King Alfred, Mercia and London, 874-886: a Reassessment by Jeremy Haslam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comparative Analysis of the Process of Initial State Genesis in Rus' and Bulgaria

Comparative Analysis of the Process of Initial State Genesis in Rus' and Bulgaria Evgeniy A. Shinakov Svetlana G. Polyakova Bryansk State University ABSTRACT There has not been completed yet the typological research of Euro- pean polities' forms (of the complexity level of ‘barbarous’ state- hood, ‘complex chiefdoms’, and rarely – ‘early states’ – in terms of political anthropology), and of the pathways of their emergence. This research can be amplified with the study of the First Bulgar- ian kingdom before Omurtag's and Krum's reforms (the end of the 7th – the early 9th century) and synchronous to it complex chief- dom of ‘Rosia’ (in terms of Porphyrpgenitus) of the end of the 9th – mid-10th century. They have typological similarity in military and contractual character of pathways of state genesis (in ‘Rosia’ it is supplemented by foreign trade) as well as in the form of ‘barba- rous’ (pre-Christian) statehood. It has a multilevel – ‘federal’ – character. At the head there were the Turks-Bulgarians and the ‘Rhos’ (‘Ruses’), whose settlements had limited territory, the ‘slavini- yas’ with their own power structure were subordinated to them and supervised by the ‘federal’ power strong points. The ‘supreme’ power domination is supported not only by the fear of weapon, but also by the treaties based on reciprocity. The common interest was, for exam- ple, the participation in robbery of the Byzantine Empire and interna- tional trade. At first in a peaceful way, later with conflicts, Bulgaria was transformed into a unitarian territorial state by the reforms of the pagans Оmurtag and Krum, and then of the Christian Boris (the latter had led to the conflict within the top level of power – among the Turkic-Bulgarians aristocracy). -

Byzantine Missionaries, Foreign Rulers, and Christian Narratives (Ca

Conversion and Empire: Byzantine Missionaries, Foreign Rulers, and Christian Narratives (ca. 300-900) by Alexander Borislavov Angelov A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor John V.A. Fine, Jr., Chair Professor Emeritus H. Don Cameron Professor Paul Christopher Johnson Professor Raymond H. Van Dam Associate Professor Diane Owen Hughes © Alexander Borislavov Angelov 2011 To my mother Irina with all my love and gratitude ii Acknowledgements To put in words deepest feelings of gratitude to so many people and for so many things is to reflect on various encounters and influences. In a sense, it is to sketch out a singular narrative but of many personal “conversions.” So now, being here, I am looking back, and it all seems so clear and obvious. But, it is the historian in me that realizes best the numerous situations, emotions, and dilemmas that brought me where I am. I feel so profoundly thankful for a journey that even I, obsessed with planning, could not have fully anticipated. In a final analysis, as my dissertation grew so did I, but neither could have become better without the presence of the people or the institutions that I feel so fortunate to be able to acknowledge here. At the University of Michigan, I first thank my mentor John Fine for his tremendous academic support over the years, for his friendship always present when most needed, and for best illustrating to me how true knowledge does in fact produce better humanity. -

Wessex and the Reign of Edmund Ii Ironside

Chapter 16 Wessex and the Reign of Edmund ii Ironside David McDermott Edmund Ironside, the eldest surviving son of Æthelred ii (‘the Unready’), is an often overlooked political figure. This results primarily from the brevity of his reign, which lasted approximately seven months, from 23 April to 30 November 1016. It could also be said that Edmund’s legacy compares unfavourably with those of his forebears. Unlike other Anglo-Saxon Kings of England whose lon- ger reigns and periods of uninterrupted peace gave them opportunities to leg- islate, renovate the currency or reform the Church, Edmund’s brief rule was dominated by the need to quell initial domestic opposition to his rule, and prevent a determined foreign adversary seizing the throne. Edmund conduct- ed his kingship under demanding circumstances and for his resolute, indefati- gable and mostly successful resistance to Cnut, his career deserves to be dis- cussed and his successes acknowledged. Before discussing the importance of Wessex for Edmund Ironside, it is con- structive, at this stage, to clarify what is meant by ‘Wessex’. It is also fitting to use the definition of the region provided by Barbara Yorke. The core shires of Wessex may be reliably regarded as Devon, Somerset, Dorset, Wiltshire, Berk- shire and Hampshire (including the Isle of Wight).1 Following the victory of the West Saxon King Ecgbert at the battle of Ellendun (Wroughton, Wilts.) in 835, the borders of Wessex expanded, with the counties of Kent, Sussex, Surrey and Essex passing from Mercian to West Saxon control.2 Wessex was not the only region with which Edmund was associated, and nor was he the only king from the royal House of Wessex with connections to other regions. -

Introduction

Cambridge University Press 0521819458 - Kingship and Politics in the Late Ninth Century: Charles the Fat and the End of the Carolingian Empire Simon Maclean Excerpt More information Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION the end of the carolingian empire in modern historiography The dregs of the Carlovingian race no longer exhibited any symptoms of virtue or power, and the ridiculous epithets of the Bald, the Stammerer, the Fat, and the Simple, distinguished the tame and uniform features of a crowd of kings alike deserving of oblivion. By the failure of the collateral branches, the whole inheritance devolved to Charles the Fat, the last emperor of his family: his insanity authorised the desertion of Germany, Italy, and France...Thegovernors,the bishops and the lords usurped the fragments of the falling empire.1 This was how, in the late eighteenth century, the great Enlightenment historianEdward Gibbonpassed verdict onthe endof the Carolingian empire almost exactly 900 years earlier. To twenty-first-century eyes, the terms of this assessment may seem jarring. Gibbon’s emphasis on the im- portance of virtue and his ideas about who or what was a deserving subject of historical study very much reflect the values of his age, the expectations of his audience and the intentions of his work.2 However, if the timbre of his analysis now feels dated, its constituent elements have nonetheless survived into modern historiography. The conventional narrative of the end of the empire in the year 888 is still a story about the emergence of recognisable medieval kingdoms which would become modern nations – France, Germany and Italy; about the personal inadequacies of late ninth- century kings as rulers; and about their powerlessness in the face of an increasingly independent, acquisitive and assertive aristocracy. -

The Environmental History of Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site

CENTER FOR PUBLIC HISTORY AND ARCHAEOLOGY COLORADO STATE UNIVERSITY The Environmental History of Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site Final Draft Elizabeth Michell July 31 2009 An abbreviated version intended as guide for visitors OYL/iJ INTRODUCTION On late spring day visitor stands on slight rise on the banks of Big Sandy Creek from where across Cheyenne chief Black Kettles village once stood whole lot of he nothing comments laconically It is quiet place its peacefulness giving it timeless But quality the visitor is wrong and the timelessness is deceptive You can never visit the past again The Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site is in southeastern fifteen Colorado about miles northeast of the small town of Eads This is high plains country dusty and flat the drab greens of grass and scrub melding into the relentless browns of desiccated vegetation sand and soil The surrounding landscape is crisscrossed dirt by trails and fence lines dotted with windmills outbuildings and stock watering tanks At the site groves of cottonwoods tower along the gently sloping banks of Big Sandy Creek in fact it would be difficult to follow the stream course without the line of trees For most of the year water does not flow and the creek bed is choked with sand sagebrushes and other the site dry prairie species Though is part of shortgrass most of the land is prairie actually sandy bottomland that may eventually become It in Black Kettles tallgrass prairie was dry time and it is still dry evident by how much more sagebrush species there are now -

Marking Systems

by Underhill® Marking Systems SPEED AND QUALITY OF PLAY…GOLF AS IT SHOULD BE. You know Grund Guide for making premier yardage marking solutions. Now backed with the strength of Underhill® distribution and product development, you can have the highest quality and most complete yardage marking systems available today and into the future. Sprinkler Head Yardage Markers Model SPM 106 - TORO Engraved FITS:Toro 730, 750, 760, 780, 830/850S, 834S, 835S, Caps: Perfect-fit caps engraved and color DT34/35S. 854S. DT54/55, 860S, 880S filled for high visibility. Multiple number locations COLORS: Caps - l/m/l/l vary for lids with holes. Numbers - m/l/l/l/l/l/l Model SPM 107 - Rain Bird FITS: Rain Bird E900, E950, E700, E750, E500, E550, Engraved Caps: Perfect fit caps engraved 700, 751, 51DR and color filled for high visibility number COLORS: Caps - l/m/l/l identification. Numbers - m/l/l/l/l/l/l/l Model SPM 110 - Hunter FITS: Hunter G800, G900, G90 Engraved Caps/Covers: Perfect-fit COLORS: Flange cover / caps - l flange covers (G800, G900) and caps (G90), Numbers - m/l/l/l/l/l/l engraved and color filled for high visibility. Model SPM 101 - Fit Over Discs: FITS: Toro 630, 650, 660, 670, 680, 690, 830/850S, Anodized aluminum (no paint!), these 834S, 835S, DT34/35, 854S, 855S, DT54/55, 860S, markers are engraved and custom fit to each 880S, Rain Bird 47/51 DR, 71/91/95, E900, E950, sprinkler. Multiple number locations vary for lids E700, E750, E500, E550, 1100, Hunter G-70/75, with holes. -

A History of the French in London Liberty, Equality, Opportunity

A history of the French in London liberty, equality, opportunity Edited by Debra Kelly and Martyn Cornick A history of the French in London liberty, equality, opportunity A history of the French in London liberty, equality, opportunity Edited by Debra Kelly and Martyn Cornick LONDON INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Published by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU First published in print in 2013. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY- NCND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN 978 1 909646 48 3 (PDF edition) ISBN 978 1 905165 86 5 (hardback edition) Contents List of contributors vii List of figures xv List of tables xxi List of maps xxiii Acknowledgements xxv Introduction The French in London: a study in time and space 1 Martyn Cornick 1. A special case? London’s French Protestants 13 Elizabeth Randall 2. Montagu House, Bloomsbury: a French household in London, 1673–1733 43 Paul Boucher and Tessa Murdoch 3. The novelty of the French émigrés in London in the 1790s 69 Kirsty Carpenter Note on French Catholics in London after 1789 91 4. Courts in exile: Bourbons, Bonapartes and Orléans in London, from George III to Edward VII 99 Philip Mansel 5. The French in London during the 1830s: multidimensional occupancy 129 Máire Cross 6. Introductory exposition: French republicans and communists in exile to 1848 155 Fabrice Bensimon 7. -

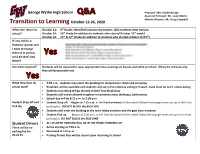

Transition to Learning October 12-26, 2020

George Wythe High School Principal: Mrs. Kimberly Ingo Assistant Principal: Mr. Jason Morris Athletic Director: Mr. Doug Campbell Transition to Learning October 12-26, 2020 When do I return to October 12: 9th Grade, identified-invitation by teacher, GED students, New Horizon school? October 19: 10th Grade (in addition to students who started October 12th week.) October 26: 11th & 12th Grade (in addition to students who started October 12/19th) If I my child is a Distance Learner and I want to change them to in person, can I do that? And When? Are mask required? Students will be required to wear appropriate face coverings on busses and while at school. If they do not have one, they will be provided one. What time does do 7:55 a.m. students may enter the building for temperature check and screening school start? Breakfast will be available and students will eat in the cafeteria eating 6 ft apart, mask must be worn unless eating. Students not eating will go directly to their first block class. Students will not be allowed to gather in commons areas (hallways, bathrooms) School day will be 8:15 a.m. to 2:00 p.m. Student Drop off and Student Drop off: Begins at 7:55 a.m. in the front entrance of the school follow the orange cones set up in the front Pick Up parking lot. DO NOT BLOCK the BUS LANE Students will enter the building at the main lobby entrance and the gym door entrance. Student Pick up: Begins at 2:00 p.m. -

British Royal Ancestry Book 6, Kings of England from King Alfred the Great to Present Time

GRANHOLM GENEALOGY BRITISH ROYAL ANCESTRY, BOOK 6 Kings of England INTRODUCTION The British ancestry is very much a patchwork of various beginnings. Until King Alfred the Great established England various Kings ruled separate parts. In most cases the initial ruler came from the mainland. That time of the history is shrouded in myths, which turn into legends and subsequent into history. Alfred the Great (849-901) was a very learned man and studied all available past history and especially biblical information. He came up with the concept that he was the 72nd generation descendant of Adam and Eve. Moreover he was a 17th generation descendant of Woden (Odin). Proponents of one theory claim that he was the descendant of Noah’s son Sem (Shem) because he claimed to descend from Sceaf, a marooned man who came to Britain on a boat after a flood. (See the Biblical Ancestry and Early Mythology Ancestry books). The book British Mythical Royal Ancestry from King Brutus shows the mythical kings including Shakespeare’s King Lair. The lineages are from a common ancestor, Priam King of Troy. His one daughter Troana leads to us via Sceaf, the descendants from his other daughter Creusa lead to the British linage. No attempt has been made to connect these rulers with the historical ones. Before Alfred the Great formed a unified England several Royal Houses ruled the various parts. Not all of them have any clear lineages to the present times, i.e. our ancestors, but some do. I have collected information which shows these. They include; British Royal Ancestry Book 1, Legendary Kings from Brutus of Troy to including King Leir. -

A Great Carolingian Panzootic

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stirling Online Research Repository TIMOTHY NEWFIELDa A great Carolingian panzootic: the probable extent, diagnosis and impact of an early ninth-century cattle pestilenceb Abstract This paper considers the cattle panzootic of 809-810, ‘A most enormous pestilence of oxen the most thoroughly documented and, as far as can be occurred in many places in Francia and discerned, spatially significant livestock pestilence of the 1 Carolingian period (750-950 CE). It surveys the written brought irrecoverable damage.’ evidence for the plague, and examines the pestilence’s spatial and temporal parameters, dissemination, diagnosis and impact. It is argued that the plague originated east of This reference to an epizootic in the Annales Fuldenses in 870 Europe, was truly pan-European in scope, and represented is one of roughly thirty-five encountered in the extant written a significant if primarily short-term shock to the Carolingian sources of Carolingian Europe.2 In total, mid eighth- through agrarian economy. Cattle in southern and northern Europe, mid tenth-century continental texts illuminate between ten including the British Isles, were affected. In all probability, and fourteen livestock plagues, the majority of which affec- several hundreds of thousands of domestic bovines died, ted cattle.3 In no earlier period of European history does the adversely impacting food production and distribution, and written record reveal so many epizootics.4 Cattle pestilences human health. A diagnosis of the rinderpest virus (RPV) is are reported in 801, 809-10, 820, 860, 868-70, 878, 939-42 tentatively advanced. -

A Viking-Age Settlement in the Hinterland of Hedeby Tobias Schade

L. Holmquist, S. Kalmring & C. Hedenstierna-Jonson (eds.), New Aspects on Viking-age Urbanism, c. 750-1100 AD. Proceedings of the International Symposium at the Swedish History Museum, April 17-20th 2013. Theses and Papers in Archaeology B THESES AND PAPERS IN ARCHAEOLOGY B New Aspects on Viking-age Urbanism, c. 750-1100 AD. Proceedings of the International Symposium at the Swedish History Museum, April 17–20th 2013 Lena Holmquist, Sven Kalmring & Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson (eds.) Contents Introduction Sigtuna: royal site and Christian town and the Lena Holmquist, Sven Kalmring & regional perspective, c. 980-1100 Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson.....................................4 Sten Tesch................................................................107 Sigtuna and excavations at the Urmakaren Early northern towns as special economic and Trädgårdsmästaren sites zones Jonas Ros.................................................................133 Sven Kalmring............................................................7 No Kingdom without a town. Anund Olofs- Spaces and places of the urban settlement of son’s policy for national independence and its Birka materiality Charlotte Hedenstierna-Jonson...................................16 Rune Edberg............................................................145 Birka’s defence works and harbour - linking The Schleswig waterfront - a place of major one recently ended and one newly begun significance for the emergence of the town? research project Felix Rösch..........................................................153 -

Family Group Sheet for Cnut the Great

Family Group Sheet for Cnut the Great Husband: Cnut the Great Birth: Bet. 985 AD–995 AD in Denmark Death: 12 Nov 1035 in England (Shaftesbury, Dorset) Burial: Old Minster, Winchester. Bones now in Winchester Cathedral Father: King Sweyn I Forkbeard Mother: Wife: Emma of Normandy Birth: 985 AD Death: 06 Mar 1052 in Winchester, Hampshire Father: Richard I Duke of Normandy Mother: Gunnor de Crepon Children: 1 Name: Gunhilda of Denmark F Birth: 1020 Death: 18 Jul 1038 Spouse: Henry III 2 Name: Knud III Hardeknud M Birth: 1020 in England Death: 08 Jun 1042 in England Burial: Winchester Cathedral, Winchester, England Notes Cnut the Great Cnut the Great From Wikipedia, (Redirected from Canute the Great) Cnut the Great King of all the English, and of Denmark, of the Norwegians, and part of the Swedes King of Denmark Reign1018-1035 PredecessorHarald II SuccessorHarthacnut King of all England Reign1016-1035 PredecessorEdmund Ironside SuccessorHarold Harefoot King of Norway Reign1028-1035 PredecessorOlaf Haraldsson SuccessorMagnus Olafsson SpouseÆlfgifu of Northampton Emma of Normandy Issue Sweyn Knutsson Harold Harefoot Harthacnut Gunhilda of Denmark FatherSweyn Forkbeard MotherSigrid the Haughty also known as Gunnhilda Bornc. 985 - c. 995 Denmark Died12 November 1035 England (Shaftesbury, Dorset) BurialOld Minster, Winchester. Bones now in Winchester Cathedral Cnut the Great, also known as Canute or Knut (Old Norse: Knútr inn ríki[1] (c. 985 or 995 - 12 November 1035) was a Viking king of England and Denmark, Norway, and parts of Sweden, whose successes as a statesman, politically and militarily, prove him to be one of the greatest figures of medieval Europe and yet at the end of the historically foggy Dark Ages, with an era of chivalry and romance on the horizon in feudal Europe and the events of 1066 in England, these were largely 'lost to history'.