'Undercliff' of the Isle of Wight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historic Environment Action Plan the Undercliff

Directorate of Community Services Director Sarah Mitchell Historic Environment Action Plan The Undercliff Isle of Wight County Archaeology and Historic Environment Service October 2008 01983 823810 archaeology @iow.gov.uk Iwight.com HEAP for the Undercliff. INTRODUCTION This HEAP Area has been defined on the basis of geology, topography, land use and settlement patterns which differentiate it from other HEAP areas. This document identifies essential characteristics of the Undercliff as its geomorphology and rugged landslip areas, its archaeological potential, its 19 th century cottages ornés /marine villas and their grounds, and the Victorian seaside resort character of Ventnor. The Area has a highly distinctive character with an inner cliff towering above a landscape (now partly wooded) demarcated by stone boundary walls. The most significant features of this historic landscape, the most important forces for change and key management issues are considered. Actions particularly relevant to this Area are identified from those listed in the Isle of Wight HEAP Aims, Objectives and Actions. ANALYSIS AND ASSESSMENT Location, Geology and Topography • The Undercliff is identified as a discrete Landscape Character Type in the Isle of Wight AONB Management Plan (2004, 132). • The Area lies to the south of the South Wight Downland , from which it is separated by vertical cliffs forming a geological succession from Ferrugunious Sands through Sandrock, Carstone, Gault Clay, Upper Greensand, Chert Beds and Lower Chalk (Hutchinson 1987, Fig. 6). o The zone between the inner cliff and coastal cliff is a landslip area o This landslip is caused by groundwater lubrication of slip planes within the Gault Clays and Sandrock Beds. -

Name of Deceased

Date before which Name of Deceased Address, description and date of death of Names, addresses and descriptions of Persons, to .whom notices, of claims are to be notices of claims (Surname first) Deceased given and names, in parentheses, of Personal Representatives to be given CLARKE, Robert Albert... 27 Monks Rise, Welwyn Garden City, Hert-. Midland Bank Trust Company Limited, Leet. Court,-15 King Street, Watford, 15th October J980 fordshire* Company Director. 5th June Hertfordshire WD1 8BN. (Midland Bank Trust Company Limited and (124) 1980. Marguerite Adelaide Clarke.) ASHW.ORTH, George 26 Thomas Street, Lincoln. 15th July 1980. Anthony T. Clark & Co., 5 Cornhill, Lincoln, Solicitors. (George Needham) ... 6th October 1980 (125) i] FLANIGAN, Eva Mary ... St. Raphaels, 32 Orchard Road, Bromley,: Lloyds Bank Limited, Croydon Trust Branch, Prudential House, Wellesley Road, 6th October 1980 Kent, Spinster. 17th May 1980. Croydon CR9 2DH. (127) MclANNET, Lilian Hester "Galloway," 15 Thorn Road, Catfield, Nor- Howard Pollok & Webb, 34 Prince of Wales Road, Norwich, Norfolk NR1 1LQ. 15th October 1980 • folk, Spinster. 23rd July 1980. (Christopher Alan Colborne.) • . • . - '- • (128) WATTS, Robert James... 19 Tennyson Road, Cowes, Isle of Wight Damant & Sons, 67 High Street, Cowes, Isle of Wight (GL), Solicitors. (Susan 18th October 1980 19th May 1980. .Marie Watts.) • . • (129) HALL, Ethelina ..; Longrove Hospital, Halton Lane, Epsom, Sur- Rose & Birn, 137-143 Stoke Newington High Street, London N16 OPA. (Noel 6th October 1980 rey, formerly of 274 Amhurst Road N.16, Francis Hall.) (130) Spinster. 24th October 1975. EADY, Meryl Ruth Vernons House, Northaw, Potters Bar, Hert- Barclays Bank Trust Company Limited, Luton Area Office, P.O. -

Patterns of Movement in the Ventnor Landslide Complex, Isle of Wight, Southern England --Manuscript Draft

Landslides Patterns of movement in the Ventnor landslide complex, Isle of Wight, southern England --Manuscript Draft-- Manuscript Number: LASL-D-14-00028R1 Full Title: Patterns of movement in the Ventnor landslide complex, Isle of Wight, southern England Article Type: Original Paper Corresponding Author: Jonathan Martin Carey, Ph.D GNS Science Avalon, Lower Hutt NEW ZEALAND Corresponding Author Secondary Information: Corresponding Author's Institution: GNS Science Corresponding Author's Secondary Institution: First Author: Jonathan Martin Carey, Ph.D First Author Secondary Information: Order of Authors: Jonathan Martin Carey, Ph.D Roger Moore, PhD David Neil Petley, PhD Order of Authors Secondary Information: Abstract: The patterns of ground movement were monitored within a large, deep-seated landslide complex at Ventnor in southern England, between May 1998 and June 2002 using automated crackmeters, settlement cells and vibrating wire piezometers. It was found that the landslide maintains a state of marginal instability, such that it is subject to continual very slow deformation. Movement is primarily on a low-angled basal shear surface at >90 metres depth. The movement record shows a series of distinct deformation patterns that vary as groundwater conditions change. Continuous slow deformation occurs across the landslide complex at rates of between 5 - 10 mm per year. The background pattern of movement does not appear to correlate with local porewater pressure. Periods of more rapid movement (reaching up to c. 34 mm per year during the monitoring period) were associated with a period of elevated groundwater, although the relationship between movement rate and porewater pressure was complex. The patterns of movement and the landslide geometry suggest that the likelihood of a rapid, catastrophic failure is low. -

To Download the Document 'LAF Minutes 07

Minutes & Information resulting from – Meeting 64 1st Newport Scout Hall, Woodbine Close, Newport Thursday 7th March 2019 Present at the meeting Forum Members: Others & Observers: Mark Earp - Chairman Jennine Gardiner-IWC PROW (LAF Secretary) Alec Lawson David Howarth – Observer / IWRA Steve Darch Helena Hewston – Observer / Shalfleet P/C Cllr Paul Fuller Diana Conyers - Ryde T/C John Gurney-Champion John Brownscombe – National Trust Tricia Merrifield Darrel Clarke - IWC Cllr John Hobart Mick Lyons –Havenstreet & Ashey PC Richard Grogan Cllr Steve Hastings John Heather Clare Bennett - CLA Mike Slater Gillian Belben – Gatcombe & Chillerton P/C Penny Edwards 1. Apologies Received, Confirmation of the Minutes of previous meeting, declarations of interest & introductions. Apologies: Stephen Cockett, Geoff Brodie, Jan Brooks, Mike Greenslade, Hugh Walding Confirmation – Done & minutes signed as a true copy Decelerations - None 2. Updates to tasks / matters arising from meeting 6 December 2018 Bus Stops – Mark Earp and a team of four inspected as many rural bus stops as they could. It was felt that by and large these were pretty good but a few do need improvement. All bus stops had a post and a current timetable. There had been grant out for sustainable travel called the “Innovation fund” Mark wondered if anyone had applied for concreate pads, to be funded, at any of the rural bus stop locations? The General Manager for Southern Vectis Mr Richard Tyldsley has been invited to the next LAF meeting. Prior to this LAF members / guests should take time to look at the rural bus stop locations in their areas and using their local knowledge have given feedback to the LAF of any unsafe or redundant ones. -

HEAP for Isle of Wight Rural Settlement

Isle of Wight Parks, Gardens & Other Designed Landscapes Historic Environment Action Plan Isle of Wight Gardens Trust: March 2015 2 Foreword The Isle of Wight landscape is recognised as a source of inspiration for the picturesque movement in tourism, art, literature and taste from the late 18th century but the particular significance of designed landscapes (parks and gardens) in this cultural movement is perhaps less widely appreciated. Evidence for ‘picturesque gardens’ still survives on the ground, particularly in the Undercliff. There is also evidence for many other types of designed landscapes including early gardens, landscape parks, 19th century town and suburban gardens and gardens of more recent date. In the 19th century the variety of the Island’s topography and the richness of its scenery, ranging from gentle cultivated landscapes to the picturesque and the sublime with views over both land and sea, resulted in the Isle of Wight being referred to as the ‘Garden of England’ or ‘Garden Isle’. Designed landscapes of all types have played a significant part in shaping the Island’s overall landscape character to the present day even where surviving design elements are fragmentary. Equally, it can be seen that various natural components of the Island’s landscape, in particular downland and coastal scenery, have been key influences on many of the designed landscapes which will be explored in this Historic Environment Action Plan (HEAP). It is therefore fitting that the HEAP is being prepared by the Isle of Wight Gardens Trust as part of the East Wight Landscape Partnership’s Down to the Coast Project, particularly since well over half of all the designed landscapes recorded on the Gardens Trust database fall within or adjacent to the project area. -

The Undercliff of the Isle of Wight

cover.qxp 13/08/2007 11:40 Page 1 The Undercliff of the Isle of Wight Aguide to managing ground instability managing ground instablity part 1.qxp 13/08/2007 10:39 Page 1 The Undercliff of the Isle of Wight Aguide to managing ground instability Dr Robin McInnes, OBE Centre for the Coastal Environment Isle of Wight Council United Kingdom managing ground instablity part 1.qxp 13/08/2007 10:39 Page 2 Acknowledgements About this guide This guide has been prepared by the Isle of Wight Council's Centre for the Coastal Environment to promote sustainable management of ground instability problems within the Undercliff of the Isle of Wight. This guidance has been developed following a series of studies and investigations undertaken since 1987. The work of the following individuals, who have contributed to our current knowledge on this subject, is gratefully acknowledged: Professor E Bromhead, Dr D Brook OBE, Professor D Brunsden OBE, Dr M Chandler, Dr A R Clark, Dr J Doornkamp, Professor J N Hutchinson, Dr E M Lee, Dr B Marker OBE and Dr R Moore. The assistance of Halcrow with the preparation of this publication is gratefully acknowledged. Photo credits Elaine David Studio: 40; High-Point Rendel: 48; IW Centre for the Coastal Environment: 14 top, 19, 20 top, 23, 31 bottom, 41, 42, 47, 50, 51, 55, 56, 62, 67; Dr R McInnes: 14 bottom, 16, 17, 37; Wight Light Gallery, Ventnor: covers and title pages, 4, 6, 16/17 (background), 30, 31, 32, 43. Copyright © Centre for the Coastal Environment, Isle of Wight Council, August 2007. -

This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from the King's Research Portal At

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Late-devensian and flandrian palaeoecological studies in the Isle of Wight. Scaife, R. G The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 08. Oct. 2021 LATE-OEVENSIANAIDFLAN)RIAN PALAEOECOLOGICAL STUDIESIN THE ISLE OF WIGHT ROBERTGORDON SCAIFE VOLUME2 0 THESIS SUBMITTEDFOR THE DEGREEOF DOCTOROF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENTOF GEOGRAPHY KING'S COLLEGE,UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 1980 'ý y \ 4. -

Parish Plans Biodiversity Project

Parish Biodiversity Audit for Beer Consultation draft – April 2010 Anne Harvey Report commissioned by Devon County Council Data supplied by the Devon Biodiversity Records Centre Contents INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... 4 DESIGNATED SITES .............................................................................................................................. 6 SITES OF SPECIAL SCIENTIFIC INTEREST ............................................................................................ 6 Sidmouth to Beer Coast SSSI ...................................................................................................... 6 Beer Quarry and Caves SSSI ...................................................................................................... 9 SPECIAL AREAS OF CONSERVATION .................................................................................................. 10 Sidmouth to West Bay Special Area of Conservation ............................................................ 10 Beer Quarry and Caves Special Area of Conservation .......................................................... 10 Poole Bay to Lyme Bay Reefs draft Special Area of Conservation ...................................... 11 COUNTY WILDLIFE SITES ................................................................................................................... 11 Beer Quarry and Caves County Wildlife Site .......................................................................... -

South West Coast Path: Seaton to Lyme Regis Via the Undercliff Walk

02/05/2020 South West Coast Path: Seaton to Lyme Regis via the Undercliff walk - SWC Saturday Walkers Club www.walkingclub.org.uk South West Coast Path: Seaton to Lyme Regis via the Undercliff walk Jungle like walk through the Axmouth / Lyme Regis undercliff, with sea views at the start and finish Length 6.7 miles (10.8 km) Toughness 4 out of 10 (6 when wet) with 1,350 ft (400 m) of ascent - 1 climb at the start then continuous small ups and downs over well maintained paths (but muddy and slippery path after wet weather). OS Maps OS Explorer 156 Walk This interesting walk explores the Axmouth to Lyme Regis undercliff - an almost jungle like area of overgrown vegetation Notes created by an 1839 landslip. While part of the South West Coast Path (SWCP), this is not a cliff top walk - there are sea views only at the start and finish. On Christmas Day 1839, a 5km x 1km x 200m section of cliff collapsed and slid downhill to create the undercliff. The area is still active, and a now a 6km long, and up to 1km wide 'undercliff' has formed with dense vegetation. At first the undercliff was farmed, but now it is a National Nature Reserve full of self-seeded plants and trees. With the reduction in the rabbit population due to myxomatosis, a lush vegation has formed, with a dense jungle of ferns, bracken, wild garlic and ash (trees). Sadly, English Nature is removing the non-native tropical plants that came from a former garden in the area. -

Isle of Wight Council Brownfield Land Register – Part 1 Maps

Isle of Wight Council Brownfield Land Register – Part 1 Maps - December 2018 Isle of Wight Council Brownfield Register Maps 2018 2 Isle of Wight Council Brownfield Register Maps 2018 1. Introduction 1.1. In 2017 a new duty was placed on local planning authorities to prepare, maintain and publish a register of previously developed land (brownfield land) which is suitable for residential development. The register had to be published by 31 December 2017 and should be reviewed at least once each year. 1.2. The register, known as the Brownfield Land Register comprises a standard set of information, prescribed by the Government that will be kept up-to-date, and made publicly available. The purpose of the register is to provide certainty for developers and communities and encourage investment in local areas. The registers will then be used to monitor the Government’s commitment to the delivery of brownfield sites. 1.3. The register must be kept in two parts: 1.3.1 Part 1 will include all sites which meet the definition of previously developed land1 and are 0.25 hectares or more in size or capable of accommodating at least 5 dwellings. They must also meet the Government's criteria, set out in paragraph (1) of Regulation 42 setting out that sites must be suitable, available and achievable for residential development. 1.3.2 Part 2 allows the council to select sites from Part 1 and grant Permission in Principle (PIP) for housing-led development, after undertaking necessary requirements for publicity, notification and consultation. More information can be found in the National Planning Practice Guidance 1.3. -

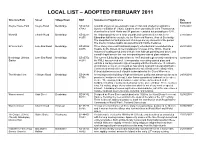

Local List – Adopted February 2011

LOCAL LIST – ADOPTED FEBRUARY 2011 Structure/Park Street Village/Town NGR Statement of Significance Date Reviewed Steyne House Park Steyne Road Bembridge SZ 64359 Grounds shown on Greenwood's map of 1826 and shaded on Ordnance 18/05/2001 87183 Survey 1st Edition 6" (1826). Gardens, then owned by Sir John Thorneycroft, described in a list of Hants and IW gardens - undated but probably pre-1914. Westhill Church Road Bembridge SZ 64277 An elegant property set in large grounds and constructed in 1906 in the 27/07/2007 88255 Edwardian half timbered style, for the Reverend Francis, Vicar of Bembridge. The steep tiled roof and prominent chimneys are key elements of the period. The interior includes quality oak panelling and marble fireplaces. St Veronica’s Lane End Road Bembridge SZ 65582 Three storey stone built traditional property extended and remodelled into a 25/01/2008 88075 hospice by the Sisters of the Compassion of Jesus in the 1930’s. Internal features of quality period detail include linen fold oak panelling and doors, and a small chapel area to the rear incorporating two stained glass windows. Bembridge Lifeboat Lane End Road Bembridge SZ 65752 The current ILB building dates back to 1867 and although recently extended by 02/06/2008 Station 88249 the RNLI, has survived well. It incorporates interesting stained glass and exhibits a low key domestic style in keeping with the streetscene. It relates to an important series of events and so has strong local and cultural significance. Constructed shortly after a shipping disaster specifically as the village's first lifeboat station as a result of public subscription by the City of Worcester. -

BULLETIN Feb 09

February 2009 Issue no.51 Bulletin Established 1919 www.iwnhas.org Contents Page(s) Page(s) President`s Address 1-2 Saxon Reburials at Shalfleet 10-11 Natural History Records 2 Invaders at Bonchurch 11 Country Notes 3-4 New Antiquarians 12-13 Brading Big Dig 4-5 General Meetings 13-22 Andy`s Notes 5-7 Section Meetings 22-34 Society Library 7 Membership Secretaries` Notes 34 Delian`s Archaeological Epistle 7-9 White Form of Garden Snail 9-10 President`s Address On Friday 10 th October 2008 a large and varied gathering met at Northwood House for a very special reason. We were attending the launch of HEAP, an unfortunate acronym, which still makes me think of garden rubbish. However, when the letters are opened up we find The Isle of Wight Historic Environ- ment Action Plan, a title which encompasses the historic landscape of the Island, the environment in which we live today and the future which we are bound to protect. It extends the work already being un- dertaken by the Island Biodiversity Action Plan, a little known but invaluable structure, which has al- ready been at work for ten years. This body brings together the diverse groups, national and local, whose concern is with the habitats and species which are part of our living landscape. The HEAP will do much the same at a local level for the landscape of the Island, the villages, towns, standing monuments which take us from the Stone Age to the present day and, most importantly, the agricultural landscape which is particularly vulnerable to intrusion and sometimes alarming change.