URBAN LIFE in MUGHAL GUJARAT Ifla^Ttr of Piitlofiiopiip

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012

Copyright by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India Committee: _____________________ Gail Minault, Supervisor _____________________ Cynthia Talbot _____________________ William Roger Louis _____________________ Janet Davis _____________________ Douglas Haynes Princes, Diwans and Merchants: Education and Reform in Colonial India by Aarti Bhalodia-Dhanani, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2012 For my parents Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without help from mentors, friends and family. I want to start by thanking my advisor Gail Minault for providing feedback and encouragement through the research and writing process. Cynthia Talbot’s comments have helped me in presenting my research to a wider audience and polishing my work. Gail Minault, Cynthia Talbot and William Roger Louis have been instrumental in my development as a historian since the earliest days of graduate school. I want to thank Janet Davis and Douglas Haynes for agreeing to serve on my committee. I am especially grateful to Doug Haynes as he has provided valuable feedback and guided my project despite having no affiliation with the University of Texas. I want to thank the History Department at UT-Austin for a graduate fellowship that facilitated by research trips to the United Kingdom and India. The Dora Bonham research and travel grant helped me carry out my pre-dissertation research. -

Narrating North Gujarat: a Study of Amrut Patel's

NARRATING NORTH GUJARAT: A STUDY OF AMRUT PATEL’S CONTRIBUTION TO FOLK LITERATURE A MINOR RESEARCH PROJECT :: SUBMITTED TO :: UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION :: SUBMITTED BY :: DR.RAJESHKUMAR A. PATEL ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR SMT.R.R.H.PATEL MAHILA ARTS COLLEGE, VIJAPUR DIST.MEHSANA (GUJARAT) 2015 Preface Literature reflects human emotions, thoughts and expressions. It’s a record of activities and abstract ideas of human beings. The oral tradition of literature is the aspect of literature passing ideas and feelings mouth to mouth. I’ve enjoyed going through the precious and rare pieces of folk literature collected and edited by Amrut Patel. I congratulate and salute Amrut Patel for rendering valuable service to this untouchable, vanishing field of civilization. His efforts to preserve the vanishing forms of oral tradition stand as milestone for future generation and students of folk literature. I am indebted to UGC for sanctioning the project. The principal of my college, Dr.Sureshbhai Patel and collegues have inspired me morally and intellectually. I thank them. I feel gratitude to Nanabhai Nadoda for uploding my ideas and making my work easy. Shaileshbhai Paramar, the librarian has extended his time and help, I thank him. Shri Vishnubhai M.Patel, Shri R.R.Ravat, Shri.D.N.Patel, Shri S.M.Patel, Shri R.J.Brahmbhatt, Shri J.J.Rathod., Shri D.S.Kharadi, B.L.Bhangi and Maheshbhai Limbachiya have suppoted me morally. I thank them all. DR.Rajeshkumar A.Patel CONTENTS 1. Introduction: 1.1 North Gujarat 1.2 Life and Works of Dr.Amrut Patel 1.3 Folk Literature-An Overview 2. -

Chapter VI Conclusions

Chapter VI Conclusions Trade and commerce of Adil Shahi Sultanate was gradually increasing through various stages, but it reached to a height after the fall of Barid Shahi and Vijaynagar. The establishment of Bahmani rule had removed Bijapur’s status as a remote frontier post, however, under the Bahamanis Bijapur never possessed the economic or political importance of Gulbarga and Bidar, the two Bahmani capitals. Bijapur’s de facto independence (1490), from Bahmani authority could not suddenly transform the city into a notable centre of Islamic civilization. One political city had to fall or decline so that a new political city rose and grew in its stead. Bidar was declined in the last quarter of 15th century and Vijaynagar was destroyed by confederate Muslim states of the Deccan in the battle of Talikota in 1565 and on its ashes raised the glory of Bijapur. By the end of sixteenth century Bijapur had emerged as one of the major Islamic urban centres. The early seventeenth century saw the peak growth of the city’s population, on the basis of the estimation of James Campbell, two million of population was resided within and outside of fort of Bijapur. Under the aegis of Ibrahim II and Muhammad Adil Shah, Bijapur’s significance in all respects grew further and it became an important city of the Deccan. Migration of Qadiri Sufis into the Bijapur during this period could be seen as an important indicator of urbanization. After the fall of Vijaynagar the resources of sultanate increases and Karwar, Honawar and Bhatkal came in their possession which helps to boost up their trade and 548 J.D.B., Gribble, History of the Deccan, op. -

1 Title: Enlightenment and Empire, Mughals and Marathas: The

Title: Enlightenment and Empire, Mughals and Marathas: The Religious History of Indian in the Work of East India Company Servant, Alexander Dow. Abstract: This article situates the work of East India Company servant Alexander Dow (1735-1779), principally his writings on the history and future state of India, in contemporary debates about empire, religion and enlightened government. To do so it offers a sustained analysis of his 1772 essay “A Dissertation Concerning the Origin and Nature of Despotism in Hindostan”, as well as his proposals for the restoration of Bengal, both of which played an influential part in shaping the preoccupations with Mughal history that dominated the contemporary crisis in the Company’s legitimacy. By linking these texts to his earlier work on ‘Hindoo’ religion, it will argue that Dow’s analysis of the relationship between certain religious cultures and their civic qualities was rooted in a deist perspective. It doing so it restores the enlightenment components of Dow’s thought, and their impact on the ideology of empire, in a crucial period of British expansion in India. Keywords: Empire, Enlightenment, India, Eighteenth Century, East India Company, Religion 1 Historians are increasingly concerned with the Enlightenment’s extra-European context.1 In particular, recognising that international commerce and exchange were its material context, scholars have turned their attention to Enlightenment attitudes to empire. For Sankar Muthu this has meant tracing anti-imperialist strands of enlightenment thought.2 This -

Reaching the Least Reached CCBA

CENTRAL COAST BAPTIST ASSOCIATION Reaching the Least Reached What is an unreached people Where do UPGs live? What are the largest unreached and an unengaged people people groups in the Bay Area? group? It will be a surprise to some people that some large, very Nobody knows for certain yet A people group is unreached unreached people groups live in the which the largest UPGs are in the Bay when the number of evangelical United States, and even within the Area, but we do know which of them Christians is less than 2% of its geography of the Central Coast are the largest in the world. We also population (UPG). It is further called Baptist Association. They represent know some of them that are certainly unengaged (UUPG) when there is no various regions of the world such as here in large numbers, mostly in Santa church planting methodology China, India and the Middle East. Clara, Alameda, San Francisco, San consistent with evangelical faith and They are adherents of world religions Mateo and Contra Costa counties. practice under way. “A people group such as Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, There are more UPGs here than there is not engaged when it has been Sikhism and Jainism. can ever be paid missionaries to work merely adopted, is the object of among them. It will take ordinary focused prayer, or is part of an Christians who are willing to pray and advocacy strategy.” (IMB) work in extraordinary ways so that Today there are 6,430 unreached people from every nation, tribe, and people groups around the world. -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Texts, Tombs and Memory: The Migration, Settlement and Formation of a Learned Muslim Community in Fifteenth-Century Gujarat Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/89q3t1s0 Author Balachandran, Jyoti Gulati Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Texts, Tombs and Memory: The Migration, Settlement, and Formation of a Learned Muslim Community in Fifteenth-Century Gujarat A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Jyoti Gulati Balachandran 2012 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Texts, Tombs and Memory: The Migration, Settlement, and Formation of a Learned Muslim Community in Fifteenth-Century Gujarat by Jyoti Gulati Balachandran Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2012 Professor Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Chair This dissertation examines the processes through which a regional community of learned Muslim men – religious scholars, teachers, spiritual masters and others involved in the transmission of religious knowledge – emerged in the central plains of eastern Gujarat in the fifteenth century, a period marked by the formation and expansion of the Gujarat sultanate (c. 1407-1572). Many members of this community shared a history of migration into Gujarat from the southern Arabian Peninsula, north Africa, Iran, Central Asia and the neighboring territories of the Indian subcontinent. I analyze two key aspects related to the making of a community of ii learned Muslim men in the fifteenth century - the production of a variety of texts in Persian and Arabic by learned Muslims and the construction of tomb shrines sponsored by the sultans of Gujarat. -

Read Magazine

Trendy Travel Trade with Food & Shop Volume VIII • Issue I • February 2021 • Pages 88 • Rs.100/- Experience Spirituality, Faith and Culture #LadyBoss Kutch: A Land of White Desert Royal Journey of India Archaeological Tour of Majestic Kerala Enchanting Himalayas Tribal Trail Buddhist Temple with 18 to 20 Nights Rajasthan 14 to 15 Nights with Taj 15 to 17 Nights North East India Tour Mumbai – Mangalore – Bekal – Wayanad Bhubaneswar - Dangmal - Bhubaneswar 21 to 23 Nights 13 to 15 Nights 14 to 16 Nights Delhi - Jaipur - Pushkar – Ranthambore – Kozhikode(Calicut) - Baliguda Delhi – Jaipur – Samode – Nawalgarh – Delhi - Agra - Darjeeling - Gangtok - Delhi - Varanasi -Bodhgaya - Patna Sawai Madhopur – Kota – Cochin – Thekkady – Kumarakom– - Rayagada - Jeypore - Rayagada - Bikaner – Gajner – Jaisalmer – Osian Phuntsholing - Thimphu - Punakha - -Kolkata - Bagdogara - Darjeeling - Bundi - Chittorgarh - Bijaipur - Quilon – Varkala – Kovalam Gopalpur - Puri – Bhubaneswar Udaipur - Kumbalgarh - Jodhpur - – Khimsar – Manvar – Jodhpur – Rohet – Paro - Delhi - Pelling (Pemayangtse)- Gangtok - Jaisalmer - Bikaner - Mandawa – Delhi Mount Abu – Udaipur – Dungarpur Kalimpong -Bagdogra – Delhi – Deogarh – Ajmer – Pushkar – Pachewar – Ranthambhore – Agra – Delhi Contact @ :+91- 9899359708, 9999683737, info@ travokhohlidays.com, [email protected], www.travok.net EXPERIENCEHingolga HERITAGE & NATURE ATdh ITS BEST A Hidden Gem of Gujarat Just 70 kms away from Rajkot is a unique sanctuary which not only offers the grandeur of a royal era but also nature's treasures. Explore the magnicent Hingolgadh palace surrounded by a scenic sanctuary that is home to the Chinkara, Wolf, Jackal, Fox, Porcupine, Hyena, Indian Pitta and 230 species of birds. So this weekend, have a royal experience and some wild adventure. Disclaimer: The details and pictures contained here are for information and could be indicative. -

The Color Festival of Bikaner, Rajasthan

1 Prof. Amarika Singh Vice Chancellor Mohanlal Sukhadia University Udaipur, Rajasthan, India No.PSVC/MLSU/Message/2021 Dated 8th June, 2021 MESSAGE I am glad to know that the Department of History, Mohanlal Sukhadia University, Udaipur, in collaboration with Indus International Research Foundation, New Delhi, is organizing an Intemational Webinar on "Holi : A Custodian of Vibrant Indian Values and Culture" on 11 th and 12 th June 2021, and an E-Souvenir will be released on this occasion. I hope that the deliberation of the Webinar will help in revealing unique traditions of celebrating Holi Festival in India and by Indians living abroad. I wish the Webinar a grand success. (Prof. Amarika Singh) Vice Chancellor 2 Col. (Dr.) Vijaykant Chenji President Indus International Research Foundation New Delhi, India Dated 8th June, 2021 MESSAGE India is a multicultural nation with rich traditions and customs. Inspite of its diversity there is a common thread that runs through its multilingual, multi ethnic societies, connecting them to form a beautiful necklace. The festivals of India are celebrated each year with great deal of enthusiasm and fervour. These are associated with change of seasons and bring freshness and vibrancy to our spirit of life. One such event is Holi, the festival of colours. It is normally celebrated on the full moon day of March. Although Holi celbrated in Rajasthan, Mathura, Awadh and Varanasi are internationally known, Holi is also celebrated across other parts of India in the West, South and East too. They are known by different names and modus of celebrations vary. But at the heart, the theme remains the same - Triumph of Right over evil. -

Cultural Negotiations in Health and Illness

Diversity in Health and Care 2009;6:xxx–xxx # 2009 Radcliffe Publishing Research paper Cultural negotiations in health and illness: the experience of type 2 diabetes among Gujarati-speaking South Asians in England Harshad Keval Lecturer, School of Human and Life Sciences, Roehampton University, London, UK What is known on this subject . We know that South Asian communities in the UK have a higher risk of type 2 diabetes than white British people. Current health policy and research indicate that there are deficits in education and knowledge about the best ways to manage diet, exercise and medication within South Asian communities. There is much potential for exploring in depth understandings of the lived experience of diabetes within South Asian communities, to complement the existing knowledge base. What this paper adds . This study indicates that, as health science discourse often uses a combination of genetic, cultural and lifestyle factors to explain high rates of diabetes, there is a parallel and related construction of a South Asian diabetes risk. Using qualitative in-depth methods to explore the study participants’ experiences, it is possible to identify how health and illness are situated within complex social, cultural and biographical frameworks. It is possible to look beyond constructions of diabetes risk towards the way participants with diabetes utilise their life experience, their history and their social and cultural community to manage their condition. In doing so they demonstrate a form of resistance to the constructions of diabetes risk that can be imposed by health science discourse. This paper shows how their ethnic and cultural identities are often invoked in dynamic and flexible ways to help them to deal with their condition. -

Chapter Preview

As per Model CBCS Syllabus HISTORY OF INDIA-V [C.1526-1750] Core Paper IX Semester-IV Dr. Abhijit Sahoo Lecturer in History Shishu Ananta Mahavidyalaya, Balipatna, Khordha, Odisha ISO 9001:2015 CERTIFIED © Author No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording and/or otherwise without the prior written permission of the author and the publisher. First Edition : 2021 Published by : Mrs. Meena Pandey for Himalaya Publishing House Pvt. Ltd., “Ramdoot”, Dr. Bhalerao Marg, Girgaon, Mumbai - 400 004. Phone: 022-23860170, 23863863; Fax: 022-23877178 E-mail: [email protected]; Website: www.himpub.com Branch Offices : New Delhi : “Pooja Apartments”, 4-B, Murari Lal Street, Ansari Road, Darya Ganj, New Delhi - 110 002. Phone: 011-23270392, 23278631; Fax: 011-23256286 Nagpur : Kundanlal Chandak Industrial Estate, Ghat Road, Nagpur - 440 018. Phone: 0712-2721215, 3296733; Telefax: 0712-2721216 Bengaluru : Plot No. 91-33, 2nd Main Road, Seshadripuram, Behind Nataraja Theatre, Bengaluru - 560 020. Phone: 080-41138821; Mobile: 09379847017, 09379847005 Hyderabad : No. 3-4-184, Lingampally, Besides Raghavendra Swamy Matham, Kachiguda, Hyderabad - 500 027. Phone: 040-27560041, 27550139 Chennai : New No. 48/2, Old No. 28/2, Ground Floor, Sarangapani Street, T. Nagar, Chennai - 600 017. Mobile: 09380460419 Pune : “Laksha” Apartment, First Floor, No. 527, Mehunpura, Shaniwarpeth (Near Prabhat Theatre), Pune - 411 030. Phone: 020-24496323, 24496333; Mobile: 09370579333 Lucknow : House No. 731, Shekhupura Colony, Near B.D. Convent School, Aliganj, Lucknow - 226 022. Phone: 0522-4012353; Mobile: 09307501549 Ahmedabad : 114, “SHAIL”, 1st Floor, Opp. -

Stranded Persons List from Gujarat to Manipur Current Current Person in Sl No

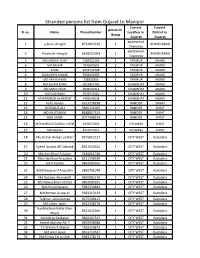

Stranded persons list from Gujarat to Manipur Current Current person in Sl no. Name PhoneNumber Location in District in Group Gujarat Gujarat applewood 1 juliana shinglai 8732015246 1 AHMEDABAD Township applewood 2 Rinchuila shinglai 6358212054 1 AHMEDABAD Township 3 MOHADDAD SHAFI 7383021363 1 TARAPUR ANAND 4 MD BASHIR 7041660692 1 TARAPUR ANAND 5 AFZAL 9429745368 1 TARAPUR ANAND 6 SLIMUDDIN MAKAK 9366464969 1 TARAPUR ANAND 7 MD YAHYA KHAN 738302066 1 TARAPUR ANAND 8 MD ASLAM KHAN 9023861796 1 KHAMBHAT ANAND 9 MD SAROJ KHAN 6009130314 1 KHAMBHAT ANAND 10 MD SULEIMAN 9558737681 1 KHAMBHAT ANAND 11 MUHAMMED SHAHADAT 7486096838 1 KHAMBHAT ANAND 12 hafiz rizwan 6353278298 1 RANDER SURAT 13 SIDDIQUE ALI 9366171005 1 RANDER SURAT 14 MD MUSTAKIM 8488857313 1 RANDER SURAT 15 MM SARIF 9077368234 1 RANDER SURAT 16 MOHAMMAD SAMSUL HAQE 9402620463 1 KOSAMBA SURAT 17 MD RAHISH 8414070711 1 KOSAMBA SURAT 18 Mo.Kamal Akman pathan 8575812127 1 CITY WEST Vadodara 19 Syeed Liyakat Ali Tabarak 8567610162 1 CITY WEST Vadodara 20 Md.Anis Khan A.Kasim 7630051746 1 CITY WEST Vadodara 21 Md.IrfanKhan Feijuddin 8511296539 1 CITY WEST Vadodara 22 Altaf Tomba 9862945355 1 CITY WEST Vadodara 23 Md.Nawaj sarif Feijuddin 9856761078 1 CITY WEST Vadodara 24 Md.Rezwan Ahamed R 9856983176 1 CITY WEST Vadodara 25 Md.Nawaj khan Tomba 9862945355 1 CITY WEST Vadodara 26 Md.Anish Ibosana 9383350481 1 CITY WEST Vadodara 27 Md.Noman Asrap ali 9383213129 1 CITY WEST Vadodara 28 Tajkhan abdulsamad 8575509412 1 CITY WEST Vadodara 29 Md.Juber Jamir 9612338278 1 CITY WEST Vadodara Yumkhaibam Rahis Khan 30 9612621666 1 CITY WEST Vadodara Ithem 31 Md.Mirza Soukatali 9856407547 1 CITY WEST Vadodara 32 Syeed sikandar Ali T 6909958988 1 CITY WEST Vadodara 33 Th Wasim A.Manal 7306216873 1 CITY WEST Vadodara 34 Md.Amir Ayub 9612719347 1 CITY WEST Vadodara 35 Md.Firdos Feroj shkh 9383278174 1 CITY WEST Vadodara 36 Syeed sultan Alam T 8132028700 1 CITY WEST Vadodara 37 Mo.sufiyan Islauddin 6239023946 1 CITY WEST Vadodara 38 Mo.Musaraf Salaodin 8974788491 1 CITY WEST Vadodara 39 W.