The Royal Engineers Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Night Operation on the Passchendaele Ridge, 2Nd December 1917

Centre for First World War Studies A Moonlight Massacre: The Night Operation on the Passchendaele Ridge, 2nd December 1917 by Michael Stephen LoCicero Thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts & Law June 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The Third Battle of Ypres was officially terminated by Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig with the opening of the Battle of Cambrai on 20 November 1917. Nevertheless, a comparatively unknown set-piece attack – the only large-scale night operation carried out on the Flanders front during the campaign – was launched twelve days later on 2 December. This thesis, a necessary corrective to published campaign narratives of what has become popularly known as „Passchendaele‟, examines the course of events from the mid-November decision to sanction further offensive activity in the vicinity of Passchendaele village to the barren operational outcome that forced British GHQ to halt the attack within ten hours of Zero. A litany of unfortunate decisions and circumstances contributed to the profitless result. -

Two Diplomas Awarded to George Joseph Bell Now in the Possession of the Royal Medical Society

Res Medica, Volume 268, Issue 2, 2005 Page 1 of 6 Two Diplomas Awarded to George Joseph Bell now in the Possession of the Royal Medical Society Matthew H. Kaufman Professor of Anatomy, Honorary Librarian of the Royal Medical Society Abstract The two earliest diplomas in the possession of the Royal Medical Society were both awarded to George Joseph Bell, BA Oxford. One of these diplomas was his Extraordinary Membership Diploma that was awarded to him on 5 April 1839. Very few of these Diplomas appear to have survived, and the critical introductory part of his Diploma is inscribed as follows: Ingenuus ornatissimusque Vir Georgius Jos. Bell dum socius nobis per tres annos interfuit, plurima eademque pulcherrima, hand minus ingenii f elicis, quam diligentiae insignis, animique ad optimum quodque parati, exempla in medium protulit. In quorum fidem has literas, meritis tantum concessus, manibus nostris sigilloque munitas, discedenti lubentissime donatus.2 Edinburgi 5 Aprilis 1839.3 Copyright Royal Medical Society. All rights reserved. The copyright is retained by the author and the Royal Medical Society, except where explicitly otherwise stated. Scans have been produced by the Digital Imaging Unit at Edinburgh University Library. Res Medica is supported by the University of Edinburgh’s Journal Hosting Service url: http://journals.ed.ac.uk ISSN: 2051-7580 (Online) ISSN: ISSN 0482-3206 (Print) Res Medica is published by the Royal Medical Society, 5/5 Bristo Square, Edinburgh, EH8 9AL Res Medica, Volume 268, Issue 2, 2005: 39-43 doi:10.2218/resmedica.v268i2.1026 Kaufman, M. H, Two Diplomas Awarded to George Joseph Bell now in the Possession of the Royal Medical Society, Res Medica, Volume 268, Issue 2 2005, pp.39-43 doi:10.2218/resmedica.v268i2.1026 Two Diplomas Awarded to George Joseph Bell now in the Possession of the Royal Medical Society MATTHEW H. -

Former Fellows Biographical Index Part

Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 Biographical Index Part Two ISBN 0 902198 84 X Published July 2006 © The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street, Edinburgh, EH2 2PQ BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF FORMER FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH 1783 – 2002 PART II K-Z C D Waterston and A Macmillan Shearer This is a print-out of the biographical index of over 4000 former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh as held on the Society’s computer system in October 2005. It lists former Fellows from the foundation of the Society in 1783 to October 2002. Most are deceased Fellows up to and including the list given in the RSE Directory 2003 (Session 2002-3) but some former Fellows who left the Society by resignation or were removed from the roll are still living. HISTORY OF THE PROJECT Information on the Fellowship has been kept by the Society in many ways – unpublished sources include Council and Committee Minutes, Card Indices, and correspondence; published sources such as Transactions, Proceedings, Year Books, Billets, Candidates Lists, etc. All have been examined by the compilers, who have found the Minutes, particularly Committee Minutes, to be of variable quality, and it is to be regretted that the Society’s holdings of published billets and candidates lists are incomplete. The late Professor Neil Campbell prepared from these sources a loose-leaf list of some 1500 Ordinary Fellows elected during the Society’s first hundred years. He listed name and forenames, title where applicable and national honours, profession or discipline, position held, some information on membership of the other societies, dates of birth, election to the Society and death or resignation from the Society and reference to a printed biography. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G. Phd, Mphil, Dclinpsychol) at the University of Edinburgh

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Beliefs and practices in health and disease from the Maclagan Manuscripts (1892–1903) Allan R Turner PhD – The University of Edinburgh – 2014 I, Allan Roderick Turner, Ph.D.student at Edinburgh University (s0235313) affirm that I have been solely responsible for the research in the thesis and its completion, as submitted today. Signed Date i Acknowledgements I am pleased to have the opportunity of expressing my gratitude to all the following individuals during the preparation and the completion of this thesis.My two earlier supervisors were Professor Donald.E.Meek and Dr. John. Shaw and from both teachers, I am pleased to acknowledge their skilled guidance and motivation to assist me during the initial stages of my work. My current supervisor, Dr.Neill Martin merits special recognition and thanks for continuing to support, encourage and direct my efforts during the demanding final phases. -

Past Presidents: the Maclagan Dynasty

M Telfer,A Lwin, P Jenkins respiratory failure. Thorax 2004; 59(12):1020–5. • Plant PK, Owen JL, Elliott MW. Non-invasive ventilation in acute • Plant PK, Elliott MW. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: long management of ventilatory failure in COPD. Thorax 2003; term survival and predictors of in-hospital outcome. Thorax 58(6):537–42. 2001; 56(9):708–12. PAST PRESIDENTS career much more distinguished and he was baptised by the same honourable than that of Lesassier. minister who had baptised Robert The Maclagan Dynasty Records show that, in addition to the Burns, but that is very unlikely. horrific wounds, major infections must In the history of the College, there have challenged him and his staff. Douglas, like his father, went to have been several instances when Edinburgh’s Royal High School and succeeding generations of one family Whether or not he was at Waterloo University, gaining his LRCSE in 1831, have been Fellows, even Presidents. in 1815 is not known. He returned followed by his FRCSEd and MD in Few have been Presidents of both to Edinburgh and set up in surgical 1833. After visiting Paris, Berlin and the Royal College of Physicians and practice in 1816, being elected London he returned to Edinburgh as Surgeons of Edinburgh before or FRCSEd in that same year, and an assistant to his father who by this since the MacLagan dynasty. becoming President in 1826. In 1828 time was a famous surgeon and he was elected a Fellow of the Royal academic. He must soon have David Maclagan (1785–1865) Society of Edinburgh and appointed realised that surgery was not his Surgeon-in-Ordinary to Her Majesty forte and he gave it up to lecture on Educated at the Royal High School of in Scotland in 1838. -

British 8Th Infantry Division on the Western Front, 1914-1918

Centre for First World War Studies British 8th Infantry Division on the Western Front, 1914-18 by Alun Miles THOMAS Thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts & Law January 2010 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT Recent years have seen an increasingly sophisticated debate take place with regard to the armies on the Western Front during the Great War. Some argue that the British and Imperial armies underwent a ‘learning curve’ coupled with an increasingly lavish supply of munitions, which meant that during the last three months of fighting the BEF was able to defeat the German Army as its ability to conduct operations was faster than the enemy’s ability to react. This thesis argues that 8th Division, a war-raised formation made up of units recalled from overseas, became a much more effective and sophisticated organisation by the war’s end. It further argues that the formation did not use one solution to problems but adopted a sophisticated approach dependent on the tactical situation. -

THE HOME of the ROYAL SOCIETY of EDINBURGH Figures Are Not Available

THE HOME OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH Figures are not available Charles D Waterston The bicentennial history of the Royal Society of Edinburgh1, like previous accounts, was rightly concerned to record the work and achievements of the Society and its Fellows. Although mention is made of the former homes and possessions of the Society, these matters were incidental to the theme of the history which was the advancement of learning and useful knowledge, the chartered objectives of the Society. The subsequent purchases by the Society of its premises at 22–28 George Street, Edinburgh, have revealed a need for some account of these fine buildings and of their contents for the information of Fellows and to enhance the interest of many who will visit them. The furniture so splendidly displayed in 22–24 George Street dates, for the most part, from periods in our history when the Society moved to more spacious premises, or when expansion and refurbishment took place within existing accommodation. In order that these periods of acquisition may be better appreciated it will be helpful to give a brief account of the rooms which it formerly occupied before considering the Society's present home. Having no personal knowledge of furniture, I acknowledge my indebtedness to Mr Ian Gow of the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland and Mr David Scarratt, Keeper of Applied Art at the Huntly House Museum of Edinburgh District Council Museum Service for examining the Society's furniture and for allowing me to quote extensively from their expert opinions. -

Royal Engineers Journal

0i r Z< 0c) M THE to ?d ROYAL ENGINEERS cn 1 >0 ?o JOURNAL Vol. LXXIII JUNE 1959 No. 2 CONTENTS Statues of Kitchener and Gordon Recently Repatriated from Khartoum . The Editor 116 The Gillois Assault Crossing Equipment . Major G. H. McCutcheon 118 The Lineburg Memorial Stone . Major-General Sir Eustace F. Tickell 130 Earth Movement Computations for Military Airfield Construction Lieut.-Colonel C. E.Warth 132 Loading and Unloading . Captain P. R. Knowles 143 The Trozina Project . Captain P. M. Lucas 156 Field Engineers in Atomic Warfare . Major A. E. Younger 163 Some Ideas for a New Field Squadron . Major J. D. Townsend-Rose 168 Maralinga . Lieut.-Colonel H. Harvey-Williams 175 The South Georgia Surveys . Captain A. G. Bomford 180 The Royal Engineers' Benevolent Fund . The Secretary of the Fund 189 Civilianization or the Twilight to a Military Career Lieut.-Colonel R. M. Power 195 Memoirs, Correspondence, Book Reviews, Technical Notes 200 _ PUB] ' EERS INSTITUTION OF RE OFFICE COPY All itruti DO NOT REMOVE Specialised Postal Coaching for the Army PRACTICAL AND WRITTEN Staff College and Promotion Examinations Specially devised Postal Courses to provide adequate practice for written and oral examnations-All maps supplied-Complete Model Answers to all Tests-Expert guidance by experienced Army Tutors-Authoritative Study Notes-Al Tuition conducted through the medium of the post-Air Mail to Officers overseas-Moderate fees payable by instalments. * * * ALSO INTENSIVE COMMERCIAL TRAINING FOR EMPLOYMENT ON RETIREMENT Write today for particulars and/or advice, stating examination or civilian career in which interested, to the Secretary, (M12), Metropolitan College, St. -

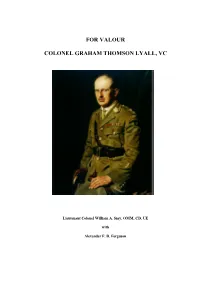

For Valour Colonel Graham Thomson Lyall, Vc

FOR VALOUR COLONEL GRAHAM THOMSON LYALL, VC Lieutenant Colonel William A. Smy, OMM, CD, UE with Alexander F. D. Ferguson Copyright © 2009 William Arthur Smy All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication, reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without the prior written permission is an infringement of the copyright law. Canadian Cataloguing Publication Data ISBN 978-0-9692232-1-4 Main Entry under Title: For Valour: Colonel Graham Thomson Lyall, VC One Volume Smy, William A., 1938 – For Valour: Colonel Graham Thomson Lyall, VC 1. World War I, 1914-1919. 2. Victoria Cross. 3. Canadian Expeditionary Force, 1914-1919. 4. British Army, North Africa, 1940-1942. I. Ferguson, Alexander F. D., 1928- II. Title CONTENTS Preface Acknowledgments A Note on Nomenclature and Usage and Abbreviations Early Life Canada The 19th “Lincoln” Regiment, 1914-1915 81st Battalion, Canadian Expeditionary Force, 1915-1916 4th Canadian Mounted Rifles, CEF, 1916-1917 The Somme, 1916 Arras, 1916 102nd Canadian Infantry Battalion, CEF, 1917-1919 Ypres, 1917 Arras, 1918 The Hindenburg Line and Bourlon Wood, 1918 Blécourt, 1 October 1918 The Victoria Cross The Canadian Reaction Scotland Demobilization, Investiture and Marriage The 1920 Garden Party at Buckingham Palace Scotland Again The 1929 Victoria Cross Dinner Domestic Life 1929-1939 The Vimy Pilgrimage, 1936 World War II, 1939-1941 North Africa Scotland Memorials Appendix 1 – Family Structure -

Former Fellows Biographical Index Part

Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 Biographical Index Part One ISBN 0 902 198 84 X Published July 2006 © The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street, Edinburgh, EH2 2PQ BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF FORMER FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH 1783 – 2002 PART I A-J C D Waterston and A Macmillan Shearer This is a print-out of the biographical index of over 4000 former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh as held on the Society’s computer system in October 2005. It lists former Fellows from the foundation of the Society in 1783 to October 2002. Most are deceased Fellows up to and including the list given in the RSE Directory 2003 (Session 2002-3) but some former Fellows who left the Society by resignation or were removed from the roll are still living. HISTORY OF THE PROJECT Information on the Fellowship has been kept by the Society in many ways – unpublished sources include Council and Committee Minutes, Card Indices, and correspondence; published sources such as Transactions, Proceedings, Year Books, Billets, Candidates Lists, etc. All have been examined by the compilers, who have found the Minutes, particularly Committee Minutes, to be of variable quality, and it is to be regretted that the Society’s holdings of published billets and candidates lists are incomplete. The late Professor Neil Campbell prepared from these sources a loose-leaf list of some 1500 Ordinary Fellows elected during the Society’s first hundred years. He listed name and forenames, title where applicable and national honours, profession or discipline, position held, some information on membership of the other societies, dates of birth, election to the Society and death or resignation from the Society and reference to a printed biography. -

Royal Engineers

Royal Engineers The Corps of Royal Engineers, usually just called the Royal Engineers (RE), and commonly Royal Engineers known as the Sappers, is one of the corps of the British Army. It provides military engineering and other technical support to the British Armed Forces and is headed by the Chief Royal Engineer. The Regimental Headquarters and the Royal School of Military Engineering are in Chatham in Kent, England. The corps is divided into several regiments, barracked at various places in the United Kingdom and around the world. Contents History Regimental museum Significant constructions Cap badge of the Corps of Royal British Columbia Engineers. Royal Albert Hall Indian infrastructure Active 1716–present Rideau Canal Country United Kingdom Dover's Western Heights Pentonville Prison Branch British Army Boundary Commissions Size 22 Regiments Abney Level Part of Commander Field Army H.M. Dockyards Chatham Dockyard Garrison/HQ Chatham, Kent, England Trades Motto(s) Ubique and Quo Fas et Units Gloria Ducunt Brigades & Groups ("Everywhere" and Regiments "Where Right And Glory The Royal School of Military Engineering Lead"; in Latin fas implies Corps' Ensign "sacred duty")[1] Bishop Gundulf, Rochester and King's Engineers March Wings (Quick march) The Institution of Royal Engineers Commanders The Royal Engineers' Association Current Chief Royal Engineer – Lt Sport commander Gen Tyrone Urch CBE Royal Engineers' Yacht Club Royal Engineers Amateur Football Club Corps Colonel – Col Matt FA Cup Quare MBE ADC Rugby Corps Serjeant Major - Successor units WO1 Paul Clark RE Notable personnel Chief Royal Lieutenant General Engineering equipment Engineer Tyrone Urch CBE Order of precedence Insignia Decorations Victoria Cross Tactical The Sapper VCs recognition Memorials flash See also References Further reading External links History The Royal Engineers trace their origins back to the military engineers brought to England by William the Conqueror, specifically Bishop Gundulf of Rochester Cathedral, and claim over 900 years of unbroken service to the crown. -

T I RECORD of the OLD HAILEYBURIANS WAR in SOUTH

A W SS- OWJ( t \Jxrn I (r ~ ‘ k RECORD OF THE OLD HAILEYBURIANS WHO FOUGHT IN THE ♦ WAR IN SOUTH AFRICA. i. * SUPPLEMENT TO THE 'HAILEYBURIAN No. 3 2 8 . fotw materials fax a 0f % foljn fougjjl fnr % (&m$m m % W ar m Stfirljj %txm, 1 8 9 9 — 1 0 0 2 . [I w ish to thank Mr. Turner very much for supplying me with the lists from the O.H. Society Reports, and the Editors of the Haileyburian for giving me a complete set of the numbers which I wanted. I must apologize for mistakes and omissions and inaccuracies, but I hope at any rate to shew that our “ friends abroad ” have been “ borne in mind ” by the “ friends at home they left behind/’ The Obelisk in the Avenue and the Eoll of Honour in the Cloisters will be a fitting memorial on the spot, but we are anxious to send some record away, and this must serve for want of a better. L. S. MILFORD.] t may be worth while to record the various steps in the history of the O.H. I War Memorial after the original proposal in a letter to the Haileyburian. At a Committee Meeting of the O.H. Society held on Nov. 15th, 1900, it was resolved that the O.H. Society should take up the question of a Memorial. On December 6th, 1900, a General Meeting of O.Hs. was held at the Church House, Westminster, under the Presidency of G. S. Pawle, as President of the O.H.