Writing Javanese Script in HTML Using Unicode True Type Font and Jawatex

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ka И @И Ka M Л @Л Ga Н @Н Ga M М @М Nga О @О Ca П

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3319R L2/07-295R 2007-09-11 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation Международная организация по стандартизации Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Proposal for encoding the Javanese script in the UCS Source: Michael Everson, SEI (Universal Scripts Project) Status: Individual Contribution Action: For consideration by JTC1/SC2/WG2 and UTC Replaces: N3292 Date: 2007-09-11 1. Introduction. The Javanese script, or aksara Jawa, is used for writing the Javanese language, the native language of one of the peoples of Java, known locally as basa Jawa. It is a descendent of the ancient Brahmi script of India, and so has many similarities with modern scripts of South Asia and Southeast Asia which are also members of that family. The Javanese script is also used for writing Sanskrit, Jawa Kuna (a kind of Sanskritized Javanese), and Kawi, as well as the Sundanese language, also spoken on the island of Java, and the Sasak language, spoken on the island of Lombok. Javanese script was in current use in Java until about 1945; in 1928 Bahasa Indonesia was made the national language of Indonesia and its influence eclipsed that of other languages and their scripts. Traditional Javanese texts are written on palm leaves; books of these bound together are called lontar, a word which derives from ron ‘leaf’ and tal ‘palm’. 2.1. Consonant letters. Consonants have an inherent -a vowel sound. Consonants combine with following consonants in the usual Brahmic fashion: the inherent vowel is “killed” by the PANGKON, and the follow- ing consonant is subjoined or postfixed, often with a change in shape: §£ ndha = § NA + @¿ PANGKON + £ DA-MAHAPRANA; üù n. -

Proposal for a Gurmukhi Script Root Zone Label Generation Ruleset (LGR)

Proposal for a Gurmukhi Script Root Zone Label Generation Ruleset (LGR) LGR Version: 3.0 Date: 2019-04-22 Document version: 2.7 Authors: Neo-Brahmi Generation Panel [NBGP] 1. General Information/ Overview/ Abstract This document lays down the Label Generation Ruleset for Gurmukhi script. Three main components of the Gurmukhi Script LGR i.e. Code point repertoire, Variants and Whole Label Evaluation Rules have been described in detail here. All these components have been incorporated in a machine-readable format in the accompanying XML file named "proposal-gurmukhi-lgr-22apr19-en.xml". In addition, a document named “gurmukhi-test-labels-22apr19-en.txt” has been provided. It provides a list of labels which can produce variants as laid down in Section 6 of this document and it also provides valid and invalid labels as per the Whole Label Evaluation laid down in Section 7. 2. Script for which the LGR is proposed ISO 15924 Code: Guru ISO 15924 Key N°: 310 ISO 15924 English Name: Gurmukhi Latin transliteration of native script name: gurmukhī Native name of the script: ਗੁਰਮੁਖੀ Maximal Starting Repertoire [MSR] version: 4 1 3. Background on Script and Principal Languages Using It 3.1. The Evolution of the Script Like most of the North Indian writing systems, the Gurmukhi script is a descendant of the Brahmi script. The Proto-Gurmukhi letters evolved through the Gupta script from 4th to 8th century, followed by the Sharda script from 8th century onwards and finally adapted their archaic form in the Devasesha stage of the later Sharda script, dated between the 10th and 14th centuries. -

"9-41516)9? "9787:)4 ;7 -6+7,- )=1 16 ;0- & $

L2/20-256 "9-41516)9?"9787:)4;7-6+7,-)=116;0-&$ ᭛᭜᭛ <;079 ,1;?))?<"-9,)6)215-14,7;3755/5)14+75 40)5 <9=)6:)0140)56<9=)6:)0/5)14+75 );- ;0$-8;-5*-9 6;97,<+;176 ,=:#6L>H8G>EI>H6=>HIDG>86AG6=B>76H:9H8G>EI;DJC9>CK6G>DJH>CH8G>EI>DCH6C96GI:;68IHEGD9J8:97:IL::CI=: I=6C9I=: I=8:CIJGN>C>CHJA6G+DJI=:6HIH>6A6G<:EDGI>DCD;>IH8DGEJH>H;DJC9>C"6K67JI#6L>B6I:G>6AH =6K:6AHD7::C;DJC9>C+JB6IG6%6A6N(:C>CHJA66A>6C9I=:(=>A>EE>C:H,=:H8G>EI>H;G:FJ:CIAN6HHD8>6I:9L>I= I=:'A9"6K6C:H:A6C<J6<:7JIB6I:G>6AHLG>II:C>C+6CH@G>I'A9%6A6N'A96A>C:H:6C9'A9+JC96C:H:A6C<J6<: =6H6AHD7::C;DJC9>CI=:#6L>H8G>EIGDBI=:B>9I=8:CIJGNH>BEA:;JC8I>DC6A#6L>L6HL>9:ANJH:9IDG:8DG9 A6C9 <G6CIH GDN6A :9>8IH 6C9 H>B>A6G 8=6C8:GN 9D8JB:CIH ,DL6G9H I=: :C9 D; I=: ;>GHI B>AA:CC>JB I=: H8G>EI 7:86B:>C8G:6H>C<AN9:8DG6I>K:6C986AA><G6E=>89J:ID>IHJH:6HI=:B6>CK:=>8A:D;'A9"6K6C:H:A>I:G6GNA6C<J6<: L>I=ADC<A6HI>C<A:<68N>CI=:A>I:G6GNIG69>I>DCD;I=:BD9:GC"6K6C:H:6C96A>C:H:A6C<J6<:H$6I:G#6L>H=DLH B6CNK6G>6I>DCHDK:G6L>9:<:D<G6E=>89>HIG>7JI>DC'K:GI>B:I=:H:K6G>6CIH=6K::KDAK:9>G:8IANDG>C9>G:8IAN >CIDI=:B6CNBD9:GCG6=B>8H8G>EIHD;>CHJA6G+H>6HJ8=6H6A>C:H:6I6@"6K6C:H:$DCI6G6:I8 /=>A:I=:68I>K:JH:D;#6L>H8G>EI=6H7::CG:EA68:97NDI=:GH8G>EIHH>C8:I=: I=8:CIJGNI=:G:6G:6CJB7:GD; BD9:GC96N:CI=JH>6HIH6C98DBBJC>I>:HL=DJH:I=:H8G>EIID96N;DGDI=:GEJGEDH:HI=6C6C8>:CIG:EGD9J8I>DC ;DG:M6BEA:ID8=6I>CHD8>6A6EEA>86I>DC6C98G:6I:>B6<:EDHIH!CI=>HG:K>K6AINE:D;JH:I=:#6L>H8G>EIB6N7: JH:9IDLG>I:A6C<J6<:HI=6I6G:CDI;DJC9>C‘6JI=:CI>8’#6L>8DGEJHHJ8=6HI=:BD9:GC"6K6C:H:A6C<J6<:DG I=: !C9DC:H>6C A6C<J6<: H#6L>=6H CDI 7::C :C8D9:9>C I=: -C>8D9: N:I I=: -

Ahom Range: 11700–1174F

Ahom Range: 11700–1174F This file contains an excerpt from the character code tables and list of character names for The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 This file may be changed at any time without notice to reflect errata or other updates to the Unicode Standard. See https://www.unicode.org/errata/ for an up-to-date list of errata. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/ for access to a complete list of the latest character code charts. See https://www.unicode.org/charts/PDF/Unicode-14.0/ for charts showing only the characters added in Unicode 14.0. See https://www.unicode.org/Public/14.0.0/charts/ for a complete archived file of character code charts for Unicode 14.0. Disclaimer These charts are provided as the online reference to the character contents of the Unicode Standard, Version 14.0 but do not provide all the information needed to fully support individual scripts using the Unicode Standard. For a complete understanding of the use of the characters contained in this file, please consult the appropriate sections of The Unicode Standard, Version 14.0, online at https://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode14.0.0/, as well as Unicode Standard Annexes #9, #11, #14, #15, #24, #29, #31, #34, #38, #41, #42, #44, #45, and #50, the other Unicode Technical Reports and Standards, and the Unicode Character Database, which are available online. See https://www.unicode.org/ucd/ and https://www.unicode.org/reports/ A thorough understanding of the information contained in these additional sources is required for a successful implementation. -

An Introduction to Indic Scripts

An Introduction to Indic Scripts Richard Ishida W3C [email protected] HTML version: http://www.w3.org/2002/Talks/09-ri-indic/indic-paper.html PDF version: http://www.w3.org/2002/Talks/09-ri-indic/indic-paper.pdf Introduction This paper provides an introduction to the major Indic scripts used on the Indian mainland. Those addressed in this paper include specifically Bengali, Devanagari, Gujarati, Gurmukhi, Kannada, Malayalam, Oriya, Tamil, and Telugu. I have used XHTML encoded in UTF-8 for the base version of this paper. Most of the XHTML file can be viewed if you are running Windows XP with all associated Indic font and rendering support, and the Arial Unicode MS font. For examples that require complex rendering in scripts not yet supported by this configuration, such as Bengali, Oriya, and Malayalam, I have used non- Unicode fonts supplied with Gamma's Unitype. To view all fonts as intended without the above you can view the PDF file whose URL is given above. Although the Indic scripts are often described as similar, there is a large amount of variation at the detailed implementation level. To provide a detailed account of how each Indic script implements particular features on a letter by letter basis would require too much time and space for the task at hand. Nevertheless, despite the detail variations, the basic mechanisms are to a large extent the same, and at the general level there is a great deal of similarity between these scripts. It is certainly possible to structure a discussion of the relevant features along the same lines for each of the scripts in the set. -

Introduction to Old Javanese Language and Literature: a Kawi Prose Anthology

THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN CENTER FOR SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES THE MICHIGAN SERIES IN SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIAN LANGUAGES AND LINGUISTICS Editorial Board Alton L. Becker John K. Musgrave George B. Simmons Thomas R. Trautmann, chm. Ann Arbor, Michigan INTRODUCTION TO OLD JAVANESE LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE: A KAWI PROSE ANTHOLOGY Mary S. Zurbuchen Ann Arbor Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies The University of Michigan 1976 The Michigan Series in South and Southeast Asian Languages and Linguistics, 3 Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/ Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 76-16235 International Standard Book Number: 0-89148-053-6 Copyright 1976 by Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies The University of Michigan Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-0-89148-053-2 (paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12818-1 (ebook) ISBN 978-0-472-90218-7 (open access) The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ I made my song a coat Covered with embroideries Out of old mythologies.... "A Coat" W. B. Yeats Languages are more to us than systems of thought transference. They are invisible garments that drape themselves about our spirit and give a predetermined form to all its symbolic expression. When the expression is of unusual significance, we call it literature. "Language and Literature" Edward Sapir Contents Preface IX Pronounciation Guide X Vowel Sandhi xi Illustration of Scripts xii Kawi--an Introduction Language ancf History 1 Language and Its Forms 3 Language and Systems of Meaning 6 The Texts 10 Short Readings 13 Sentences 14 Paragraphs.. -

A Barrier to Indic-Language Implementation of Unicode Is the Perception That Encoding Order in Unicode Is Equivalent to Lingui

Issues in Indic Language Collation Issues in Indic Language Collation Cathy Wissink Program Manager, Windows Globalization Microsoft Corporation I. Introduction As the software market for India1 grows, so does the interest in developing products for this market, and Unicode is part of many vendors’ solutions. However, many software vendors see a barrier to implementing Unicode on products for the Indic-language market. This barrier is the perception that deficiencies in Unicode will keep software developers from creating products that are culturally and linguistically appropriate for the Indian market. This perception manifests itself in a number of ways, but one major concern that the Indic language community has voiced is the fact that the Unicode character encoding order is not appropriate for linguistic collation (or sorting). This belief that character encoding order in Unicode must be equivalent to linguistic collation of these same scripts and their respective languages is considered by some developers a blocking point to adoption of Unicode in the Indian market, and is indicative of the greater concern within the Indic-language community about the feasibility of Unicode for their scripts. This paper will demonstrate that this perceived barrier to Unicode adoption does not exist and that it is possible to provide properly globalized software for the Indic market with the current implementation of Unicode, using the example of Indic language collation. A brief history of Indic encodings will be given to set the stage for the current mentality regarding Unicode in the Indian market. The basics of linguistic collation and its application to Indic scripts will then be discussed, compared to encoding, and demonstrated as it exists on Windows XP. -

Representing Myanmar in Unicode Details and Examples Version 3

Representing Myanmar in Unicode Details and Examples Version 3 Martin Hosken1 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................2 Unicode 5.1 Model.....................................................................................................................................4 Advanced Issues.......................................................................................................................................11 Languages.................................................................................................................................................14 Burmese....................................................................................................................................................15 Old Burmese.............................................................................................................................................18 Sanskrit/Pali..............................................................................................................................................20 Mon...........................................................................................................................................................22 Sgaw Karen...............................................................................................................................................24 Western Pwo Karen..................................................................................................................................26 -

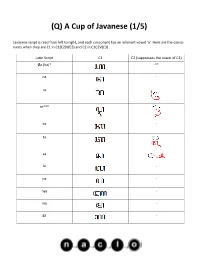

Q) a Cup of Javanese (1/5

(Q) A Cup of Javanese (1/5) Javanese script is read from left to right, and each consonant has an inherent vowel ‘a’. Here are the conso- nants when they are C1 in C1(C2)V(C3) and C2 in C1C2V(C3). Latin Script C1 C2 (suppresses the vowel of C1) Øa (ha)* -** na - ra re*** ka - ta sa la - pa - nya - ma - ga - (Q) A Cup of Javanese (2/5) Javanese script is read from left to right, and each consonant has an inherent vowel ‘a’. Here are the conso- nants when they are C1 in C1(C2)V(C3) and C2 in C1C2V(C3). Latin Script C1 C2 (suppresses the vowel of C1) ba nga - *The consonant is either ‘Ø’ (no consonant) or ‘h,’ but the problem contains only the former. **The ‘-’ means that the form exists, but not in this problem. ***The CV combination ‘re’ (historical remnant of /ɽ/) has its own special letters. ‘ng,’ ‘h,’ and ‘r’ must be C3 in (C1)(C2)VC3 before another C or at the end of a word. All other consonants after V must be C1 of the next syllable. If these consonants end a word, a ‘vowel suppressor’ must be added to suppress the inherent ‘a.’ Latin Script C3 -ng -h -r -C (vowel suppressor) Consonants can be modified to change the inherent vowel ‘a’ in C1(C2)V(C3). Latin Script V* e** (Q) A Cup of Javanese (3/5) Latin Script V* i é u o * If C2 is on the right side of C1, then ‘e,’ ‘i,’ and ‘u’ modify C2. -

The Wili Benchmark Dataset for Written Natural Language Identification

1 The WiLI benchmark dataset for written II. WRITTEN LANGUAGE BASICS language identification A language is a system of communication. This could be spoken language, written language or sign language. A spoken language Martin Thoma can have several forms of written language. For example, the E-Mail: [email protected] spoken Chinese language has at least three writing systems: Traditional Chinese characters, Simplified Chinese characters and Pinyin — the official romanization system for Standard Chinese. Abstract—This paper describes the WiLI-2018 benchmark dataset for monolingual written natural language identification. Languages evolve. New words like googling, television and WiLI-2018 is a publicly available,1 free of charge dataset of Internet get added, but written languages are also refactored. short text extracts from Wikipedia. It contains 1000 paragraphs For example, the German orthography reform of 1996 aimed at of 235 languages, totaling in 235 000 paragraphs. WiLI is a classification dataset: Given an unknown paragraph written in making the written language simpler. This means any system one dominant language, it has to be decided which language it which recognizes language and any benchmark needs to be is. adapted over time. Hence WiLI is versioned by year. Languages do not necessarily have only one name. According to Wikipedia, the Sranan language is also known as Sranan Tongo, Sranantongo, Surinaams, Surinamese, Surinamese Creole and I. INTRODUCTION Taki Taki. This makes ISO 369-3 valuable, but not all languages are represented in ISO 369-3. As ISO 369-3 uses combinations The identification of written natural language is a task which of 3 Latin letters and has 547 reserved combinations, it can appears often in web applications. -

-

Internationalized Domain Names-Hindi

Draft Policy Document For INTERNATIONALIZED DOMAIN NAMES Language: NEPALI 1 RECORD OF CHANGES *A - ADDED M - MODIFIED D - DELETED VERSION PAGES A* COMPLIANCE NUMBER DATE AFFECTED M TITLE OR BRIEF VERSION OF MAIN D DESCRIPTION POLICY DOCUMENT 1.0 20/11/09 Whole M Language Specific 1.5 Document Policy Document for NEPALI 1.1 22/11/2010 Page No 9, A Restriction rule 1.8 16, 19 added , Variant modified, ccTLD added 2 Table of Contents 1. AUGMENTED BACKUS-NAUR FORMALISM (ABNF) .......................................... 4 1.1 Declaration of variables ............................................................................................ 4 1.2 ABNF Operators ....................................................................................................... 4 1.3 The Vowel Sequence ................................................................................................. 4 1.4 Consonant Sequence ................................................................................................. 5 1.5 Sequence ................................................................................................................... 7 1.6 ABNF Applied to the IDN ........................................................................................ 7 2. RESTRICTION RULES ............................................................................................... 10 3. EXAMPLES ................................................................................................................. 12 5. NOMENCLATURAL DESCRIPTION TABLE OF NEPALI