The Board for the Protection of Aborigines (1875–1883)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ON TAUNGURUNG LAND SHARING HISTORY and CULTURE Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc

ON TAUNGURUNG LAND SHARING HISTORY AND CULTURE Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc. is a part of the Australian Centre for Indigenous History, Research School of Social Sciences, The Australian National University, and gratefully acknowledges the support of the School of History and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, The Australian National University. Aboriginal History Inc. is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material. Views and opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily shared by Board members. Contacting Aboriginal History All correspondence should be addressed to the Editors, Aboriginal History Inc., ACIH, School of History, RSSS, 9 Fellows Road (Coombs Building), The Australian National University, Acton, ACT, 2601, or [email protected]. WARNING: Readers are notified that this publication may contain names or images of deceased persons. ON TAUNGURUNG LAND SHARING HISTORY AND CULTURE UNCLE ROY PATTERSON AND JENNIFER JONES Published by ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760464066 ISBN (online): 9781760464073 WorldCat (print): 1224453432 WorldCat (online): 1224452874 DOI: 10.22459/OTL.2020 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover photograph: Patterson family photograph, circa 1904 This edition © 2020 ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. Contents Acknowledgements ....................................... vii Note on terminology ......................................ix Preface .................................................xi Introduction: Meeting and working with Uncle Roy ..............1 Part 1: Sharing Taungurung history 1. -

AUG 2008 Wurundjeri RAP Appointment Decision Pdf 43.32 KB

DECISION OF THE VICTORIAN ABORIGINAL HERITAGE COUNCIL IN RELATION TO AN APPLICATION BY WURUNDJERI TRIBE LAND AND COMPENSATION CULTURAL HERITAGE COUNCIL INC TO BE A REGISTERED ABORIGINAL PARTY DATE OF DECISION: 22 AUGUST 2008 Decision The Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council (“the Council”) registers the Wurundjeri Tribe Land and Compensation Cultural Heritage Council Inc (“Wurundjeri Inc”) as a registered Aboriginal party (“RAP”) over part of its application area. A map showing the area for which Wurundjeri Inc has been made a RAP (“the RAP Area”) is attached (Attachment 1). The Council is still considering the remaining area for which Wurundjeri Inc has sought to be a RAP. Reasons for Decision The Council accepts that Wurundjeri Inc is an organisation that represents the Traditional Owners of the RAP Area. The members of Wurundjeri Inc are all descendants of a Woiwurrung / Wurundjeri man Bebejan, through his daughter Annie Borate (Boorat), and in turn, her son Robert Wandin (Wandoon). Bebejan was Ngurungaeta (headman) of the Wurundjeri people and was present at John Batman’s ‘treaty’ signing in 1835. Wurundjeri Inc was incorporated in 1985 and has had a long history of managing and protecting cultural heritage in its application area on behalf of Woiwurrung people. The Council was satisfied Wurundjeri Inc is capable of carrying out the functions of a RAP. RAP applications have also been made by other Traditional Owner groups in the vicinity of (and in some cases overlapping with) the Wurundjeri RAP application area. These include the Wathaurung/ Wathaurong people to the west, the Dja Dja Wurrung/ Jaara Jaara people to the north-west, the Taungurung people to the north, the Gunai/Kurnai people to the east and the Boon Wurrung/ Bunurong people to the south. -

Fighting Extinction Challenge Teacher Answers Middle Years 9-10

Fighting Extinction Challenge Teacher Answers Middle Years 9-10 Wurundjeri Investigation We are all custodians of the land, just as the Wurundjeri have been for thousands of years. During your independent investigation around the Sanctuary look for ways that the Wurundjeri people lived on country and record these observations in the box below. Look (what you saw) Hear (what you heard) I wonder… (questions to ask an expert or investigate back at school ) Bunjil Soundscapes Waa Information from education Mindi officers Signs about plant uses Dreaming stories at feature shows Signs about animal dreaming Information about Wurundjeri stories Seasons Sculptures Didjeridoo Scar Tree Bark Canoe Gunyah Information about Coranderrk William Barak sculpture Information about William Barak Artefacts (eg eel trap, marngrook, possum skin cloak) 1. Identify and explain how did indigenous people impact upon their environment? Indigenous people changed the landscape using fire stick farming which also assisted hunting Aboriginal people used their knowledge of the seasons to optimise hunting, gathering, eel farming and more Aboriginal people used organic local materials to create tools to assist them with hunting and gathering their food i.e. eel traps, woven grass baskets, rock fish traps etc. They only ever took what they needed from the land and had a deep respect and spiritual connection to the land and their surroundings. 2. How are humans impacting on natural resources in today’s society? How does this affect wildlife? When the land is disrespected, damaged or destroyed, this can have real impact on the wellbeing of people, plants and animals. European settlers and modern day humans have caused land degradation by: •Introducing poor farming practices causing land degradation •Introducing noxious weeds •Changing water flow courses and draining wetlands •Introducing feral animals •Destroying habitat through urbanization, logging and farming practices 3. -

Melbourne-Dreaming-Intro 1.Pdf (Pdf, 1.91

ABOUT THIS BOOK Melbourne Dreaming is both a guide book and social history of Melbourne, and the events and cultural traditions that have shaped local Aboriginal people’s lives. It aims to show where to look to gain a better understanding of the rich heritage and complex culture of Aboriginal people in Melbourne both before and since colonisation. It was first published in 1997. This is a completely updated and expanded edition. Melbourne Dreaming provides practical information on visiting both historical and contemporary sites located in the city centre, surrounding suburbs and outer areas. Arranged into seven precincts, Melbourne Dreaming takes you to beaches, parklands, camping places, historical sites, exhibitions, cultural displays and buildings. For Melbourne’s Aboriginal people the landscape prior to European settlement over which we travel was the face of the divine — the imprint of the ancestral creation beings that shaped the landscape on their epic journeys. Exploring Melbourne’s Aboriginal places is a way of paying respect to this sacred tradition while learning more about our shared and ancient history. Sites include locations and traces of important places before European settlement in 1835 such as shell middens, scarred trees, wells, fish traps, mounds and quarries. Other sites describe critical events that occurred because of the impact of European settlement. More recent places are the focus of contemporary life. What these places share in common is that each illustrates an important part of the overall story of the first inhabitants, the Kulin. Stories and photographs of some places of interest which have restricted access or cannot be visited have also been included. -

Benevolent Colonizers in Nineteenth-Century Australia Quaker Lives and Ideals

Benevolent Colonizers in Nineteenth-Century Australia Quaker Lives and Ideals Eva Bischoff Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series Series Editors Richard Drayton Department of History King’s College London London, UK Saul Dubow Magdalene College University of Cambridge Cambridge, UK The Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies series is a collection of studies on empires in world history and on the societies and cultures which emerged from colonialism. It includes both transnational, comparative and connective studies, and studies which address where particular regions or nations participate in global phenomena. While in the past the series focused on the British Empire and Commonwealth, in its current incarna- tion there is no imperial system, period of human history or part of the world which lies outside of its compass. While we particularly welcome the first monographs of young researchers, we also seek major studies by more senior scholars, and welcome collections of essays with a strong thematic focus. The series includes work on politics, economics, culture, literature, science, art, medicine, and war. Our aim is to collect the most exciting new scholarship on world history with an imperial theme. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/13937 Eva Bischoff Benevolent Colonizers in Nineteenth- Century Australia Quaker Lives and Ideals Eva Bischoff Department of International History Trier University Trier, Germany Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series ISBN 978-3-030-32666-1 ISBN 978-3-030-32667-8 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32667-8 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive licence to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2020 This work is subject to copyright. -

Your Candidates Metropolitan

YOUR CANDIDATES METROPOLITAN First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria Election 2019 “TREATY TO ME IS A RECOGNITION THAT WE ARE THE FIRST INHABITANTS OF THIS COUNTRY AND THAT OUR VOICE BE HEARD AND RESPECTED” Uncle Archie Roach VOTING IS OPEN FROM 16 SEPTEMBER – 20 OCTOBER 2019 Treaties are our self-determining right. They can give us justice for the past and hope for the future. The First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria will be our voice as we work towards Treaties. The First Peoples’ Assembly of Victoria will be set up this year, with its first meeting set to be held in December. The Assembly will be a powerful, independent and culturally strong organisation made up of 32 Victorian Traditional Owners. If you’re a Victorian Traditional Owner or an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander person living in Victoria, you’re eligible to vote for your Assembly representatives through a historic election process. Your voice matters, your vote is crucial. HAVE YOU ENROLLED TO VOTE? To be able to vote, you’ll need to make sure you’re enrolled. This will only take you a few minutes. You can do this at the same time as voting, or before you vote. The Assembly election is completely Aboriginal owned and independent from any Government election (this includes the Victorian Electoral Commission and the Australian Electoral Commission). This means, even if you vote every year in other elections, you’ll still need to sign up to vote for your Assembly representatives. Don’t worry, your details will never be shared with Government, or any electoral commissions and you won’t get fined if you decide not to vote. -

Sorry Day Is a Day Where We Remember the Stolen Generations

Aboriginal Heritage Office Yarnuping Education Series Ku-ring-gai, Lane Cove, North Sydney, Northern Beaches, Strathfield and Willoughby Councils © Copyright Aboriginal Heritage Office www.aboriginalheritage.org Yarnuping 5 Sorry Day 26th May 2020 Karen Smith Education Officer Sorry Day is a day where we remember the Stolen Generations. Protection & Assimilation Policies Have communities survived the removal of children? The systematic removal and cultural genocide of children has an intergenerational, devastating effect on families and communities. Even Aboriginal people put into the Reserves and Missions under the Protectionist Policies would hide their children in swamps or logs. Families and communities would colour their faces to make them darker. Not that long after the First Fleet arrived in 1788, a large community of mixed ancestry children could be found in Sydney. They were named ‘Friday’, ‘Johnny’, ‘Betty’, and denied by their white fathers. Below is a writing by David Collins who witnessed this occurring: “The venereal disease also has got among them, but I fear our people have to answer for that, for though I believe none of our women had connection with them, yet there is no doubt that several of the Black women had not scrupled to connect themselves with the white men. Of the certainty of this extraordinary instance occurred. A native woman had a child by one of our people. On its coming into the world she perceived a difference in its colour, for which not knowing how to account, she endeavoured to supply by art what she found deficient in nature, and actually held the poor babe, repeatedly over the smoke of her fire, and rubbed its little body with ashes and dirt, to restore it to the hue with which her other children has been born. -

Intimacies of Violence in the Settler Colony Economies of Dispossession Around the Pacific Rim

Cambridge Imperial & Post-Colonial Studies INTIMACIES OF VIOLENCE IN THE SETTLER COLONY ECONOMIES OF DISPOSSESSION AROUND THE PACIFIC RIM EDITED BY PENELOPE EDMONDS & AMANDA NETTELBECK Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series Series Editors Richard Drayton Department of History King’s College London London, UK Saul Dubow Magdalene College University of Cambridge Cambridge, UK The Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies series is a collection of studies on empires in world history and on the societies and cultures which emerged from colonialism. It includes both transnational, comparative and connective studies, and studies which address where particular regions or nations participate in global phenomena. While in the past the series focused on the British Empire and Commonwealth, in its current incarna- tion there is no imperial system, period of human history or part of the world which lies outside of its compass. While we particularly welcome the first monographs of young researchers, we also seek major studies by more senior scholars, and welcome collections of essays with a strong thematic focus. The series includes work on politics, economics, culture, literature, science, art, medicine, and war. Our aim is to collect the most exciting new scholarship on world history with an imperial theme. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/13937 Penelope Edmonds Amanda Nettelbeck Editors Intimacies of Violence in the Settler Colony Economies of Dispossession around the Pacific Rim Editors Penelope Edmonds Amanda Nettelbeck School of Humanities School of Humanities University of Tasmania University of Adelaide Hobart, TAS, Australia Adelaide, SA, Australia Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series ISBN 978-3-319-76230-2 ISBN 978-3-319-76231-9 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-76231-9 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018941557 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2018 This work is subject to copyright. -

Anthropology of Indigenous Australia

Anthropology of Indigenous Australia Class code ANTH-UA 9037 – 001 Instructor Petronella Vaarzon-Morel Details [email protected] Consultations by appointment. Please allow at least 24 hours for your instructor to respond to your emails. Class Details Fall 2017 Anthropology of Indigenous Australia Tuesday 12:30 – 3:30pm 5 September to 12 December Room 202 NYU Sydney Academic Centre Science House: 157-161 Gloucester Street, The Rocks 2000 Prerequisites None. Class This course offers an introduction to some of the classical and current issues in the Description anthropology of Indigenous Australia. The role of anthropology in the representation and governance of Indigenous life is itself an important subject for anthropological inquiry, considering that Indigenous people of Australia have long been the objects of interest and imagination by outsiders for their cultural formulations of kinship, ritual, art, gender, and politics. These representations—in feature films about them (such as Rabbit-Proof Fence and Australia), New Age Literature (such as Mutant Message Down Under), or museum exhibitions (such as in the Museum of Sydney or the Australian Museum)—are now also in dialogue with Indigenous forms of cultural production, in genres as diverse as film, television, drama, dance, art and writing. The course will explore how Aboriginal people have struggled to reproduce themselves and their traditions on their own terms, asserting their right to forms of cultural autonomy and self-determination. Through the examination of ethnographic and historical texts, films, archives and Indigenous life-writing accounts, we will consider the ways in which Aboriginalities are being challenged and constructed in contemporary Australia. -

3 Researchers and Coranderrk

3 Researchers and Coranderrk Coranderrk was an important focus of research for anthropologists, archaeologists, naturalists, historians and others with an interest in Australian Aboriginal people. Lydon (2005: 170) describes researchers treating Coranderrk as ‘a kind of ethno- logical archive’. Cawte (1986: 36) has argued that there was a strand of colonial thought – which may be characterised as imperialist, self-congratulatory, and social Darwinist – that regarded Australia as an ‘evolutionary museum in which the primi- tive and civilised races could be studied side by side – at least while the remnants of the former survived’. This chapter considers contributions from six researchers – E.H. Giglioli, H.N. Moseley, C.J.D. Charnay, Rev. J. Mathew, L.W.G. Büchner, and Professor F.R. von Luschan – and a 1921 comment from a primary school teacher, named J.M. Provan, who was concerned about the impact the proposed closure of Coranderrk would have on the ability to conduct research into Aboriginal people. Ethel Shaw (1949: 29–30) has discussed the interaction of Aboriginal residents and researchers, explaining the need for a nuanced understanding of the research setting: The Aborigine does not tell everything; he has learnt to keep silent on some aspects of his life. There is not a tribe in Australia which does not know about the whites and their ideas on certain subjects. News passes quickly from one tribe to another, and they are quick to mislead the inquirer if it suits their purpose. Mr. Howitt, Mr. Matthews, and others, who made a study of the Aborigines, often visited Coranderrk, and were given much assistance by Mr. -

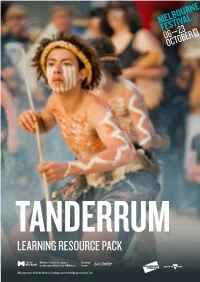

Learning Resource Pack

TANDERRUM LEARNING RESOURCE PACK Melbourne Festival’s free program Presenting proudly supported by the City of Melbourne Partner With support from VicHealth, Newsboys Foundation and the Helen Macpherson Smith Trust TANDERRUM LEARNING RESOURCE PACK INTRODUCTION STATEMENT FROM ILBIJERRI THEATRE COMPANY Welcome to the study guide of the 2016 Melbourne Festival production of ILBIJERRI (pronounced ‘il BIDGE er ree’) is a Woiwurrung word meaning Tanderrum. The activities included are related to the AusVELS domains ‘Coming Together for Ceremony’. as outlined below. These activities are sequential and teachers are ILBIJERRI is Australia’s leading and longest running Aboriginal and encouraged to modify them to suit their own curriculum planning and Torres Strait Islander Theatre Company. the level of their students. Lesson suggestions for teachers are given We create challenging and inspiring theatre creatively controlled by within each activity and teachers are encouraged to extend and build on Indigenous artists. Our stories are provocative and affecting and give the stimulus provided as they see fit. voice to our unique and diverse cultures. ILBIJERRI tours its work to major cities, regional and remote locations AUSVELS LINKS TO CURRICULUM across Australia, as well as internationally. We have commissioned 35 • Cross Curriculum Priorities: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander new Indigenous works and performed for more than 250,000 people. History and Cultures We deliver an extensive program of artist development for new and • The Arts: Creating and making, Exploring and responding emerging Indigenous writers, actors, directors and creatives. • Civics and Citizenship: Civic knowledge and Born from community, ILBIJERRI is a spearhead for the Australian understanding, Community engagement Indigenous community in telling the stories of what it means to be Indigenous in Australia today from an Indigenous perspective. -

Rural Ararat Heritage Study Volume 4

Rural Ararat Heritage Study Volume 4. Ararat Rural City Thematic Environmental History Prepared for Ararat Rural City Council by Dr Robyn Ballinger and Samantha Westbrooke March 2016 History in the Making This report was developed with the support PO Box 75 Maldon VIC 3463 of the Victorian State Government RURAL ARARAT HERITAGE STUDY – VOLUME 4 THEMATIC ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY Table of contents 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 The study area 1 1.2 The heritage significance of Ararat Rural City's landscape 3 2.0 The natural environment 4 2.1 Geomorphology and geology 4 2.1.1 West Victorian Uplands 4 2.1.2 Western Victorian Volcanic Plains 4 2.2 Vegetation 5 2.2.1 Vegetation types of the Western Victorian Uplands 5 2.2.2 Vegetation types of the Western Victoria Volcanic Plains 6 2.3 Climate 6 2.4 Waterways 6 2.5 Appreciating and protecting Victoria’s natural wonders 7 3.0 Peopling Victoria's places and landscapes 8 3.1 Living as Victoria’s original inhabitants 8 3.2 Exploring, surveying and mapping 10 3.3 Adapting to diverse environments 11 3.4 Migrating and making a home 13 3.5 Promoting settlement 14 3.5.1 Squatting 14 3.5.2 Land Sales 19 3.5.3 Settlement under the Land Acts 19 3.5.4 Closer settlement 22 3.5.5 Settlement since the 1960s 24 3.6 Fighting for survival 25 4.0 Connecting Victorians by transport 28 4.1 Establishing pathways 28 4.1.1 The first pathways and tracks 28 4.1.2 Coach routes 29 4.1.3 The gold escort route 29 4.1.4 Chinese tracks 30 4.1.5 Road making 30 4.2 Linking Victorians by rail 32 4.3 Linking Victorians by road in the 20th