The Superfluous and the Missing Metaphor in Il Postino

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

Ettore Scola, Humanist Des Italienischen Kinos ) 2 7 9 1 (

Ettore Scola, Humanist des italienischen Kinos ) 2 7 9 1 ( A T I V A I M A l l e D A T A r e S A l l e B ù I P A l u z n e t i e b r a h a e l r o D c n e S d i e e r b o a t l t o c E S e r o t t 47 e Ettore Scola (1931 –2016) ist einer der großen Meister Manfredi, Vittorio Gassmann, Stefania Sandrelli, Alberto des italienischen Films. Er gilt als legitimer Erbe von Sordi und Marcello Mastroianni. Sie verkörpern italieni - Roberto Rossellini, Vittorio de Sica und Federico Fellini sche Charaktertypen mit ihren typischen Merkmalen: und als wichtiger Impulsgeber für die nächste Genera - Der Kunst, sich in jeder Situation zu behelfen (arte di ar - tion. In Deutschland ist er jedoch bis heute weitgehend rangiarsi) sowie markanten Kontrasten zwischen unbekannt geblieben. Schein (Selbstsicherheit, Geltungsdrang, Hochmut) und Obwohl Ettore Scola ein juristisches Studium absolviert Sein (Schüchternheit, Engstirnigkeit, Opportunismus, hat, faszinierte ihn früh die Kinowelt. Bevor er eigene Feigheit). Ein menschliches Panoptikum aus gescheiter - Filme drehte, verfasste er mehr als fünfzig Drehbücher ten Angestellten, komplexbeladenen Strebern, Schnor - für Regisseure wie Luigi Zampa, Nanni Loy oder Mario rern, Schmarotzern, Träumern und Emanzen, die sich in Monicelli. Den Durchbruch als Regisseur mit einer sehr der neu entstehenden Welt der Freizeitangebote, der persönlichen Filmsprache und einer Vorliebe für sozial - freieren Sitten, des Wohlstands und des Konsums kritische Themen gelang ihm in den 1970er Jahren. bewegen – eine bunte comédie humaine, geprägt Über sein Konzept sagte Scola: »Mein Kino war nie ein durch das anekdotische, fragmentarische Erzählen und Kino der Phantasie, sondern immer eines der Beobach - das Zusammenspiel von dramatischen und grotesken tung«. -

Ferzan Özpetek Se Traslada a Italia En 1976 Para Estudiar Historia Del Cine En La Universidad De Roma

SALA FERNANDO REY 25, 26 y 27 de junio FERZAN MINE VAGANTI ÖZPETEK (TENGO ALGO QUE DECIROS) SOBRE EL DIRECTOR Nacido en Estambul, Ferzan Özpetek se traslada a Italia en 1976 para estudiar Historia del Cine en la Universidad de Roma. Realiza cursos de Historia del Arte y del Vestido en la Academia Navona, y cursos de Dirección en la Escuela de Arte Dramático "Silvio D´Amico". Es ciudadano italiano. Después de su colaboración con Julian Beck y el Living Theatre, comienza en 1982 su actividad como ayudante de dirección, primero con Massimo Troisi y posteriormente con Maurizio Ponzi. Como Director: Ferzan Özpetek ayudante de dirección ha trabajado además al Intérpretes: Lunetta Savino, Riccardo Scamarcio lado de otros directores como Ricky Tognazzi, Italia, 201 0- 11 7 min Lamberto Bava, Francesco Nuti, Sergio Citti, (V. O. S en castellano) - Formato: 35mm Giovanni Veronesi y Marco Risi. TODOS LOS PÚBLICOS * PREMIOS DAVID DI DONATELLO 2009: MEJOR ACTOR SECUNDARIO Y ACTRIZ SECUNDARIA. En 1996 coproduce y dirige su primera película, Hamam, el Baño Turco, seleccionada en el Las películas de Özpetek, cada vez más específicamente Quincena de Realizadores del Festival de italianas y menos interculturalistas, son en general suaves, Cannes. En 1999 Tilde Corsi y Gianni Romoli ternuristas, pero es su misma ligereza lo que les da un toque producen su segunda película, El Último personal, además de esa empatía emocional que se produce Harén, éxito de público y crítica y presentada cuando un personaje aparece aureolado de cierta verdad: en la Sección Una Cierta Mirada del Festival de Margherita Buy en El hada ignorante (2001), Giovanna Cannes. -

La Nascita Dell'eroe

Programma del CORSO 1) PARTE GENERALE - “Slide del Corso” - Gian Piero Brunetta, Guida alla storia del cinema italiano 1905-2003, Einaudi, pp. 127-303 (si trova su Feltrinelli a 8,99 e in ebook) 2) APPROFONDIMENTO (A SCELTA) DI DUE TRAI SEGUENTI LIBRI: - Mariapia Comand, Commedia all'italiana, Il Castoro - Ilaria A. De Pascalis, Commedia nell’Italia contemporanea, Il Castoro - Simone Isola, Cinegomorra. Luci e ombre sul nuovo cinema italiano, Sovera - Franco Montini/Vito Zagarrio, Istantanee sul cinema italiano, Rubbettino - Alberto Pezzotta, Il western italiano, Il Castoro - Alfredo Rossi, Elio Petri e il cinema politico italiano, Mimesis Edizioni - Giovanni Spagnoletti/Antonio V. Spera, Risate all'italiana. Il cinema di commedia dal secondo dopoguerra ad oggi, UniversItalia 3) CONOSCENZA DI 15 FILM RIGUARDANTI L’ARGOMENTO DEL CORSO Sugli autori o gli argomenti portati, possono (non devono) essere fatte delle tesine di circa 10.000 caratteri (spazi esclusi) che vanno consegnate SU CARTA (e non via email) IMPROROGABILMENTE ALMENO UNA SETTIMANA PRIMA DELL’ ESAME Previo accordo con il docente, si possono portare dei testi alternativi rispetto a quelli indicati INDIRIZZO SUL SITO: http://www.lettere.uniroma2.it/it/insegnamento/storia-del- cinema-italiano-2017-2018-laurea-triennale ELENCO DEI FILM PER L’ESAME (1) 1) Indagine su un cittadino al di sopra di ogni sospetto (1970) o Todo Modo (1976) di Elio Petri 2) Il conformista (1970) o L’ultimo imperatore (1987) di Bernardo Bertolucci 3) Cadaveri eccellenti (1976) di Francesco Rosi 4) Amici miei (1975) di Mario Monicelli 5) C’eravamo tanto amati (1974) o Una giornata particolare (1977) di Ettore Scola 6) Borotalco (1982) o Compagni di scuola (1984) di Carlo Verdone 7) Nuovo Cinema Paradiso (1988) o Una pura formalità (1994) di Giuseppe Tornatore. -

Italian Films (Updated April 2011)

Language Laboratory Film Collection Wagner College: Campus Hall 202 Italian Films (updated April 2011): Agata and the Storm/ Agata e la tempesta (2004) Silvio Soldini. Italy The pleasant life of middle-aged Agata (Licia Maglietta) -- owner of the most popular bookstore in town -- is turned topsy-turvy when she begins an uncertain affair with a man 13 years her junior (Claudio Santamaria). Meanwhile, life is equally turbulent for her brother, Gustavo (Emilio Solfrizzi), who discovers he was adopted and sets off to find his biological brother (Giuseppe Battiston) -- a married traveling salesman with a roving eye. Bicycle Thieves/ Ladri di biciclette (1948) Vittorio De Sica. Italy Widely considered a landmark Italian film, Vittorio De Sica's tale of a man who relies on his bicycle to do his job during Rome's post-World War II depression earned a special Oscar for its devastating power. The same day Antonio (Lamberto Maggiorani) gets his vehicle back from the pawnshop, someone steals it, prompting him to search the city in vain with his young son, Bruno (Enzo Staiola). Increasingly, he confronts a looming desperation. Big Deal on Madonna Street/ I soliti ignoti (1958) Mario Monicelli. Italy Director Mario Monicelli delivers this deft satire of the classic caper film Rififi, introducing a bungling group of amateurs -- including an ex-jockey (Carlo Pisacane), a former boxer (Vittorio Gassman) and an out-of-work photographer (Marcello Mastroianni). The crew plans a seemingly simple heist with a retired burglar (Totó), who serves as a consultant. But this Italian job is doomed from the start. Blow up (1966) Michelangelo Antonioni. -

![Bon Baisers De Sicile / Splendor De Ettore Scola / Cinema Paradiso De Guiseppe Tornatore]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0871/bon-baisers-de-sicile-splendor-de-ettore-scola-cinema-paradiso-de-guiseppe-tornatore-1260871.webp)

Bon Baisers De Sicile / Splendor De Ettore Scola / Cinema Paradiso De Guiseppe Tornatore]

Document generated on 09/29/2021 7:07 p.m. 24 images Bon baisers de Sicile Splendor de Ettore Scola Cinema Paradiso de Guiseppe Tornatore Gérard Grugeau Denys Arcand Number 44-45, Fall 1989 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/23135ac See table of contents Publisher(s) 24/30 I/S ISSN 0707-9389 (print) 1923-5097 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Grugeau, G. (1989). Review of [Bon baisers de Sicile / Splendor de Ettore Scola / Cinema Paradiso de Guiseppe Tornatore]. 24 images, (44-45), 22–23. Tous droits réservés © 24 images inc., 1989 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ SPLENDOR CINEMA PARADISO DE ETTORE SCOLA DE GUISEPPE TORNATORE Splendor de Ettore Scola BON BAISERS DE SICILE par Gérard Grugeau es chiffres parlent d'eux-mêmes: de nos émotions collectives face à un d'un cinéma italien qui refuse de déclarer rien qu'en Italie, 7000 salles de monde d'images s'ouvrant à l'infini sur de forfait. L cinéma ont baissé le rideau en dix vastes horizons insoupçonnés. Hélas, les héros sont fatigués et à bout ans. Triste état des lieux d'un art qu'on ne Le Splendor dresse sa façade de tem de souffle. -

15X21 DICEMBRE:Layout 1

dicembre gennaio QUINapoli 2010/11 Infopoint Azienda Autonoma di Indice / Contents Soggiorno Cura e Turismo di Napoli: Monumenti . .3 via San Carlo 9 Monuments tel. 081 402394 Eventi del mese . .41 [email protected] Events of the month Piazza del Gesù, 7 Alberghi . .56 tel. 081 5512701 Hotels 081 5523328 Affittacamere . .63 [email protected] Rent Rooms via Santa Lucia, 107 B&B . .64 tel. 081 2457475 Ostelli / Hostels . .67 081 7647064 Ristoranti . .68 fax 081 2452458 Napoli Restaurants QUI Pizzerie . .70 EPT - sede Centrale Pizza restaurants Piazza dei Martiri 58 è una pubblicazione dell’Azienda Autonoma Cucina Etnica . .71 Napoli Soggiorno, Cura e Turismo di Napoli Ethnic Food tel. 081 4107211 Aut. Trib. Napoli n. 3102 del 7/4/1982 UnicoCampania . .73 fax 081 401961 Dicembre 2010 - Gennaio 2011 Treni . .76 Trains Comune di Napoli Direttore Responsabile Osservatorio Turistico Autolinee . .78 Buses Roberta D’Agostino Culturale Piazza del Plebiscito Aliscafi . .79 In redazione Colonnato della Chiesa Hydrofoils Fabiana Calemma, Raffaella Capozzi, di San Francesco di Paola Traghetti / Navi . .80 Maurizio Cerullo, Domenico Guida tel. 081 7956161/62 Ferries / Ships foto di copertina: Enzo Barbieri Collegamenti da e per URP Comune di Napoli l’aereoporto . .83 Transport from/ to airport traduzioni testi: Laura Caliendo Piazza Municipio Palazzo San Giacomo ArteCard . .84 Azienda Autonoma di Soggiorno tel. 081 7955000 CitySightseeing . .85 Cura e Turismo di Napoli www.comune.napoli.it Autonoleggi . .86 Palazzo Reale Car Rental Piazza del Plebiscito 1 per informazioni e 80132 Napoli Mezzi di trasporto aggiornamenti consultare per i Musei . .87 tel. 081 2525711 il sito: www.inaples.it Transport to Museums fax 081 418619 Consolati . -

Lina Sastri — Antonio Sinagra

V EDIZIONE Giovedì 13 agosto ore 21.00 • Thursday august 13 9.00 pm Aperia EDUARDO MIO maestro di vita e di palcoscenico di e con / with and by Lina Sastri — Antonio Sinagra dirige l’Orchestra Filarmonica Giuseppe Verdi di Salerno conducts the Orchestra Filarmonica Giuseppe Verdi di Salerno Lina Sastri Ensemble in “Eduardo mio, chitarra e direzione / maestro di vita e di guitar and musical direction palcoscenico” Maurizio Pica “Spettacolo in parole, mandolino / mandolin musica e poesia Michele de Martino che racconta il «mio contrabasso / double bass Eduardo» attraverso i Luigi Sigillo miei ricordi personali violino / violin della sua conoscenza Gennaro Desiderio in teatro e nella vita. pianoforte / piano Programma L’uomo Eduardo Ciro Cascino attraverso lettere, poesie percussioni / percussion Programme e qualche citazione Gianluca Mirra delle sue opere. Il tutto accompagnato dalla Antonio Sinagra musica. Che lui molto dirige / conducts amava.” l’Orchestra Filarmonica Lina Sastri Giuseppe Verdi di Salerno / the Orchestra Filarmonica Lina Sastri Giuseppe Verdi di Salerno in “Eduardo mio, a mentor in life and on the stage“ “A show in words, music and Ideazione, drammaturgia e regia / poetry that tells the story of Concept, dramaturgy and direction «my Eduardo» through my Lina Sastri personal memories of my acquaintance with him in the Orchestrazioni ed elaborazioni / theatre and life. Eduardo, a portrait of the man himself Orchestration and formulation through letters, poems and Antonio Sinagra - Maurizio Pica a few quotations from his works. -

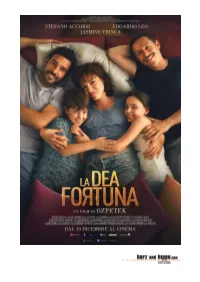

DS 1920-La-Dea-Fortuna.Pdf

L’ulmo lavoro di Ozpetk è un grande ritorno: un film dall'energia vitale insopprimibile che ci fa ridere, commuovere e senre tu parte di un'umanità dolente e spaventata, grazie a una sceneggiatura struggente ed equilibrata e a un cast in stato di grazia. scheda tecnica un film di Ferzan Ozpetek; con Stefano Accorsi Edoardo Leo Jasmine Trinca, Sara Ciocca, Edoardo Brandi, Barbara Alber, Serra Yilmaz, Crisna Bugay, Filippo Nigro; sceneggiatura: Gianni Romoli, Silvia Ranfagni, Ferzan Ozpetek; fotografia: Gian Filippo Corcelli; montaggio: Pietro Morana; musiche: Pasquale Catalano produzione: Warner Bros. Entertainment Italia; distribuzione: Warner Bros. Pictures; Italia, 2019; 118 minu Ferzan Ozpetek Fratello dell'arice Zeynep Zksu, Ferzan Ozpetek arriva in Italia per studiare Storia del Cinema all'Università La Sapienza di Roma nel 1978, entrando nel mondo del cinema in qualità di aiuto regista per importan autori: il suo primo incarico è quello di portare the e un biscoo, tu i pomeriggi alla stessa ora, a Massimo Troisi sul set di Scusate il ritardo (1982). Divenuto poi assistente e aiuto regista per Maurizio Ponzi (Qualcosa di biondo, Il tenente dei Carabinieri), ma anche per Lamberto Bava (Il maestro del terrore, 1988), Ricky Tognazzi (Ultrà e La scorta) e Marco Risi (Il branco, 1994), viene incoraggiato e aiutato a compiere un passo verso la regia da Gianni Amelio ed Elio Petri. È proprio Marco Risi, con la sua casa di produzione (la "Sorpasso Film"), a produrre il suo primo film: Il bagno turco (1997), vero e proprio omaggio alla terra d'origine, con Alessandro Gassman nei panni di un architeo sposato che viene sconvolto dalla scoperta di un mondo completamente nuovo. -

PROGRAMACIÓN Noviembre 2018

PROGRAMACIÓN noviembre 2018 cine universitario Fantasía. Scorsese. Para volver a ver... Cien años de Rita Hayworth. Anime. Cine licencioso. Los socios programan. Rock & Roll. ¡Out! Animación francesa. ASÓCIATE a cine universitario Anuales. EDITORIAL 1 persona .valor de la cuota - $2800 En el mes de octubre, Cine Universitario del .antes del 30/11, descuento 10% - $2500 Uruguay tendrá al terror como protagonista, .antes del receso de diciembre - $2600 enmarcando diferentes épocas, estilos y 2 personas temáticas. .valor de la cuota - $4600 Nuestro ciclo central se enmarcará en la figura .antes del 30/11, descuento 10% - $4100 de Vincent Price (1911-1993), actor de cine .antes del receso de diciembre - $4300 estadounidense de amplia trayectoria en el Cuota mensual. cine de terror, principalmente en películas consideradas “Clase B”. Muchas de estas 1 persona $280 2 personas $460 películas han sido influencia de importantes realizadores de la actualidad, como Tim Burton o David Cronenberg. Siguiendo con el género de terror, en nuestros fines de semana se repasaran algunos clásicos, como por ej. Halloween, Pesadilla en lo profundo de la noche o Viernes 13. cine universitario Se realizará, a su vez, un homenaje a Burt Reynolds, actor, director y productor Consejo Directivo. estadounidense, fallecido en el pasado mes de setiembre, con un conjunto de sus Joaquín Godoy, Nicolas Erramuspe y trabajos llamativos. Destacan en esta lista El Jhonnatan Lemole ( Directores Ejecutivos ). rompehuesos, dirigida por Robert Aldrich y Santiago Lopez ( Tesorero ). Andrea Armani, Juegos de placer, dirigida por Paul Thomas Maite Gomez, Guillermo Cresci y Osvaldo Anderson, entre otras. Rodriguez También, nuestra programación contará ( Consejeros ). -

Ferzan Ozpetek

ALESSANDRO FRANCESCA GASSMAN D’AloJA directed by FERZAN OZPETEK Ferzan Ozpetek Steam – The Turkish Bath by Mario Sesti Ferzan Ozpetek, a summary Born in Istanbul on 3rd February 1959, Ferzan Ozpetek spent his childhood surrounded by women: his mother, a lover of art and music, and his grandmother, a wise and caring presence. Both unquestionably helped foster his artistic development and decision to become a filmmaker. When he was very young the first film he ever saw enchanted him: Mankiewicz’s sumptuous Cleopatra. The kitsch impact of this staging had an explosive and memorable effect on him. The opulence of the costumes, the monumental style of Hollywood kitsch in the reconstruction of ancient times and the melodramatic expressiveness of the couple Liz Taylor and Richard Burton marked his attention. Despite the strong bond with his homeland and family, he decided to move to Rome at the age of 17 where he attended the Academy of Dramatic Arts “Silvio D’Amico”, thus coming into contact with Julian Beck’s Living Theater, one of the most important experimental theaters of that period; he then reverted to his true passion and went to university to study History of Cinema. 2 Ferzan Ozpetek, a summary Thanks to his collaboration with a film magazine, he had the opportunity to interview some of the most important Italian directors and found a job as an assistant director on the set of Scusate il ritardo by Massimo Troisi (1983). This was his first real experience on a movie set. In the following years he worked with Maurizio Ponzi, Ricki Tognazzi, Francesco Nuti, Sergio Citti, and Marco Risi but he already had a story in mind, an idea for his first film as a director. -

ND Announces New Trustees

----~- ---- - --· Monday, February 19, 1996• Vol. XXVII No. 92 THE INDEPENDENT NEWSPAPER SERVING NOTRE DAME AND SAINT MARY'S Tax assistance provides 'real world' experience By MAUREEN HURLEY pared," said Saint Mary's alumna and Saint Mary's New~ Editor CPA Kristi Horvath, who volunteers with the program. "Anytime I've been there, I·:veryone's favorite time of the year is there has been an excellent turnout." approaehing. Student participants agree on the pro Tax time. gram's community impact. "The pro Saint Mary's and Notre Dame stu gram is for the working poor. We can dents, staff members hopefully get them tax advantages and ai1d Miehiana resi tax breaks, without them having to pay dents with an annual consultation fees," said Saint Mary's ineome of less than business major Danielle Fikel. $25,000 for 1995 are Milani stresses the real-world experi nligible for free tax ence accounting majors receive, along eonsultation through with the service provided to the commu the Tax Assistanee nity. "These are real people, and real Program· L--~-'-M-"'i"'-la_n_i...__..___, money," he said. "This isn't just a hypo "It's thn largest pro thetical textbook problem." gram in Indiana," said Claude Henshaw, business professor Ken Milani, coordinator and professor of' and Saint Mary's coordinator, said the aeeountancy at Notre Dame. students receive highly specialized train Aeeounting majors, along with staff ing students to prepare the federal and members from six Michiana accounting state tax returns. "They're trained to firms, ofTnr free consultation at campus help these low-income clients take sitns, along with loeations at local advantage of the tax laws, get deduc libraries and neighborhood centers.