Dasen 2019 Arc 06 Dos Jeux Lr.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History Bible Literature G 4-Day Sample.Pdf

HISTORY / BIBLE / LITERATURE INSTRUCTOR’S GUIDE WORLD HISTORY Year 1 of 2 The Colosseum G Rome, Italy FUN FACT Hatshepsut was the f rst female pharaoh. 4-DAY G Ages 12–14 Grades 7–9 History Bible Literature (4-Day) World History, Year 1 of 2 By the Sonlight Team Train up a child in the way he should go, And when he is old he will not depart from it Proverbs 22:6 (NKJV) INSTRUCTOR’S GUIDE Thank you for downloading this sample of Sonlight’s History / Bible / Literature G Instructor’s Guide (what we affectionately refer to as an IG). In order to give you a full perspective on our Instructor’s Guides, this sample will include parts from every section that is included in the full IG. Here’s a quick overview of what you’ll find in this sample. Ҍ A Quick Start Guide Ҍ A 3-week Schedule Ҍ Discussion questions, notes and additional features to enhance your school year Ҍ A Scope and Sequence of topics and and skills your children will be developing throughout the school year Ҍ A schedule for Timeline Figures Ҍ Samples of the full-color laminated maps included in History / Bible / Literature IGs to help your children locate key places mentioned in your history, Reader and Read-Aloud books SONLIGHT’S “SECRET” COMES DOWN TO THIS: We believe most children respond more positively to great literature than they do to textbooks. To properly use this sample to teach your student, you will need the books that are scheduled in it. -

Introduction

Introduction When we study history from its beginning, one of the first civilizations we find is Ancient Egypt. While there are many other ancient peoples, Egypt is always listed as one of the most important. It endured longer than any of its neighbors, and in so doing, it estab- lished itself as a foundation that the story of ancient history could be built on. For century after century, the Egyptians built stone monuments and pyramids, carved countless pictures and hieroglyphs, recorded stories and important information on papyrus scrolls, and in the process preserved for future generations pieces of a story that would otherwise barely be remembered. The stability of their geographic location — surrounded by deserts but living along the fertile Nile River — allowed them to maintain their culture comparatively undisturbed for long periods of time. Here they farmed, built, and raised their families. They also, importantly, figured prominently in several stories from the Bible, making them an integral part of God’s divine plan as it was laid out in the Old Testament. For these reasons and many others, they are one of the most important civilizations we can take time to study. Each lesson in this Project Passport includes fact-filled, engaging text, created to be all you need for a compact assignment. Should you or your child wish to expound on a subject, a variety of books, videos, and further avenues of research are available in the “Additional Resources” section. This study can also act as an excellent accompaniment to any world history program. You will want to print out the “Travel Tips” teacher helps beforehand and brief yourself on the lessons and supplies needed. -

Whose Game Is It Anyway? Board and Dice Games As an Example of Cultural Transfer and Hybridity Mark Hall

Whose Game is it Anyway? Board and Dice Games as an Example of Cultural Transfer and Hybridity Mark Hall To cite this version: Mark Hall. Whose Game is it Anyway? Board and Dice Games as an Example of Cultural Transfer and Hybridity. Archimède : archéologie et histoire ancienne, UMR7044 - Archimède, 2019, pp.199-212. halshs-02927544 HAL Id: halshs-02927544 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02927544 Submitted on 1 Sep 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. ARCHIMÈDE N°6 ARCHÉOLOGIE ET HISTOIRE ANCIENNE 2019 1 DOSSIER THÉMATIQUE : HISTOIRES DE FIGURES CONSTRUITES : LES FONDATEURS DE RELIGION DOSSIER THÉMATIQUE : JOUER DANS L’ANTIQUITÉ : IDENTITÉ ET MULTICULTURALITÉ GAMES AND PLAY IN ANTIQUITY: IDENTITY AND MULTICULTURALITY 71 Véronique DASEN et Ulrich SCHÄDLER Introduction EGYPTE 75 Anne DUNN-VATURI Aux sources du « jeu du chien et du chacal » 89 Alex DE VOOGT Traces of Appropriation: Roman Board Games in Egypt and Sudan 100 Thierry DEPAULIS Dés coptes ? Dés indiens ? MONDE GREC 113 Richard. H.J. ASHTON Astragaloi on Greek Coins of Asia Minor 127 Véronique DASEN Saltimbanques et circulation de jeux 144 Despina IGNATIADOU Luxury Board Games for the Northern Greek Elite 160 Ulrich SCHÄDLER Greeks, Etruscans, and Celts at play MONDE ROMAIN 175 Rudolf HAENSCH Spiele und Spielen im römischen Ägypten: Die Zeugnisse der verschiedenen Quellenarten 186 Yves MANNIEZ Jouer dans l’au-delà ? Le mobilier ludique des sépultures de Gaule méridionale et de Corse (Ve siècle av. -

Geo Sampler November 2019 Game On

THE GEO-SAMPLER NOVEMBER 2019 In the midst of the festive holiday season, we here in the lab start thinking about being bored. Not here, of course, but with our families, during all that, uh, family time. Which “People say nothing is makes us think about board games, a fun way to connect the generations with the cut- impossible but I can do throat competitive spirit that fuels decades of family traditions and heartaches. So, this nothing every day.” got us to thinking: Monopoly or Parcheesi? And also: without rolling the dice, how did board games get started? GAMEThough thousands and thousands of dif- discovered ON! a group of non-Puritans play- ferent board games have existed over the ing in the streets on Christmas Day in 1622, millennia, there are some things all share he literally ‘took the ball and went home,’ It’s in common; they’re typically played on a reprimanding the townspeople that their technical tabletop, they motivate players to achieve joy for the day should be confined to their a goal, and they have that which drives home. (And perhaps setting up what would “The factory of the future wedges between sib- become a long tradi- will have only two employees, lings: rules. tion of Clue on Christ- a man, and a dog. The man mas Day throughout will be there to feed the Board games are an- dog. The dog will be there to the land.) cient history, we’ve keep the man from touching learned thanks to The board game Trav- the equipment.” myriad archeologi- eller’s Tour Through “If computers get too cal sites. -

Core G—Map 1

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 A GREENLAND Scandinavia ICELAND CANADA Newfoundland (Vineland) IRELAND ASIA B St. John’s Calais MONGOLIA NORTH Gulf of St. Lawrence AMERICA Fertile Crescent Silk Road KOREA JAPAN Kyoto C MEXICO Islamic Empire Sahara Desert West Indies INDIA CHAD BARBADOS Koumbi SalehAFRICA Mariana Islands G— Core Mesoamerica Caribbean Sea Indian Ocean PHILIPPINES D Central Atlantic Ocean Pacic Ocean ©2014 by Sonlight Curriculum, Ltd. All rights reserved. All Ltd. Sonlight Curriculum, ©2014 by America Guiana Bismarck Archipelago INDONESIA New PERU SOUTH Map 1 E Guinea AMERICA Easter Island Andes Mountains Great Zimbabwe ZIMBABWE AUSTRALIA F Cape of Good Hope Map Legend NEW ZEALAND G Cities Straits of Magellan States/Provinces Antipodes Islands COUNTRIES Cape Horn Regions H CONTINENTS Bodies of Water Deserts Mountain Mountain Range I Points of Interest 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 A SWEDEN NORWAY Baltic rights reserved. All Ltd. Sonlight Curriculum, ©2014 by B SCOTLAND Sea IRELAND Virconium BRITAIN Antwerp Agincourt UKRAINE AUSTRIA C FRANCE Danube River Poitou Savoy Venice Ravenna Balkans Black Sea PORTUGAL SPAIN Great Wall of China NORTH KOREA GREECE TURKEY Beijing Kaesong Yellow River Panmunjom G— Core CHINA Seoul Rock of Gibraltar Akkad D Tangier Kum River RUSSIA Xianyang MOROCCO Salt Sea Samaria PERSIA IRAN Nanjing Nile Delta ARABIA Tibet Ch’ang-an Kangjin Persepolis Judea Indus Valley Delhi Lower Egypt Ganges River Yangtze River Mohenjo-Daro Agra Map 2 Assyrian Empire Abydos Persian E Nile River Gulf Taghaza EGYPT Taiwan Mecca -

WORLD HISTORY Year 1 of 2

HISTORY / BIBLE / LITERATURE INSTRUCTOR’S GUIDE WORLD HISTORY Year 1 of 2 The Colosseum G Rome, Italy FUN FACT Hatshepsut was the first female pharaoh. Thank you for downloading this sample of Sonlight’s History / Bible / Literature G Instructor’s Guide (what we affectionately refer to as an IG). In order to give you a full perspective on our Instructor’s Guides, this sample will include parts from every section that is included in the full IG. Here’s a quick overview of what you’ll find in this sample. Ҍ A Quick Start Guide Ҍ A 3-week Schedule Ҍ Discussion questions, notes and additional features to enhance your school year Ҍ A Scope and Sequence of topics and and skills your children will be developing throughout the school year Ҍ A schedule for Timeline Figures Ҍ Samples of the full-color laminated maps included in History / Bible / Literature IGs to help your children locate key places mentioned in your history, Reader and Read-Aloud books SONLIGHT’S “SECRET” COMES DOWN TO THIS: We believe most children respond more positively to great literature than they do to textbooks. To properly use this sample to teach your student, you will need the books that are scheduled in it. We include all the books you will need when you purchase a package from sonlight.com. Curriculum experts develop each IG to ensure that you have everything you need for your homeschool day. Every IG offers a customizable homeschool schedule, complete lesson plans, pertinent activities, and thoughtful questions to aid your students’ comprehension. -

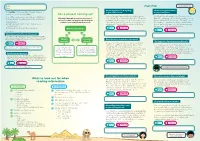

What to Look out for When Reading Information Fact File Got a Project

Name: Fact File Find a balanced view. Class: Ancient Egyptians ate hedgehogs The Ancient Egyptians liked The Fact File provides you with information that may or as part of their meals. to play board games. may not be true about Ancient Egypt. Got a project coming up? I went to the public library and borrowed a book about I read from National Geographic Kids -Everything Ancient Some of them are based on mere opinions. Your first task is Ancient Egypt. The book mentioned that Ancient Egyptians Egypt that the Egyptians liked to play board games such as to discern whether the claims made are true or otherwise. Visit http://www.nlb.gov.sg/sure/six-steps-to- success-2/ to find out what are the six steps to ate hippos, gazelles, cranes as well as smaller animals such Hounds and Jackals, Mehen and Senet. Though the rules for 1. Read carefully. conduct a successful information search. as hedgehogs for meals. I believe this to be true since the these games are long forgotten, there are modern games 2. Tick the circle with “Fact” or “Opinion” based on your information is from a book that is available at the library. that are similar to the games Ancient Egyptians play now careful evaluation. like Snakes and Ladders and Backgammon. 3. Write down your reasons in the box provided. Well-researched topic FACT OPINION FACT OPINION Some examples... Tutankhamun became Pharaoh at the age of 9. I read it in a book called Everything Ancient Egypt by National Geographic that Tutankhamun became Pharoah in 1333 BCE when he was 9 years old. -

2016 ASOR Program Book.Pdf

November 16–19 | San Antonio, Texas Welcome to ASOR’s 2016 Annual Meeting 2–5 History and Mission of ASOR 6–7 Meeting Highlights 7 Program-at-a-Glance 10–12 Schedule of Business Meetings, Receptions, and Events 13–15 Academic Program 18–45 Projects on Parade Poster Session 46–47 Contents Hotel and General Information 49 Members’ Meeting Agenda 50 of ASOR’s Legacy Circle 50 2016 Sponsors and Exhibitors 51–56 Ten Things To Do in San Antonio 58 Looking ahead to the 2017 Annual Meeting 59 Table Table Fiscal Year 2016 Honor Roll 60–61 Annual Fund Pledge Card 62 Excavation Grants and Fellowships Awarded 63 2015 Honors and Awards 65 ACOR Jordanian Travel Scholarships 66 2017 Annual Meeting Registration Form 67 2017 ASOR Membership Form 68 ASOR Journals 69 Institutional Members 72 ASOR Staff 73 ASOR Board of Trustees 74 ASOR Committees 75–77 Overseas Centers 78 Paper Abstracts 80–182 Poster Abstracts 182–190 Index of Sessions 191–193 Index of Presenters 194–198 Notes and Contacts 199–204 La Cantera Resort and Spa, Floor Plan 206–207 ISBN 978-0-89757-096-1 ASOR PROGRAM GUIDE 2016 | 1 American Schools of Oriental Research | 2016 Annual Meeting Welcome from ASOR President, Susan Ackerman Welcome to ASOR’s 2016 Annual Meeting! The Program Committee has once more done an incredible job, putting together a rich and vibrant program of sessions and posters, covering all the major regions of the Near East and wider Mediterranean from earliest times through the Islamic period. I am especially pleased that some of our newer sessions—for example, on the archaeology of the Kurdistan region of Iraq and on the archaeology of monasticism—continue to thrive, and I am also pleased that our program demonstrates more and more ASOR’s expanded geographical and cultural reach. -

Games, Gods and Gambling : the Origins and History of Probability and Statistical Ideas from the Earliest Times to the Newtonian Era

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Alberta Gambling Research Institute Alberta Gambling Research Institute 1962 Games, gods and gambling : the origins and history of probability and statistical ideas from the earliest times to the Newtonian era David, F. N. (Florence Nightingale) Hafner Publishing Company http://hdl.handle.net/1880/41346 book Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca Games, Gods and Gambling rc same author: 1 STATISTICAL PRIMER D. E. BARTON, B.Sc., Ph.D.: 2OMBINATORIAL CHANCE Signs of the Zodiac : floor mosaic, Beth-Aleph Synagogue, Palestine (5th century) Games, Gods and Gambling The origins and history of probability and statistical ideas from the earliest times to the Newtonian era F. N. DAVID, D.Sc. (University of London, University College) 1962 HAFNER PUBLISHING COMPANY NEW YORK Copyright 0 1962 CHARLES GRIFFIN & CO. LTD 42 DRURY LANE LONDON W.C.2 First Published in 1962 PRINTED IN GREAT BRpTAIN BY BELL AND BAIN, LTD., GLASOOW [S CONTINUING INTEREST AND ENCOURAGEMENT all we tell you? Tales, marvellous tales and stars and isles where good men rest, evermore the rose of sunset pales, ds and shadows fall toward the West. v beguile you? Death hath no repose and deeper than that Orient sand [ides the beauty and bright faith of those rde the Golden Journey to Samarkand. v they wait and whiten peaceably, mquerors, those poets, those so fair ; ow time comes, not only you and I, whole world shall whiten, here or there : lose long caravans that cross the plain untless feet and sound of silver bells 1 no more for glory or for gain, 8 more solace from the palm-girt wells ; le great markets by the sea shut fast calm Sunday that goes on and on, ven lovers find their peace at last, rth is but a star, that once had shone. -

Paper Abstracts

PAPER ABSTRACTS Plenary Address Eric H. Cline (The George Washington University), “Dirt, Digging, Dreams, and Drama: Why Presenting Proper Archaeology to the Public is Crucial for the Future of Our Field” We seem to have forgotten that previous generations of Near Eastern archaeologists knew full well the need to bring their work before the eyes of the general public; think especially of V. Gordon Childe, Sir Leonard Woolley, Gertrude Bell, James Henry Breasted, Yigael Yadin, Dame Kathleen Kenyon, and a whole host of others who lectured widely and wrote prolifically. Breasted even created a movie on the exploits of the Oriental Institute, which debuted at Carnegie Hall and then played around the country in the 1930s. The public was hungry for accurate information back then and is still hungry for it today. And yet, with a few exceptions, we have lost sight of this, sacrificed to the goal of achieving tenure and other perceived institutional norms, and have left it to others to tell our stories for us, not always to our satisfaction. I believe that it is time for us all— not just a few, but as many as possible—to once again begin telling our own stories about our findings and presenting our archaeological work in ways that make it relevant, interesting, and engaging to a broader audience. We need to deliver our findings and our thoughts about the ancient world in a way that will not only attract but excite our audiences. Our livelihoods, and the future of the field, depend upon it, for this is true not only for our lectures and writings for the general public but also in our classrooms. -

Ancient Board Games in Perspective | Iii 15 Horse Coins: Pieces for Da Ma, the Chinese Board-Game 'Driving the Horses' 116 Joe Crihb

Preface Notes on the Contributors Board Games in Perspective: An Introduction 1 Irving L. Finkel 1 Homo Ludens: The Earliest Board Games in the Near East 5 Stjohn Simpson 2 The Royal Game of Ur 11 Andrea Becker 3 On the Rules for the Royal Game of Ur 16 Irving L Finkel 4 Mehen: The Ancient Egyptian Game of the Serpent 33 Timothy Kendall 5 Were There Gamesters in Pharaonic Egypt? 46 W.J.Tait 6 The Egyptian Game of Senet and the Migration of the Soul 54 Peter A. Piccione 7 The Game of Hounds and Jackals 64 A.J.Hoerth 8 The Egyptian 'Game of Twenty Squares': Is It Related to 'Marbles' and the Game of the Snake? 69 Edgar B. Pusch 9 Board Games and their Symbols from Roman Times to Early Christianity 87 Anita Rieche 10 Inscribed Imperial Roman Gaming-Boards 90 Nicholas Purcell 11 Notes on Pavement Games of Greece and Rome 98 R. C. Bell 12 Late Roman and Byzantine Game Boards at Aphrodisias 100 Charlotte Roueche 13 Graeco-Roman Pavement Signs and Game Boards: A British Museum Working Typology 106 R. C. Belt and C. M. Roueche 14 Game Boards at Vijayanagara: A Preliminary Report 110 John M. Fritz and David Cibson Ancient Board Games in Perspective | iii 15 Horse Coins: Pieces for Da Ma, the Chinese Board-Game 'Driving the Horses' 116 Joe Crihb 16 An Introduction to Board Games in Late Imperial China 125 Andrew Lo 17 Co in China 133 John Fairbaim 18 The Beginnings of Chess 138 Michael Mark 19 Grandmasters of Shatranj and the Dating of Chess 158 R. -

Reflective Learning Journal

Social ritual and religion in ancient Egyptian board games. Author: Phillip Robinson Date: May, 2015 URL: http://www.museumofgaming.org.uk/papers/ritual_in_egyptian_board_games.pdf Abstract: Board games are particularly well represented in the archaeological record of ancient Egypt. Their connections with ancient Egyptian religion means there are also references to gaming in religious texts and funerary artwork. Games by their very nature have a social element to them, they usually require more than one player and are often played with friends or family. When religion and ritual is attached to such games they can take on magical properties. In ancient Egypt this could be your ticket to the underworld or even a system which allowed communication with the dead. Social ritual and religion in ancient Egyptian board games. It is a part of human nature to play and toys and games can be used as a method for transferring essential skills; they can provide a way to practice real life events in a safe and controlled environment. Games that involve throwing, running, hiding and discovery all use skills that were useful for our ancestors to hone their techniques for hunting and fighting. As society developed so did early formal gaming; games appeared with dedicated playing pieces, set rules and organised play. There is evidence of board games being played in the ancient Near East over 9,000 years ago with game boards found in Pre-Pottery Neolithic B contexts such as those at Beidha (Kirkbride, 1966). Games soon developed into a method for encouraging and practising strategic thinking and moving opposing pieces on a reference grid became a popular game mechanic.