Minding the Gaps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sign Language Typology Series

SIGN LANGUAGE TYPOLOGY SERIES The Sign Language Typology Series is dedicated to the comparative study of sign languages around the world. Individual or collective works that systematically explore typological variation across sign languages are the focus of this series, with particular emphasis on undocumented, underdescribed and endangered sign languages. The scope of the series primarily includes cross-linguistic studies of grammatical domains across a larger or smaller sample of sign languages, but also encompasses the study of individual sign languages from a typological perspective and comparison between signed and spoken languages in terms of language modality, as well as theoretical and methodological contributions to sign language typology. Interrogative and Negative Constructions in Sign Languages Edited by Ulrike Zeshan Sign Language Typology Series No. 1 / Interrogative and negative constructions in sign languages / Ulrike Zeshan (ed.) / Nijmegen: Ishara Press 2006. ISBN-10: 90-8656-001-6 ISBN-13: 978-90-8656-001-1 © Ishara Press Stichting DEF Wundtlaan 1 6525XD Nijmegen The Netherlands Fax: +31-24-3521213 email: [email protected] http://ishara.def-intl.org Cover design: Sibaji Panda Printed in the Netherlands First published 2006 Catalogue copy of this book available at Depot van Nederlandse Publicaties, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Den Haag (www.kb.nl/depot) To the deaf pioneers in developing countries who have inspired all my work Contents Preface........................................................................................................10 -

138904 02 Classic.Pdf

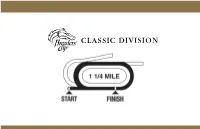

breeders’ cup CLASSIC BREEDERs’ Cup CLASSIC (GR. I) 30th Running Santa Anita Park $5,000,000 Guaranteed FOR THREE-YEAR-OLDS & UPWARD ONE MILE AND ONE-QUARTER Northern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 122 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs.; Southern Hemisphere Three-Year-Olds, 117 lbs.; Older, 126 lbs. All Fillies and Mares allowed 3 lbs. Guaranteed $5 million purse including travel awards, of which 55% of all monies to the owner of the winner, 18% to second, 10% to third, 6% to fourth and 3% to fifth; plus travel awards to starters not based in California. The maximum number of starters for the Breeders’ Cup Classic will be limited to fourteen (14). If more than fourteen (14) horses pre-enter, selection will be determined by a combination of Breeders’ Cup Challenge winners, Graded Stakes Dirt points and the Breeders’ Cup Racing Secretaries and Directors panel. Please refer to the 2013 Breeders’ Cup World Championships Horsemen’s Information Guide (available upon request) for more information. Nominated Horses Breeders’ Cup Racing Office Pre-Entry Fee: 1% of purse Santa Anita Park Entry Fee: 1% of purse 285 W. Huntington Dr. Arcadia, CA 91007 Phone: (859) 514-9422 To Be Run Saturday, November 2, 2013 Fax: (859) 514-9432 Pre-Entries Close Monday, October 21, 2013 E-mail: [email protected] Pre-entries for the Breeders' Cup Classic (G1) Horse Owner Trainer Declaration of War Mrs. John Magnier, Michael Tabor, Derrick Smith & Joseph Allen Aidan P. O'Brien B.c.4 War Front - Tempo West by Rahy - Bred in Kentucky by Joseph Allen Flat Out Preston Stables, LLC William I. -

Thinking Like a Linguist Jordan B

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-18392-6 — Thinking like a Linguist Jordan B. Sandoval, Kristin E. Denham Frontmatter More Information Thinking like a Linguist This is an engaging introduction to the study of language for undergraduate or beginning graduate students, aimed especially at those who would like to continue further linguistic study. It introduces students to analytical thinking about language but goes beyond existing texts to show what it means to think like a scientist about language, through the exploration of data and interactive problem sets. A key feature of this text is its flexibility. With its focus on foundational areas of linguistics and scientific analysis, it can be used in a variety of course types, with instructors using it alongside other information or texts as appropriate for their own courses of study. The text can also serve as a supplementary text in other related fields (speech and hearing sciences, psychology, education, computer science, anthropology, and others) to help learners in these areas better understand how linguists think about and work with language data. No prerequisites are necessary. While each chapter often references content from the others, the three central chapters, on sound, structure, and meaning, may be used in any order. Jordan B. Sandoval is Assistant Professor of Linguistics at Western Washington University in Bellingham, WA. She received her BA in Linguistics from Western Washington University and her PhD from the University of Arizona in 2008. Her research interests include orthographic influence on lexical representations, language and iden- tity, and second language phonological acquisition pedagogy. Kristin E. Denham is Professor of Linguistics at Western Washington University. -

204 Longways Stables 204

204 Longways Stables 204 Empire Maker Pioneerof The Nile AMERICAN Star of Goshen PHAROAH Yankee Gentleman Littleprincessemma N. (USA) Exclusive Rosette Storm Cat chesnut filly 23/03/2018 Giant's Causeway ADESTE FIDELES Mariah's Storm 2011 (USA) Imagine Sadler's Wells 1998 Doff The Derby E.B.F./B.C. Nominated AMERICAN PHAROAH (2012), 9 wins at 2 and 3 years, Breeders' Cup Classic (Gr.1). Stud in 2016. Sire of FOUR WHEEL DRIVE, Breeders' Cup Juvenile Turf Sprint, Gr.2, SWEET MELANIA, Jessamine S., Gr.2, MAVEN, Prix du Bois, Gr.3, CAFE PHAROAH, Hyacinth S., L., HARVEY'S LIL GOIL, Busanda S., ANOTHER MIRACLE, Skidmore S., American Theorem, Monarch of Egypt. 1st dam ADESTE FIDELES, 1 win, pl. 3 times at 3 years in IRE. Own sister to VISCOUNT NELSON and POINT PIPER. Dam of : N., (see above), her 2nd foal. 2nd dam IMAGINE, 4 wins at 2 and 3 years in GB and IRE, Irish 1000 Guineas (Gr.1), Oaks S.(Gr.1), C. L. Weld Park S.(Gr.3), 2nd Rockfel S.(Gr.2), £382,032. Own sister to STRAWBERRY ROAN. Dam of 12 foals of racing age, 9 winners incl. : HORATIO NELSON (c., Danehill), 4 wins at 2 years in FR, IRE & GB, Prix Jean-Luc Lagardère (Gr.1), Futurity S.(Gr.2), Superlative S.(Gr.3), 2nd Dewhurst S.(Gr.1), £284,236. VISCOUNT NELSON (c., Giant's Causeway), 4 wins at 2 to 5 in IRE & UAE, Al Fahidi Fort S.(Gr.2), 2nd Champagne S.(Gr.2), 3rd Irish 2000 Guineas (Gr.1), Eclipse S.(Gr.1), £465,391. -

Minding the Gap : a Rhetorical History of the Achievement

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Minding the gap : a rhetorical history of the achievement gap Laura Elizabeth Jones Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Jones, Laura Elizabeth, "Minding the gap : a rhetorical history of the achievement gap" (2013). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3633. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3633 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. MINDING THE GAP: A RHETORICAL HISTORY OF THE ACHIEVEMENT GAP A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English by Laura Jones B.S., University of Colorado, 1995 M.S., Louisiana State University, 2010 August 2013 To the students of Glen Oaks, Broadmoor, SciAcademy, McDonough 35, and Bard Early College High Schools in Baton Rouge and New Orleans, Louisiana ii Acknowledgements I am happily indebted to more people than I can name, particularly members of the Baton Rouge and New Orleans communities, where countless students, parents, faculty members and school leaders have taught and inspired me since I arrived here in 2000. I am happy to call this complicated and deeply beautiful community my home. -

Minding the Body Interacting Socially Through Embodied Action

Linköping Studies in Science and Technology Dissertation No. 1112 Minding the Body Interacting socially through embodied action by Jessica Lindblom Department of Computer and Information Science Linköpings universitet SE-581 83 Linköping, Sweden Linköping 2007 © Jessica Lindblom 2007 Cover designed by Christine Olsson ISBN 978-91-85831-48-7 ISSN 0345-7524 Printed by UniTryck, Linköping 2007 Abstract This dissertation clarifies the role and relevance of the body in social interaction and cognition from an embodied cognitive science perspective. Theories of embodied cognition have during the past two decades offered a radical shift in explanations of the human mind, from traditional computationalism which considers cognition in terms of internal symbolic representations and computational processes, to emphasizing the way cognition is shaped by the body and its sensorimotor interaction with the surrounding social and material world. This thesis develops a framework for the embodied nature of social interaction and cognition, which is based on an interdisciplinary approach that ranges historically in time and across different disciplines. It includes work in cognitive science, artificial intelligence, phenomenology, ethology, developmental psychology, neuroscience, social psychology, linguistics, communication, and gesture studies. The theoretical framework presents a thorough and integrated understanding that supports and explains the embodied nature of social interaction and cognition. It is argued that embodiment is the part and parcel of social interaction and cognition in the most general and specific ways, in which dynamically embodied actions themselves have meaning and agency. The framework is illustrated by empirical work that provides some detailed observational fieldwork on embodied actions captured in three different episodes of spontaneous social interaction in situ. -

Variation in Form and Function in Jewish English Intonation

Variation in Form and Function in Jewish English Intonation Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Rachel Steindel Burdin ∼6 6 Graduate Program in Linguistics The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: Professor Brian D. Joseph, Advisor Professor Cynthia G. Clopper Professor Donald Winford c Rachel Steindel Burdin, 2016 Abstract Intonation has long been noted as a salient feature of American Jewish English speech (Weinreich, 1956); however, there has not been much systematic study of how, exactly Jewish English intonation is distinct, and to what extent Yiddish has played a role in this distinctness. This dissertation examines the impact of Yiddish on Jewish English intonation in the Jewish community of Dayton, Ohio, and how features of Yiddish intonation are used in Jewish English. 20 participants were interviewed for a production study. The participants were balanced for gender, age, religion (Jewish or not), and language background (whether or not they spoke Yiddish in addition to English). In addition, recordings were made of a local Yiddish club. The production study revealed differences in both the form and function in Jewish English, and that Yiddish was the likely source for that difference. The Yiddish-speaking participants were found to both have distinctive productions of rise-falls, including higher peaks, and a wider pitch range, in their Yiddish, as well as in their English produced during the Yiddish club meetings. The younger Jewish English participants also showed a wider pitch range in some situations during the interviews. -

Lecture 5 Sound Change

An articulatory theory of sound change An articulatory theory of sound change Hypothesis: Most common initial motivation for sound change is the automation of production. Tokens reduced online, are perceived as reduced and represented in the exemplar cluster as reduced. Therefore we expect sound changes to reflect a decrease in gestural magnitude and an increase in gestural overlap. What are some ways to test the articulatory model? The theory makes predictions about what is a possible sound change. These predictions could be tested on a cross-linguistic database. Sound changes that take place in the languages of the world are very similar (Blevins 2004, Bateman 2000, Hajek 1997, Greenberg et al. 1978). We should consider both common and rare changes and try to explain both. Common and rare changes might have different characteristics. Among the properties we could look for are types of phonetic motivation, types of lexical diffusion, gradualness, conditioning environment and resulting segments. Common vs. rare sound change? We need a database that allows us to test hypotheses concerning what types of changes are common and what types are not. A database of sound changes? Most sound changes have occurred in undocumented periods so that we have no record of them. Even in cases with written records, the phonetic interpretation may be unclear. Only a small number of languages have historic records. So any sample of known sound changes would be biased towards those languages. A database of sound changes? Sound changes are known only for some languages of the world: Languages with written histories. Sound changes can be reconstructed by comparing related languages. -

Language Usage and Identity of Somali Males in America Ali Hassan St

St. Cloud State University theRepository at St. Cloud State Culminating Projects in English Department of English 12-2017 "Where Did You Leave the Somali Language?" Language Usage and Identity of Somali Males in America Ali Hassan St. Cloud State University Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/engl_etds Recommended Citation Hassan, Ali, ""Where Did You Leave the Somali Language?" Language Usage and Identity of Somali Males in America" (2017). Culminating Projects in English. 106. https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/engl_etds/106 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at theRepository at St. Cloud State. It has been accepted for inclusion in Culminating Projects in English by an authorized administrator of theRepository at St. Cloud State. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Where did you leave the Somali Language?” Language usage and identity of Somali Males in America by Ali Hassan A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of St. Cloud State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English: Teaching English as a Second Language December, 2017 Thesis Committee: Michael Schwartz, Chairperson Choonkyong Kim Rami Amiri 2 Abstract Research in second language teaching and learning has many aspects to focus on, but this paper will focus on the sociolinguistic issues related to language usage and identity. Language usage is the lens that is used to understand the identity of Somali males in America. Language usage in social contexts gives us the opportunity to learn the multiple identities of Somali males in America. -

Periphrastic Causative Constructions in Mehweb Daria Barylnikova National Research University Higher School of Economics

Chapter 6 Periphrastic causative constructions in Mehweb Daria Barylnikova National Research University Higher School of Economics In Mehweb, periphrastic causatives are formed by a combination of the infinitive of the lexical verb with another verb, originally a caused motion verb. Various tests that Mehweb periphrastic causatives do not qualify as fully grammaticalized. But the constructions are not compositional expressions, either. While a clause usually contains either a morphological or a periphrastic causative marker, there are instances where, in a periphrastic causative construction, the lexical verb itself may carry the causative affix, resulting in only one causative meaning. Keywords: causative, periphrastic causative, double causative, Mehweb, Dargwa, East Caucasian. 1 Introduction The causative construction denotes a complex situation consisting of twocom- ponent events: (1) the event that causes another event to happen; and (2) the result of this causation (Comrie 1989: 165–166; Nedjalkov & Silnitsky 1973; Ku- likov 2001). Here, the first event refers to the action of the causer and the second explicates the effect of the causation on the causee. Causativization is a valency-increasing derivation which is applied to the structure of the clause. In the resulting construction, the causer is the subject and the causee shifts to a non-subject position. The set of semantic roles does not remain the same. Minimally, a new agent is added. With a new argument added, we have to redistribute the grammatical relations taking into account how these participants semantically relate to each other. The general scheme of the causative derivation always implies a participant that is treated as a causer (someone or something that spreads their control over the situation and “pulls Daria Barylnikova. -

The Syntax of Simple and Compound Tenses in Ndebele Joanna Pietraszko*

Proc Ling Soc Amer Volume 1, Article 18:1-15 doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.3765/plsa.v1i0.3716 The Syntax of simple and compound tenses in Ndebele Joanna Pietraszko* Abstract. It is a widely accepted generalization that verbal periphrasis is triggered by in- creased inflectional meaning and a paucity of verbal elements to support its realization. This work examines the limitations on synthetic verbal forms in Ndebele and argues that periphrasis in this language arises via a last-resort grammatical mechanism. The proposed trigger of auxiliary insertion is c-selection – a relation between inflectional categories and verbs. Keywords. verbal periphrasis; default auxiliary; c-selection; Ndebele; Bantu 1. Introduction. This paper focuses on the mechanics of default periphrasis – a phenomenon where a default verb (an auxiliary) appears in a complex inflectional context. I provide an anal- ysis of two types of compound tenses in Ndebele:1 Perfect and Prospective tenses, arguing that periphrastic expressions in those tenses are triggered by c-selectional features on T heads. The type of verbal periphrasis we find in Ndebele is known as the overflow pattern of auxiliary use (Bjorkman, 2011), and is illustrated in (1),2 where Present Perfect and Simple Future are synthetic (there is no auxiliary), but Future Perfect is periphrastic (1-c). (1) Default periphrasis in Ndebele: a. U- ∅- dl -ile Present Perfect/Recent Past (synthetic) 2sg- PST- eat -FS.PST ‘You have eaten/you ate recently’. b. U- za- dl -a Simple Future (synthetic) 2sg- FUT- eat -FS ‘You will eat’. c. U- za- be u- ∅- dl -ile Future Perfect (periphrastic) 2sg- FUT- aux 2sg- PST- eat -FS.PST ‘You will have eaten’. -

19 Chapter 2. Cyclic and Noncyclic Phonological Effects a Proper

Chapter 2. Cyclic and noncyclic phonological effects A proper theory of the phonology-morphology interface must account for apparent cyclic phonological effects as well as noncyclic phonological effects. Cyclic phonological effects are those in which a morphological subconstituent of a word seems to be an exclusive domain for some phonological rule or constraint. In this chapter, I show how Sign-Based Morphology can handle noncyclic as well as cyclic phonological effects. Furthermore, Sign-Based Morphology, unlike other theories of the phonology-morphology interface, relates the cyclic-noncyclic contrast to independently motivatable morphological structures. 2.1 Turkish prosodic minimality The example in this section is a disyllabic minimal size condition that some speakers of Standard Istanbul Turkish impose on affixed forms (Itô and Hankamer 1989, Inkelas and Orgun 1995). The examples in (28b) show that affixed monosyllabic forms are ungrammatical for these speakers (unaffixed monosyllabic forms are accepted (28a), as are semantically similar polysyllabic affixed forms (29b). (28) a) GRÛ ‘musical note C’ b) *GRÛ-P ‘C-1sg.poss’ MH ‘eat’ *MH-Q ‘eat-pass’ (29) a) VRO- ‘musical note G’ b) VRO--\P ‘G-1sg.poss’ N$]$Û ‘accident’ N$]$Û-P ‘accident-1sg.poss’ MXW ‘swallow’ MXW-XO ‘swallow-pass’ WHN-PHO-H ‘kick’ WHN-PHO-H-Q ‘kick-pass’ What happens when more suffixes are added to the forms in (28b) to bring the total size to two syllables? It turns out that nominal forms with additional affixes are still ungrammatical regardless of the total size, as shown by the data in (30). (30) *GRÛ-P ‘C-1sg.poss’ *GRÛ-P-X ‘C-1sg.poss’ *UHÛ-Q ‘D-2sg.poss’ *UHÛ-Q-GHQ ‘D-2sg.poss-abl’ *I$Û-P ‘F-1sg.poss’ *I$Û-P-V$ ‘F-1sg.poss-cond’ These forms suggest that the disyllabic minimal size condition is enforced cyclically.