University Musical Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

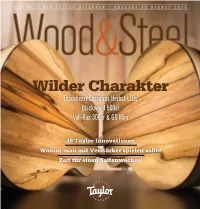

Wilder Charakter Blackheart Sassafras Herbst-Ltds Blackwood 500Er Voll-Koa 300Er & GS Mini

Wilder Charakter Blackheart Sassafras Herbst-LTDs Blackwood 500er Voll-Koa 300er & GS Mini 40 Taylor-Innovationen Warum man mit Verstärker spielen sollte Zeit für einen Saitenwechsel 2 www.taylorguitars.com | Sommerausgabe]. Ich war von 1984 12 hatte ich mal Klavierunterricht gehabt, sofort, dass sich die Basswiedergabe AUSGABE 80 herbst 2014 bis 1988 der Fahrer von Prince. Auch aber als ich die Mädchen entdeckte, war der A- und E-Saite massiv verschlechtert Leserbriefe auf der Purple Rain-Tour war ich dabei. es mit meiner angehenden Musikkarriere hatte. Ich war niedergeschmettert. Die Mir wurde ein umgebauter schwarzer am Ende. Ein langjähriger Freund vom Gitarre klang nicht mehr wie eine Taylor. > IN DIESER AUSGABE < Besuchen Sie uns auf Facebook. Abonnieren Sie uns auf YouTube. Folgen Sie uns auf Twitter: @taylorguitars Transporter zugeteilt, um Prince zu Hot Licks Guitar Shop verkauft Taylor- Außerdem war nicht mehr viel vom Steg den klanglichen Verbesserungen, von fahren. Als ich mir den Wagen ansah, Gitarren. Er war überzeugt davon, dass übrig, und die Justierung hatte einen den strahlenden Höhen bis zu den stieß ich auf einen Gitarrenkoffer. Ich ich noch was lernen kann. Also kaufte dämpfenden Effekt auf das Sustain der tiefen, artikulierten Bässen, rockt es spiele selbst Gitarre, weshalb ich ich eine 518e, und ich liebe ihren Klang. tiefen E-Saite. Es fehlten die starken mit dieser Gitarre viel besser, und ich neugierig war. Ich sah an der Seite Inzwischen sieht mein Zuhause aus wie Bass-Schwingungen, die ich zu hören muss sie nicht missbrauchen, um die den Taylor-Schriftzug, aber ich muss eine Taylor-Ausstellung. Jedes Modell ist und fühlen gewöhnt war. -

Hits Der 90Er

Hits der 90er Absolute Beginner – Liebeslied Die Ärzte - Männer sind Schweine Culcha Candela –Hamma Extrarbeit - Flieger, Grüß Mir Die Sonne Die Fantastischen Vier – MfG Glashaus – Wenn das Liebe ist Hape Kerkeling – Hurz! Hape Kerkerling – Das ganze Leben ist ein Quiz Mo-Do - Eins Zwei Polizei Lucilectric – Mädchen Die Toten Hosen - Alles Aus Liebe Die Prinzen – Alles nur geklaut Oli. P. - Flugzeuge im Bauch Echt - Alles wird sich ändern Echt - Du trägst keine Liebe in dir Xavier Naidoo – Sie sieht mich nicht Matthias Reim – Verdammt ich lieb Dich Matthias Reim – Ich hab’ geträumt von dir Rammstein – Engel Sabrina Setlur – Du liebst mich nicht Helge Schneider – Katzenklo Steuersong Wildecker Herzbuben – Herzilein Hits ab 2000 Andrea Berg – Du hast mich 1000 Mal belogen Ayman - Mein Stern Buddy – Ab in den Süden Ben - Herz aus Glas Die Ärzte – Manchmal haben Frauen… Yvonne Catterfeld - Für Dich Echt - Junimond Die 3. Generation – Leb! DJ Ötzi - Ein Stern Herbert Grönemeyer – Mensch Juli - Perfekte Welle Laura Schneider – Immer wieder Nena – Wunder geschehen Xavier Naidoo - Wo willst du hin? Rammstein - Sonne Thomas D – Liebesbrief Tokio Hotel – Durch den Monsun Samajona – So schwer Silbermond – Symphonie Söhne Mannheims – Geh davon aus Sportfreunde Stiller – 54, 74, 90, 2006 Kinderlieder Biene Maja Blümchen - Boomerang Blümchen – Heut ist mein Tag Brüderchen, komm tanz mit mir Der, die, das (Sesamstraßenlied) Dolls United - Eine Insel mit 2 Bergen Grauzone – Eisbär Kitty & Knut – Knut der kleine Eisbär Paulchen Panter – Wer hat an der Uhr gedreht Stefan Raab – Hier kommt die Maus Radiopilot – Monster Schnappi, das kleine Krokodil Schnappi - Ein Lama in Yokohama Grün, grün, grün Vater Abraham - Schlumpflied 2 Hits der 90er Absolute Beginner – Liebeslied Refrain: Ihr wollt ein Liebeslied, ihr kriegt ein Liebeslied, ein Lied, das ihr liebt Das ist Liebe auf den ersten Blick Nicht mal Drum' n Bass hält jetzt mit deinem Herzen Schritt. -

Wahrheit Aus Morgentrã¤Umen

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Prose Nonfiction Nonfiction 1824 Wahrheit aus Morgenträumen Friederike Brun Description These works within the Sophie Digital Library are part of a collection of Prose Nonfiction written by German- speaking women. Within this generic category may be found longer works, often of book length, such as biographies, travel reports, memoirs, books of historical, scientific or et chnical writing, etc. Essays, on the other hand, will be nonfiction of shorter length. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sophnf_nonfict Part of the German Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Brun, Friederike, "Wahrheit aus Morgenträumen" (1824). Prose Nonfiction. 55. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sophnf_nonfict/55 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Nonfiction at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Prose Nonfiction by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. WAHRHEIT AUS MORGENTRÄUMEN und IDAS ÄSTHETISCHE ENTWICKELUNG von Friederike Brun, geb. Münter. Süßer Wehmuth Gefährtin Erinn'rung! Wenn jene die Wimper sinnend senkt Hebst du deinen Schleier und lächelst Mit rückwärts gewandtem Gesicht. Salis. Aarau, 1824 bei Heinrich Remigius Sauerländer. Editor's Introduction The original for this work is located in the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin--Preussischer Kulturbesitz. All spelling in this electronic version reproduces that of the original text. A number of divergencies from modern German conventions occur in this work. For example, some words which generally would be spelled with a k, in this manuscript are spelled with ck: Schauckeln, Eckel, etc. Many verbs of French origin which now would appear with the ending ieren appear without the e: existiren, dramatisiren, etc. -

Surfology. Oder Bretter, Die Die Welt Bedeuten (PDF)

Feature Hörspiel Radiokunst Freistil Surfology Oder Bretter, die die Welt bedeuten Von Juliane Stadelmann Produktion: NDR 2020 Redaktion Dlf: Klaus Pilger Sendung: Sonntag, 28.02.2021, 20:05-21:00 Uhr Regie: Eva Solloch Es sprachen: Mohamed Achour, Sonja Beißwenger, Sebastian Jakob Doppelbauer, Torben Kessler, Amelle Schwerk, Hajo Tuschy und die Autorin Musik: Lukas Raabe Technische Realisation: Markus Freund und Corinna Kammerer Urheberrechtlicher Hinweis Dieses Manuskript ist urheberrechtlich geschützt und darf vom Empfänger ausschließlich zu rein privaten Zwecken genutzt werden. Die Vervielfältigung, Verbreitung oder sonstige Nutzung, die über den in §§ 44a bis 63a Urheberrechtsgesetz geregelten Umfang hinausgeht, ist unzulässig. © Juliane: Ich stehe auf der Düne wie Napoleon. Es ist früh am Morgen irgendwo an der französische Atlantikküste. Es ist gerade hell geworden und ich schaue konzentriert aufs Meer als würde ich einen Angriff erwarten. 4 Fuß bei 10 Sekunden, leichter offshore, Mid-Tide... Das sind die Daten aus dem Netz, frisch von der Messboje. Von hier oben sehe ich, wie der ablandige Wind den Wellen ins Gesicht weht, die Gischt sprüht wie eine feine Mähne von den Wellenkämmen Richtung Horizont, wenn sie brechen. Es ist die 3. Stunde nach Tiefstand. Bald wird das Wasser zu hoch über der Sandbank stehen. Der Wind wird drehen. Ich bin mit meinen Füßen tief in den Sand der Düne gesunken. Ich gebe mir einen Ruck, löse mich aus meinem Sandsockel und gehe zurück Richtung Zelt, um mich fertig zu machen. Sprecher Ansage: Surfology – oder Bretter, die die Welt bedeuten Ein Feature über das Wellenreiten von Juliane Stadelmann Geräusch vom Waxen des Brettes. Juliane: Kitzelt dieses Geräusch angenehm im Ohr? Kribbelt es jetzt in der Magengrube? Kam da etwa ein Seufzer über die Lippen? Wenn ja, dann gehört ihr vielleicht zu den knapp 2,2 Millionen Menschen in Deutschland, die 2019 nach eigenen Angaben „ab und zu“ surfen. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 I

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following'explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Bachelorarbeit Absolut Final.Pdf

BACHELORARBEIT Frau Sarah Najar Von unter dem Meer hoch zu den schwebenden Lichtern: Die Suche nach Liebe in Walt Disneys Klassikern 2017/18 Fakultät: Medien BACHELORARBEIT Von unter dem Meer hoch zu den schwebenden Lichtern: Die Suche nach Liebe in Walt Disneys Klassikern Autor/in: Frau Sarah Najar Studiengang: Angewandte Medien/ Media Acting Seminargruppe: AM14wM5-B Erstprüfer: Prof. Peter Gottschalk Zweitprüfer: Frau Rika Fleck, M.Sc. Einreichung: Barnstorf, 8. Januar 2018 Faculty of Media BACHELOR THESIS From under the sea up to the floating lights: The quest for love in Walt Disney’s Classics author: Ms. Sarah Najar course of studies: Applied Media/ Media Acting seminar group: AM14wM5-B first examiner: Prof. Peter Gottschalk second examiner: Ms. Rika Fleck, M.Sc. submission: Barnstorf, 8 January 2018 Bibliografische Angaben Najar, Sarah Von unter dem Meer hoch zu den schwebenden Lichtern: Die Suche nach Liebe in Walt Disneys Klassikern From under the sea up to the floating lights: The quest for love in Walt Disney’s Classics 96 Seiten, Hochschule Mittweida, University of Applied Sciences, Fakultät Medien, Bachelorarbeit, 2017/18 Abstract Die vorliegende Arbeit fokussiert sich auf die Liebe als finale Erkenntnis der Heldenreise in Disneyfilmen und untersucht die dramaturgischen Etappen, die die Protagonisten auf ihrer Suche nach Erkenntnis durchlaufen. Dies geschieht durch eine Analyse und Inter- pretation vierer Disneyfilme: Cinderella (1950), Arielle – Die kleine Meerjungfrau (1989), Die Schöne und das Biest (1991) und Rapunzel – Neu verföhnt (2010). Es soll heraus- gestellt werden, inwiefern die Liebe Einfluss auf die Handlungen der Charaktere nimmt und in welcher Form dieser durch Walt Disney Pictures dargestellt wird. -

Musik Ist Uns Was Wert. Musik

02-2015 Das Magazin der GEMA Das Magazin Musik ist uns was wert. Alle Preisträger, alle Nominierten. Der Preis für das Lebenswerk geht an den Komponisten Verleihung desHelmut Lachenmann Deutschen Musikautorenpreises Mitglieder- versammlung 2015 GEMA Forum Pflichtmitteilungen Wahl des Aufsichtsrats Start des exklusiven sowie der Delegierten Mitglieder-Portals für U. a.: Zahlungs- und der angeschlossenen den Austausch und Vorauszahlungsplan und außerordentlichen das Vernetzen unter sowie Zahlungstermin für Mitglieder Musikschaffenden Zuschlagsverrechnungen zum 1. Juli 2015 2015 editorial Liebe Leserinnen und Leser, 2014 war ertragsmäßig das beste Jahr in der Geschichte der GEMA. Wir konnten an die Rechteinhaber mehr als 755 Millionen Euro ausschütten, womit das Vorjahr noch einmal deutlich übertroffen wurde. Nicht zuletzt die wachsende wirtschaftliche Bedeutung der Onlinelizenzierung hat zu diesem positiven Ergebnis beigetragen – mit rund 45 Millionen Euro erwirtschaftete die GEMA 2014 ein Rekordergebnis im Bereich Online. Aber auch mit dieser Ertragssteigerung sind wir bei Weitem noch nicht dort, wo wir hinkommen wollen und sollten – bei den Urhebern kommt nach wie vor viel zu wenig von den stetig steigenden Onlineumsätzen an. Die wichtigsten Zahlen des Geschäftsjahres 2014 finden Sie auf der Seite 45. Dieses herausragende Ergebnis war auch Thema auf unserer Mitgliederver- sammlung Anfang Mai in München. Turnusmäßig wurden dort der Aufsichtsrat und weitere Gremien sowie die Delegierten der angeschlossenen und außer- ordentlichen Mitglieder neu gewählt. Zudem beschloss die Versammlung unter anderem die Weiterentwicklung des Verteilungsplans für den Nutzungsbereich Online sowie dessen Entfristung. Einen ausführlichen Bericht über die Mitglie- Foto: Florian Jaenicke Florian Foto: derversammlung sowie eine Vorstellung des neu gewählten Aufsichtsrats und Dr. Harald Heker, der Delegierten unserer drei Kurien in der Amtsperiode 2015–2018 finden Sie auf Vorstandsvorsitzender der GEMA Seite 22 bzw. -

The Wolf Biermann Story

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1980 There is a life before death: The Wolf Biermann story John Shreve The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Shreve, John, "There is a life before death: The Wolf Biermann story" (1980). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5262. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5262 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 Th is is an unpublished m a n u s c r ip t in w h ic h c o p y r ig h t sub s i s t s . Any further r e p r in t in g of it s contents must be approved BY THE AUTHOR. Ma n s f ie l d L ib r a r y Un iv e r s it y o f-M ontana D ate: 198 0 THERE IS A LIFE BEFORE DEATH THE WOLF BIERMANN STORY by John Shreve B.A., University of Montana, 1976 Presented 1n p a rtial fu lfillm e n t of the requirements fo r the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1980 Approved by: & Chairman, Board of Examiners Deari% Graduate Scho6T S'-U- S'o Date UMI Number: EP40726 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Goethes Briefwechsel Mit Einem Kinde. Seinem Denkmal

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Prose Fiction Sophie 1959 Goethes Briefwechsel mit einem Kinde. Seinem Denkmal Bettina von Arnim Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sophiefiction Part of the German Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Arnim, Bettina von, "Goethes Briefwechsel mit einem Kinde. Seinem Denkmal" (1959). Prose Fiction. 6. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sophiefiction/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sophie at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Prose Fiction by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Bettina von Arnim Goethes Briefwechsel mit einem Kinde Seinem Denkmal Bettina von Arnim: Goethes Briefwechsel mit einem Kinde. Seinem Denkmal Erstdruck: Grünberg und Leipzig (Friedrich Wilhelm Levysohn) 1840. Textgrundlage ist die Ausgabe: Bettina von Arnim: Werke und Briefe. Herausgegeben von Gustav Konrad, Bde. 1–5, Frechen: Bartmann, 1959. Die Paginierung obiger Ausgabe wird hier als Marginalie zeilengenau mitgeführt. Erster Teil Dem Fürsten Pückler Haben sie von deinen Fehlen Immer viel erzählt, Und fürwahr, sie zu erzählen Vielfach sich gequält. Hätten sie von deinem Guten Freundlich dir erzählt, Mit verständig treuen Winken Wie man Bess’res wählt: O gewiß! Das Allerbeste Blieb uns nicht verhehlt, Das fürwahr nur wenig Gäste In der Klause zählt. – (Westöstlicher Divan Buch der Betrachtung) Es ist kein Geschenk des Zufalls oder der Laune, was Ihnen hier darge- bracht wird. Aus wohlüberlegten Gründen und mit freudigem Herzen biete ich Ihnen an, das Beste was ich zu geben vermag. Als Zeichen meines Dankes für das Vertrauen, was Sie mir schenken. -

Hermann Sudermann and the Liberal German Bourgeoisie

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses July 2016 Pessimism in Progress: Hermann Sudermann and the Liberal German Bourgeoisie Jason Doerre University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the European History Commons, German Literature Commons, and the Intellectual History Commons Recommended Citation Doerre, Jason, "Pessimism in Progress: Hermann Sudermann and the Liberal German Bourgeoisie" (2016). Doctoral Dissertations. 652. https://doi.org/10.7275/8322692.0 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/652 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PESSIMISM IN PROGRESS: HERMANN SUDERMANN AND THE LIBERAL GERMAN BOURGEOISIE A Dissertation Presented by JASON J. DOERRE Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2016 German and Scandinavian Studies © Copyright by Jason J. Doerre 2016 All Rights Reserved PESSIMISM IN PROGRESS: HERMANN SUDERMANN AND THE LIBERAL GERMAN BOURGEOISIE A Dissertation Presented by JASON J. DOERRE Approved as to style and content by: ____________________________________________________ -

Else Lasker-Schuler 3

Your Diamond Dreams Cut Open My Arteries COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES ImUNCI Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures From 1949 to 2004, UNC Press and the UNC Department of Germanic & Slavic Languages and Literatures published the UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures series. Monographs, anthologies, and critical editions in the series covered an array of topics including medieval and modern literature, theater, linguistics, philology, onomastics, and the history of ideas. Through the generous support of the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, books in the series have been reissued in new paperback and open access digital editions. For a complete list of books visit www.uncpress.org. Your Diamond Dreams Cut Open My Arteries Poems by Else Lasker-Schüler translated and with an introduction by robert p. newton UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures Number 100 Copyright © 1982 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons cc by-nc-nd license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons. org/licenses. Suggested citation: Lasker-Schüler, Else. Your Diamond Dreams Cut Open My Arteries: Poems by Else Lasker-Schüler. Translated by Robert P. Newton. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1982. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.5149/9781469656670_Lasker-Schuler Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Newton, Robert P. Title: Your diamond dreams cut open my arteries : Poems by Else Lasker-Schüler / by Robert P. Newton. Other titles: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures ; no. 100. Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [1982] Series: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures. -

Gedichte Von Johann Wolfgang Goethe

Gedichte von Johann Wolfgang Goethe Anklage Wißt ihr denn, auf wen die Teufel lauern, In der Wüste, zwischen Fels und Mauern? Und wie sie den Augenblick erpassen, Nach der Hölle sie entführend fassen? Lügner sind es und der Bösewicht. Der Poete, warum scheut er nicht, Sich mit solchen Leuten einzulassen! Weiß denn der, mit wem er geht und wandelt. Er, der immer nur im Wahnsinn handelt? Grenzenlos, von eigensinn'gem Lieben, Wird er in die Öde fortgetrieben, Seiner Klagen Reim', in Sand geschrieben, Sind vom Winde gleich verjagt; Er versteht nicht, was er sagt, Was er sagt, wird er nicht halten. Doch sein Lied, man läßt es immer walten, Da es doch dem Koran widerspricht. Lehret nun, ihr, des Gesetzes Kenner, Weisheit-fromme, hochgelahrte Männer, Treuer Mosleminen feste Pflicht. Hafis insbesondre schaffet Ärgernisse, Mirza sprengt den Geist ins Ungewisse, Saget, was man tun und lassen müsse? 1 Äolsharfen Gespräch Er Ich dacht, ich habe keinen Schmerz; Und doch war mir so bang ums Herz, Mir wars gebunden vor der Stirn Und hohl im innersten Gehirn – Bis endlich Trän auf Träne fließt, Verhaltnes Lebewohl ergießt. – Ihr Lebewohl war heitre Ruh, Sie weint wohl jetzund auch wie du. Sie Ja, er ist fort, das muß nun sein! Ihr Lieben, laßt mich nur allein; Sollt ich euch seltsam scheinen, Es wird nicht ewig währen! Jetzt kann ich ihn nicht entbehren, Und da muß ich weinen. Er Zur Trauer bin ich nicht gestimmt Und Freude kann ich auch nicht haben: Was sollen mir die reifen Gaben, Die man von jedem Baume nimmt! Der Tag ist mir zum Überdruß, Langweilig ists, wenn Nächte sich befeuern; Mir bleibt der einzige Genuß, Dein holdes Bild mir ewig zu erneuern.