Representation of Women in Laxman Mane's Upara

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter I Introduction CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION

Chapter I Introduction CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION 1.1 Preliminaries 1.2 Translation in English 1.3 Tradition of Translation in India 1.4 Tradition of Translation in Maharashtra 1.5 Linguistic Approach to Translation 1.6 Cultural Approach to Translation 1.7 History of Translation Studies in Europe 1.8 History of Translation Studies in India 1.9 Aims and Objectives 1.10 Hypothesis 1.11 Scope and Limitations of the Research 1.12 Justification for Research 1.13 Pedogogical Implications 1.1 Preliminaries This introductory chapter explains the different translations theories in India and the world. It also narrates the short history of translations in India and abroad. Though it is difficult to define translation in specific words, one can give various definitions to show the different ideas related to translations. Oxford dictionary of English language defines translation as ‘The action or process of turning something from one language into another”. It is true that dictionary is not basically meant to define terms like translation. Yet the dictionary has used the word ‘something’ which needs to be explained here. According to this defmition anything from a simple word to a work of art can be covered under this term translation. This covers a vast area and may mislead the basic concept of translation as we view it generally. Catford has defined it as “translation is the replacement of textual material of one language in another language”. According to this defmition material is replaced. A work of art does not contain only material. It has style and diction in it, which needs to be taken into consideration in translation. -

Pending at Institute (2Nd Installment) Candidate List Sr

Pending AT Institute (2nd Installment) Candidate List Sr. No. District Name Institute Application No Applicant Name 1 Ahmednagar Dharmaraj Shaikshanik Pratishthan's College of Pharmacy, Walki, Ahmednagar 1819DTR1000348739 Shraddha Sunil Nimase 2 Ahmednagar Dr. R.S. Gunjal Polytechnic, Gujalwadi,Sangamner 1819DTR1000340959 Sainath Dattatray Kharde 3 Ahmednagar Dharmaraj Shaikshanik Pratishthan's College of Pharmacy, Walki, Ahmednagar 1819DTR1000339049 Bhairav Santosh Jadhav 4 Ahmednagar Pravara Rural College of Engineering, Loni, Pravaranagar, Ahmednagar. 1819DTR1000335669 Ankush Ramchandra Kanwade 5 Ahmednagar Pravara Rural College of Engineering, Loni, Pravaranagar, Ahmednagar. 1819DTR1000335158 Samruddha Atul Deshmukh 6 Ahmednagar Pravara Rural College of Engineering, Loni, Pravaranagar, Ahmednagar. 1819DTR1000334539 Vishal Shridhar Shirsath 7 Ahmednagar Pravara Rural College of Engineering, Loni, Pravaranagar, Ahmednagar. 1819DTR1000331469 Vivek Bhaskar Ghorpade 8 Ahmednagar Pravara Rural College of Engineering, Loni, Pravaranagar, Ahmednagar. 1819DTR1000329706 Nilesh Manjabapu Shelke 9 Ahmednagar Pravara Rural College of Engineering, Loni, Pravaranagar, Ahmednagar. 1819DTR1000329399 Satendra Rampratap Sahni 10 Ahmednagar Pravara Rural College of Engineering, Loni, Pravaranagar, Ahmednagar. 1819DTR1000325333 Kunal Laxman Paul 11 Ahmednagar Pravara Rural College of Engineering, Loni, Pravaranagar, Ahmednagar. 1819DTR1000322902 Sagar Tatyaba Surashe 12 Ahmednagar Pravara Rural College of Engineering, Loni, Pravaranagar, Ahmednagar. 1819DTR1000322877 -

International Research Journal of Management Sociology & Humanities

International Research Journal of Management Sociology & Humanities ISSN 2277 – 9809 (online) ISSN 2348 - 9359 (Print) An Internationally Indexed Peer Reviewed & Refereed Journal Shri Param Hans Education & Research Foundation Trust www.IRJMSH.com www.SPHERT.org Published by iSaRa Solutions IRJMSH Vol 5 Issue 6 [Year 2014] ISSN 2277 – 9809 (0nline) 2348–9359 (Print) Representation of Anger and Agony in the writings of Marathi Dalit Writers Anuradha Sharma MA. MPhil. Assistant Professor Dalit literature fights for purgation of defiled social system. It deals not only with the themes of marginality and resistance but also explains about the Marxist changes influencing their condition. It is a living, breathing literary movement that is intent on establishing itself as an integral part of the field of Indian literature. Dalit literature protests against all forms of exploitation based on class, race, caste or occupation. It has not been recognized as a literature till 1970 but now its name is being heard all around the world. It has made the people to think against the exploitation and suppression. The rise of this literature marks a new chapter for India's marginalized class. Umpteen magazines, literary forums and workshops about Dalit came into existence because of this literature. Many well known Dalit writers are emerged from villages and towns. The poets, short story writers, novelists are receiving both exposure and opportunity in the marketplace that they have never before received. This chapter basically tries to focus on how the Dalit literature fights for purgation of defiled social system. To unfold the major and even minor complexities faced by them, Dalit literature came into existence. -

Cosmos Impact Factor 5.210

ISSN-L 0537-1988 UGC Approved Journal (Journal Number 46467, Sl. No. 228) (Valid till May 2018. All papers published in it were accepted before that date) Cosmos Impact Factor 5.210 56 THE INDIAN JOURNAL OF ENGLISH STUDIES An Annual Refereed Journal Vol. LVI 2019 Editor-in-Chief Dr. Chhote Lal Khatri Professor of English, T.P.S. College, Patna (Bihar) DSW, Patlipurta University, Patna (Bihar) The responsibility for facts stated, opinions expressed or conclusions reached and plagiarism, if any in this journal, is entirely that of the author(s). The editor/publisher bears no responsibility for them whatsoever. THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF ASSOCIATION FOR ENGLISH STUDIES OF INDIA 56 2019 THE INDIAN JOURNAL OF ENGLISH STUDIES Editor-in-Chief: Dr. Chhote Lal Khatri Professor of English, T.P.S. College, Patna (Bihar) DSW, Patlipurta University, Patna (Bihar) The Indian Journal of English Studies (IJES) published since 1940 accepts scholarly papers presented by the AESI members at the annual conferences of Association for English Studies of India (AESI). Orders for the copies of journal for home, college, university/departmental library may be sent to the Editor-in-Chief, Dr. Chhote Lal Khatri by sending an e-mail on [email protected]. Teachers and research scholars are requested to place orders on behalf of their institutions for one or more copies. Orders by post can be sent to the Editor- in-Chief, Indian Journal of English Studies, Anand Math, Near St. Paul School, Harnichak, Anisabad, Patna-800002 (Bihar) India. ASSOCIATION FOR ENGLISH STUDIES OF INDIA Price: ``` 350 (for individuals) ``` 600 (for institutions) £ 10 (for overseas) Submission Guidelines Papers presented at AESI (Association for English Studies of India) annual conference are given due consideration, the journal also welcomes outstanding articles/research papers from faculty members, scholars and writers. -

View Full Journal

Literary Voice U.G.C. Approved Peer-Reviewed Journal ISSN 2277-4521 Number 7 Volume I September 2017 The Bliss and Wonder of Childhood Experience in Mulk Raj Anand's Seven Summers/ 5 Dr. Basavaraj Naikar Non-Scheduled Languages of Uttarakhand As Reflection of Rich Cultural Patterns/24 Dr. H.S. Randhawa Bama's Karukku :Voice and Vision from the Periphery /35 Dr. Kshamata Chaudhary Amitav Ghosh's The Hungry Tide:An Eco Critical Perspective/43 Dr Anupama S. Pathak Kittur through Literary Narration:Basavaraj Naikar's The Queen of Kittur/ 51 Dr Sumathi Shivakumar Socio-Economic Tumult in Rupa Bajwa's Tell Me a Story/ 59 Dr. Priyanka Sharma “Jat Panchayat” in Kaikadi Community: Laxman Mane's An Outsider/ 68 Dr. Smita R.Nigori Diasporic Concerns in Bharati Mukherjee's Desirable Daughters / 74 Shweta Chauhan, Dr. Tanu Gupta Slang and Indian Students: Reflections on the Changing Face of English/79 Manpreet Kaur Decoding the Decay of Nature in Art: A Study of Anthony Goicolea's Paintings/86 Baljeet Kaur An Odyssey of Feminism from Past to the Cyborgian Age/94 Navdeep Kaur Book Reviews Editorial Note Literary Voice September 2017 offers a variegated cerebral Renee Singh, Sacred Desire. Ludhiana. Aesthetic Publications, feast—from the delightful childhood experiences of Mulk Raj 2015, pp. 127, Rs. 250/ 106 Anand, in Seven Summers, narrated from the vantage point of the Dr. Supriya Bhandari writer's mature, philosophical and psychological knowledge and N.K. Neb. The Flooded Desert : A Novel. New Delhi. Authorpress, its resonance in fictional representations meticulously analyzed 2017, pp. 231, Rs. -

Varsha Adalja Tr. Satyanarayan Swami Pp.280, Edition: 2019 ISBN

HINDI NOVEL Aadikatha(Katha Bharti Series) Rajkamal Chaudhuri Abhiyatri(Assameese novel - A.W) Tr. by Pratibha NirupamaBargohain, Pp. 66, First Edition : 2010 Tr. Dinkar Kumar ISBN 978-81-260-2988-4 Rs. 30 Pp. 124, Edition : 2012 ISBN 978-81-260-2992-1 Rs. 50 Ab Na BasoIh Gaon (Punjabi) Writer & Tr.Kartarsingh Duggal Ab Mujhe Sone Do (A/w Malayalam) Pp. 420, Edition : 1996 P. K. Balkrishnan ISBN: 81-260-0123-2 Rs.200 Tr. by G. Gopinathan Aabhas Pp.180, Rs.140 Edition : 2016 (Award-winning Gujarati Novel ‘Ansar’) ISBN: 978-81-260-5071-0, Varsha Adalja Tr. Satyanarayan Swami Alp jivi(A/w Telugu) Pp.280, Edition: 2019 Rachkond Vishwanath Shastri ISBN: 978-93-89195-00-2 Rs.300 Tr.Balshauri Reddy Pp 138 Adamkhor(Punjabi) Edition: 1983, Reprint: 2015 Nanak Singh Rs.100 Tr. Krishan Kumar Joshi Pp. 344, Edition : 2010 Amrit Santan(A/W Odia) ISBN: 81-7201-0932-2 Gopinath Mohanti (out of stock) Tr. YugjeetNavalpuri Pp. 820, Edition : 2007 Ashirvad ka Rang ISBN: 81-260-2153-5 Rs.250 (Assameese novel - A.W) Arun Sharma, Tr. Neeta Banerjee Pp. 272, Edition : 2012 Angliyat(A/W Gujrati) ISBN 978-81-260-2997-6 Rs. 140 by Josef Mekwan Tr. Madan Mohan Sharma Aagantuk(Gujarati novel - A.W) Pp. 184, Edition : 2005, 2017 Dhiruben Patel, ISBN: 81-260-1903-4 Rs.150 Tr. Kamlesh Singh Anubhav (Bengali - A.W.) Ankh kikirkari DibyenduPalit (Bengali Novel Chokher Bali) Tr. by Sushil Gupta Rabindranath Tagorc Pp. 124, Edition : 2017 Tr. Hans Kumar Tiwari ISBN 978-81-260-1030-1 Rs. -

Understanding Novel (Special English)

SHIVAJI UNIVERSITY, KOLHAPUR CENTRE FOR DISTANCE EDUCATION Understanding Novel (Special English) B. A. Part-III (Semester-V Paper-X) (Academic Year 2015-16 onwards) Unit-1 Realistic Novel and Science Fiction 1.1 Realistic Novel Content: 1.1.1 Objectives 1.1.2 Introduction 1.1.3 Definitions of Realistic Novel 1.1.4 Features of Realistic Novel 1.1.5 Prominent Writers in the Tradition 1.1.6 Attack on Realistic Novel 1.1.7 Glossary and Notes 1.1.8 Check Your Progress 1.1.9 Exercises 1.1.10 Answers to Check Your Progress 1.1.11 References for Further Reading 1.1.1 Objectives: G To understand the concept of Realistic Novel in English G To know the emergence and development of Realistic Novel G To define the Realistic Novel G To discuss the features of Realistic Novel G To take the survey of prominent writers in the tradition of Realistic Novel 1.1.2 Introduction: Realism in literature is associated with the realist art movement that emerged during mid-19 th century France and Russia as a reaction against the classical demands of creative writings that attempted to show life as it should be as well as 1 against the idealistic conceptions of Romantic writings. It was firstly used by Friedrich Schiller in his letter to Goethe where he writes, “realism cannot make a poet.” Further, in the work entitled Ideen , Schlegel pointed out that “all philosophy is idealism and there is no true realism except that of poetry.” Since then, the term is applied to the works of literature that deal with the new approach to character and subject matter, where stories reflect real life and fictional characters demonstrate as if they are real characters. -

4.107 M.A.(Hons.) in English & with Research Sem

SYLLABUS M.A. Honours in English & M.A. Honours with Research in English (For the Academic Year - 2017-18) M.A. Part II Semester III Sr.No. Courses Group Paper No. Name of the Paper 1 Elective 1 IX (A) Genre Studies: Poetry IX (B) Indian Literature in translation 2 Elective 2 X (A) Genre Studies: Prose Fiction X (B) Introduction to Subaltern Studies 3 Elective 3 XI (A) Genre Studies: Drama XI (B) Re-Reading Canonical Literature XI (C) South Asian Literature 4 Elective 4 XII (A) Contemporary British Literature XII (B) Politics, Ideology and English Studies XII (C) ELT 5 Elective 5 XIII (A) American Literature XIII (B) Australian Literature XIII (C) Canadian Literature University of Mumbai Syllabus for M.A. Honours and M.A. Honours with Research in English Part – II - Semester: III Course: Elective Group - 1 Course Title: Genre Studies: Poetry Paper: IX (A) (Choice Based Credit System with effect from the Academic Year 2017-18) 1. Syllabus as per Choice Based Credit System i) Name of the Program : M.A. Honours and M.A. Honours with Research in English ii) Course Code : PAENGHR301 iii) Course Title : Genre Studies: Poetry iv) Semester wise Course Contents : Enclosed the copy of syllabus v) References and Additional References : Enclosed in the Syllabus vi) Credit Structure : No. of Credits per Semester -06 vii) No. of lectures per Unit : 15 viii) No. of lectures per week : 04 ix) No. of Tutorials per week : 01 2. Scheme of Examination : 4 Questions of 15 marks each 3. Special notes , if any : No 4. -

List of Certified Energy Auditors

LIST OF CERTIFIED ENERGY AUDITORS S No Regn No Name of the Candidate IST EXAM - MAY 2004 1 EA-0001 Atul Pratap Singh 2 EA-0007 Padmanabha Ramanuja Chari 3 EA-0009 Jitendra Jain 4 EA-0011 G Rudra Narsimha Rao 5 EA-0012 Pradeep Shrikrishna Lothe 6 EA-0015 Ram Kumar Yadav 7 EA-0016 Prabir Chattoraj 8 EA-0019 Aswini Kumar Sahu 9 EA-0021 Hitendera Mehtani 10 EA-0028 Premkumar 11 EA-0029 Subesh Kumar 12 EA-0030 L Rafique Ali 13 EA-0032 Pramod Kumar Dangaich 14 EA-0035 I Thanumoorthi 15 EA-0036 Devesh Kumar Singhal 16 EA-0038 T Senthil Kumar 17 EA-0043 Anand Narayan Kale 18 EA-0044 G V Jagadeesh Kumar 19 EA-0045 P Chandramouli 20 EA-0046 Deepak Kaushik 21 EA-0055 Rajeev Kumar Pahwa 22 EA-0061 Vishnu J Mulchandani 23 EA-0064 Babu M 24 EA-0075 Dilip Sarda 25 EA-0077 J Swaminathan 26 EA-0081 Mahendra Manohar Dandekar 27 EA-0083 Avinash Kumar 28 EA-0086 M Bhaskar 29 EA-0092 Dhirendra Bansal 30 EA-0104 Pande Madhav 31 EA-0108 Rakesh Sahay 32 EA-0114 Dipak Kumar Bhattacharya 33 EA-0115 Manu Chawla 34 EA-0119 Shishir Saxena 35 EA-0122 Amar Gupta 36 EA-0128 Mukul Ghanekar 37 EA-0132 Binobananda Jha 38 EA-0133 Ramesh Babu Guptha Paluri 39 EA-0136 Sukuru Ramarao 40 EA-0142 Sanjay Bhanudasrao Joshi 41 EA-0148 Mahesh Kumar Madan 42 EA-0149 Swapan Kumar Dutta 43 EA-0155 Desai Gaurang 44 EA-0157 Raj Kumar Porwal 45 EA-0159 Devanand Patil 46 EA-0160 Achyuta Nanda Mohanty 47 EA-0178 Mahesh Chandani 48 EA-0179 R K Aggarwal 49 EA-0183 G Pasupathy 50 EA-0184 Sandeep Kumar Jain 51 EA-0185 B D Gupta 52 EA-0187 Mohammad Abul Kalam 53 EA-0191 Arun Kanti Bala 54 EA-0192 G Sankar 55 EA-0200 R Balasubramanian 56 EA-0203 V Kumaran 57 EA-0205 Sarvesh Kumar 58 EA-0207 C Sethuraman 59 EA-0216 Pramath Sanghavi 60 EA-0220 Pawan B Agarwal 61 EA-0223 Subrat Kishore Nayak 62 EA-0232 Upendra Pratap Singh 63 EA-0233 Shailendra Pandey 64 EA-0236 Tukaram K. -

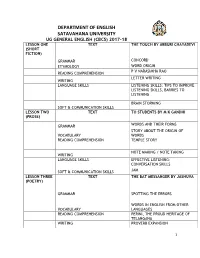

SU English Syllabus, Old and New.Pdf

DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH SATAVAHANA UNIVERSITY UG GENERAL ENGLISH (CBCS) 2017-18 LESSON ONE TEXT THE TOUCH BY ABBURI CHAYADEVI (SHORT FICTION) GRAMMAR CONCORD ETYMOLOGY WORD ORIGIN P V NARASIMHA RAO READING COMPREHENSION LETTER WRITING WRITING LANGUAGE SKILLS LISTENING SKILLS: TIPS TO IMPROVE LISTENING SKILLS, BARRIES TO LISTENING BRAIN STORMING SOFT & COMMUNICATION SKILLS LESSON TWO TEXT TO STUDENTS BY M K GANDHI (PROSE) GRAMMAR WORDS AND THEIR FORMS STORY ABOUT THE ORIGIN OF VOCABULARY WORDS READING COMPREHENSION TEMPLE STORY NOTE MAKING / NOTE TAKING WRITING LANGUAGE SKILLS EFFECTIVE LISTENING: CONVERSATION SKILLS SOFT & COMMUNICATION SKILLS JAM LESSON THREE TEXT THE BAT MESSANGER BY JASHUVA (POETRY) GRAMMAR SPOTTING THE ERRORS WORDS IN ENGLISH FROM OTHER VOCABULARY LANGUAGES READING COMPREHENSION PERINI, THE PROUD HERITAGE OF TELANGANA WRITING PROVERB EXPANSION 1 LANGUAGE SKILLS READING SKILLS: SKIMMING AND SCANNING SOFT & COMMUNICATION SKILLS ORAL PRESENTATION LESSSON FOUR TEXT RAMANUJAN BY PARTAP SEHGAL (DRAMA) GRAMMAR PUTTING JUMBLED WORDS AND SENTENCES IN ORDER VOCABULARY DERIVATION READING COMPREHENSION MIMICRY PARAGRAPH WRITING / ESSAY WRITING WRITING LANGUAGE SKILLS CONVERSATION SKILLS SOFT & COMMUNICATION SKILLS DIALOGUE WRITING LESSON FIVE TEXT ARJUN BY MAHASWETHA DEVI (SHORT FICTION) SENTENCE COMPLETION GRAMMAR WORD FORMATION VOCABULARY READING COMPREHENSION YADI SADASHIVA, A GENIUS PAR EXCELLENCE E-CORRESPONDENCE: E-MAILS WRITING LANGUAGE SKILLS TELEPHONE CONVERSATION SOFT & COMMUNICATION SKILLS ROLE PLAY LESSON SIX TEXT WOMEN -

POSTCOLONIAL LITERATURES (An International Refereed Biannual Published in June and December)

ESTD. 2000 INDIAN JOURNAL OF Red. No. KERENGO1377/11/1/99 -TC POSTCOLONIAL LITERATURES (An International Refereed Biannual Published in June and December) Vol. 17.1 (June 2017) ISSN 0974 - 7370 Indian Journal of Post Colonial Literatures is an official research IJPCL Vol. 17.1(June2017) Vol. IJPCL publication of the Post Graduate and Research Department. of English, Newman College, Thodupuzha. Ever since its inception in the year 2000, it is being published biannually in the months of June and December. It is devoted to the studies on Postcolonial Literatures and publishes original and creative works, articles, notes, reviews, and essays. It is intended to promote and augment research mindset among professionals, scholars, researchers and students. The major objective of this journal is to explore and ex- plicate the theoretical perceptions, cultural implications and con- temporary relevance of Postcolonial Literatures. June 2017 POST GRADUATE & RESEARCH DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH NEWMAN COLLEGE THODUPUZHA, KERALA, INDIA Vol. 17 No. 1 (June 2017) ISSN 0974-7370 INDIAN JOURNAL OF POSTCOLONIAL LITERATURES (An International Refereed Biannual Published in June and December) CENTRE FOR ENGLISH STUDIES AND RESEARCH NEWMAN COLLEGE THODUPUZHA - 685 585 KERALA, INDIA CONTENTS Kamala Das: A Confessional Ecofeminist 5 - Amstrong Sebastian Belonging and Displacement in Caryl Phillips’s A Distant Shore 14 - Roshni C A Transcultural Re-reading of Black Experience in the Poems of Gwendolyn Brooks and Benjamin Zephaniah 22 - Nisha Mathew The Silent Voices of the African Woman in BuchiEmecheta’s The Bride Price 31 - Divya Johnson Colonial Resistance in Sara Joseph’s Gift in Green 37 - Kripa Vijayan Mapping the Ecological Consciousness in Select Australian Aboriginal Poems 42 - Asha P. -

LITERARY ENDEAVOUR a Quarterly International Refereed Journal of English Language, Literature and Criticism VOL

www.literaryendeavour.org ISSN 0976-299X LITERARY ENDEAVOUR A Quarterly International Refereed Journal of English Language, Literature and Criticism VOL. IX NO. 1 JANUARY 2018 UGC Approved Under Arts and Humanities Journal No. 44728 CONTENTS No. Title & Author Page No. 1. Italian Poetry in the Modern Time - 1900 to Post Second World War 01-03 - Dr. Lilly Fernandes and Mr Mussie Tewelde 2. The Endless Exodus: A Journey through Ayyappa Paniker's Southbound 04-07 - Anusree R. Nair 3. Ramanujan's Poetry: A Realistic Perspective 08-10 - Ishfaq Hussain Bhat 4. The Poetry of Emily Dickinson: An Interior Journey 11-13 - G. Aravind and Dr. S. Ravikumar 5. Exploring 'Patriotism' in Chinua Achebe's Things Fall Apart 14-17 - Dr. Rosaline Jamir 6. Contextualizing Post Colonial Identities in Rudyard Kipling's Kim 18-22 - Dr. Pragti Sobti 7. Value vs. Value: An Axiological Study of Sudha Murthy's Dollar Bahu 23-27 - Dr. Mukta Jagannath Mahajan 8. Ambivalence about Masculine Ideals: Some Observations on Ethiopian 28-34 Masculinity/ ies, Literature and Culture - Tripti Karekatti 9. Narrating Dreams and Daughters: Githa Hariharan's The Thousand Faces 35-41 of Night and Manju Kapur's Difficult Daughters - Dr. Arpita Ghosh 10. Notes from The Underground: The Insights of the Insane 42-46 - Sanjay Kumar 11. Dorothy West's Views on Social Stratification of African Americans in 47-52 The United States of America - Kukatlapalli Subbarayudu 12. An Approach and Practice to Writing English Novels on Lesbianism: 53-59 A Study of Post-modern Indian Women Novelists from Late Twentieth to Present Century - Dipak Giri 13.