Unit 14 Janapadas and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Emergence of the Mahajanapadas

The Emergence of the Mahajanapadas Sanjay Sharma Introduction In the post-Vedic period, the centre of activity shifted from the upper Ganga valley or madhyadesha to middle and lower Ganga valleys known in the contemporary Buddhist texts as majjhimadesha. Painted grey ware pottery gave way to a richer and shinier northern black polished ware which signified new trends in commercial activities and rising levels of prosperity. Imprtant features of the period between c. 600 and 321 BC include, inter-alia, rise of ‘heterodox belief systems’ resulting in an intellectual revolution, expansion of trade and commerce leading to the emergence of urban life mainly in the region of Ganga valley and evolution of vast territorial states called the mahajanapadas from the smaller ones of the later Vedic period which, as we have seen, were known as the janapadas. Increased surplus production resulted in the expansion of trading activities on one hand and an increase in the amount of taxes for the ruler on the other. The latter helped in the evolution of large territorial states and increased commercial activity facilitated the growth of cities and towns along with the evolution of money economy. The ruling and the priestly elites cornered most of the agricultural surplus produced by the vaishyas and the shudras (as labourers). The varna system became more consolidated and perpetual. It was in this background that the two great belief systems, Jainism and Buddhism, emerged. They posed serious challenge to the Brahmanical socio-religious philosophy. These belief systems had a primary aim to liberate the lower classes from the fetters of orthodox Brahmanism. -

Configurations of the Indic States System

Comparative Civilizations Review Volume 34 Number 34 Spring 1996 Article 6 4-1-1996 Configurations of the Indic States System David Wilkinson University of California, Los Angeles Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr Recommended Citation Wilkinson, David (1996) "Configurations of the Indic States System," Comparative Civilizations Review: Vol. 34 : No. 34 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr/vol34/iss34/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Comparative Civilizations Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Wilkinson: Configurations of the Indic States System 63 CONFIGURATIONS OF THE INDIC STATES SYSTEM David Wilkinson In his essay "De systematibus civitatum," Martin Wight sought to clari- fy Pufendorfs concept of states-systems, and in doing so "to formulate some of the questions or propositions which a comparative study of states-systems would examine." (1977:22) "States system" is variously defined, with variation especially as to the degrees of common purpose, unity of action, and mutually recognized legitima- cy thought to be properly entailed by that concept. As cited by Wight (1977:21-23), Heeren's concept is federal, Pufendorfs confederal, Wight's own one rather of mutuality of recognized legitimate independence. Montague Bernard's minimal definition—"a group of states having relations more or less permanent with one another"—begs no questions, and is adopted in this article. Wight's essay poses a rich menu of questions for the comparative study of states systems. -

5. from Janapadas to Empire

MODULE - 1 Ancient India 5 Notes FROM JANAPADAS TO EMPIRE In the last chapter we studied how later Vedic people started agriculture in the Ganga basin and settled down in permanent villages. In this chapter, we will discuss how increased agricultural activity and settled life led to the rise of sixteen Mahajanapadas (large territorial states) in north India in sixth century BC. We will also examine the factors, which enabled Magadh one of these states to defeat all others to rise to the status of an empire later under the Mauryas. The Mauryan period was one of great economic and cultural progress. However, the Mauryan Empire collapsed within fifty years of the death of Ashoka. We will analyse the factors responsible for this decline. This period (6th century BC) is also known for the rise of many new religions like Buddhism and Jainism. We will be looking at the factors responsible for the emer- gence of these religions and also inform you about their main doctrines. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson, you will be able to explain the material and social factors (e.g. growth of agriculture and new social classes), which became the basis for the rise of Mahajanapada and the new religions in the sixth century BC; analyse the doctrine, patronage, spread and impact of Buddhism and Jainism; trace the growth of Indian polity from smaller states to empires and list the six- teen Mahajanapadas; examine the role of Ashoka in the consolidation of the empire through his policy of Dhamma; recognise the main features– administration, economy, society and art under the Mauryas and Identify the causes of the decline of the Mauryan empire. -

List of Selected Candidates for Award of Scholarship for the Year 2016-17 Under the Scheme of "ISHAN UDAY" Special Scholarship Scheme for North Eastern Region

List of selected candidates for award of scholarship for the year 2016-17 under the scheme of "ISHAN UDAY" Special Scholarship Scheme for North Eastern Region Father Mother S.No Candidate ID Name of Applicant Domicile Name Name 1 NER-ARU-ST-2016-17-181334 SUBU KAKU SUBU HABUNG SUBU CELINE Arunachal Pradesh 2 NER-ARU-ST-2016-17-195969 AAW RIAMUK TARAK RIAMUK YAPA RIAMUK Arunachal Pradesh 3 NER-ARU-ST-2016-17-219300 KANCHAN DUI TADIK DUI YARING DUI Arunachal Pradesh 4 NER-ARU-ST-2016-17-220106 TENZIN LHAMU SANGEY KHANDU PEM DREMA Arunachal Pradesh 5 NER-ARU-ST-2016-17-211595 YANGCHIN DREMA J JIMEY NIGRUP CHEMEY Arunachal Pradesh 6 NER-ARU-ST-2016-17-178197 KEDO NASI LARKI NASI YADI NASI Arunachal Pradesh 7 NER-ARU-ST-2016-17-219318 LAMPAR NASI MAGLAM NASI YALU NASI Arunachal Pradesh 8 NER-ARU-ST-2016-17-191556 KADUM PERME BARU PERME BERENG PERME Arunachal Pradesh 9 NER-ARU-ST-2016-17-178489 LEEMSO KRI LATE DRUSO KRI ADISI KRI Arunachal Pradesh BOMLUK GAMLIN 10 NER-ARU-ST-2016-17-218088 KAZIR YOMCHA PEKHA YOMCHA Arunachal Pradesh YOMCHA 11 NER-ARU-OBC-2016-17-209560 IMRAN ALI MD.HAIDAR ALI IMAMAN BEGUM Arunachal Pradesh 12 NER-ARU-ST-2016-17-176492 KIME RINIO KIME NIPA KIME OPYUNG Arunachal Pradesh 13 NER-ARU-ST-2016-17-195045 TARH AMA TARH SONAM TARH MANGCHE Arunachal Pradesh 14 NER-ARU-ST-2016-17-200412 DEGE NGURAK TADE NGURAK VIE NGURAK Arunachal Pradesh 15 NER-ARU-GEN-2016-17-182521 SANDEEP KUMAR SINGH KAUSHAL KUMAR SINGH POONAM SINGH Arunachal Pradesh 16 NER-ARU-ST-2016-17-190517 ANGA PABIN TATE PABIN YABEN PABIN Arunachal Pradesh 17 -

Sri Krishna Janmastami

All glories to Sri Guru and Sri Gauranga SRI KRISHNA JANMASTAMI Once, the demon kings troubled the world greatly and the whole world was upset. Bhumi, the Deity of this world, went to Lord Brahma to tell him about all the trouble she had to go through as a result of all the things the demoniac kings were doing. Bhumi took the form of a cow and with tears in her eyes she approached Lord Brahma, hoping for his mercy. Lord Brahma became very sad as well and he decided to go to the ocean of milk where Lord Visnu lives. He went there together with the other demigods, Lord Siva went as well. There Lord Brahma began to speak to Lord Visnu who had saved the earth once before by taking the form of a boar (Lord Varaha). All the other demigods also offered a special prayer to Lord Visnu. This prayer is called the Purusa-Sukta prayer. On different planets there are different oceans. On our planets there are oceans of salt water but on other planets there are oceans of milk, oil or nectar. When the demigods didn’t hear any answer to their prayer, Lord Brahma decided to meditate. He received a very special message from Lord Visnu. He then gave this message to all the demigods. The message was that very soon the Supreme Lord Himself, together with His energy, strength and His eternal associates would appear into this world as the son of Vasudeva in the Yadu dynasty (Royal Family). The message also said that the demigods, along with their wives would take birth immediately in this family in this world so that they could help the Lord with His mission. -

Christ King Hr. Sec. School, Kohima Class 6 Subject: Social Sciences 2Nd Term 2020 Chapter 6 the Early States: Janapadas to Mahajanapadas

CHRIST KING HR. SEC. SCHOOL, KOHIMA CLASS 6 SUBJECT: SOCIAL SCIENCES 2ND TERM 2020 CHAPTER 6 THE EARLY STATES: JANAPADAS TO MAHAJANAPADAS A. Fill in the blanks: 1. The rajan was assisted by the commander-in-chief of the army known as Senani. 2. Most Mahajanapadas had a Capital city. 3. In a republic the people elected their ruler 4. The republics were known as Gana or Sangas 5. The first known ruler of the Maghada kingdom was Bhimbisara 6. According to Buddhist records, the people of Vijji were called Ashtakulika B. True or False 1. Magadha was the weakest of all the janapadas. False 2. The rajan was the chief of the tribe. True 3. The word ‘janapada’ means the land where the jains set their feet and settled down. False 4. Sanghas were special features for both Buddhists and Jains. True 5. Vajji was ruled by a confederacy of eight clans. True 6. Ajatashatru built the city of Pataliputra. True C. Answer in one or two sentences: 1. Who was the most famous ruler of the Nanda dynasty? Mahapadama Nanda was the most famous rulers of the Nanda dynasty. 2. Who was the first known ruler of the Magadha kingdom? The first known ruler of Magadha kingdom was Bimbisara (558-493 BC) 3. Of the sixteen mahajanapadas, which was the most powerful among them? Among the sixteenth Mahajannapadas the Magadha emerged the most powerful of all. 4. What was the main duty of the rajans? The main duty of the Rajan was to protect the kingdom by building huge forts and maintain big armies. -

Component-I (A) – Personal Details

Component-I (A) – Personal details: Component-I (B) – Description of module: Subject Name Indian Culture Paper Name Outlines of Indian History Module Name/Title Mahajanapadas- Rise of Magadha – Nandas – Invasion of Alexander Module Id I C/ OIH/ 08 Pre requisites Early History of India Objectives To study the Political institutions of Ancient India from earliest to 3rd Century BCE. Mahajanapadas , Rise of Magadha under the Haryanka, Sisunaga Dynasties, Nanda Dynasty, Persian Invasions, Alexander’s Invasion of India and its Effects Keywords Janapadas, Magadha, Haryanka, Sisunaga, Nanda, Alexander E-text (Quadrant-I) 1. Sources Political and cultural history of the period from C 600 to 300 BCE is known for the first time by a possibility of comparing evidence from different kinds of literary sources. Buddhist and Jaina texts form an authentic source of the political history of ancient India. The first four books of Sutta pitaka -- the Digha, Majjhima, Samyutta and Anguttara nikayas -- and the entire Vinaya pitaka were composed between the 5th and 3rd centuries BCE. The Sutta nipata also belongs to this period. The Jaina texts Bhagavati sutra and Parisisthaparvan represent the tradition that can be used as historical source material for this period. The Puranas also provide useful information on dynastic history. A comparison of Buddhist, Puranic and Jaina texts on the details of dynastic history reveals more disagreement. This may be due to the fact that they were compiled at different times. Apart from indigenous literary sources, there are number of Greek and Latin narratives of Alexander’s military achievements. They describe the political situation prevailing in northwest on the eve of Alexander’s invasion. -

The Mahabharata

VivekaVani - Voice of Vivekananda THE MAHABHARATA (Delivered by Swami Vivekananda at the Shakespeare Club, Pasadena, California, February 1, 1900) The other epic about which I am going to speak to you this evening, is called the Mahâbhârata. It contains the story of a race descended from King Bharata, who was the son of Dushyanta and Shakuntalâ. Mahâ means great, and Bhârata means the descendants of Bharata, from whom India has derived its name, Bhârata. Mahabharata means Great India, or the story of the great descendants of Bharata. The scene of this epic is the ancient kingdom of the Kurus, and the story is based on the great war which took place between the Kurus and the Panchâlas. So the region of the quarrel is not very big. This epic is the most popular one in India; and it exercises the same authority in India as Homer's poems did over the Greeks. As ages went on, more and more matter was added to it, until it has become a huge book of about a hundred thousand couplets. All sorts of tales, legends and myths, philosophical treatises, scraps of history, and various discussions have been added to it from time to time, until it is a vast, gigantic mass of literature; and through it all runs the old, original story. The central story of the Mahabharata is of a war between two families of cousins, one family, called the Kauravas, the other the Pândavas — for the empire of India. The Aryans came into India in small companies. Gradually, these tribes began to extend, until, at last, they became the undisputed rulers of India. -

HISTORY ANCIENT INDIA Thought of the Day

Todays Topic HISTORY ANCIENT INDIA Thought of the Day Everything is Fair in Love & War Todays Topic 16 Mahajanpadas Part – 2 16 MAHAJANPADAS Mahajanapadas with some Vital Informations – 1) Kashi - Capital - Varanasi Location - Varanasi dist of Uttar Pradesh Information - It was one of the most powerful Mahajanapadas. Famous for Cotton Textiles and market for horses. 16 MAHAJANPADAS 2) Koshala / Ayodhya - Capital – Shravasti Location - Faizabad, Gonda region or Eastern UP Information - Most popular king was Prasenjit. He was contemporary and friend of Buddha . 16 MAHAJANPADAS 3) Anga - Capital – Champa / Champanagari Location - Munger and Bhagalpur Dist of Bihar Information - It was a great centre of trade and commerce . In middle of 6th century BC, Anga was annexed by Magadha under Bimbisara. 16 MAHAJANPADAS 4) Vajji ( North Bihar ) - Capital – Vaishali Location – Vaishali dist. of Bihar Information - Vajjis represented a confederacy of eight clans of whom Videhas were the most well known. আটট বংেশর একট সংেঘর িতিনিধ কেরিছেলন, যােদর মেধ িভডাহস সবািধক পিরিচত। • Videhas had their capital at Mithila. 16 MAHAJANPADAS 5) Malla ( Gorakhpur Region ) - Capital – Pavapuri in Kushinagar Location – South of Vaishali dist in UP Information - Buddha died in the vicinity of Kushinagar. Magadha annexed it after Buddha's death. 16 MAHAJANPADAS 6) Chedi - Capital – Suktimati Location – Eastern part of Bundelkhand Information - Chedi territory Corresponds to the Eastern parts of modern Bundelkhand . A branch of Chedis founded a royal dynasty in the kingdom of Kalinga . 16 MAHAJANPADAS 16 MAHAJANPADAS 7) Vatsa - Capital – Kausambi Location – Dist of Allahabad, Mirzapur of Uttar Pradesh Information - Situated around the region of Allahabad. -

Rajaji-Mahabharata.Pdf

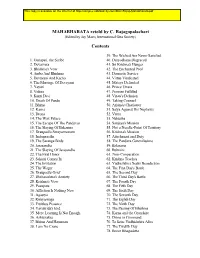

MAHABHARATA retold by C. Rajagopalachari (Edited by Jay Mazo, International Gita Society) Contents 39. The Wicked Are Never Satisfied 1. Ganapati, the Scribe 40. Duryodhana Disgraced 2. Devavrata 41. Sri Krishna's Hunger 3. Bhishma's Vow 42. The Enchanted Pool 4. Amba And Bhishma 43. Domestic Service 5. Devayani And Kacha 44. Virtue Vindicated 6. The Marriage Of Devayani 45. Matsya Defended 7. Yayati 46. Prince Uttara 8. Vidura 47. Promise Fulfilled 9. Kunti Devi 48. Virata's Delusion 10. Death Of Pandu 49. Taking Counsel 11. Bhima 50. Arjuna's Charioteer 12. Karna 51. Salya Against His Nephews 13. Drona 52. Vritra 14. The Wax Palace 53. Nahusha 15. The Escape Of The Pandavas 54. Sanjaya's Mission 16. The Slaying Of Bakasura 55. Not a Needle-Point Of Territory 17. Draupadi's Swayamvaram 56. Krishna's Mission 18. Indraprastha 57. Attachment and Duty 19. The Saranga Birds 58. The Pandava Generalissimo 20. Jarasandha 59. Balarama 21. The Slaying Of Jarasandha 60. Rukmini 22. The First Honor 61. Non-Cooperation 23. Sakuni Comes In 62. Krishna Teaches 24. The Invitation 63. Yudhishthira Seeks Benediction 25. The Wager 64. The First Day's Battle 26. Draupadi's Grief 65. The Second Day 27. Dhritarashtra's Anxiety 66. The Third Day's Battle 28. Krishna's Vow 67. The Fourth Day 29. Pasupata 68. The Fifth Day 30. Affliction Is Nothing New 69. The Sixth Day 31. Agastya 70. The Seventh Day 32. Rishyasringa 71. The Eighth Day 33. Fruitless Penance 72. The Ninth Day 34. Yavakrida's End 73. -

Socio- Political and Administrative History of Ancient India (Early Time to 8Th-12Th Century C.E)

DDCE/History (M.A)/SLM/Paper-XII Socio- Political and Administrative History of Ancient India (Early time to 8th-12th Century C.E) By Dr. Binod Bihari Satpathy 0 CONTENT SOCIO- POLITICAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE HISTORY OF ANCIENT INDIA (EARLY TIME TO 8th-12th CENTURIES C.E) Unit.No. Chapter Name Page No Unit-I. Political Condition. 1. The emergence of Rajput: Pratiharas, Art and Architecture. 02-14 2. The Rashtrakutas of Manyakheta: Their role in history, 15-27 Contribution to art and culture. 3. The Pala of Bengal- Polity, Economy and Social conditions. 28-47 Unit-II Other political dynasties of early medieval India. 1. The Somavamsis of Odisha. 48-64 2. Cholas Empire: Local Self Government, Art and Architecture. 65-82 3. Features of Indian Village System, Society, Economy, Art and 83-99 learning in South India. Unit-III. Indian Society in early Medieval Age. 1. Social stratification: Proliferation of castes, Status of women, 100-112 Matrilineal System, Aryanisation of hinterland region. 2. Religion-Bhakti Movements, Saivism, Vaishnavism, Tantricism, 113-128 Islam. 3. Development of Art and Architecture: Evolution of Temple Architecture- Major regional Schools, Sculpture, Bronzes and 129-145 Paintings. Unit-IV. Indian Economy in early medieval age. 1. General review of the economic life: Agrarian and Urban 146-161 Economy. 2. Indian Feudalism: Characteristic, Nature and features. 162-180 Significance. 3. Trade and commerce- Maritime Activities, Spread of Indian 181-199 Culture abroad, Cultural Interaction. 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT It is pleasure to be able to complete this compilation work. containing various aspects of Ancient Indian History. This material is prepared with an objective to familiarize the students of M.A History, DDCE Utkal University on the various aspcets of India’s ancient past. -

The Panchala Maha Utsav a Tribute to the Rich Cultural Heritage of Auspicious Panchala Desha and It’S Brave Princess Draupadi

Commemorting 10years with The Panchala Maha Utsav A Tribute to the rich Cultural Heritage of auspicious Panchala Desha and It’s brave Princess Draupadi. The First of its kind Historic Celebration We Enter The Past, To Create Opportunities For The Future A Report of Proceedings Of programs from 15th -19th Dec 2013 At Dilli Haat and India International Center 2 1 Objective Panchala region is a rich repository of tangible & intangible heritage & culture and has a legacy of rich history and literature, Kampilya being a great centre for Vedic leanings. Tangible heritage is being preserved by Archaeological Survey of India (Kampilya , Ahichchetra, Sankia etc being Nationally Protected Sites). However, negligible or very little attention has been given to the intangible arts & traditions related to the Panchala history. Intangible heritage is a part of the living traditions and form a very important component of our collective cultures and traditions, as well as History. As Draupadi Trust completed 10 years on 15th Dec 2013, we celebrated our progressive woman Draupadi, and the A Master Piece titled Parvati excavated at Panchala Desha (Ahichhetra Region) during the 1940 excavation and now a prestigious display at National Museum, Rich Cultural Heritage of her historic New Delhi. Panchala Desha. We organised the “Panchaala Maha Utsav” with special Unique Features: (a) Half Moon indicating ‘Chandravanshi’ focus on the Vedic city i.e. Draupadi’s lineage from King Drupad, (b) Third Eye of Shiva, (c) Exquisite Kampilya. The main highlights of this Hairstyle (showing Draupadi’s love for her hair). MahaUtsav was the showcasing of the Culture, Crafts and other Tangible and Intangible Heritage of this rich land, which is on the banks of Ganga, this reverend land of Draupadi’s birth, land of Sage Kapil Muni, of Ayurvedic Gospel Charac Saminhita, of Buddha & Jain Tirthankaras, the land visited by Hiuen Tsang & Alexander Cunningham, and much more.