Survivor Testimony Booklet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Record—Senate S5702

S5702 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE September 25, 2019 TRANSMITTAL NO. 19–47 to pursuing an education at the U.S. serving as a visionary guardian of the Notice of Proposed Issuance of Letter of Military Academy, to earning the rank country’s well-being. Hailing from Offer Pursuant to Section 36(b)(1) of the of Supreme Commander of Allied America’s heartland and devoting his Arms Export Control Act Forces in Europe during World War II, life to the pursuit of liberty, Ike left Annex Item No. vii to becoming the leader of our Nation behind an extraordinary legacy that (vii) Sensitivity of Technology: and the free world, Ike continually created a better, more peaceful world. 1. The AN/AAQ–24(V)N LAIRCM is a self- strived for the best. Like so many of f contained, directed energy countermeasures his generation, he achieved a great deal system designed to protect aircraft from in- for himself and our country, but didn’t ADDITIONAL STATEMENTS frared-guided surface-to-air missiles. The seek personal credit for his accom- system features digital technology and plishments. Eisenhower’s determina- micro-miniature solid-state electronics. The REMEMBERING MARCA BRISTO tion, leadership, and honorable char- system operates in all conditions, detecting ∑ Ms. DUCKWORTH. Mr. President, I incoming missiles and jamming infrared- acter are the reasons that he remains seeker equipped missiles with aimed bursts respected around the world to this day. come before the Senate today to honor of laser energy. The LAIRCM system con- In fact, just 2 years ago in 2017, histo- the life of Marca Bristo: a trailblazer, sists of multiple Missile Warning Sensors, rians with expertise on Presidential an activist, a mother and—to me and Guardian Laser Turret Assembly (GLTA), rankings revised previous figures to so many others—a hero. -

A Plan for Allocating Successor Organization Resources

A Plan for Allocating Successor Organization Resources Report of the Planning Committee, Conference On Jewish Material Claims Against Germany June 28, 2000 25 Sivan 5760 1 Rabbi Israel Miller, President, Conference On Jewish Material Claims Against Germany 15 East 26 Street New York, New York Dear Israel, I am pleased to enclose A Plan for Allocating Successor Organization Resources, the report of the distinguished Planning Committee which I have had the honor of chairing. The Committee has completed a thoughtful ten-month process, carefully reviewing the issues and exploring a variety of options before coming to the conclusions contained in this document. We trust that you will bring these recommendations to the Board of Directors of the Claims Conference for review and action. Through this experience, I have become convinced that the work of the Claims Conference is not adequately understood or appreciated. I hope that this report and the results of this planning process will help dispel the confusion about the past and future achievements of the Claims Conference. No amount of money can compensate for the destruction of innocent human beings and thriving communities or the decimation of the Jewish people as a whole by the Nazis. We can try to use available resources - specifically the proceeds of the sale of communal and unclaimed property in the former East Germany - to respond to the most critical needs related to the consequences of the Shoah. This is what the enclosed Plan tries to accomplish. I want to thank the members of the Committee who came from near and far for their attendance and commitment, and for the high quality of their participation. -

December 2019 Kislev-Tevet 5780

In This Issue: New Website, page3 Welcome New Members, page 4 Membership Directory 2020, page 5 VOLUME 16 NUMBER 4 DECEMBER 2019 KISLEV-TEVET 5780 WOK N’ ROLL HANUKKAH DINNER & MOVIE What do most Jews do on December 24? Order Chinese food and go to a movie, of course! This year it falls on the third night of Hanukkah, so why not join your friends and celebrate at Beth Abraham. Bring your Hanukkah menorahs and candles to light together, enjoy a delicious vegetarian Chinese dinner and latkes prepared by our in-house clergy catering service and then prepare to laugh at a movie classic fit for the season, “Monty Python’s Life of Brian.” There will also be a movie just for the kids, along with games and other Hanukkah activities. The fun begins at 5:30PM. $10 adults, $6 kids 12 and under. Please RSVP to the office by Wednesday, December 18. New Art Panels to be Installed Outside the Sanctuary During this anniversary year, we have learned many lessons. In particular, we are once again reminded that our successes during our first 125 years are largely based on our constantly working in partnership to provide a spiritual home that meets so many of our individual needs; we are again reminded that, indeed, it takes a village! This life lesson is symbolized by an anniversary project undertaken by the Kaleidoscope of Us subcommittee. At and after its hugely successful August 25th “From Babies to Bubbies” event, over 50 of us, from the very young to those not so young, participated in the creation of an art piece designed by Lois Gross, our own “artist-in-residence.” Lois designed four abstract panels that depict aspects of Jewish life. -

Index of Subjects

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-83875-7 - Jewish Forced Labor Under the Nazis: Economic Needs and Racial Aims, 1938-1944 Wolf Gruner Index More information Index of Subjects Aktion Erntefest, 271 Autobahn camps, 286 Aktion Hase, 96 acceptance/rejection of Jews for, 197, Aktion Mitte B, 97 198 Aktion Reinhard, 258 administration of by private companies, Aktion T4, 226 203 Allgemeine Ortskrankenkasse (AOK). See closing of, 208, 209, 211 General Local Health Insurance control of by Autobahn authorities, 199, Provider. 203, 213, 219 Annexation of Austria. See Anschluss. control of by SS (Schmelt), 214, 223 Anschluss (annexation of Austria), xvi, xxii, employing Polish Jews, 183, 198, 203, 3, 105, 107, 136, 278 217, 286 Anti-Jewish policy locations of, 203, 212, 219, 220 before 1938, xx, xxii, xxiv redesignation of as “Zwangsarbeitslager,” central measures in, xxi, xxii, xxiii 223 consequences of for Jews, xvi, 107, 109, regulations for, 199, 200, 203, 212 131, 274 See also Fuhrer’s¨ road and Schmelt forced contradiction in, 109 labor camps. diminished SS role in, 240, 276 Autobahn construction management division of labor principle in, xvii, xviii, headquarters (Oberste Bauleitung der xxiv, 30, 112, 132, 244, 281, 294 Reichsautobahnen) effect of war on, 8, 9, 126, 141, 142 in Austria, 127 forced labor as element of, x, xii, xiii, 3, 4, in Berlin, 199, 200, 202, 203, 204, 205, 177, 276 206 in Austria, 136 in Breslau, 204, 205, 211, 212, 220, local-central interaction in, xx, xxi, xxii 222 local measures in, xxi, xxii, xxiii, 150, in Cologne, 205 151 in Danzig, 203, 204, 205 measures implementing, 151, 172, 173, See also Reich Autobahn Directorates. -

Additional Research Notes

Additional Research Notes Below is more information related to Joe’s story, including concen tration camps, ship transporting dislocated persons, camp for dislocated persons, camp commandants/other Nazi officials and their fate, and famous shoe companies. 1. Concentration Camps A. Auschwitz/Birkenau, Poland (Concentration Camp) Author’s Note : Joe arrived at Auschwitz on April 30, 1942 and was housed at its sister camp, Birkenau, or “Auschwitz II,” where two days a week he was forced to move the bodies of the dead from the gas chamber to open pits. He was also required to do daily calisthenics and work in many other areas around the camp, including snow removal on the massive grounds. Joe was eventually assigned to a slave labor crew working in a nearby coal mine. For a short while, the inmate miners were forced to walk several miles each day to the coal mine and back. When Joe was finally moved from Birkenau to a camp near the coal mine, he le Auschwitz for the last time, but the mining camp remained under the authority of Auschwitz. Joe permanently lost the hearing in one ear from the repeated explosions of dynamite. Documents provided by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., show that in June 1944, Joe (Juzek Rubinsztein) was sent from the Auschwitz complex (we believe from the Jawischowitz Sub-camp/Brzeszcze Coal Mine) to Buchenwald, Germany. His official number while at Auschwitz was 34207. At Buchenwald, his number was 117.666. 1, 2 e Auschwitz Concentration Camp, located thirty-seven miles west of Krakow, near the Polish city of Oswiecim, was in an area annexed by Nazi Germany in 1939 aer its invasion of Poland. -

Maharam of Padua V. Giustiniani; the Sixteenth-Century Origins of the Jewish Law of Copyright

Draft: July 2007 44 Houston Law Review (forthcoming 2007) Maharam of Padua v. Giustiniani; the Sixteenth-Century Origins of the Jewish Law of Copyright Neil Weinstock Netanel* Copyright scholars are almost universally unaware of Jewish copyright law, a rich body of copyright doctrine and jurisprudence that developed in parallel with Anglo- American and Continental European copyright laws and the printers’ privileges that preceded them. Jewish copyright law traces its origins to a dispute adjudicated some 150 years before modern copyright law is typically said to have emerged with the Statute of Anne of 1709. This essay, the beginning of a book project about Jewish copyright law, examines that dispute, the case of the Maharam of Padua v. Giustiniani. In 1550, Rabbi Meir ben Isaac Katzenellenbogen of Padua (known by the Hebrew acronym, the “Maharam” of Padua) published a new edition of Moses Maimonides’ seminal code of Jewish law, the Mishneh Torah. Katzenellenbogen invested significant time, effort, and money in producing the edition. He and his son also added their own commentary on Maimonides’ text. Since Jews were forbidden to print books in sixteenth- century Italy, Katzenellenbogen arranged to have his edition printed by a Christian printer, Alvise Bragadini. Bragadini’s chief rival, Marc Antonio Giustiniani, responded by issuing a cheaper edition that both copied the Maharam’s annotations and included an introduction criticizing them. Katzenellenbogen then asked Rabbi Moses Isserles, European Jewry’s leading juridical authority of the day, to forbid distribution of the Giustiniani edition. Isserles had to grapple with first principles. At this early stage of print, an author- editor’s claim to have an exclusive right to publish a given book was a case of first impression. -

The Memoirs of an Unwanted Witness--A Soviet Spymaster Ebook

SPECIAL TASKS: THE MEMOIRS OF AN UNWANTED WITNESS--A SOVIET SPYMASTER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Anatoli Sudoplatov, Pavel Sudoplatov, Leona P Schecter, Jerrold L Schecter | 576 pages | 01 Jun 1995 | Little, Brown & Company | 9780316821155 | English | Boston, MA, United States Lord of the spies: The 4 most impressive operations by Stalin’s chief spymaster - Russia Beyond Robert Oppenheimer and Leo Szilard, all of whom are dead and were eminent scientists. Both Dr. Bohr and Dr. Fermi won the Nobel Prize for basic discoveries in physics, the former in and the latter in Szilard, a Hungarian, was the chief physicist for the Manhattan Project, the nation's atom bomb project. Oppenheimer was the scientific director of the Los Alamos laboratory in the mountains of New Mexico during the war. The scientists there built the nuclear bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The book, which offered little evidence other than Mr. Sudoplatov's recollections to back up its accusations, was excerpted in Time on April 25, , and ignited a global controversy as outraged scientists and historians rushed to defend the dead luminaries. Aspin had asked for the review on March Director, Louis J. Given Moscow's remarkable successes in placing Fuchs and Donald Maclean as atom spies, it would be brave to declare categorically that none of these four - Oppenheimer, Fermi, Szilard or Bohr - could possibly have been agents, or at least helpful sympathisers. But to assert, without supporting evidence, that they all were, is to smear them. These are four of the inspirational figures of modern physics: they deserve better. Independent Premium Comments can be posted by members of our membership scheme, Independent Premium. -

Smith's Report, No

SMITH’S REPORT On the Holocaust Controversy No. 146 www.Codoh.com January 2008 Challenging the Holocaust Taboo Since 1990 THE MAN WHO SAW HIS OWN LIVER Introduction: Death and Taxes Richard “Chip” Smith Nine Banded Books is a new publishing house that has chosen to make my manu- script, The Man Who Saw His Own Liver, its first publication, which is an honor I very much appreciate. Chip Smith is the head honcho there and has done everything right, be- ginning with the imaginative idea of transposing the format of my one-character play, The Man Who Stopped Paying, into that of a short novel, The Man Who Saw His Own Liver. Not one word has been changed. It has been formatted in a simple, unique, and imaginative way, and is followed by a coda that, again, is an imaginative choice that never would have occurred to me. The Man Who Saw His Own Liver is at the printer now and we expect to have it to hand the first week in February. Following is the elegant and rather brilliant introduction written by the publisher. radley Smith is one of those writers. Like Hunter Thompson or Hubert Selby; like B Brautigan, Bukowski, or the Beats. You read him when you’re young. You read him with a rush of discovery never to be forgotten. The prose is clean and relaxed and punctuated with a distinct, tumbling, rhythmic flair. It goes down easy. It makes you want to write. The world Smith made is suffused with a restless vitality that feels personal and true. -

Study Guide REFUGE

A Guide for Educators to the Film REFUGE: Stories of the Selfhelp Home Prepared by Dr. Elliot Lefkovitz This publication was generously funded by the Selfhelp Foundation. © 2013 Bensinger Global Media. All rights reserved. 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgements p. i Introduction to the study guide pp. ii-v Horst Abraham’s story Introduction-Kristallnacht pp. 1-8 Sought Learning Objectives and Key Questions pp. 8-9 Learning Activities pp. 9-10 Enrichment Activities Focusing on Kristallnacht pp. 11-18 Enrichment Activities Focusing on the Response of the Outside World pp. 18-24 and the Shanghai Ghetto Horst Abraham’s Timeline pp. 24-32 Maps-German and Austrian Refugees in Shanghai p. 32 Marietta Ryba’s Story Introduction-The Kindertransport pp. 33-39 Sought Learning Objectives and Key Questions p. 39 Learning Activities pp. 39-40 Enrichment Activities Focusing on Sir Nicholas Winton, Other Holocaust pp. 41-46 Rescuers and Rescue Efforts During the Holocaust Marietta Ryba’s Timeline pp. 46-49 Maps-Kindertransport travel routes p. 49 2 Hannah Messinger’s Story Introduction-Theresienstadt pp. 50-58 Sought Learning Objectives and Key Questions pp. 58-59 Learning Activities pp. 59-62 Enrichment Activities Focusing on The Holocaust in Czechoslovakia pp. 62-64 Hannah Messinger’s Timeline pp. 65-68 Maps-The Holocaust in Bohemia and Moravia p. 68 Edith Stern’s Story Introduction-Auschwitz pp. 69-77 Sought Learning Objectives and Key Questions p. 77 Learning Activities pp. 78-80 Enrichment Activities Focusing on Theresienstadt pp. 80-83 Enrichment Activities Focusing on Auschwitz pp. 83-86 Edith Stern’s Timeline pp. -

Feeding France's Outcasts: Rationing in Vichy's Internment Camps, 1940

Feeding France’s Outcasts: Rationing and Hunger in Vichy’s Internment Camps, 1940-1944 by Laurie Drake A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto © Copyright by Laurie Drake November 2020 Feeding France’s Outcasts: Rationing in Vichy’s Internment Camps, 1940-1944 Laurie Drake Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto November 2020 Abstract During the Second World War, Vichy interned thousands of individuals in internment camps. Although mortality remained relatively low, morbidity rates soared, and hunger raged throughout. How should we assess Vichy’s role and complicity in the hunger crisis that occurred? Were caloric deficiencies the outcome of a calculated strategy, willful neglect, or an unexpected consequence of administrative detention and wartime penury? In this dissertation, I argue that the hunger endured by the thousands of internees inside Vichy’s camps was not the result of an intentional policy, but rather a reflection of Vichy’s fragility as a newly formed state and government. Unlike the Nazis, French policy-makers never created separate ration categories for their inmates. Ultimately, food shortage resulted from the general paucity of goods arising from wartime occupation, dislocation, and the disruption of traditional food routes. Although these problems affected all of France, the situation was magnified in the camps for two primary reasons. First, the camps were located in small, isolated towns typically ii not associated with large-scale agricultural production. Second, although policy-makers attempted to implement solutions, the government proved unwilling to grapple with the magnitude of the problem it faced and challenge the logic of confinement, which deprived people of their autonomy, including the right to procure their own food. -

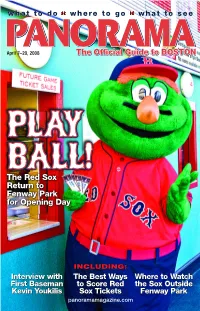

The Red Sox Return to Fenway Park for Opening Day

what to do • where to go • what to see April 7–20, 2008 Th eeOfOfficiaficialficial Guid eetoto BOSTON The Red Sox Return to Fenway Park for Opening Day INCLUDING:INCLUDING: Interview with The Best Ways Where to Watch First Baseman to Score Red the Sox Outside Kevin YoukilisYoukilis Sox TicketsTickets Fenway Park panoramamagazine.com BACK BY POPULAR DEMAND! OPENS JANUARY 31 ST FOR A LIMITED RUN! contents COVER STORY THE SPLENDID SPLINTER: A statue honoring Red Sox slugger Ted Williams stands outside Gate B at Fenway Park. 14 He’s On First Refer to story, page 14. PHOTO BY E THAN A conversation with Red Sox B. BACKER first baseman and fan favorite Kevin Youkilis PLUS: How to score Red Sox tickets, pre- and post-game hangouts and fun Sox quotes and trivia DEPARTMENTS "...take her to see 6 around the hub Menopause 6 NEWS & NOTES The Musical whe 10 DINING re hot flashes 11 NIGHTLIFE Men get s Love It tanding 12 ON STAGE !! Too! ovations!" 13 ON EXHIBIT - CBS Mornin g Show 19 the hub directory 20 CURRENT EVENTS 26 CLUBS & BARS 28 MUSEUMS & GALLERIES 32 SIGHTSEEING Discover what nearly 9 million fans in 35 EXCURSIONS 12 countries are laughing about! 37 MAPS 43 FREEDOM TRAIL on the cover: 45 SHOPPING Team mascot Wally the STUART STREET PLAYHOUSE • Boston 51 RESTAURANTS 200 Stuart Street at the Radisson Hotel Green Monster scores his opening day Red Sox 67 NEIGHBORHOODS tickets at the ticket ofofficefice FOR TICKETS CALL 800-447-7400 on Yawkey Way. 78 5 questions with… GREAT DISCOUNTS FOR GROUPS 15+ CALL 1-888-440-6662 ext. -

1000 Ans De Vie Juive En Pologne Une Chronologie. Traduit Par Natalia Krasicka

de vie juiveans en Pologne 1000 ans de vie juive en Pologne une chronologie. Traduit par Natalia Krasicka Version française réalisé par le en coopération avec la Taube Foundation for Jewish Life & Culture et le Consul honoraire de la République de Pologne, région de la Baie de San Francisco Le projet est cofi nancé par le Ministère des Affaires Étrangères de la République de Pologne. Les opinions exprimées dans la présente publication n’engagent que leur auteur et ne refl ètent pas le point de vue offi ciel du Ministère des Affaires Étrangères de la République de Pologne. La présente version linguistique est réalisée dans le cadre du projet « Histoire commune, nouveaux chapitres ». En hébreu, Pologne se dit Polin (ce qui signifi e « repose-toi ici » ou « habite ici »). En effet, au cours de l’histoire, les Juifs ont la plupart du temps trouvé en Pologne un lieu où se reposer, habiter et se sentir chez eux. L’histoire des Juifs polonais est certes lourde de traumatismes mais elle est aussi porteuse de créativité et de réalisations cultu- relles extraordinaires. C’est une histoire faite de récits interdépendants. Cette chronologie en fournit les dates clés, elle présente les personnalités et les tendances qui illustrent la richesse et la complexité de ces mille ans de vie des Juifs de Pologne. I. POLIN: ÉTABLISSEMENT DES JUIFS EN POLOGNE, 965-1569 965-966 Un commerçant juif d’Espagne, Ibrahim ibn Yaqub, voyage en Pologne et rédige les premières descriptions du pays. Aux Xe et XIe siècles, des marchands et des artisans juifs s’éta- blissent en Pologne.