The Press Behaving Badly: Unlawfully

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GEORGIA-FLORIDA 2018 FOOTBALL GAME Can’T Get to the Store? Saturday, Oct

THE FLORIDA STAR, NORTHEAST FLORIDA’S OLDEST, LARGEST, MOST READ AFRICAN AMERICAN OWNED NEWSPAPER The Florida Star Presorted Standard P. O. Box 40629 U.S. Postage Paid Jacksonville, FL 32203 Jacksonville, FL Permit No. 3617 GEORGIA-FLORIDA 2018 FOOTBALL GAME Can’t Get to the Store? Saturday, Oct. 27, 3:30 p.m. Have The Star Delivered! TIAA Bank Field, Jacksonville, FLA TV - CBS Read The Florida THE FLORIDA and Georgia Star STAR Newspapers. The only media thefl oridastar.com to receive the Listen to IMPACT Jacksonville Sheriff’s Radio Talk Show. Offi ce Eagle The people’s choice Award for being “The Most Factual.” OCTOBER 27 - NOVEMBER 2, 2018 VOLUME 68, NUMBER 29 $1.00 CAMPAIGNING IN JACKSONVILLE A Blue Wave lorida Senator Bill Nelson, for- mer Vice Presi- Fdent Joe Biden, Tal- Is Needed for lahassee Mayor and Democratic nominee for Florida Governor Guys Like John Andrew Gillum, and Chris King of Orlando, Florida is in desperate need of Fla. Gillum running mate for Lieutenant criminal justice system reform. Governor on the Dem- ocratic ticket, visited By Opio Sokoni, MSCJ, JD UNF on Monday, Oc- tober 22, 2018. See in- ohn A. Bogins, a nonviolent, low level drug offender, is side for story and pic- sentenced to thirty years in prison in the state of Florida tures. Photo by Frank even though he has never raped, killed or beaten anyone. M. Powell, III When the Federal government began ACT OF TERROR EWC HOMECOMING tryingJ to make sense out of the harsh reality that the drug Explosive Devices war has placed us in as a country, states like Florida Sent to Obama, remained stuck. -

Jacksonville Civil Rights History Timelinetimeline 1St Revision 050118

Jacksonville Civil Rights History TimelineTimeline 1st Revision 050118 Formatted: No underline REVISION CODES Formatted: Underline Formatted: Centered Strike through – delete information Yellow highlight - paragraph needs to be modified Formatted: Highlight Formatted: Centered Green highlight - additional research needed Formatted: Highlight Formatted: Highlight Grey highlight - combine paragraphs Formatted: Highlight Light blue highlight – add reference/footnote Formatted: Highlight Formatted: Highlight Grey highlight/Green underline - additional research and combine Formatted: Highlight Formatted: Highlight Red – keep as a reference or footnote only Formatted: Highlight Formatted: Thick underline, Underline color: Green, Highlight Formatted: Thick underline, Underline color: Green, Highlight Formatted: Highlight Formatted: No underline, Underline color: Auto Page 1 of 54 Jacksonville Civil Rights History TimelineTimeline 1st Revision 050118 Formatted: Font: Not Bold 1564 Fort Caroline was built by French Huguenots along St. Johns Bluff under the Formatted: Font: Not Bold, Strikethrough command of Rene Goulaine de Laudonniere. The greater majority of the settlers Formatted: Strikethrough were also Huguenots, but were accompanied by a small number of Catholics, Formatted: Font: Not Bold, Strikethrough agnostic and “infidels”. One historian identified the “infidels” as freemen from Formatted: Strikethrough Africa. Formatted: Font: Not Bold, Strikethrough Formatted: Strikethrough 1813 A naturalized American citizen of British ancestry, Zephaniah Kingsley moved to Formatted: Font: Not Bold, Strikethrough Fort George Island at the mouth of the St. Johns River. Pledging allegiance to Formatted: Strikethrough Spanish authority, Kingsley became wealthy as an importer of merchant goods, Formatted: Font: Not Bold, Strikethrough seafarer, and slave trader. He first acquired lands at what is now the City of Orange Formatted: Strikethrough Park. There he established a plantation called Laurel Grove. -

PHILANTHROPIST, ENTREPRENEUR and RECORDING ARTIST

THE FLORIDA STAR, NORTHEAST FLORIDA’S OLDEST, LARGEST, MOST READ AFRICAN AMERICAN OWNED NEWSPAPER The Florida Star Presorted Standard P. O. Box 40629 U.S. Postage Paid Jacksonville, FL 32203 Jacksonville, FL Philanthropic Families Donate More Permit No. 3617 Than Half A Million Dollars to Can’t Get to the Store? Bethune-Cookman University Have The Star Delivered! Story on page 6 Read The Florida and Georgia Star THE FLORIDA Newspapers. STAR thefl oridastar.com The only media Listen to IMPACT to receive the Radio Talk Show. Jacksonville Sheriff’s The people’s choice Offi ce Eagle Award for being “The Most Factual.” APRIL 11 - APRIL 17, 2020 VOLUME 69, NUMBER 52 $1.00 Daughter of MLK Named PHILANTHROPIST, to Georgia ENTREPRENEUR and Coronavirus RECORDING ARTIST Outreach Group Keeve Murdered eeve Hikes, Philanthropist, entre- preneur and rapper from Jack- sonville, Florida was fatally shot Tuesday evening. Keeve was pro- nounced dead on the scene, ac- cordingK to offi cials. News of his death, prompted an out- pouring of support from the Jacksonville Florida community. Dr. Bernice King, daughter of civil rights “May His peace comfort you all leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. will help lead a new outreach committee in Georgia during this diffi cult time. His life was a as the state copes with the coronavirus, Gov. Testament of time well spent.” Brian Kemp announced Sunday. Keeve drew attention for industry King, chief executive offi cer of the Martin leaders from his hit single “ Bag” Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social feat. YFN Lucci, from his album en- Change in Atlanta, will co-chair the commit- titled “ No Major Deal But I’m Still tee of more than a dozen business and com- Major”. -

The Remains of Privacy's Disclosure Tort: an Exploration of the Private Domain Jonathan B

Maryland Law Review Volume 55 | Issue 2 Article 7 The Remains of Privacy's Disclosure Tort: an Exploration of the Private Domain Jonathan B. Mintz Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr Part of the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Jonathan B. Mintz, The Remains of Privacy's Disclosure Tort: an Exploration of the Private Domain, 55 Md. L. Rev. 425 (1996) Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/mlr/vol55/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Academic Journals at DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maryland Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UM Carey Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE REMAINS OF PRIVACY'S DISCLOSURE TORT: AN EXPLORATION OF THE PRIVATE DOMAIN JONATHAN B. MINTZ* TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................. 426 I. COMMON-LAW AND STATUTORY DIMENSIONS OF THE TO RT ................................................... 427 A. The Concept of Privacy................................ 427 B. Legal Categorizationsof Privacy ....................... 429 C. The Contours of the Tort of Public Disclosure of Private Facts ................................................ 436 1. Publicity ......................................... 437 2. Highly Offensive Matter Concerning Another's Private Life ............................................. 43 8 3. Not of Legitimate Concern to the Public ............. 441 II. THE VIABILIT' OF THE TORT ............................. 448 A. The Supreme Court's Disclosure Tort Jurisprudence....... 448 1. Cox Broadcasting Corp. v. Cohn ................ 449 2. Smith v. Daily Mail Publishing Co ............... 450 3. Florida Star v. B.J.F ............................. 451 B. The Searchfor Remains ............................... 454 III. DEFINING THE REMAINS: WHAT AND WHERE Is THE PRIVATE DOMAIN? ....................................... 457 A. -

Constitutional Protection of a Rape Victim's Privacy

St. John's Law Review Volume 66 Number 1 Volume 66, Winter 1992, Number 1 Article 5 Raped Once, But Violated Twice: Constitutional Protection of a Rape Victim's Privacy Gary F. Giampetruzzi Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/lawreview This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in St. John's Law Review by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTES RAPED ONCE, BUT VIOLATED TWICE: CONSTITUTIONAL PROTECTION OF A RAPE VICTIM'S PRIVACY INTRODUCTION During the early morning hours of March 30, 1991, a twenty- nine-year-old woman was allegedly raped by William Kennedy Smith, the thirty-year-old nephew of Massachusetts Senator Ed- ward Kennedy.' On April 7, 1991, her identity was disclosed in The Sunday Mirror, a British tabloid.2 On April 15, 1991, her identity was further publicized in the Globe, a supermarket tabloid based in Boca Raton, Florida.3 On April 16, 1991, NBC's "Nightly News" became the largest mainstream news organization to identify the alleged rape victim.4 Finally, on April 17, 1991, one of the nation's most circumspect newspapers, The New York Times, published a I Kennedy Nephew Arrested, Facts on File, May 16, 1991, at 358E3, available in DIA- LOG. On May 9, 1991, William Kennedy Smith was formally charged in connection with the alleged rape. Id. On May 11, 1991, he surrendered to police. -

Canaveral National Seashore Historic Resource Study

Canaveral National Seashore Historic Resource Study September 2008 written by Susan Parker edited by Robert W. Blythe This historic resource study exists in two formats. A printed version is available for study at the Southeast Regional Office of the National Park Service and at a variety of other repositories around the United States. For more widespread access, this administrative history also exists as a PDF through the web site of the National Park Service. Please visit www.nps.gov for more information. Cultural Resources Division Southeast Regional Office National Park Service 100 Alabama Street, SW Atlanta, Georgia 30303 404.562.3117 Canaveral National Seashore 212 S. Washington Street Titusville, FL 32796 http://www.nps.gov/cana Canaveral National Seashore Historic Resource Study Contents Acknowledgements - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - vii Chapter 1: Introduction - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 1 Establishment of Canaveral National Seashore - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 1 Physical Environment of the Seashore - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 2 Background History of the Area - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 2 Scope and Purpose of the Historic Resource Study - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 3 Historical Contexts and Themes - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 4 Chapter Two: Climatic Change: Rising Water Levels and Prehistoric Human Occupation, ca. 12,000 BCE - ca. 1500 CE - - - - -

Retroactively Classified Documents, the First Amendment, and the Power to Make Secrets out of the Public Record

ARTICLE DO YOU HAVE TO KEEP THE GOVERNMENT’S SECRETS? RETROACTIVELY CLASSIFIED DOCUMENTS, THE FIRST AMENDMENT, AND THE POWER TO MAKE SECRETS OUT OF THE PUBLIC RECORD JONATHAN ABEL† INTRODUCTION ............................................................................ 1038 I. RETROACTIVE CLASSIFICATION IN PRACTICE AND THEORY ... 1042 A. Examples of Retroactive Classification .......................................... 1043 B. The History of Retroactive Classification ....................................... 1048 C. The Rules Governing Retroactive Classification ............................. 1052 1. Retroactive Reclassification ............................................... 1053 2. Retroactive “Original” Classification ................................. 1056 3. Retroactive Classification of Inadvertently Declassified Documents .................................................... 1058 II. CAN I BE PROSECUTED FOR DISOBEYING RETROACTIVE CLASSIFICATION? ............................................ 1059 A. Classified Documents ................................................................. 1059 1. Why an Espionage Act Prosecution Would Fail ................. 1061 2. Why an Espionage Act Prosecution Would Succeed ........... 1063 3. What to Make of the Debate ............................................. 1066 B. Retroactively Classified Documents ...............................................1067 1. Are the Threats of Prosecution Real? ................................. 1067 2. Source/Distributor Divide ............................................... -

Interpreting Racial Politics

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Interpreting Racial Politics: Black and Mainstream Press Web Site Tea Party Coverage Benjamin Rex LaPoe II Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation LaPoe II, Benjamin Rex, "Interpreting Racial Politics: Black and Mainstream Press Web Site Tea Party Coverage" (2013). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 45. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/45 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. INTERPRETING RACIAL POLITICS: BLACK AND MAINSTREAM PRESS WEB SITE TEA PARTY COVERAGE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Manship School of Mass Communication by Benjamin Rex LaPoe II B.A. West Virginia University, 2003 M.S. West Virginia University, 2008 August 2013 Table of Contents Abstract .......................................................................................................................................... iii Introduction -

The Power 100

SPECIAL FEATURE | the PoweR 100 THE POWER 100 The brains behind the poltical players that shape our nation, the media minds that shape our opinions, the developers who revitalize our region, and the business leaders and philanthropists that are always pushing the envelope ... power, above all, is influence he Washington socialite-hostess gathers the ripe fruit of These things by their very nature cannot remain static – political, economic, and cultural orchards and serves it and therefore our list changes with the times. Tup as one fabulous cherry bombe at a charity fundraiser Power in Washington is different than in other big cities. or a private soirée with Cabinet secretaries and other major Unlike New York, where wealth-centric power glitters with political players. Two men shake hands in the U.S. Senate and the subtlety of old gold, wealth doesn’t automatically confer a bill passes – or doesn’t. The influence to effect change, be it power; in Washington, rather, it depends on how one uses it. in the minds or actions of one’s fellow man, is simultaneously Washington’s power is fundamentally colored by its the most ephemeral quantity (how does one qualify or rate proximity to politics, and in this presidential season, even it?) and the biggest driving force on our planet. more so. This year, reading the tea leaves, we gave a larger nod In Washington, the most obvious source of power is to the power behind the candidates: foreign policy advisors, S È political. However, we’ve omitted the names of those who fundraisers, lobbyists, think tanks that house cabinets-in- draw government paychecks here, figuring that it would waiting, and influential party leaders. -

Florida Newspaper History Chronology, 1783-2001

University of South Florida Digital Commons @ University of South Florida USF St. Petersburg campus Faculty Publications USF Faculty Publications 2019 Florida Newspaper History Chronology, 1783-2001 David Shedden [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/fac_publications Part of the Journalism Studies Commons, Mass Communication Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Shedden, D. (2019). Florida Newspaper History Chronology, 1783-2001. Digital Commons @ University of South Florida. This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the USF Faculty Publications at Digital Commons @ University of South Florida. It has been accepted for inclusion in USF St. Petersburg campus Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ University of South Florida. For more information, please contact [email protected]. __________________________________________ Florida Newspaper History Chronology 1783-2001 The East-Florida Gazette, Courtesy Florida Memory Program By David Shedden Updated September 17, 2019 __________________________________________ CONTENTS • INTRODUCTION • CHRONOLOGY (1783-2001) • APPENDIXES Daily Newspapers -- General Distribution Weekly Newspapers and other Non-Dailies -- General Distribution African-American Newspapers College Newspapers Pulitzer Prize Winners -- Florida Newspapers Related Resources • BIBLIOGRAPHY 2 INTRODUCTION Our chronology looks at the history of Florida newspapers. It begins in 1783 during the last days of British rule and ends with the first generation of news websites. Old yellowed newspapers, rolls of microfilm, and archived web pages not only preserve stories about the history of Florida and the world, but they also give us insight into the people who have worked for the state’s newspapers. This chronology only scratches the surface of a very long and complex story, but hopefully it will serve as a useful reference tool for researchers and journalism historians. -

12-10-2011.Pdf

PQTVJGCUV"HNQTKFC‚U"QNFGUV."NCTIGUV."OQUV"TGCF"CHTKECP"COGTKECP"QYPGF"PGYURCRGT URQTVU"/"D/6 Vjg"Hnqtkfc"Uvct Rtguqtvgf"Uvcpfctf Vjg"Hnqtkfc"Uvct. R0"Q0"Dqz"6284; W0U0"Rquvcig"Rckf Lcemuqpxknng."HN Vjg"Igqtikc"Uvct# Lcemuqpxknng."HN"54425 Rgtokv""Pq0"5839 Vcnm"qh"vjg"Vqyp Korcev"Tcfkq Can’t Get to the Store C/6 CO3582 Cpvjqp{"Jcoknvqp."Tkemg{"Uokng{ *;26+"988/::56 Have The Star Delivered Ugg"Etkog"("Lwuvkeg RtgrTcr"/"Qwt"[qwvj Ugg""D/3 UKPEG"3;73 Cp"Cyctf Tgcf"Vjg"Hnqtkfc cpf"Igqtikc"Uvct Ykppkpi Pgyurcrgtu0 Rwdnkecvkqp. Nkuvgp vq"KORCEV ugtxkpi"{qw Tcfkq"Vcnm"Ujqy0 ukpeg"3;730" YYY0vjghnqtkfcuvct0eqo Tcvgf"›Cfi"d{ Still the people’s vjg"Dgvvgt choice, striving to Dwukpguu"Dwtgcw yyy0vjghnqtkfcuvct0eqo make a difference. FGEGODGT"32."4233"/"FGEGODGT"38."4233""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""XQN0"83"PQ0"56"""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""72"EGPVU Ycpvgf Okuukpi Lcemuqpxknng"Ngcf"Uvcvg"cpf"Pcvkqp Vkigt"Ykpu Hgocng kp"Vggp"Rtgipcpe{"Tcvgu Cickp Since the last teen pregnancy study was conducted nearly 30 years ago by JCCI that resulted in the estab- lishment of The Bridge of Northeast Florida (recom- mendation of a model multi-service teen center), teen birth rates have declined. Yet, area teens continue to give birth at a higher rate than teens throughout the state and nation, according to the new Task Force report – Preventing Teen Pregnancy in Northeast Name: Natasha Dovie Florida. Robert Fleming Bradwell Wilson, Age: 16 Several organizations are coming together to form a III, 08/08/1982. Last See Crime & Justice task force to educate teens regarding pregnancy and known address was on Section each week for STDs. Presently 78% of Baker County teens had Mount Herman St., missing children of babies and 36.5% of Jacksonville teens had babies. -

2005 Annual Report

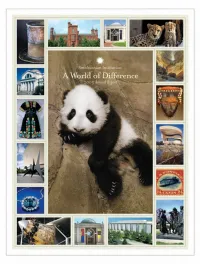

from the secretary E very day, Smithsonian scientists, researchers, and curators make a difference in the world around us. Achievement is our hallmark, but even by our standards, 2005 has been a remarkable year. We welcomed our first giant panda cub, Tai Shan, on July 9, born after National Zoo scientists artificially inseminated mother Mei Xiang, successfully culminating nearly a decade of work with giant pandas that will help to save the species in nature. We were the grateful recipients of the magnificent Walt Disney-Tishman Collection of African art, which, when combined with our own holdings, gives us a collection unparalleled in the United States. And we celebrated two major openings: The National Museum of American History, Behring Center’s sweeping The Price of Freedom: Americans at War, examining the impact of military involvements throughout American history, and the National Air and at the smithsonian, Space Museum’s James S. McDonnell Space we share what we Hangar at the Udvar-Hazy Center, home of have and use what the space shuttle Enterprise. Generous donors we know to connect — whose passion for discovery and preserva- people and ideas. tion matches our own — made these stellar accomplishments possible. This year, we received a breathtaking $45 million donation from the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation to help restore the landmark Patent Office Building. This extraordinary gift caps a banner fund-raising year in which the Smithsonian raised $168.8 million, including $11 million in endowed directorship gifts that build the stability and financial strength of the Institution, making us better stewards of the future.