A New Look at Paekche and Korean: Data from Nihon Shoki*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Man'yogana.Pdf (574.0Kb)

Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies http://journals.cambridge.org/BSO Additional services for Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here The origin of man'yogana John R. BENTLEY Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies / Volume 64 / Issue 01 / February 2001, pp 59 73 DOI: 10.1017/S0041977X01000040, Published online: 18 April 2001 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0041977X01000040 How to cite this article: John R. BENTLEY (2001). The origin of man'yogana. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 64, pp 5973 doi:10.1017/S0041977X01000040 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/BSO, IP address: 131.156.159.213 on 05 Mar 2013 The origin of man'yo:gana1 . Northern Illinois University 1. Introduction2 The origin of man'yo:gana, the phonetic writing system used by the Japanese who originally had no script, is shrouded in mystery and myth. There is even a tradition that prior to the importation of Chinese script, the Japanese had a native script of their own, known as jindai moji ( , age of the gods script). Christopher Seeley (1991: 3) suggests that by the late thirteenth century, Shoku nihongi, a compilation of various earlier commentaries on Nihon shoki (Japan's first official historical record, 720 ..), circulated the idea that Yamato3 had written script from the age of the gods, a mythical period when the deity Susanoo was believed by the Japanese court to have composed Japan's first poem, and the Sun goddess declared her son would rule the land below. -

Unexpected Nasal Consonants in Joseon-Era Korean Thomas

Unexpected Nasal Consonants in Joseon-Era Korean Thomas Darnell 17 April 2020 The diminutive suffixes -ngaji and -ngsengi are unique in contemporary Korean in that they both begin with the velar nasal consonant (/ŋ/) and seem to be of Korean origin. Surprisingly, they seem to share no direct genetic affiliation. But by reverse-engineering sound change involving the morpheme-initial velar nasal in the Ulsan dialect, I prove that the historical form of -aengi was actually maximally -ng; thus the suffixes -ngaji and -ngsaengi are related if we consider them to be concatenations of this diminutive suffix -ng and the suffixes -aji and -sengi. This is supported by the existence of words with the -aji suffix in which the initial velar nasal -ㅇ is absent and which have no semantic meaning of diminutiveness. 1. Introduction Korean is a language of contested linguistic origin spoken primarily on the Korean Peninsula in East Asia. There are approximately 77 million Korean speakers globally, though about 72 million of these speakers reside on the Korean peninsula (Eberhard et al.). Old Korean is the name given to the first attested stage of the Koreanic family, referring to the language spoken in the Silla kingdom, a small polity at the southeast end of the Korean peninsula. It is attested (at first quite sparsely) from the fifth century until the overthrow of the Silla state in the year 935 (Lee & Ramsey 2011: 48, 50, 55). Soon after that year, the geographic center of written Korean then moved to the capital of this conquering state, the Goryeo kingdom, located near present-day Seoul; this marks the beginning of Early Middle Korean (Lee & Ramsey: 50, 77). -

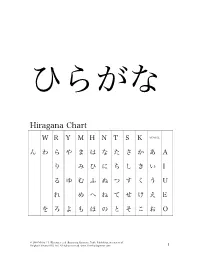

Hiragana Chart

ひらがな Hiragana Chart W R Y M H N T S K VOWEL ん わ ら や ま は な た さ か あ A り み ひ に ち し き い I る ゆ む ふ ぬ つ す く う U れ め へ ね て せ け え E を ろ よ も ほ の と そ こ お O © 2010 Michael L. Kluemper et al. Beginning Japanese, Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. All rights reserved. www.TimeForJapanese.com. 1 Beginning Japanese 名前: ________________________ 1-1 Hiragana Activity Book 日付: ___月 ___日 一、 Practice: あいうえお かきくけこ がぎぐげご O E U I A お え う い あ あ お え う い あ お う あ え い あ お え う い お う い あ お え あ KO KE KU KI KA こ け く き か か こ け く き か こ け く く き か か こ き き か こ こ け か け く く き き こ け か © 2010 Michael L. Kluemper et al. Beginning Japanese, Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. All rights reserved. www.TimeForJapanese.com. 2 GO GE GU GI GA ご げ ぐ ぎ が が ご げ ぐ ぎ が ご ご げ ぐ ぐ ぎ ぎ が が ご げ ぎ が ご ご げ が げ ぐ ぐ ぎ ぎ ご げ が 二、 Fill in each blank with the correct HIRAGANA. SE N SE I KI A RA NA MA E 1. -

Old Age in Pre-Nara and Nara Periods*

Old Age in Pre-Nara and Nara Periods by Susanne Formanek (Vienna) Demographic meaning of old age and age classes In trying to establish the demographic meaning of old age in the Pre-Nara and Nara Periods we learn from the surviving evidence that it was rare for people to reach an advanced age. It is likely that only 5 % or even less of all fifteen-years- olds in the Jômon Period could expect to live until the age of 50 or more. On the basis of life tables it can be seen that life expectancy, while being very low in all age classes, stayed at either virtually the same level or declined only very slowly after the age of 40 or 50; therefore the chances of living even longer after having attained that age were comparatively good.1 Very much the same structure but with improved overall mortality rates was apparently maintained till the Nara Period, where the koseki show persons of over 60 to account for 3 to 5 % of the population, a still small but by no means insignificant number, since about 40% of the population was made up by children under the age of 15. Thus the number of the aged was of no little importance among the adult popu- lation. Furthermore, having reached the age of 40 or 50, one had very good chances to live for another 20 or 30 years.2 This essay is a slightly improved version of a paper read at the Vth International Conference on Japanese Studies of the European Association for Japanese Studies in Durham, Septem- ber 1988. -

Proposal for a Korean Script Root Zone LGR 1 General Information

(internal doc. #: klgp220_101f_proposal_korean_lgr-25jan18-en_v103.doc) Proposal for a Korean Script Root Zone LGR LGR Version 1.0 Date: 2018-01-25 Document version: 1.03 Authors: Korean Script Generation Panel 1 General Information/ Overview/ Abstract The purpose of this document is to give an overview of the proposed Korean Script LGR in the XML format and the rationale behind the design decisions taken. It includes a discussion of relevant features of the script, the communities or languages using it, the process and methodology used and information on the contributors. The formal specification of the LGR can be found in the accompanying XML document below: • proposal-korean-lgr-25jan18-en.xml Labels for testing can be found in the accompanying text document below: • korean-test-labels-25jan18-en.txt In Section 3, we will see the background on Korean script (Hangul + Hanja) and principal language using it, i.e., Korean language. The overall development process and methodology will be reviewed in Section 4. The repertoire and variant groups in K-LGR will be discussed in Sections 5 and 6, respectively. In Section 7, Whole Label Evaluation Rules (WLE) will be described and then contributors for K-LGR are shown in Section 8. Several appendices are included with separate files. proposal-korean-lgr-25jan18-en 1 / 73 1/17 2 Script for which the LGR is proposed ISO 15924 Code: Kore ISO 15924 Key Number: 287 (= 286 + 500) ISO 15924 English Name: Korean (alias for Hangul + Han) Native name of the script: 한글 + 한자 Maximal Starting Repertoire (MSR) version: MSR-2 [241] Note. -

The Japanese Writing Systems, Script Reforms and the Eradication of the Kanji Writing System: Native Speakers’ Views Lovisa Österman

The Japanese writing systems, script reforms and the eradication of the Kanji writing system: native speakers’ views Lovisa Österman Lund University, Centre for Languages and Literature Bachelor’s Thesis Japanese B.A. Course (JAPK11 Spring term 2018) Supervisor: Shinichiro Ishihara Abstract This study aims to deduce what Japanese native speakers think of the Japanese writing systems, and in particular what native speakers’ opinions are concerning Kanji, the logographic writing system which consists of Chinese characters. The Japanese written language has something that most languages do not; namely a total of three writing systems. First, there is the Kana writing system, which consists of the two syllabaries: Hiragana and Katakana. The two syllabaries essentially figure the same way, but are used for different purposes. Secondly, there is the Rōmaji writing system, which is Japanese written using latin letters. And finally, there is the Kanji writing system. Learning this is often at first an exhausting task, because not only must one learn the two phonematic writing systems (Hiragana and Katakana), but to be able to properly read and write in Japanese, one should also learn how to read and write a great amount of logographic signs; namely the Kanji. For example, to be able to read and understand books or newspaper without using any aiding tools such as dictionaries, one would need to have learned the 2136 Jōyō Kanji (regular-use Chinese characters). With the twentieth century’s progress in technology, comparing with twenty years ago, in this day and age one could probably theoretically get by alright without knowing how to write Kanji by hand, seeing as we are writing less and less by hand and more by technological devices. -

KANA Response Live Organization Administration Tool Guide

This is the most recent version of this document provided by KANA Software, Inc. to Genesys, for the version of the KANA software products licensed for use with the Genesys eServices (Multimedia) products. Click here to access this document. KANA Response Live Organization Administration KANA Response Live Version 10 R2 February 2008 KANA Response Live Organization Administration All contents of this documentation are the property of KANA Software, Inc. (“KANA”) (and if relevant its third party licensors) and protected by United States and international copyright laws. All Rights Reserved. © 2008 KANA Software, Inc. Terms of Use: This software and documentation are provided solely pursuant to the terms of a license agreement between the user and KANA (the “Agreement”) and any use in violation of, or not pursuant to any such Agreement shall be deemed copyright infringement and a violation of KANA's rights in the software and documentation and the user consents to KANA's obtaining of injunctive relief precluding any further such use. KANA assumes no responsibility for any damage that may occur either directly or indirectly, or any consequential damages that may result from the use of this documentation or any KANA software product except as expressly provided in the Agreement, any use hereunder is on an as-is basis, without warranty of any kind, including without limitation the warranties of merchantability, fitness for a particular purpose, and non-infringement. Use, duplication, or disclosure by licensee of any materials provided by KANA is subject to restrictions as set forth in the Agreement. Information contained in this document is subject to change without notice and does not represent a commitment on the part of KANA. -

1. Introduction 2. Studies on Jeju and Efforts to Preserve It

An Endangered Language: Jeju Language Yeong-bong Kang Jeju National University 1. Introduction It has been a well-known fact that language is closely connected with both speaker's mind and its local culture. Cultural trait, one of the core properties of language, means that language reflects culture of the society at large. Even though Jeju language samchun 'uncle' is a variation of its standard Korean samchon, it is hard to say that samchun has the same dictionary definition of samchon, the brother of father, especially unmarried. In Jeju, if he/she is older than the speaker, everyone, regardless of his/her sex, can be samchun whether or not he/she is the speaker's relative. It means that Jeju language well reflects local culture and social aspects of Jeju. In other words, Jeju language reflects Jeju culture and society, and it reveals Jeju people's soul. This paper aims to investigate efforts to preserve Jeju language which reflect Jeju people's soul and cultures, processes which Jeju was included in the Atlas of languages in danger by UNESCO, and substantive approaches for preserving Jeju. 2. Studies on Jeju and efforts to preserve it There have been lots of studies on Jeju and efforts to preserve it by individuals, institutions, media, and etc. 2.1 Individual studies on Jeju language and efforts to preserve it Individual studies on Jeju language started with Japanese linguist Ogura Shinpei's Jeju Dialect in 1913. He also presented The Value of Jeju Dialect and Jeju Dialect: Cheong-gu Journal in 1924 and 1931 each. -

The Story of IZUMO KAGURA What Is Kagura? Distinguishing Features of Izumo Kagura

The Story of IZUMO KAGURA What is Kagura? Distinguishing Features of Izumo Kagura This ritual dance is performed to purify the kagura site, with the performer carrying a Since ancient times, people in Japan have believed torimono (prop) while remaining unmasked. Various props are carried while the dance is that gods inhabit everything in nature such as rocks and History of Izumo Kagura Shichiza performed without wearing any masks. The name shichiza is said to derive from the seven trees. Human beings embodied spirits that resonated The Shimane Prefecture is a region which boasts performance steps that comprise it, but these steps vary by region. and sympathized with nature, thus treasured its a flourishing, nationally renowned kagura scene, aesthetic beauty. with over 200 kagura groups currently active in the The word kagura is believed to refer to festive prefecture. Within Shimane Prefecture, the regions of rituals carried out at kamikura (the seats of gods), Izumo, Iwami, and Oki have their own unique style of and its meaning suggests a “place for calling out and kagura. calming of the gods.” The theory posits that the word Kagura of the Izumo region, known as Izumo kamikuragoto (activity for the seats of gods) was Kagura, is best characterized by three parts: shichiza, shortened to kankura, which subsequently became shikisanba, and shinno. kagura. Shihoken Salt—signifying cleanliness—is used In the first stage, four dancers hold bells and hei (staffs with Shiokiyome paper streamers), followed by swords in the second stage of Sada Shinno (a UNESCO Intangible Cultural (Salt Purification) to purify the site and the attendees. -

The Myth of the Goddess of the Undersea World and the Tale of Empress Jingu’S Subjugation of Silla

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1993 20/2-3 The Myth of the Goddess of the Undersea World and the Tale of Empress Jingu’s Subjugation of Silla Akima Toshio In prewar Japan, the mythical tale of Empress Jingii’s 神功皇后 conquest of the Korean kingdoms comprised an important part of elementary school history education, and was utilized to justify Japan5s coloniza tion of Korea. After the war the same story came to be interpreted by some Japanese historians—most prominently Egami Namio— as proof or the exact opposite, namely, as evidence of a conquest of Japan by a people of nomadic origin who came from Korea. This theory, known as the horse-rider theory, has found more than a few enthusiastic sup porters amone Korean historians and the Japanese reading public, as well as some Western scholars. There are also several Japanese spe cialists in Japanese history and Japan-Korea relations who have been influenced by the theory, although most have not accepted the idea (Egami himself started as a specialist in the history of northeast Asia).1 * The first draft of this essay was written during my fellowship with the International Research Center for Japanese Studies, and was read in a seminar organized by the institu tion on 31 January 199丄. 1 am indebted to all researchers at the center who participated in the seminar for their many valuable suggestions. I would also like to express my gratitude to Umehara Takeshi, the director general of the center, and Nakanism Susumu, also of the center, who made my research there possible. -

Depression What Is Depression? Can People with Depression Be Helped? • Depression Is a Very Common Problem

Depression What is depression? Can people with depression be helped? • Depression is a very common problem. Yes they can! Together, counselling and medication • We all have times in our lives when we feel have proven positive results. sad or down. • Usually sad feelings go away, but someone with depression may find that the sadness stays COUNSELLING Going for longer; they lose interest in things they usually counselling or talking therapy will enjoy and are left feeling low or very down for help. It is important that you attend a long time. all your sessions when referred; • Day to day life becomes difficult to manage. develop healthy coping skills to • Many adults will at some time experience manage your depression. symptoms of depression. How will I know if I have depression? In the last two weeks you have experienced the following: MEDICATION Anti-depressant • feel depressed or down most of the time; medication when prescribed • lose interest or pleasure in things you and taken as advised can usually enjoyed; shift depression. • sleep more or less than usual; • eat more or less than usual; • feel tired and hopeless; • think it will be better if you died or that you want to commit suicide; • feelings of guilt and worthlessness; SELF HELP Make small changes in • reduced self-esteem or self-confidence; or your life by doing things you used • reduced attention and concentration. to enjoy. Spend time with people around you and be more active. Join a support group and learn Causes of depression: self-help skills. • many stressors e.g. trauma, housing problems, unemployment, major change, becoming a parent; • ill-health; Focusing on your emotional, mental and physical Where can I find help? • history of depression in your family; wellbeing to improve your mood and reconnect At your local clinic or hospital • if you have a history of abuse or went through with your community. -

Frank's Do-It-Yourself Kana Cards V

Frank's do-it-yourself kana cards v. 1.0, 2000-08-07 Frank Stajano University of Cambridge and AT&T Laboratories Cambridge http://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/~fms27/ and http://www.uk.research.att.com/~fms/ This set of flash cards is meant to help you familiar cards and insist on the difficult part of き and さ with a separate stroke, become fluent in the use of the Japanese ones. unlike what happens in the fonts used in hiragana and katakana syllabaries. I made this document. I have followed the stroke it because I needed one myself and could The complete set consists of 10 double- counts of Henshall-Takagaki, even when not find it in the local bookshops (kanji sided sheets (20 printable pages) of 50 they seem weird for the shape of the char- cards were available, and I bought those; cards each, but you may choose to print acter as drawn on the card. but kana cards weren't); if it helps you too, smaller subsets as detailed below. Actu- so much the better. ally there are some blanks, so the total The easiest way to turn this document into number of cards is only 428 instead of 500. a set of cards is simply to print it (double The romanisation system chosen for these It would have been possible to fit them on sided of course!) and then cut each page cards is the Hepburn, which is the most 9 sheets instead of 10, but only by com- into cards with a ruler and a sharp blade.