Roman Isle of Wight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

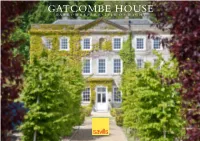

Gatcombe House G a T C O M B E P a R K • I S L E O F W I G H T Gatcombe House Gatcombe Park • Isle of Wight

GATCOMBE HOUSE G A T C O M B E P A R K • I S L E O F W I G H T GATCOMBE HOUSE GATCOMBE PARK • ISLE OF WIGHT Newport: 3 miles • Cowes 9 miles • Fishbourne Ferry 9.5 miles (Portsmouth Harbour from 45 mins) Battersea Heliport 35 mins (All mileages and time approximate) An exemplar of Georgian elegance ACCOMMODATION Entrance porch • Reception hall • Drawing room • Dining room • Billiard room • Study • Office Sitting room • Gymnasium • Kitchen/breakfast room • Preparation kitchen • Staircase hall Utility room • Cloakroom • Extensive cellars Main bedroom with adjoining bathroom and dressing room with separate loo Two further bedrooms with adjoining bathrooms • Additional six bedrooms and bathrooms One bedroom staff flat • Studio The Coach House: Entrance hall • Kitchen/living room • Sitting room • Utility room • Loo Artist’s studio • Two studies • Main bedroom with adjoining bathroom Three further bedrooms and bathroom • Garden Stable Cottage: Entrance hall • Kitchen/living room • Main bedroom with adjoining bathroom Two further bedrooms and bathroom • Loo • Garden Formal gardens and lawns • Rose garden • Parkland • Pastureland • Woodland Walled courtyard with greenhouse and herb borders • Ornamental lake • Specimen and ornamental trees Grade II listed bridge • Swimming Pool • Pavilion • Tennis court • Garaging and outbuildings Extensive agricultural buildings with adjoining field In all about 48 acres (19.35 hectares) George Nares Steven Moore Savills Country Department Savills Winchester [email protected] [email protected] 020 7016 3822 01962 834 010 Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the text HISTORY Gatcombe Park estate has an exciting and colourful history with records preceding the Norman Conquest and the village of Gatcombe is listed in the Domesday Book. -

STENBURY FEDERATION Interim Executive Headteacher: Mr M Snow Chair of Governors: Mrs D Barker [email protected]

STENBURY FEDERATION Interim Executive Headteacher: Mr M Snow Chair of Governors: Mrs D Barker [email protected] Chillerton & Rookley Primary Godshill Primary Main Road, Chillerton School Road, Godshill Isle of Wight, PO30 3EP Isle of Wight, PO38 3HJ Tel. 01983 721207 Tel. 01983 840246 [email protected] [email protected] Wednesday 14th July 2021 Re: Godshill Class Structure for September 2021 Dear Parents and Carers, We are really looking forward to the end of term and a well-earned rest. Many of you will be wanting to know which classes and teachers your children will be having. The class structure for September will be: Class Class Name Teacher / Lead Support Staff Entrance to School Nursery Bembridge Windmill Marie Seaman Jim Palmer Nursery Gate Kate McKenzie Alana Monroe Reception Calbourne Mill Mrs Polly Smith Dawn Sargent Reception Gate – Lizzie Burden Car park Year 1/2 Osbourne House Miss Kirsty Hart Wendy Whitewood Main Entrance Year 2/3 The Needles Mr Conner Knight Lisa Young Main Entrance Brogan Bodman Year 4/5 Carisbrooke Castle Mrs Westhorpe and Jodie Wendes Car park side Mrs Tombleson entrance Year 5 Yarmouth Castle Mr Tim Smith Chantelle De’ath Steps side of school Lauren Shaw-Yates Year 6 St Catherine’s Mrs Boakes Danny Chapman Steps side of school Oratory Any pupils that are in the mixed class of Year 1/2 or 4/5 that are in Year 2 or 5 will be contacted individually by the school. School will start at 8:45am for all pupils. School finishes for all pupils at 3:00pm, except for Reception, who will finish at 2:55pm. -

Three Early Anglo-Saxon Metalwork Finds from the Isle of Wight, 1993-6

Proc. Hampshire Field Club Archaeol. Soc. 53, 1998,109-119 (Hampshire Studies 1998) THREE EARLY ANGLO-SAXON METALWORK FINDS FROM THE ISLE OF WIGHT, 1993-6 .ByMARKSTEDMAN ABSTRACT A Cruciform Brooch, a Disc Brooch and a Frank- Description ish/Merovingian Bronze Bowl are discussed in the light of Though incomplete in form the object under ex the relationship between Late Roman villas and Early amination has a grey green patina which exhibits a Anglo-Saxon cemeteries and settlements. TheirJindspots arehig h degree of scratch and wear. However the also commented upon in regard to the suggested reuse of artefact fortunately seems free of any active corro Bronze Age download barrow cemeteries as properly sion. In its damaged state, from the top knob- boundary markers. The Island's Early Anglo-Saxon settle- headed terminal to the break in the artefact's 'bow' ment,focusing upon downland springlmes, is also discussed. spine, it measures 47.5 mm in length. The object seems to have suffered damage in antiquity, since the breaks in the artefact are not clean. Its bow 'spine' is gendy angled within the front piece, yet A CRUCIFORM BROOCH FROM the foot plate is missing below the break. It is of BLOODSTONE COPSE, solid construction, rather than being hollow in EAGLEHEAD DOWN, NEAR RYDE form, which could suggest that the artefact was an (Figsl&2) earlier variant or of a localised type (Eagles 1993, 133). On 9 August, 1995, a Mr Beeney brought a series The foot plate of the brooch is missing below of artefacts to the Isle of Wight Archaeological the break in the bow, which in turn has been Centre for identification purposes. -

I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE I provided by NERC Open Research Archive I BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY I MARINE REPORT SERIES TECHNICAL REPORT WB/95/35 I I I I I I BGS TECHNICAL REPORT WB/95/35 The Wight 1:250 OOO-scale Solid Geology sheet I (2nd Edition) by I I J Andrews I' I Geographical index Wight, English Channel I Subject index: Solid Geology I Production of report was funded by: Science budget I Bibliographic reference: Andrews, U. 1995. The Wight 1:250 OOO-scale Solid Geology sheet (2nd Edition) I British Geological Survey Technical Report WB/95/35 British Geological Survey Tel: 0131 667 1000 I Marine Geology & Operations Group Fax: 0131 6684140 Murchison House Tlx: 727343 West Mains Road I Edinburgh EH93LA I NERC Copyright 1995 I This report has been generated from a scanned image of the document with any blank pages removed at the scanning stage. Please be aware that the pagination and scales of diagrams or maps in the resulting report may not appear as in the original I I CONTENTS Page I' 1. INTRODUCTION 1 I 2. DATASET 2 'II 2.1 Onshore 2 2.2 Offshore 4 I 3. MAP REVISION 9 I 3.1 Amendments 9 3.2 Additional features 10 I 4. GEOLOGY 13 4.1 Structural history of the Wessex-Channel Basin 13 I 4.2 Stratigraphy 14 I 5. HYDROCARBONS 23 I 6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 24 'I 7. REFERENCES AND SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY 25 I FIGURES I Figure 1 Location of the GSI deep-seismic survey used during map production I Permo-Triassic isopach map Figure 2 I I I I I I I I I 1. -

Ryde Esplanade

17 May until late Summer 2021 BUS REPLACEMENT SERVICE , oad t sheaf Inn enue recourt splanade Av fo on Stree ading andown Ryde E Ryde Br S Lake Shanklin Bus Station St Johns R The Wheat The Broadway The Shops Station Monkt Station Ryde Pier Head by Jubilee Place Isle of Wight Steam Railway Sandown Sandown Bay Revised Timetable – ReplacementGrove R oadBus ServiceAcademy Monday Ryde Pier 17 Head May - untilRyde Esplanadelate Summer - subject 2021 to Wightlink services operating RydeRyde Pier Esplanade Head to -Ryde Ryde Esplanade St Johns Road - Brading - Sandown - Lake - Shanklin RydeBuses Esplanaderun to the Isle to of ShanklinWight Steam Railway from Ryde Bus Station on the hour between 1000 - 1600 SuX SuX SuX SuX Ryde Pier Head 0549 0607 0628 0636 0649 0707 0728 0736 0749 0807 0828 0836 0849 0907 Ryde Esplanade Bus Station 0552 0610 0631 0639 0652 0710 0731 0739 0752 0810 0831 0839 0852 0910 Ryde Pier Head 0928 0936 0949 1007 1028 1036 1049 1107 1128 1136 1149 1207 1228 1236 Ryde Esplanade Bus Station 0931 0939 0952 1010 1031 1039 1052 1110 1131 1139 1152 1210 1231 1239 Ryde Pier Head 1249 1307 1328 1336 1349 1407 1428 1436 1449 1507 1528 1536 1549 1607 Ryde Esplanade Bus Station 1252 1310 1331 1339 1352 1410 1431 1439 1452 1510 1531 1539 1552 1610 Ryde Pier Head 1628 1636 1649 1707 1728 1736 1749 1807 1828 1836 1849 1907 1928 1936 Ryde Esplanade Bus Station 1631 1639 1652 1710 1731 1739 1752 1810 1831 1839 1852 1910 1931 1939 Ryde Pier Head 1949 2007 2028 2036 2049 2128 2136 2149 2228 2236 2315 Ryde Esplanade Bus Station 1952 2010 -

The First Record of a Mammal from the Insect Limestone Is a Left Lower Incisor of the Rodent Isoptychus (NHMUK.PV.M45566) (Fig.3B)

Vertebrate remains from the Insect Limestone (latest Eocene), Isle of Wight, UK Hooker, J. J., Department of Earth Sciences, Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London, SW7 5BD, UK (corresponding author) Evans, S. E., Department of Cell and Developmental Biology, University College London, Anatomy Building, Gower Street, London, WC1E 6BT, UK Davis, P. G., c/o J. J. Hooker Running head: Insect Limestone vertebrates 1 Abstract A small fauna of vertebrates is recorded from the Insect Limestone, Bembridge Marls Member, Bouldnor Formation, late Priabonian, latest Eocene, of the Isle of Wight, UK. The taxa represented are teleost fishes, lizards including a scincoid, unidentified birds and the theridomyid rodent Isoptychus. The scincoid represents the youngest record of the group in the UK. Of particular note is the taphonomic interpretation based on the preservation of anatomical parts of land-based tetrapods that would have been most likely transported to the site of deposition by wind, namely bird feathers and pieces of shed lizard skin. These comprise the majority of the specimens and suggest that the dominant transport mechanism was wind. Keywords: Bembridge Marls – bird – feather – fish – lizard – mammal – rodent – Scincoidea – skin – Squamata – taphonomic – Theridomyidae 2 The Insect Limestone is a discrete bed of fine-grained, hard, muddy, freshwater to hypersaline limestone near the base of the Bembridge Marls Member of the Bouldnor Formation (Munt 2014; Ross & Self 2014). Its age is late Priabonian, thus latest Eocene (Hooker et al. 2009). Insect and plant remains are relatively common, whilst vertebrate remains are exceptionally rare and are limited to fragmentary skeletal elements of fish, lizard, bird and mammal, bird feathers and pieces of shed lizard skin. -

Havenstreet, Ashey & Haylands Population

Ward profile information packs: Havenstreet, Ashey & Haylands Population The information within this pack is designed to offer key data and information about this ward in a variety of subjects. It is one in a series of 39 packs produced by the Isle of Wight Council Business Intelligence Unit which cover all electoral wards. Population Havenstreet, Ashey Population Change & Haylands Isle of Wight Population (2011 Census) 3,613 138,265 The table below shows the population figures for % of the Island total 2.61% Havenstreet, Ashey & Haylands, Ryde Cluster and the Isle of Wight as a whole and how their populations Havenstreet, Ashey & Haylands Isle of Wight Males have changed since 2002 (using ONS mid-year 10% Age Males Females estimates). 0-4 8% 98 89 Havenstreet, 5-9 90 100 Ashey & Ryde Cluster Isle of Wight 6% 10-14 127 103 Haylands 15-19 118 103 Pop. % Pop. % Pop. % 4% 20-24 97 68 2002 3,360 34,345 134,038 % of Island % of Island population 25-29 81 81 2% 2003 3,423 +1.88 34,528 +0.53 135,073 +0.77 30-24 89 96 2004 3,403 -0.58 34,782 +0.74 136,409 +0.99 0% 35-39 113 95 40-44 114 147 2005 3,504 +2.97 35,051 +0.77 137,827 +1.04 45-49 125 168 2006 3,541 +1.06 35,115 +0.18 138,536 +0.51 Havenstreet, Ashey & Haylands Isle of Wight Females 50-54 118 135 2007 3,584 +1.21 35,398 +0.81 139,443 +0.65 10% 55-59 133 130 2008 3,577 -0.20 35,508 +0.31 140,158 +0.51 8% 60-64 131 130 2009 3,595 +0.50 35,504 -0.01 140,229 +0.05 65-69 110 131 2010 3,578 -0.47 35,728 +0.63 140,491 +0.19 6% 70-74 69 74 Source: ONS – Mid-Year Population Estimates 75-79 59 74 4% 80-84 36 58 In total between 2002 and 2010, the population of % of Island % of Island population 2% 85+ 33 90 Havenstreet, Ashey & Haylands had increased by Total 1,741 1,872 6.49%, Ryde Cluster had increased by 4.03% and the 0% Isle of Wight had increased by 4.81%. -

Historic Environment Action Plan West Wight Chalk Downland

Directorate of Community Services Director Sarah Mitchell Historic Environment Action Plan West Wight Chalk Downland Isle of Wight County Archaeology and Historic Environment Service October 2008 01983 823810 archaeology @iow.gov.uk Iwight.com HEAP for West Wight Chalk Downland. INTRODUCTION The West Wight Chalk Downland HEAP Area has been defined on the basis of geology, topography and historic landscape character. It forms the western half of a central chalk ridge that crosses the Isle of Wight, the eastern half having been defined as the East Wight Chalk Ridge . Another block of Chalk and Upper Greensand in the south of the Isle of Wight has been defined as the South Wight Downland . Obviously there are many similarities between these three HEAP Areas. However, each of the Areas occupies a particular geographical location and has a distinctive historic landscape character. This document identifies essential characteristics of the West Wight Chalk Downland . These include the large extent of unimproved chalk grassland, great time-depth, many archaeological features and historic settlement in the Bowcombe Valley. The Area is valued for its open access, its landscape and wide views and as a tranquil recreational area. Most of the land at the western end of this Area, from the Needles to Mottistone Down, is open access land belonging to the National Trust. Significant historic landscape features within this Area are identified within this document. The condition of these features and forces for change in the landscape are considered. Management issues are discussed and actions particularly relevant to this Area are identified from those listed in the Isle of Wight HEAP Aims, Objectives and Actions. -

461 I. Introduction. and Cardita Deltoidea +

Downloaded from http://jgslegacy.lyellcollection.org/ at University of Oregon on June 23, 2016 ON THE F~0CENE AI~D 0LI60OENE OF THE HAMPSHIRE BASIN. 461 45. On the RELATIONS of the EocEnE and OLIa0CEN~ STRATA in the HA~trSHIR~. BASlI~. By Prof. JoH~ W. JuDD, F.R.S., See. G.S. (Read April 26, 1882.) I. Introduction. SI~cx the publication of my paper "On the Oligocene Strata of the Hampshire Basin" *, I have been favoured with many valuable suggestions and criticisms from geologists, both in this and other countries ; and the time has now perhaps arrived when some of the interesting c!uestions thus raised may be discussed with advantage. The great object of my former memoir was to determine the age and relations of a series of marine beds which contain a highly interesting fauna--a fauna presenting the closest affinities with that of a well-defined system of strata very widely distributed in Central Europe. In framing his classification of the Hampshire Tertiaries, the late Prof. Edward Forbes gave no pIace t~ this important series of beds--a fact which does not seam t~ Iiave bt~ea Strfiiciently considered by those among my critics who h~ve ~mm'rea.r ~ay proposed modifi- cation of Forbes's classification as tmaecessary-ahd, therefore, un- warrantable. The history of the discovery of this i~tevestiug marine series does not appear to be generally known. The late Sir Charles Lycll spent his earliest years in the New Forest, residing at Bartley Lodge near Lyndhurst. At that time shelly marls appear to have been in great request among agriculturists, being employed by them as a manure on some of the poorer soils, like the similar materials of the French Fahluns and our own Crags. -

826 INDEX 1066 Country Walk 195 AA La Ronde

© Lonely Planet Publications 826 Index 1066 Country Walk 195 animals 85-7, see also birds, individual Cecil Higgins Art Gallery 266 ABBREVIATIONS animals Cheltenham Art Gallery & Museum A ACT Australian Capital books 86 256 A La RondeTerritory 378 internet resources 85 City Museum & Art Gallery 332 abbeys,NSW see New churches South & cathedrals Wales aquariums Dali Universe 127 Abbotsbury,NT Northern 311 Territory Aquarium of the Lakes 709 FACT 680 accommodationQld Queensland 787-90, 791, see Blue Planet Aquarium 674 Ferens Art Gallery 616 alsoSA individualSouth locations Australia Blue Reef Aquarium (Newquay) Graves Gallery 590 activitiesTas 790-2,Tasmania see also individual 401 Guildhall Art Gallery 123 activitiesVic Victoria Blue Reef Aquarium (Portsmouth) Hayward Gallery 127 AintreeWA FestivalWestern 683 Australia INDEX 286 Hereford Museum & Art Gallery 563 air travel Brighton Sea Life Centre 207 Hove Museum & Art Gallery 207 airlines 804 Deep, The 615 Ikon Gallery 534 airports 803-4 London Aquarium 127 Institute of Contemporary Art 118 tickets 804 National Marine Aquarium 384 Keswick Museum & Art Gallery 726 to/from England 803-5 National Sea Life Centre 534 Kettle’s Yard 433 within England 806 Oceanarium 299 Lady Lever Art Gallery 689 Albert Dock 680-1 Sea Life Centre & Marine Laing Art Gallery 749 Aldeburgh 453-5 Sanctuary 638 Leeds Art Gallery 594-5 Alfred the Great 37 archaeological sites, see also Roman Lowry 660 statues 239, 279 sites Manchester Art Gallery 658 All Souls College 228-9 Avebury 326-9, 327, 9 Mercer Art Gallery -

Planning and Infrastructure Services

PLANNING AND INFRASTRUCTURE SERVICES The following planning applications and appeals have been submitted to the Isle of Wight Council and can be viewed online www.iow.gov.uk/planning using the link labelled ‘Search planning applications made since February 2004’. Alternatively they can be viewed at Seaclose Offices, Fairlee Road, Newport, Isle of Wight, PO30 2QS. Office Hours: Monday – Thursday 8.30 am – 5.00 pm Friday 8.30 am – 4.30 pm Comments on the applications must be received within 21 days from the date of this press list, and comments for agricultural prior notification applications must be received within 7 days to ensure they be taken into account within the officer report. Comments on planning appeals must be received by the Planning Inspectorate within 5 weeks of the appeal start date (or 6 weeks in the case of an Enforcement Notice appeal). Details of how to comment on an appeal can be found (under the relevant LPA reference number) at www.iow.gov.uk/planning. For householder, advertisement consent or minor commercial (shop) applications, in the event of an appeal against a refusal of planning permission, representations made about the application will be sent to Planning Inspectorate, and there will be no further opportunity to comment at appeal stage. Should you wish to withdraw a representation made during such an application, it will be necessary to do so in writing within 4 weeks of the start of an appeal. All written representations relating to applications will be made available to view online. PLEASE NOTE THAT APPLICATIONS -

REAPPRAISAL of a COLLARED URN and OTHER POTTERY from BARROW 8, ASHEY DOWN, ISLE of WIGHT by DAVID J

REAPPRAISAL OF A COLLARED URN AND OTHER POTTERY FROM BARROW 8, ASHEY DOWN, ISLE OF WIGHT By DAVID J. TOMALIN INTRODUCTION IN 1969, excavations on Ashey Down revealed some 240 potsherds lying on the buried land surface beneath Barrow 8 and scattered in and beyond the surrounding ditch. Forty-six sherds are of similar fabric and 9 bear impressed decoration which has been described as 'short, wide, whipped, cord, maggots'. At first sight these sherds resemble some Late Neolithic pottery from beneath two other Island round barrows at Niton and Arreton Down (Dunning 1932, 198-210; Alexander and Ozanne i960, 276-281). In the Ashey Down excavation report in these Proceedings (Drewett 1972) the assemblage is reported as Neolithic and described as probably representing simple bag-shaped bowls. In 1973 the writer examined the Ashey Down material while preparing a catalogue at Carisbrooke Castle Museum. This article seeks to record new information showing that at present there is little evidence for Neolithic occupation on Ashey Down. THE BRONZE AGE POTTERY (FIG. 1) In the excavation report 12 sherds illustrate the pre-barrow material from the site and are conveniendy numbered 1-12 (Drewett, Fig. 25). In this article they are prefixed D. Most important are sherds D 1-9 which are here recognised as a single vessel, Fig. 1, no. 1, comprising some 46 fragments. The critical sherds are D5 (upside-down) and D 7, both of which form the overhanging portion of a collar. Breaks in the sherds had occurred flush with the overhang and these details seem to have been misinterpreted in the original study, apparently for a rather unusual reason.