Moneyandpoliticsreportfinalweb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LS-012-2020 (Extension of Virtual Council, Board and Committee

REPORT TO COUNCIL REPORT NUMBER: LS-012-2020 DEPARTMENT: LEGISLATIVE SERVICES – By-law MEETING DATE: August 10, 2020 SUBJECT: Extension of Virtual Council, Board and Committee Meetings RECOMMENDATION: Be It Resolved, that Council of the Township of Clearview hereby support the recommendation from the Medical Officer of Health for Simcoe Muskoka Health Unit and continue to facilitate all council, board and committee meetings electronically. BACKGROUND: On July 20, 2020, Dr. Gardner issued a letter to state gatherings of up to 50 people were permitted in the Province of Ontario, however, the Simcoe Muskoka Health Unit continues its advice to encourage municipal councils to hold electronic meetings rather than in person meetings of any nature. COMMENTS AND ANALYSIS: The health and safety of council, volunteers, members of the public and staff must be taken into consideration when planning any in person interactions. This includes public gatherings of council and board/committee meetings. To date, many municipalities have agreed to continue electronic meetings well into the Fall. This includes the City of Barrie, Oro-medonte, Tiny, Innisfil, Penetanguishene, Collingwood and Midland. The Township of Springwater will be holding electronic meetings for the balance of 2020. There is no doubt COVID 19 pandemic has changed the way municipal government functions. It has been difficult to adjust to the changes, and the Township has had to take a different approach to how we continue operations and services. This includes how council, board and committee meetings are conducted during the pandemic. Staff hope these changes will be temporary in nature and activities can Page 1 of 3 return to “normal” soon upon advice from the appropriate medical officers of health. -

Simcoe Alternative Secondary School

Simcoe Alternative Secondary School About Us Main Office: The Alternative Education program offers students who are experiencing difficulty in the regular school 4 -229 Mapleview Drive E. system the opportunity to earn credits in a smaller more intimate setting, at one of our ten alternate Barrie, ON L4N 0W5 locations in Simcoe County. 705-728-7601 Course work may be a combination of regular classes, independent courses, dual credits, eLearning and credit recovery. Website Candidates may be referred by a high school or may self-refer. Once the referral is made to our main office, www.scdsb.on.ca the student will be contacted by a teacher to arrange for an appointment where the student and teacher will determine suitability of this program. Alternative School candidates must be able to: Work independently Principal Have the ability to self-regulate and collaborate with others Laura Lee Millard-Smith Exhibit a willingness to participate in the school Working towards workplace or college pathway Demonstrate literacy skills at grade 7 or higher competency Campuses Program Highlights Alliston Students will receive assistance developing an Educational Pathway Plan which may include a transition South Barrie plan to: Barrie Young Parents High school or Adult Learning Centre for completion of their OSSD North Barrie The workplace Bradford Apprenticeship Collingwood College Essa Midland What to expect once enrolled Innisfil Upon admission into the Alternative School, students will be given the opportunity to build an individualized Orillia learner profile, to assist them in their growth as a student and in the development of his/her educational and career life path. -

OLG Picks Operator for Casinos in Innisfil, Casino Rama

OLG picks operator for casinos in Innisfil, Casino Rama Gateway will also operate a future site still to be chosen between Collingwood or Wasaga Beach NEWS MAR 15, 2018 BY IAN ADAMS WASAGA SUN People try their hand at playing slot machines inside an Ontario casino. - Ontario Lottery and Gaming Corporation/Submitted The Ontario Lottery and Gaming Corporation has picked Burnaby, B.C.-based Gateway Casinos and Entertainment to operate gaming facilities in central Ontario. The company will take over operations of Georgian Downs and Casino Rama this summer, while also starting the process of determining the location of a gaming facility in either Collingwood or Wasaga Beach. Gateway’s Ontario spokesperson Rob Mitchell said the company’s current focus will be on the transition for employees at Georgian Downs and Casino Rama, before it can establish a timeline for what might happen in Collingwood or Wasaga Beach. He added there is still “considerable study before we land on a location and get our ducks in a row to do an analysis” of the Collingwood and Wasaga Beach markets. Related Content Georgian Downs, casino merger announcement coming in spring Beachfront added to potential sites for Wasaga Beach casino Casino in Collingwood may not be a sure bet Mitchell said the company will be speaking to both municipalities about what land is available, as well as examining sites that have already been identified as potential locations. Wasaga Beach has identified five potential sites for a gaming facility. Collingwood, while signaling its interest as a willing host, has not identified any particular properties. -

The Regional Municipality of York at Its Meeting on September 24, 2009

Clause No. 5 in Report No. 6 of the Planning and Economic Development Committee was adopted, without amendment, by the Council of The Regional Municipality of York at its meeting on September 24, 2009. 5 PLACES TO GROW - SIMCOE AREA: A STRATEGIC VISION FOR GROWTH - ENVIRONMENTAL BILL OF RIGHTS REGISTRY POSTING 010-6860 REGIONAL COMMENTS The Planning and Economic Development Committee recommends adoption of the recommendations contained in the following report dated July 29, 2009, from the Commissioner of Planning and Development Services with the following additional Recommendation No. 10: 10. The Commissioner of Planning and Development Services respond further to the Ministry of Energy and Infrastructure regarding the Environmental Bill of Rights Registry Posting 010-6860 to specifically address the Ontario Municipal Board resolution regarding Official Plan Amendment No. 15 in the Town of Bradford West Gwillimbury, and report back to Committee. 1. RECOMMENDATIONS It is recommended that: 1. Council endorse staff comments made in response to the Environmental Bill of Rights Registry posting 010-6860 on Places to Grow – Simcoe Area: A Strategic Vision for Growth, June 2009. 2. The Province implement the Growth Plan equitably and ensure that all upper- and lower-tier municipalities in the Greater Golden Horseshoe are subject to the same policies and regulations as contained in the Growth Plan and the Places to Grow Act. 3. The Province assess the impact on the GTA regions including York Region, resulting from the two strategic employment area provincial designations in Bradford West Gwillimbury and Innisfil. Council requests that the Province undertake this assessment and circulate to York Region and the other GTA regions prior to the approval and finalization of the Simcoe area-specific amendment to the Growth Plan. -

SMRCP Aboriginal Cancer Plan

1 This plan was developed in collaboration with our community partners. Special thanks to the Aboriginal Health Circle for their valuable input and ongoing partnership which is essential to the success of this work. 2 Aboriginal Communities in the North Simcoe Muskoka Region Regional Index First Nations Communities 11. Beausoleil First Nation 24. Chippewas of Rama First Nation 74. Moose Deer Point First Nation 121. Wahta Mohawks Metis Nation of Ontario Community Councils 5. Georgian Bay Métis Council 13. Moon River Métis Council 3 The First Nation, Métis and Inuit (FNMI) population of the North Simcoe Muskoka (NSM) region is approximately 20,000, accounting for approximately 6% of Ontario’s Indigenous inhabitants. The region is home to 4 First Nations communities and 2 Métis Community Councils: Moose Deer Point First Nation, Beausoleil First Nation and Chippewas of Rama (served by the Union of Ontario Indians), Wahta Mohawks (served by the Association of Iroquois and Allied Indians), the Georgian Bay Métis Council, and Moon River Métis Council. It should be noted here that Midland and Innisfil consecutively have the 1st and 2nd largest Métis populations in Ontario. In addition to these communities, NSM is home to a large urban Aboriginal population. There are now more Aboriginal people living in urban centers than there are living in Aboriginal territories, communities on reserves and Métis settlements. It is estimated that 65% of the Indigenous population of Simcoe Muskoka constitute a permanent presence throughout the region. This percentage of the Indigenous community is primarily serviced by Native Women’s Groups, Native Friendship Centre's and additional community based organizations listed on page 7 of this document. -

Cost Pre-Requisite Barrie Collingwood Innisfil Midland Orillia

Lifesaving Society Safeguard LSS Bronze Medallion YMCA Assistant Pre-Bronze LSS Bronze Star LSS Bronze Cross/SFA/CPR C LSS National Lifeguard Standard First Aid & CPR C YMCA Swim Instructor Course EFA/CPR B Swim Instructor Member: $180 + HST Member: $100 + HST Non-Member: $270 + HST Non-Member: $125 + HST Member: $15 + HST Member: $20 + HST Member: $60 + HST Member: $156 + HST Member: $156 + HST Member: $250 + HST Member: $40 +HST Cost Non-Member: $40 + HST Non-Member: $45 + HST Non-Member: $105 + HST Non-Member: $195 + HST Non-Member: $195 + HST Non-Member: $270 + HST Non-Member: $68 +HST Recert-Member: $75 + HST Recert-Member: $85 + HST Non-Member: $100 + HST Non-Member: $105 + HST 12 years of age 12 years of age 14 years of age 12 years of age 14 years of age 16 years of age 16 years of age Preferred: Star 7 and/or Preferred: Star 7 and/or 13 years of age OR Bronze Star 12 years of age preferred Bronze Cross or Pre-Requisite Preffered: Star 7 Bronze Med & EFA/B Cross & SFA/C Bronze Cross & SFA/C completion of Safeguard course completion of Safeguard course Star 7 March 8, 9, 10, 22, 23, 24 Feb 9 & 10 Friday's 4:00PM-8:00PM June 15 & 16 Please email Jan 11 - March 8 March 11-15 March 11-15 Saturday's 9:00AM-9:00PM Recert: [email protected] for Barrie Friday's 4:00PM-5:00PM Monday - Friday Monday-Friday Sunday's 8:00AM-4:00PM Feb 10 & June 16 details 10:00AM-3:00PM 10:00AM-3:00PM Recert: 8:30AM-4:30PM March 24 12:00PM-4:00PM 1)Sept 11-Dec 3 July 6-Aug 24 OR May 10 - 12 March 19 - June 4 March 18 - June 4 March 18 - June 3 April -

The Orbit: Innisfil Rural Re-Imagined

The Orbit: Innisfil RURAL RE-IMAGINED + Vision I Embracing Innovation and the Future II A Design Like No Other III Canada’s Most Desirable Community IV Our Small-Town Character and Heritage V A Complete Community VI Getting Around VII A Home for Everyone VIII Summary IX Innisfil 2 The Orbit 3 Contents The Orbit is our vision for a complete, cutting-edge community where our small town and rural Welcome to the ORBIT lifestyles are enhanced by the benefits and attributes of urban living. Vision I The vision recognizes Innisfil for its unique city building and agriculture, open spaces, access to trails The Orbit means great architecture. It’s context and character; proposes a new & waterfront and walkability, which are all where architecture and design push the urban fabric that will push the limits of architectural thinking. part of this rural reimagination. envelope towards an artful yet sustainable possibility; igniting interested and inspiring city of the future. The Orbit is a vision for a Next Generation citizens today and tomorrow to be part of As an extension this new place. At the heart of it we imagine Community located 60 km North of The Orbit is a clean slate to reimagine how a cohesive center for Innisfil, currently a Canada’s largest city, Toronto. The planned in the tradition of a community of tomorrow is built today. municipality of clustered hamlets, that will project has the capacity to absorb over the garden city, the Mobility, transit links, innovative streets gravitate and grow around a new regional 40 million square feet (4 million square and infrastructure, streetscapes, social transit link and cultural center slated to be meters) of newly built modern community. -

Simcoe County District School Board French Immersion (FI)

Simcoe County District School Board French Immersion (FI) Program Designated School Sites and Feeder Schools 2018 – 2019 Please note: French Immersion will be offered in Grades 1 - 6 only in the 2018-2019 school year. Some feeder schools will have more than one designated FI site because students feed to different secondary schools. French Immersion will begin in SCDSB secondary schools in September 2021. FI School Sites Designated Feeder Schools FI School Sites Designated Feeder Schools Cameron Street PS (Gr. 1-4) Admiral Collingwood ES Hillcrest PS (Gr. 1-4, map 5) Andrew Hunter ES 575 Cameron St. Collingwood, ON Cameron Street PS 184 Toronto Street Barrie, ON Emma King ES 705-445-2902 to Connaught PS 705-728-5246 to Hillcrest PS Admiral Collingwood ES Mountain View ES Portage View PS (Gr. 5-6) Portage View PS (Gr. 5-6) Nottawa ES 124 Letitia Street Barrie, ON West Bayfield ES 15 Dey Dr. Collingwood, ON Nottawasaga & Creemore PS 705-728-1302 to 705-445-0811 to Eastview SS (map 5) Collingwood CI 421 Grove St. E. Barrie, ON 6 Cameron St. Collingwood, ON 705-728-1321 705-445-3161 Ernest Cumberland ES Adjala Central PS Hillcrest PS (Gr. 1-4, map 5) Allandale Heights PS (Gr. 1-4) Alliston Union PS to Assikinack PS 160 Eighth Street Alliston, ON Baxter Central PS (map 4) Portage View PS (Gr. 5-6) to 705-435-0676 to Boyne River PS Innisdale SS (map 5) Alliston Union PS (Gr. 5-6) Cookstown Central PS (map 1) 95 Little Ave. Barrie, ON 211 Church St. -

Zoning By-Law 080-13

TOWN OF INNISFIL COMPREHENSIVE ZONING BY-LAW 080-13 (Council Adopted) July 10, 2013 (contains amendments up to end of April, 2021) Note that map schedules are in the process of being updated – for information relative to a specific property please contact the Town of Innisfil Page i Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS PREAMBLE ............................................................................................................................. 1 A. Introduction B. Purpose of this By-law C. Authority to prepare this By-law D. Structure of this By-law E. Use of the Holding Symbol (“(H)”) F. Use of the Waterfront Symbol (“-W”) G. How to Check Zoning and Identify Applicable Regulations for a Property H. Purposes of Zones I. Subsequent Zoning By-law Amendments J. Minor Variances K. About Legal Non-Conforming Uses L. About Legal Non-Complying Buildings and Structures M. Accessory Uses, Buildings and Structures (Garages, Boathouses, Accessory Dwellings, etc.) 1.0 INTERPRETATION AND ADMINISTRATION ......................................................... 14 2.0 DEFINITIONS .......................................................................................................... 20 3.0 GENERAL PROVISIONS ........................................................................................ 50 3.1 CONTENTS ............................................................................................................. 50 3.2 APPLICATION ........................................................................................................ -

January 2021

INNISFIL PUBLIC LIBRARY BOARD MEETING AGENDA 2a.01.01 Monday, January 18, 2021 – 7:00 p.m. Via Zoom 1. Call to Order 2. Approval of Agenda (copy & motion) [Motion #2021. – THAT the agenda of the January 18, 2021 meeting be approved as presented.] 3. Declaration of Interest None at time of agenda creation 4. Delegations to the Board None at time of agenda creation 5. Consent Agenda (motion) a) Approval of Previous Minutes (copy) Recommendation THAT the minutes of the December 14, 2020 Board Meeting be approved as presented. b) Correspondence (copy) Recommendation THAT Correspondence Item 5b.01.01 to 5b.05.01 for December 2020 be received. c) CEO Reports (copy) Recommendation THAT the CEO Report 5c.01.01 for December be received. d) Financial Reports (copy) Recommendation THAT the Financial Reports 5d.01.01 to 5d.01.03 for December 2020 be received. e) Policies Recommendation None at time of agenda creation Consent Recommendation [Motion #2021. – THAT the consent agenda items 5 a) to 5 e), and the recommendations contained therein be approved as presented.] 6. Business Arising a) Board Budget Committee Report (motion) [Motion #2021.XX THAT the 2021 Capital Budget in the amount of $124,053 as approved by Council Resolution #2020.12.09-CR-02 on December 9, 2020 be approved; And FURTHER, THAT the 2022 Capital Budget in the amount of $132,955 as approved by Council Resolution #2020.12.09-CR-02 on December 9, 2020 be approved, subject to the Town’s current Multi-Year Budget Policy.] [Motion 2021.XX THAT the 2021 Operating Budget in the amount of $3,395,610, including a 1% COLA for Library Staff as per the Library’s 2021 Salary Plan, as approved by Council Resolution #2020.12.09-CR-02 on December 9, 2020 be approved; And FURTHER, THAT the 2022 Operating Budget in the amount of $3,477,315, including a 1% COLA for Library Staff as per the Library’s 2022 Salary Plan, as approved by Council Resolution #2020.12.09-CR-02 on December 9, 2020 be approved, subject to the Town’s current Multi-Year Budget Policy.] 7. -

Appendix E - Public Consultation - Study Notices

Town of Innisfil APPENDIX E - PUBLIC CONSULTATION - STUDY NOTICES E-1 Stakeholder Register Agencies and Ministries (Excluding Indigenous Peoples) Agency/Ministry Division Civic Address City Province Postal Code Salutation First Name Last Name Position Telephone No. Email Address Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks (MECP) Central Region [email protected] Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks (MECP) Central Region Ms. EA/Planning Coordinator Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks (MECP) Environmental Approvals Branch [email protected] Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport Heritage Program Unit - Programs and Services Branch 401 Bay Street, Suite 1700 Toronto ON M7A 0A7 Ms. Karla Barboza Team Lead - Heritage 416-314-7120 [email protected] Ministry of Tourism, Culture and Sport Ministries of Citizenship, Immigration, Tourism, Culture and4275 Sport King St, 2nd Floor Kitchener ON N2P 2E9 Mr. Chris Stack Manager, West Region 519-650-3421 [email protected] Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (MNRF) Midhurst District 1 Stone Rd W Guelph ON N1G 4Y2 Ms. Dan Thompson District Manager (519) 826-4931 [email protected] Other Stakeholders Agency/Ministry Division Civic Address City Province Postal Code Salutation First Name Last Name Position Telephone No. Email Address Lake Simcoe Region Conservation Authority Frank Pinto [email protected] South Simcoe Police North Division [email protected] Innisfil Fire Services [email protected] Town of Innisfil Ward 2 Councillor Bill Van Berkel [email protected] Town of Innisfil Mayor Lynn Dollin [email protected] Town of Innisfil Deputy Mayor Daniel Davidson [email protected] County of Simcoe Administration Centre 1110 Highway 26 Midhurst ON L9X 1N6 Mark Aiken CAO [email protected] County of Simcoe George Cornell Simcoe County Warden [email protected] First Nations Agency/Ministry Division Civic Address City Province Postal Code Salutation First Name Last Name Position Telephone No. -

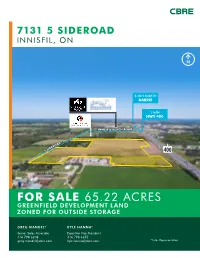

7131 5 Sideroad Innisfil, On

7131 5 SIDEROAD INNISFIL, ON N 5 MIN NORTH BARRIE 1 MIN HWY 400 INNISFIL BEACH ROAD 5 SIDEROAD FOR SALE 65.22 ACRES GREENFIELD DEVELOPMENT LAND ZONED FOR OUTSIDE STORAGE GREG MANDEL* KYLE HANNA* Senior Sales Associate Executive Vice President 416 798 6208 416 798 6255 [email protected] [email protected] *Sales Representative 1 7131 5 SIDEROAD 7131 5 SIDEROAD 20 MIN SOUTH BRADFORD 5 SIDEROAD 5 MIN NORTH BARRIE N HIGHLIGHTS PROPERTY OVERVIEW Major frontage onto Hwy 400 Development charges $27.47 PSF Quick access to Hwy 400 at Innisfil Beach Road Zoning permits many uses including outside storage GROSS ACREAGE: 65.22 ACRES TAXES (2020): $2,270.86 Partial municipal services at lot line Major developer owned parcels nearby ASKING PRICE: $13,750,000 ZONING: INDUSTRIAL BUSINESS PARK (IBP) Future interchange at Hwy 400 & 6th Line Located within Innisfil Heights Strategic Settlement Employment Area Road widening of Hwy 400 underway Provincially designated “Places to Grow” area Road widening of Innisfil Beach Road underway 2 3 Transportation Corridor GTA and Simcoe County Lake Simcoe Regional Springwater 400 Airport Clearview Oro-Medonte Allendale Waterfront Barrie Lake Simcoe CFB Barrie South Borden Stroud Innisfil Beach Rd. Essa ★ County of 6th Line Dufferin (future) TransportationChurchill Corridor GTA andInnisfil Simcoe County 7131 5 SIDEROAD Strategic Settlement 89 7131 5 SIDEROAD Lake Simcoe Adjala- Regional 400 Airport INNISFIL HEIGHTS STRATEGICEmployment EMPLOYMENT Area AREA Tosorontio BradfordSpringwater Clearview West Oro-Medonte Gwillimbury T R A N S I T New Allendale Waterfront BARRIE Tecumseth Barrie Lake Simcoe & HIGHWAY CFB Barrie BradfordSouth Borden ACCESSIBILITY Stroud Innisfil Beach Rd.