7 Evaporation and percolation 175 8 Potential evapotranspiration 180 Part III Special articles 1 Potential evapotranspiration data, 1967, by F. H. W. Green 184 2 Snow survey of Great Britain, season 1966-67, by R. E. Booth 191 3 Estimates and measurements of potential evaporation and evapotranspiration for operational hydrology, by B. G. Wales-Smith -

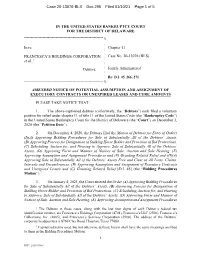

Amended Notice of Potential Assumption and Assignment of Executory Contracts Or Unexpired Leases and Cure Amounts

Case 20-13076-BLS Doc 295 Filed 01/10/21 Page 1 of 5 IN THE UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF DELAWARE ------------------------------------------------------------ x : In re: : Chapter 11 : FRANCESCA’S HOLDINGS CORPORATION, Case No. 20-13076 (BLS) 1 : et al., : : Debtors. Jointly Administered : : Re: D.I. 45, 266, 271 ------------------------------------------------------------ x AMENDED NOTICE OF POTENTIAL ASSUMPTION AND ASSIGNMENT OF EXECUTORY CONTRACTS OR UNEXPIRED LEASES AND CURE AMOUNTS PLEASE TAKE NOTICE THAT: 1. The above-captioned debtors (collectively, the “Debtors”) each filed a voluntary petition for relief under chapter 11 of title 11 of the United States Code (the “Bankruptcy Code”) in the United States Bankruptcy Court for the District of Delaware (the “Court”) on December 3, 2020 (the “Petition Date”). 2. On December 4, 2020, the Debtors filed the Motion of Debtors for Entry of Orders (I)(A) Approving Bidding Procedures for Sale of Substantially All of the Debtors’ Assets, (B) Approving Process for Designation of Stalking Horse Bidder and Provision of Bid Protections, (C) Scheduling Auction for, and Hearing to Approve, Sale of Substantially All of the Debtors’ Assets, (D) Approving Form and Manner of Notices of Sale, Auction and Sale Hearing, (E) Approving Assumption and Assignment Procedures and (F) Granting Related Relief and (II)(A) Approving Sale of Substantially All of the Debtors’ Assets Free and Clear of All Liens, Claims, Interests and Encumbrances, (B) Approving Assumption and Assignment of Executory -

Making Space for Water in the Upper Derwent Valley: Phase 2

Making Space for Water in the Upper Derwent Valley: Phase 2 Annual Report: 2012 - 2013 Report prepared for: by Moors for the Future Partnership March/April 2013 Moors for the Future Partnership The Moorland Centre, Edale, Hope Valley, Derbyshire, S33 7ZA, UK T: 01629 816 579 E: [email protected] W: www.moorsforthefuture.org.uk Suggested citation: Pilkington, M., Walker, J., Maskill, R., Allott, T. and Evans, M. (2012) Making Space for Water in the Upper Derwent Valley: Phase 2. Annual Report: 2012 – 2013. Moors for the Future Partnership, Edale. Executive Summary Project management and coordination activities (Milestone 1) The main restoration activities of heather brashing, liming, seeding, fertilising and dam construction were all completed in the spring of 2012, as the first phase of the Making space for Water (MS4W) project gave way to the second. This also marked the beginning of the post-restoration phase of monitoring for hydrological response. The only remaining restoration activities completed after this time were plug planting of moorland species (outside the monitoring areas), a planned “top-up” treatment of lime and fertilizer and some “top-up gully blocks, again outside the monitored area. New equipment has been bought, based on recommendations by University of Manchester; this is to be used as spares for replacing faulty items in the field and also for additional data gathering requirements to support the modelling exercise. There have been a number of meetings with the Environment Agency, the University of Manchester and the University of Durham in order to further clarify and formalise the contractual basis of the relationship in terms of the hydrological research and the related PhD, in addition to the more recent modelling exercise.