Analysis of the Grassroots Resistance Movement Against Goldmining in the Villages of Bergama, Turkey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poverty and Social Exclusion of Roma in Turkey

Başak Ekim Akkan, Mehmet Baki Deniz, Mehmet Ertan Photography: Başak Erel Poverty and Social Exclusion of Roma in Turkey spf sosyal politika forumu . Poverty and Social Exclusion of Roma in Turkey Published as part of the Project for Developing Comprehensive Social Policies for Roma Communities Başak Ekim Akkan, Mehmet Baki Deniz, Mehmet Ertan Photography: Başak Erel . Editor: Taner Koçak Cover photograph: Başak Erel Cover and page design: Savaş Yıldırım Print: Punto Print Solutions, www.puntops.com First edition, November 2011, Istanbul ISBN: 978-605-87360-0-9 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without the written permission of EDROM (Edirne Roma Association), Boğaziçi University Social Policy Forum and Anadolu Kültür. COPYRIGHT © November 2011 Edirne Roma Association (EDROM) Mithat Paşa Mah. Orhaniye Cad. No:31 Kat:3 Edirne Tel/Fax: 0284 212 4128 www.edrom.org.tr [email protected] Boğaziçi University Social Policy Forum Kuzey Kampus, Otopark Binası Kat:1 No:119 34342 Bebek-İstanbul Tel: 0212 359 7563-64 Fax: 0212 287 1728 www.spf.boun.edu.tr [email protected] Anadolu Kültür Cumhuriyet Cad. No:40 Ka-Han Kat:3 Elmadağ 34367 İstanbul Tel/Fax: 0212 219 1836 www.anadolukultur.org [email protected] The project was realized with the financial support of the European Union “European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights (EIDHR)” program. The Swedish Consulate in Istanbul also provided financial support to the project. The contents of this book do not reflect the opinions of the European Union. -

A Place at the Table: a Sierra Roundtable on Race And

THE OF AN AMERICAN ENVIRONMENTAL MOVEMENT DOMINATED OF WHITE THE BY THE INTERESTS PEOPLE IS OVER BEGINNING OF THE END CAME IN SEPTEMBER 1982 AN WARREN COUNTY NORTH CAROLINA WHEN MORE THAN 500 PREDOMINANTLY AFRICANAMERICAN RESIDENTS WERE ARRESTED FOR OF TRUCKS BLOCKING THE PATH CARRYING TOIOC PCBS TO NEWLY DESIGNATED HAZ ARDOUSWANC AMONG THOSE TAKEN INTO CUSTODYWAS THE REVEREND BENJAMIN CHAVIS EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF THE UNITED CHURCH OF CHRIST COMMISSION FOR RACIAL JUSTICE CRJ HIS SUSPICIONS AS TO WHY NORTH CAROLINA WOULD CHOOSE BLACK COMMUNITY AS DUMP FOR ITS POISON WERE CONFIRMED IN MILESTONE REPORT BY THE CRJ IN 1987 WHICH DEMON STRATED THAT THE SINGLE MOST SIGNIFI CANT FACTOR IN THE SITING OF HAZARDOUSWASTE FACILITIES NATIONWIDE WAS RACE SUBSEQUENT REPORT BY THE NATIONAL LAWJOURNAL FOUND THAT THE EPA TOOK 20 PERCENT LONGER TO IDEN TIFY SUPERFUND SITES IN MINORITY FL OF COMMUNITIES AND THAT POLLUTERS EJJ THOSE NEIGHBORHOODS WERE FINED ONLY HALF AS MUCH AS POLLUTERS OF WHITE ONES ARMEDWITH PROOF OF WHAT HAS BECOME KNOWN AS II ATT COOSEENVIRONMENTAL RACISM ALLIANCE OF CHURCH LABOR CIVIL RIGHTS AND COMMUNITY OF COLOR AROSE TO DEMAND ENVIRONMENTAL GROUPS LED BY PEOPLE JUSTICE PART OF DOING SO MEANT CONFRONTING THE SOCALLED GROUP OFTEN THE NA TIONS LARGESTAND LARGELY WHITEENVIRONMENTAL GROUPS AND BLUNTLY ACCUSING THEM OF RACISM FROM THE CHARGES CAME IN EARLY 1990 IN JOLTING SERIES OF LETTERS LOUISIANAS GULF COAST TENANT LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT PROJECT AND THE SOUTHWEST ORGANIZING PROJECT IN ALBUQUERQUE SEE THE LETTER THAT SHOOK MOVEMENTPAGE -

Caveat Emptor Collecting and Processing Pottery in Western Rough Cilicia?

Caveat Emptor Collecting and Processing Pottery in Western Rough Cilicia? Nicholas Rauh Richard Rothaus February 19, 2018 This paper1 furnishes a preliminary assessment of the field and laboratory pro- cedures used to obtain ceramic field data by the participants of Rough Cilicia Archaeological Survey Project in western Rough Cilicia (Gazipasha District, An- talya Province, south coastal Turkey). Between 1996 and 2004 the pedestrian team of the Rough Cilicia Survey conducted pottery collections and otherwise processed field pottery as its principal operation. Through nine consecutive field seasons the pedestrian team identified and processed an aggregate of7313 sherds, revealing the following preliminary breakdown of ceramic data as shown in Table One in Appendix. What concerns us here is not so much the historical significance of this data as the means by which it was acquired. Since the data results from an evolving array of procedures employed by dozens of participants working through multi- 1A more detailed presentation of the data is furnished in Table Two at the end of this ar- ticle. The presentation of this data requires some explanation. Datable sherds were recorded according to known typologies: these consisted almost exclusively of imported fine ware and amphora remains for which chronological information was available from published archaeo- logical contexts at sites throughout the Mediterranean world. In some instances, chronologies of a few locally produced forms such as the Pinched-handle, Koan style, and Pamphylian amphoras, were known from published finds of similar forms, again, identified elsewhere in the Mediterranean. In the accompanying tables, ceramics remains from recognized typologies have been arranged according to the following categories: “Pre Roman” (8th-1st centuries BC); “Early Roman” (1st-3rd centuries AD); “Late Roman” (4th-7th centuries AD); “Byzantine” (for this region, generally 9th-12th centuries AD). -

Hadrian and the Greek East

HADRIAN AND THE GREEK EAST: IMPERIAL POLICY AND COMMUNICATION DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Demetrios Kritsotakis, B.A, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Fritz Graf, Adviser Professor Tom Hawkins ____________________________ Professor Anthony Kaldellis Adviser Greek and Latin Graduate Program Copyright by Demetrios Kritsotakis 2008 ABSTRACT The Roman Emperor Hadrian pursued a policy of unification of the vast Empire. After his accession, he abandoned the expansionist policy of his predecessor Trajan and focused on securing the frontiers of the empire and on maintaining its stability. Of the utmost importance was the further integration and participation in his program of the peoples of the Greek East, especially of the Greek mainland and Asia Minor. Hadrian now invited them to become active members of the empire. By his lengthy travels and benefactions to the people of the region and by the creation of the Panhellenion, Hadrian attempted to create a second center of the Empire. Rome, in the West, was the first center; now a second one, in the East, would draw together the Greek people on both sides of the Aegean Sea. Thus he could accelerate the unification of the empire by focusing on its two most important elements, Romans and Greeks. Hadrian channeled his intentions in a number of ways, including the use of specific iconographical types on the coinage of his reign and religious language and themes in his interactions with the Greeks. In both cases it becomes evident that the Greeks not only understood his messages, but they also reacted in a positive way. -

Christians and Jews in Muslim Societies

Arabic and its Alternatives Christians and Jews in Muslim Societies Editorial Board Phillip Ackerman-Lieberman (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, USA) Bernard Heyberger (EHESS, Paris, France) VOLUME 5 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/cjms Arabic and its Alternatives Religious Minorities and Their Languages in the Emerging Nation States of the Middle East (1920–1950) Edited by Heleen Murre-van den Berg Karène Sanchez Summerer Tijmen C. Baarda LEIDEN | BOSTON Cover illustration: Assyrian School of Mosul, 1920s–1930s; courtesy Dr. Robin Beth Shamuel, Iraq. This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Murre-van den Berg, H. L. (Hendrika Lena), 1964– illustrator. | Sanchez-Summerer, Karene, editor. | Baarda, Tijmen C., editor. Title: Arabic and its alternatives : religious minorities and their languages in the emerging nation states of the Middle East (1920–1950) / edited by Heleen Murre-van den Berg, Karène Sanchez, Tijmen C. Baarda. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, 2020. | Series: Christians and Jews in Muslim societies, 2212–5523 ; vol. -

Remedying Environmental Racism

Michigan Law Review Volume 90 Issue 2 1991 Remedying Environmental Racism Rachel D. Godsil University of Michigan Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Environmental Law Commons, and the Law and Race Commons Recommended Citation Rachel D. Godsil, Remedying Environmental Racism, 90 MICH. L. REV. 394 (1991). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol90/iss2/3 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTES Remedying Environmental Racism Rachel D. Godsil In 1982, protesters applied the techniques of nonviolent civil diso bedience to a newly recognized form of racial discrimination. 1 The protesters, both black and white, attempted to prevent the siting of a polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB)2 landfill in predominantly black War ren County, North Carolina.3 In the end, the campaign failed. None theless, it focused national attention on the relationship between pollution and minority communities4 and prompted the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) to study the racial demographics of hazard ous waste sites. s The GAO report found that three out of the four commercial haz ardous waste landfills in the Southeast United States were located in 1. Charles Lee, Toxic Waste and Race in the United States, in THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE MICHIGAN CONFERENCE ON RACE AND THE INCIDENCE OF ENVIRONMENTAL HAZARDS 6, 8 (Paul Mohai & Bunyan Bryant eds., 1990) [hereinafter ENVIRONMENTAL HAZARDS]. -

Bölüm Adı : SANAT TARİHİ

Bölüm Adı : SANAT TARİHİ Tüm Dönemler EDSTN 217 - Arkeoloji Anadolu Uyg-III - Kredi: 2( T : 2 - U : 0 ) - AKTS : 4 Paleolitik /Epipaleolitik Dönem ve Özellikleri , Anadolu dışındaki önemli Paleolitik Merkezler(Alatamira ve Lascaux Mağaraları) , Anadoludaki Paleolitik dönem mağaralarından örnekler( Karain, Öküzini Yarımburgaz, Dülük, Palanlı Kaletepe vd.) , Anadoludaki Paleolitik Dönem yerleşmeleri , Mezolitik Çağ ve bu döneme ait yerleşim alanları , Aseramik /Erken Neolitik Çağ Yerleşmeleri , Madenin kullanımı , Erken Neolitik Dönem (seramiksiz dönem) ve Natuf Kültürü , Erken Neolitik Çağ Yerleşmeleri (Göbeklitepe, Hallan Çemi,Nevala Çori, Çayönü,Aşıklı höyük , Çayönü ve madenin kullanımı konut mimarisinin gelişimi , Çatalhöyük Seramiksiz ve seramikli dönem , Çatal Höyükte Konut Mimarisi , Ölü Gömme ve Ata Kültü geleneği , Çatalhöyük Konutlarındaki Kültsel yapılar ve din olgusu , EDSTN 449 - Çağdaş Sanat-I - Kredi: 2( T : 2 - U : 0 ) - AKTS : 5 Neoklasizm ve realizm , Romantizm , Empresyonizm , Sembolizm , Ekspresyonizm , Bauhaus , Fovizm , ARA SINAV , Kübizm , Fütürizm , Dadaizm , Konstrüktivizm , Süpremaztizm , De Stijl Grubu ve Sürrealizm , EDSTN 219 - Ortaçağ İslam Sanatı-III - Kredi: 2( T : 2 - U : 0 ) - AKTS : 4 Karahanlı Dönemi hakkında genel bilgi ve yapı grupları ile genel özellikleri , Karahanlı Dönemi Türkistan Camileri (Çilburç, Başhane, Dehistan,) , Talhatan Baba, Buhara Namazgah Magaki Attari camileri , Karahanlı Minareleri Burana, Kalan minareleri) , Can kurgan Vabkent minareleri , Karahanlı türbeleri (Tim Arap Ata, Ayşe Bibi) , Özkent Türbeleri, Şeyh Fazıl Türbesi , Karahanlı Hanları (Manakeldi, Daye Hatun) , Akçakale, Dehistan Hanları , Karahanlı Dönemi taşınabilir eserlerden örnekler , Gazneli dönemi minareleri (III. Mesut Sultan Mahmut Minareleri) , Gazneli Türbeleri (Aslancazip, Babahatim) , Gazneli dönemi sarayları (Leşger-i Bazar, III. Mesut) , Gazneli dönemi taşınabilir eserlerden örnekler , EDSTN 237 - Bizans Sanatı I - Kredi: 2( T : 2 - U : 0 ) - AKTS : 4 Byzansolojinin ortaya çıkışı , anlamı, gelişmi. -

The Influence of Achaemenid Persia on Fourth-Century and Early Hellenistic Greek Tyranny

THE INFLUENCE OF ACHAEMENID PERSIA ON FOURTH-CENTURY AND EARLY HELLENISTIC GREEK TYRANNY Miles Lester-Pearson A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2015 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/11826 This item is protected by original copyright The influence of Achaemenid Persia on fourth-century and early Hellenistic Greek tyranny Miles Lester-Pearson This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of St Andrews Submitted February 2015 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, Miles Lester-Pearson, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 88,000 words in length, has been written by me, and that it is the record of work carried out by me, or principally by myself in collaboration with others as acknowledged, and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September 2010 and as a candidate for the degree of PhD in September 2011; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2010 and 2015. Date: Signature of Candidate: 2. Supervisor’s declaration: I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of PhD in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

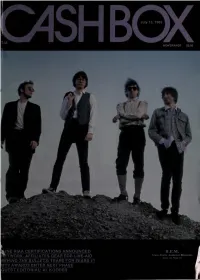

Cashbox Subscription: Please Check Classification;

July 13, 1985 NEWSPAPER $3.00 v.'r '-I -.-^1 ;3i:v l‘••: • •'i *. •- i-s .{' *. » NE RIAA CERTIFICATIONS ANNOUNCED R.E.M. AFFILIATES LIVE-AID Crass Roots Audience Blossoms TWORK, GEAR FOR Story on Page 13 WEHIND THE BULLETS: TEARS FOR FEARS #1 MTV AWARDS ENTER NEXT PHASE GUEST EDITORIAL: AL KOOPER SUBSCRIPTION ORDER: PLEASE ENTER MY CASHBOX SUBSCRIPTION: PLEASE CHECK CLASSIFICATION; RETAILER ARTIST I NAME VIDEO JUKEBOXES DEALER AMUSEMENT GAMES COMPANY TITLE ONE-STOP VENDING MACHINES DISTRIBUTOR RADIO SYNDICATOR ADDRESS BUSINESS HOME APT. NO. RACK JOBBER RADIO CONSULTANT PUBLISHER INDEPENDENT PROMOTION CITY STATE/PROVINCE/COUNTRY ZIP RECORD COMPANY INDEPENDENT MARKETING RADIO OTHER: NATURE OF BUSINESS PAYMENT ENCLOSED SIGNATURE DATE USA OUTSIDE USA FOR 1 YEAR I YEAR (52 ISSUES) $125.00 AIRMAIL $195.00 6 MONTHS (26 ISSUES) S75.00 1 YEAR FIRST CLASS/AIRMAIL SI 80.00 01SHBCK (Including Canada & Mexico) 330 WEST 58TH STREET • NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10019 ' 01SH BOX HE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC / COIN MACHINE / HOME ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY VOLUME XLIX — NUMBER 5 — July 13, 1985 C4SHBO( Guest Editorial : T Taking Care Of Our Own ^ GEORGE ALBERT i. President and Publisher By A I Kooper MARK ALBERT 1 The recent and upcoming gargantuan Ethiopian benefits once In a very true sense. Bob Geldof has helped reawaken our social Vice President and General Manager “ again raise an issue that has troubled me for as long as I’ve been conscience; now we must use it to address problems much closer i SPENCE BERLAND a part of this industry. We, in the American music business do to home. -

On the Road from Environmental Racism to Environmental Justice

Volume 5 Issue 2 Article 6 1994 On the Road from Environmental Racism to Environmental Justice Maria Ramirez Fisher Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/elj Part of the Environmental Law Commons Recommended Citation Maria R. Fisher, On the Road from Environmental Racism to Environmental Justice, 5 Vill. Envtl. L.J. 449 (1994). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/elj/vol5/iss2/6 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Villanova Environmental Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Fisher: On the Road from Environmental Racism to Environmental Justice 1994] ON THE ROAD FROM ENVIRONMENTAL RACISM TO ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE We're not saying to take the incinerators and the toxic- waste dumps out of our communities and put them in white communities-we're saying they should not be in anybody's community.... You can't get justice by doing an injustice on somebody else. When you have lived through suffering and hardship, you want to remove them, not only from your own people but from all peoples.' I. INTRODUCTION The environmental movement invariably has focused on tradi- tional areas of environmentalism which include wilderness and 2 wildlife preservation, pollution, conservation, and overpopulation. Presently, however, the environmental movement is entering a new stage of activism, that of social justice, in response to charges of environmental racism.3 Environmental racism occurs when people of color disproportionately bear the burdens and risks of environ- 1. -

W W W . D I K I L I T D I O S B . O R G

www.dikilitdiosb.org.tr Dikili Agricultural Greenhouse Specialized Organized Industrial Zone Supported, Developed, The products are packed, The products are processed, The products are preserved, Agricultural and industrial integration is developed, Sustainable, suitable and high-quality raw materials are provided to increase competitiveness. Dikili Agricultural Greenhouse Specialized Organized Industrial Zone 3 of all the 28 Specialized Organized Industrial Zone Based On Agriculture are Geothermal Sourced Specialized Organized Industrial Zones Based On Agriculture. Geothermal Sourced TDİOSBs are: Denizli/Sarayköy Greenhouse TDİOSB: 718.000 m² Ağrı/Diyadin Greenhouse TDİOSB: 1.297.000 m² In Turkey there are 28 Specialized Organized Industrial İzmir / Dikili Greenhouse TDİOSB: 3.038.894,97 m² Zone Based On Agriculture. İzmir Dikili TDİOSB has the biggest area of Greenhouse TDİOSB with numer 21 registration in Turkey. 3.038.894,97 m² Bergama Organized Industrial Zone Dikili Agricultural Based Specialized Greenhouse Organized Industrial Zone Western Anatolia Free Zone Batı Anadolu Serbest Bölge Kurucu ve İşleticisi A.Ş. Dikili Agricultural Greenhouse Specialized Organized Industrial Zone It is 7 km to the Dikili Port, 25 km to the Çandarlı Port and 110 km to the Alsancak Port. It is 62 km to the Aliağa Train Station and 71 km to the Soma Train Station. The closest airport is about 65 km to the project area which is the Koca Seyit airport and it is open to international flights. The project area is about 135 km to İzmir Adnan Menderes Airport. -

Appendix A: Soy Adi Kanunu (The Surname Law)

APPENDIX A: SOY ADı KaNUNU (THE SURNaME LaW) Republic of Turkey, Law 2525, 6.21.1934 I. Every Turk must carry his surname in addition to his proper name. II. The personal name comes first and the surname comes second in speaking, writing, and signing. III. It is forbidden to use surnames that are related to military rank and civil officialdom, to tribes and foreign races and ethnicities, as well as surnames which are not suited to general customs or which are disgusting or ridiculous. IV. The husband, who is the leader of the marital union, has the duty and right to choose the surname. In the case of the annulment of marriage or in cases of divorce, even if a child is under his moth- er’s custody, the child shall take the name that his father has cho- sen or will choose. This right and duty is the wife’s if the husband is dead and his wife is not married to somebody else, or if the husband is under protection because of mental illness or weak- ness, and the marriage is still continuing. If the wife has married after the husband’s death, or if the husband has been taken into protection because of the reasons in the previous article, and the marriage has also declined, this right and duty belongs to the closest male blood relation on the father’s side, and the oldest of these, and in their absence, to the guardian. © The Author(s) 2018 183 M. Türköz, Naming and Nation-building in Turkey, https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-56656-0 184 APPENDIX A: SOY ADI KANUNU (THE SURNAME LAW) V.