Rural Infrastructure Strategy in South Sudan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Sudan's Financial Sector

South Sudan’s Financial Sector Bank of South Sudan (BSS) Presentation Overview . Main messages & history/perspectives . Current state of the industry . Key issues – regulations, capitalization, skills, diversification, inclusion . The way forward “The road is under construction” Main Messages & History/perspectives . The history of financial institutions in South Sudan is a short one. Throughout Khartoum rule till the end of civil war in 2005, there were very few commercial banks concentrated in Juba, Wau and Malakal. South Sudanese were deliberately excluded from the economic system. As a result 90% of the population in South Sudan were not exposed to banking services . Access to finance was limited to Northern traders operating in Southern Sudan. In February 2008, Islamic banks left the South since the Bank of Southern Sudan(BOSS) introduced conventional banking . However, after the CPA the Bank of Southern Sudan, although a mere branch of the central bank of Sudan took a bold step by licensing local and expatriate banks that took interest to invest in South Sudan. South Sudan needs a stable, well diversified financial sector providing the right kinds of products and services with a level of intermediation and inclusion to support the country’s ambitions Current State of the Sector As of November 2013 . 28 Commercial Banks are now operating in South Sudan and more than 70 applications on the pipeline . 10 Micro Finance Institutions . 86 Forex Bureaus . A handful of Insurance companies Current state of the Sector (2) . Despite the increased number of financial institutions, competition is still limited and services are mainly concentrated in the urban hubs . -

The Greater Pibor Administrative Area

35 Real but Fragile: The Greater Pibor Administrative Area By Claudio Todisco Copyright Published in Switzerland by the Small Arms Survey © Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva 2015 First published in March 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission in writing of the Small Arms Survey, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organi- zation. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Publications Manager, Small Arms Survey, at the address below. Small Arms Survey Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies Maison de la Paix, Chemin Eugène-Rigot 2E, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Series editor: Emile LeBrun Copy-edited by Alex Potter ([email protected]) Proofread by Donald Strachan ([email protected]) Cartography by Jillian Luff (www.mapgrafix.com) Typeset in Optima and Palatino by Rick Jones ([email protected]) Printed by nbmedia in Geneva, Switzerland ISBN 978-2-940548-09-5 2 Small Arms Survey HSBA Working Paper 35 Contents List of abbreviations and acronyms .................................................................................................................................... 4 I. Introduction and key findings .............................................................................................................................................. -

River Nile Politics: the Role of South Sudan

UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI INSTITUTE OF DIPLOMACY AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES RIVER NILE POLITICS: THE ROLE OF SOUTH SUDAN R52/68513/2013 MATARA JAMES KAMAU A RESEARCH PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE AWARD OF A DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN INTERNATIONAL CONFLICT MANAGEMENT. OCTOBER 2015 DECLARATION This research project is my original work and has not been submitted for another Degree in any other University Signature ……………………………..…Date……………………………………. Matara James Kamau, R52/68513/2013 This research project has been submitted for examination with my permission as the University supervisor Signature………………………………...Date…………………………………… Prof. Maria Nzomo ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First and foremost, all thanks to God Almighty for the strength and ability to pursue this degree. For without him, there would be no me. I wish to express my sincere thanks to Professor Maria Nzomo the research supervisor for her tireless effort and professional guidance in making this project a success. I also extend my deepest gratitude to entire university academic staff in particular those working in the Institute of Diplomacy and International Studies. iii DEDICATION I dedicate this research project to my entire Matara‘s family for moral and financial support during the time of research iv ABSTRACT This study focused on River Nile Politics, a study of the role of South Sudan. The study relates to the emergence of a new state amongst existing riparian states and how this may resonate with trans-boundary conflicts. The independence of South Sudan has been revealed in this study to have a mixture of unanswered questions. The study is grounded on Collier- Hoeffer theory analysed the trans-boundary conflict based on the framework of many variable including: identities, economics, religion and social status in the Nile basin. -

END-OF-PROJECT EVALUATION BOMA-JONGLEI-EQUATORIA LANDSCAPE (BJEL) PROGRAM Performance Evaluation, 2008-2017

END-OF-PROJECT EVALUATION BOMA-JONGLEI-EQUATORIA LANDSCAPE (BJEL) PROGRAM Performance Evaluation, 2008-2017 OCTOBER 2017 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). It was prepared by the Evaluation Team, which comprised: Leo Bill Emerson (team leader), Alex B. Muhweezi (biodiversity expert) and James Thubo Ayul Ph.D. (livelihoods expert). END-OF-PROJECT EVALUATION BOMA-JONGLEI-EQUATORIA LANDSCAPE (BJEL) PROGRAM Performance Evaluation, 2008-2017 Contracted under 607300.01.060 Monitoring and Evaluation Support Project DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. (THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK) ABSTRACT This is an end-of-program performance evaluation report for the Boma-Jonglei-Equatoria Landscape (BJEL) program covering the 2008-2017 whose purpose is to assess the effectiveness, efficiency, sustainability and impact of the BJEL program. The results of the evaluation will inform future programming of similar project activities by USAID/South Sudan, the implementing partner Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), Government of the Republic of South Sudan (GRSS) entities and other donor organizations. The evaluation utilized a mixed-method approach, relying on quantitative and qualitative data from both primary and secondary sources, based on a set of indicators. The Evaluation interrogated information obtained and provided responses to the following five evaluation questions. a. How effective was the BJEL program in achieving project objectives? b. Did the project achieve the right focus and balance in terms of design, theory of change/development hypothesis, and strengthening strategies for sustainable safeguards of the wildlife population needs of South Sudan? c. -

Mining in South Sudan: Opportunities and Risks for Local Communities

» REPORT JANUARY 2016 MINING IN SOUTH SUDAN: OPPORTUNITIES AND RISKS FOR LOCAL COMMUNITIES BASELINE ASSESSMENT OF SMALL-SCALE AND ARTISANAL GOLD MINING IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EQUATORIA STATES, SOUTH SUDAN MINING IN SOUTH SUDAN FOREWORD We are delighted to present you the findings of an assessment conducted between February and May 2015 in two states of South Sudan. With this report, based on dozens of interviews, focus group discussions and community meetings, a multi-disciplinary team of civil society and government representatives from South Sudan are for the first time shedding light on the country’s artisanal and small-scale mining sector. The picture that emerges is a remarkable one: artisanal gold mining in South Sudan ‘employs’ more than 60,000 people and might indirectly benefit almost half a million people. The vast majority of those involved in artisanal mining are poor rural families for whom alluvial gold mining provides critical income to supplement their subsistence livelihood of farming and cattle rearing. Ostensibly to boost income for the cash-strapped government, artisanal mining was formalized under the Mining Act and subsequent Mineral Regulations. However, owing to inadequate information-sharing and a lack of government mining sector staff at local level, artisanal miners and local communities are not aware of these rules. In reality there is almost no official monitoring of artisanal or even small-scale mining activities. Despite the significant positive impact on rural families’ income, the current form of artisanal mining does have negative impacts on health, the environment and social practices. With most artisanal, small-scale and exploration mining taking place in rural areas with abundant small arms and limited presence of government security forces, disputes over land access and ownership exacerbate existing conflicts. -

Peace Is the Name of Our Cattle-Camp By

SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES pROjECT PEACE IS THE NAME OF OUR CATTLE-CAMP LOCAL RESPONSES TO CONFLICT IN EASTERN LAKES STATE, SOUTH SUDAN SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES PROJECT Peace is the Name of Our Cattle-Camp Local responses to conflict in Eastern Lakes State, South Sudan JOHN RYLE AND MACHOT AMUOM Authors John Ryle (co-author), Legrand Ramsey Professor of Anthropology at Bard College, New York, was born and educated in the United Kingdom. He is lead researcher on the RVI South Sudan Customary Authorities Project. Machot Amuom Malou (co-author) grew up in Yirol during Sudan’s second civil war. He is a graduate of St. Lawrence University, Uganda, and a member of The Greater Yirol Youth Union that organised the 2010 Yirol Peace Conference. Abraham Mou Magok (research consultant) is a graduate of the Nile Institute of Management Studies in Uganda. Born in Aluakluak, he has worked in local government and the NGO sector in Greater Yirol. Aya piŋ ëë kͻcc ἅ luël toc ku wεl Ɣͻk Ɣͻk kuek jieŋ ku Atuot akec kaŋ thör wal yic Yeŋu ye köc röt nͻk wεt toc ku wal Mith thii nhiar tͻͻŋ ku ran wut pεεc Yin aci pεεc tik riεl Acin ke cam riεlic Kͻcdit nyiar tͻͻŋ Ku cͻk ran nͻk aci yͻk thin Acin ke cam riεlic Wut jiëŋ ci riͻc Wut Atuot ci riͻc Yok Ɣen Apaak ci riͻc Yen ya wutdie Acin kee cam riεlic ëëë I hear people are fighting over grazing land. Cattle don’t fight—neither Jieŋ cattle nor Atuot cattle. Why do we fight in the name of grass? Young men who raid cattle-camps— You won’t get a wife that way. -

South Sudan 2021 Humanitarian Response Plan

HUMANITARIAN HUMANITARIAN PROGRAMME CYCLE 2021 RESPONSE PLAN ISSUED MARCH 2021 SOUTH SUDAN 01 About This document is consolidated by OCHA on behalf of the Humanitarian Country Team and partners. The Humanitarian Response Plan is a presentation of the coordinated, strategic response devised by humanitarian agencies in order to meet the acute needs of people affected by the crisis. It is based on, and responds to, evidence of needs described in the Humanitarian Needs Overview. Manyo Renk Renk SUDAN Kaka Melut Melut Maban Fashoda Riangnhom Bunj Oriny UPPER NILE Abyei region Pariang Panyikang Malakal Abiemnhom Tonga Malakal Baliet Aweil East Abiemnom Rubkona Aweil North Guit Baliet Dajo Gok-Machar War-Awar Twic Mayom Atar 2 Longochuk Bentiu Guit Mayom Old Fangak Aweil West Turalei Canal/Pigi Gogrial East Fangak Aweil Gogrial Luakpiny/Nasir Maiwut Aweil West UNITY Yomding Raja NORTHERN South Gogrial Koch Nyirol Nasir Maiwut Raja BAHR EL Bar Mayen Koch Ulang Kuajok WARRAP Leer Lunyaker Ayod GHAAL Tonj North Mayendit Ayod Aweil Centre Waat Mayendit Leer Uror Warrap Romic ETHIOPIA Yuai Tonj East WESTERN BAHR Nyal Duk Fadiat Akobo Wau Maper JONGLEI CENTRAL EL GHAAL Panyijiar Duk Akobo Kuajiena Rumbek North AFRICAN Wau Tonj Pochalla Jur River Cueibet REPUBLIC Tonj Rumbek Kongor Pochala South Cueibet Centre Yirol East Twic East Rumbek Adior Pibor Rumbek East Nagero Wullu Akot Yirol Bor South Tambura Yirol West Nagero LAKES Awerial Pibor Bor Boma Wulu Mvolo Awerial Mvolo Tambura Terekeka Kapoeta International boundary WESTERN Terekeka North Mundri -

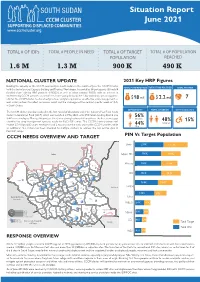

June 2021 Situation Report

SOUTH SUDAN Situation Report June 2021 TOTAL # OF IDPs TOTAL # PEOPLE IN NEED TOTAL # OF TARGET TOTAL # OF POPULATION POPULATION REACHED 1.6 M 1.3 M 900 K 490 K NATIONAL CLUSTER UPDATE 2021 Key HRP Figures Building the capacity of the CCCM community in South Sudan, in the month of June the CCCM Cluster TOTAL FUND REQUIRED TOTAL FUND RECEIVED TOTAL PARTNER held the rst of several Capacity Building and Training Workshops. Attended by 38 participants (30 male/8 females) from existing HRP partners (I/NGOs) as well as other national NGOs with an interest in implementing CCCM activities as part of the cluster going forward, the 2 day workshop was an opportu- nity for the CCCM cluster to share best practices and global guidelines on eective camp management, as 18 mil 2.2 mil 7 well as for partners to reect on lessons learnt and the challenges of the context specic needs of IDPs in South Sudan. DEMOGRAPHY TOTAL CHILDREN WITH DISABILITIES The CCCM cluster was also involved in the rst round of allocations under the Country Pool Fund South Sudan Humanitarian Fund (SSHF) which was launched in May 2021, with $50 million funding divided into 56% 3 dierent envelopes. During this process, the cluster strongly advocated to address the key service gaps Women identied by camp management agencies inside the PoC/ IDP camps. The CCCM cluster partners will 48% 15% Children receive 2.5 million USD under envelope 1 and 2, to carry out the static and mobile CCCM activities, while 44% Men an additional 16.5 million has been allocated to multiple clusters to address the key service gaps in PoC/IDP camps. -

International Development Select Committee to Press HMG to Take the Following Action

Written evidence submitted by WAGING PEACE 1. Summary 2. The UK’s role 3. The border 4. The presence of millions of non-Arab, non-Muslim Sudanese in Sudan 5. Abyei 6. South Kordofan 7. Blue Nile State 8. The need for explicit and enforceable rights for religious and ethnic minorities in Sudan 9. The need for enforceable rights for religious and ethnic minorities to form and belong to political and civil groups in Sudan 10. Fees charge by Sudan to tranship Southern oil to Port Sudan 11. Will ROSS become involved in conflicts north of the border? 12. Historical precedents for intervention by ROSS 13. Points of leverage 14. The need for urgent action 1. Summary This submission contends that the fledgling Republic of South Sudan’s (RoSS) economic, social and political success is dependent on resolving outstanding tensions with its northern neighbour, the government of Sudan, and specifically, the ruling National Congress Party (NCP). South Sudan’s security will be perpetually undermined unless the outstanding issues of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) and political differences with Khartoum are tackled, preferably in an international or regional forum. There is an important role for the UK in facilitating and advising such a forum, ensuring all parties fulfil their promises. The success of the CPA thus far has been immense, however, with so many destabilising issues left unresolved it is far from comprehensive. Continuing large scale human rights abuses in the border areas of Abyei, South Kordofan and Blue Nile states will sooner or later draw RoSS into open or proxy conflict with Khartoum. -

People Voice November Edition Edited.Cdr

To support November 2011 THE PEOPLE’S VOICE the peoples EDITORIAL TEAM INVITES Road accidents in South Sudan: Muslim community calls for religious tolerance COMMENTS, OPINIONS AND LETTERS. voice call, Who is to Blame? BY AGELE BENSON AMOS THE EDITORIAL TEAM RESERVES THE RIGHT TO PUBLICATION. +211957100855 By Yuggu Charles ordered me to surrender my car log book,” said Lupai. He added: “When I refused, they The Muslim community in Yei River by upholding harmony between the two County has called for religious harmony religions. The Arch-Deacon for Yei Over the past few years, there has been a threatened to remove my number plate. marked increase in the number of road They later forced me to pay the 30 and tolerance amongst various religious Episcopal Church Rev. Cosmas Gwagwe November 2011 Issue 9, Volume 0 001 Produced by UJOSS Free Copy accidents in South Sudan with many people Sudanese pounds but never gave me any groups in the young nation of South Samuel blamed the suspicion between losing their lives and others suffering receipt, an indication that this money Sudan in order to ensure a peaceful and Christians and Muslims on idle talkers terrible injuries. As the carnage continues would end up in their pockets. Such frustration makes drivers cause accidents”. prosperous future for all. The chairman who criticize other religions. Religious across the new country, The People's Voice of Muslims in the County, Kasim Yusuf, conflicts, he said, can always be resolved sought the views of citizens about the Although Lupai's logic may seem a bit far- Civilians continue to suffer at hands of rebels in Jonglei situation and who or what they think is to fetched, there is certainly some truth to the said it was only by respecting other through dialogue. -

South Sudan - EVD Risk Categorization and Location of Alerts, Nov 2018 South Sudan

South Sudan - EVD Risk Categorization and Location of Alerts, Nov 2018 South Sudan BOR AWERIAL 1 Rumbek SOUTH Lakes Jonglei PIBOR Data as of: 25 March 2018 WULU Map date: 26 November 2018 MVOLO TAMBURA Akpa ! TEREKEKA Centr al African !Rii Yubu Marangu MUNDRI LAPON KAPOETA Republic !Nyasi EAST NORTH MUNDRI WEST IBBA EZO KAPOETA Nabiapai 1 EAST ! Western Maridi MARIDI Anderi Equatoria Juba ! International !Airport Kapoeta YAMBIO Maridi airport Juba Embe Eastern !! 2 JUBA Equatoria Landilli Central NZARA Yambio ! KAPOETA SOUTH Rasol Equatoria Yambio ! airport ! 2 Nyaka Angebi ! ! Garamba Nabanga Park Gangura ! ! Skure ! ! 1 BUDI TORIT LAINYA YEI Lantoto Balago Yei Kenya ! ! Yei Airstrip2 SS!RRC ! Yei IKOTOS Libogo ! Senema ! KAJO-KEJI MAGWI Owinykibul Lobone Bira Busia ! Checkpoint ! Undago ! ! Birigo ! ! MOROBO Isebi Nimule ! ! Okaba Moyo 8 Nimule Kaya !! ! checkpoint Koboko Nimule 2 River Bas-Uele port Haut-Uele 3 Adjumani 7 1 Democra tic Arua Republic of the Congo Zombo 3 Pakawach Legend Uganda Active EVD sites Ituri EVD outbreak area 8 Ituri EVD high risk area Location of EVD alert Hoima 5 Internatilnal boundary Tshopo 1 Kasenyi 8 0 50 100 km The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply the expression The map reflects the currently available data and is subject to change according to further updates to the data. of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status Data source: South Sudan Ministry of Health, World Health Organization (WHO), OpenStreetMap MAP DATE: 26 November 2018 of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its Map production: WHO Health Emergencies Programme frontiers or boundaries. -

Covid-19 Weekly Situation Report

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN MINISTRY OF HEALTH PUBLIC HEALTH EMERGENCY OPERATIONS CENTRE (PHEOC) COVID-19 WEEKLY SITUATION REPORT Issue No: 15 Reporting Period: June 8-14, 2020 (week 24) 8,743 58 CUMULATIVE SAMPLES TESTED CUMULATIVE RECOVERIES 1,755 CUMULATIVE CONFIRMED CASES 30 3,599 CUMULATIVE DEATHS CUMULATIVE CONTACTS LISTED FOR FOLLOW UP 1. KEY HIGHLIGHTS A cumulative total of 1,755 confirmed cases have been registered including 32 imported cases as of 14 June 2020. 7 cases are currently isolated in health facilities in the Country: 1 is in moderate condition and 1 in severe condition. Currently the Juba Infectious Disease Unit (IDU) has 90% occupancy available. 58 recoveries (9 new) and 30 deaths have been recorded to date with case fatality rate (CFR) of 1.7%. 55 health care workers have been infected since the beginning of the outbreak. 3,599 cumulative contacts have been registered of which 2,214 have completed the 14-day quarantine and 1,385 are being followed. A total of 8,743 laboratory tests have been performed to date. There is cumulative total of 534 alerts of which 87% (n=344) have been verified and sampled; Most alerts have come from Central Equatoria 85% (n=454) and Eastern Equatoria States 4% (n=21) There are 17 (21%) COVID-19 affected counties among the 80 counties of South Sudan. 2. BACKGROUND South Sudan confirmed its first COVID-19 case on 5 April 2020 , to date 1,755 cases have been confirmed by the National Public Health Laboratory with 58 recoveries and 30 deaths, yielding case fatality rate (CFR) of 1.7%.