WRAP Theses Jesson 2018.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hervey-Grimes-Resume.Pdf

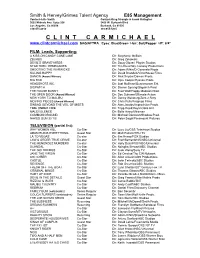

Smith & Hervey/Grimes Talent Agency E85 Management Contact-Julie Smith Contact-Greg Strangis & Jacob Gallagher 3002 Midvale Ave. Suite 206 3406 W. Burbank Blvd Los Angeles, Ca 90034 Burbank, Ca 91505 310-475-2010 310-955-5835 C L I N T C A R M I C H A E L www.clintcarmichael.com SAG/AFTRA Eyes: Blue/Green Hair: Salt/Pepper HT: 6’4” FILM: Leads, Supporting: A KISS ON CANDY CANE LANE Dir: Stephanie McBain ZBURBS Dir: Greg Zekowski DEVIL’S GRAVEYARDS Dir: Doug Glover/ Pilgrim Studios STAR TREK: RENEGADES Dir: Tim Russ/Sky Conway Productions SHOOTING THE WARWICKS Dir: Adam Rifkin/D-Generate Prods KILLING HAPPY Dir: David Brandvik/Victorhouse Films DAMON (Award Winner) Dir: Nick Snyder/Damon Prods. BIG BAD Dir: Opie Cooper/Eyevox Prods. HEADSHOTS INC. Dir: Joel Hoffman/Quarterwater Ent. DISPATCH Dir: Steven Sprung/Dispatch Prod. THE HOUSE BUNNY Dir: Fred Wolf/Happy Madison Prod. THE OPEN DOOR (Award Winner) Dir: Doc Duhame/Ultimate Action NEW YORK TO MALIBU Dir: Danny Weisberg/Zero 2 Sixty MOVING PIECES (Award Winner) Dir: Chris Pulis/Froglegs Films SINBAD: BEYOND THE VEIL OF MISTS Dir: Alan Jacobs/Improvision Prods. TIME UNDER FIRE Dir: Tripp Reed/Royal Oaks Ent. MALEVOLENCE Dir: Belle Avery/Miramax COMMON GROUND Dir: Michael Donovan/Shadow Prod. NAKED GUN 33 1/3 Dir: Peter Segal/Paramount Pictures TELEVISION (partial list): WHY WOMEN KILL Co-Star Dir: Lucy Liu/CBS Television Studios ADAM RUINS EVERYTHING Guest Star Dir: Matt Pollack/TRU TV LA TO VEGAS Co-star Dir: Jim Hensz/FOX Studios LAW & ORDER TRUE CRIME Co-star Dir: Fred -

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

Extreme Art Film: Text, Paratext and DVD Culture Simon Hobbs

Extreme Art Film: Text, Paratext and DVD Culture Simon Hobbs The thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Portsmouth. September 2014 Declaration Whilst registered as a candidate for the above degree, I have not been registered for any other research award. The results and conclusions embodied in this thesis are the work of the named candidate and have not been submitted for any other academic award. Word count: 85,810 Abstract Extreme art cinema, has, in recent film scholarship, become an important area of study. Many of the existing practices are motivated by a Franco-centric lens, which ultimately defines transgressive art cinema as a new phenomenon. The thesis argues that a study of extreme art cinema needs to consider filmic production both within and beyond France. It also argues that it requires an historical analysis, and I contest the notion that extreme art cinema is a recent mode of Film production. The study considers extreme art cinema as inhabiting a space between ‘high’ and ‘low’ art forms, noting the slippage between the two often polarised industries. The study has a focus on the paratext, with an analysis of DVD extras including ‘making ofs’ and documentary featurettes, interviews with directors, and cover sleeves. This will be used to examine audience engagement with the artefacts, and the films’ position within the film market. Through a detailed assessment of the visual symbols used throughout the films’ narrative images, the thesis observes the manner in which they engage with the taste structures and pictorial templates of art and exploitation cinema. -

Realist Cinema As World Cinema Non-Cinema, Intermedial Passages, Total Cinema Lúcia Nagib Realist Cinema As World Cinema

FILM CULTURE IN TRANSITION Realist Cinema as World Cinema Non-cinema, Intermedial Passages, Total Cinema lúcia nagib Realist Cinema as World Cinema Realist Cinema as World Cinema Non-cinema, Intermedial Passages, Total Cinema Lúcia Nagib Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Photo by Mateo Contreras Gallego, for the film Birds of Passages (Pájaros de Verano, Cristina Gallego and Ciro Guerra, 2018), courtesy of the authors. Cover design: Kok Korpershoek Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6298 751 7 e-isbn 978 90 4853 921 5 doi 10.5117/9789462987517 nur 670 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) L. Nagib / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2020 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). Every effort has been made to obtain permission to use all copyrighted illustrations reproduced in this book. Nonetheless, whosoever believes to have rights to this material is advised to contact the publisher. Table of Contents List of Illustrations 7 Acknowledgements 11 Introduction 15 Part I Non-cinema 1 The Death of (a) Cinema 41 The State of Things 2 Jafar Panahi’s Forbidden Tetralogy 63 This Is Not a Film, Closed Curtain, Taxi Tehran, Three Faces 3 Film as Death 87 The Act of Killing 4 The Blind Spot of History 107 Colonialism in Tabu Part II -

J^Slirn Scenes Are Completely Unre- 40

am ________ status Perelman said: “Frankly,l ! major in playwright-! THE EVENING STAR problems ernet Maugham about cutting.! 120 ot hFr prettleat bonnet* a* Monday, If beautiful young girls to! A-16 Washington, 0. C, April 27, 1957 were mg, because authors are Maugham said: "My model* and (Ift* to mil- go my 1 reluct- rule is—if Soviet Into Cartier's and use ant to alter a word of their you . Paul Ford will freely—it have to think about it, cut liner* re- name would be ut- masterpieces. One veteran al- it.- place David Burn* a* the May- *¦> terly meaningless.” ways ** * * I . j consoled himself: “That or in “The Music Man” . THE PASSING SHOW * * k ** which is cut can't be hissed Sally Victor is leaving for When Sol Hurok, the impre- Ernie Kovars, who never tried at." Garson Kanin asked Som- Russia ' next month. She's taking See LYONS DEN, Pace A-11 bringing a coal to Newcastle, I 1 Gabin at Marseille did bring 800 Havana cigars to m Cuba. Kovacs. who went there for a role in "Our Man in Ha- vana.” convinced the Customs A Waste of, Talent officials that he invariably car- By HARRY MarARTHUR ries this hoard with him goes •Ur aud Writer wherever he .... Gene The waste of talent Is not a caprice of the Hollywood movie Fowler's memoirs of the '2os mills alone. It can happen elsewhere, too. It happens In fact, will be titled "Skyline” .... to no leas an actor than France's Jean Gabin in “The House on Among the 100 speaking roles in "John Paul Jones” two of the Waterfront.” the week end's new arrival at the Plaza are Films More Than Routine Merit DRIVE-IN Theater. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 391 195 CS 509 138 AUTHOR Tillman, Lisa M.; Bochner, Arthur P. TITLE Seeing Through Film: Cinemaas Inquiry An

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 391 195 CS 509 138 AUTHOR Tillman, Lisa M.; Bochner, Arthur P. TITLE Seeing through Film: Cinemaas Inquiry and Pedagogy. PUB DATE Nov 95 NOTE 12p.; Paper presented at the AnnualMeeting of the Speech Communication Association (8Ist, SanAntonio, TX, November 18-21, 1995). PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) Speeches/Conference Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MFOI/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Audience Response; Communication (ThoughtTransfer); *Critical Thinking; *Film Criticism; *FilmStudy; Higher Education; InstructionalEffectiveness; *Relationship; Undergraduate Students IDENTIFIERS *Film Viewing; University of SouthFlorida ABSTRACT An undergraduate course at the Universityof South Florida called "Relationshipson Film" treats movies as relationship texts to be "read" by active viewers. Throughthe semester, students engage film in two ways. First, they interpret filmsas response papers. Each week, students watch the assigned filmoutside of class. Then they select the relational issuesthey want to address, and write about what they find most evocative,interesting, or questionable. Second, students turna reflexive eye onto themselves and ask what values arid assumptionsthey use to interpret relationship experience. In other words,after students write about issues they select, they examine theiranalyses and consider such questions as, "How am I positionedas a viewer of this film?" or "What does my selection of theseissues say about me?" These questions call students to examine criticallytheir own structures of interpretation--their memories, their familytraditions, their cultural Cairo," two films that affirmthat people today live in what N. Denzin Cairo," 2 films that affirmthat people today live in what N. Denzin calls "a cinematic society."These "movies about movies" suggest that film mediates identity andrelationships in several ways. -

Download the List of History Films and Videos (PDF)

Video List in Alphabetical Order Department of History # Title of Video Description Producer/Dir Year 532 1984 Who controls the past controls the future Istanb ul Int. 1984 Film 540 12 Years a Slave In 1841, Northup an accomplished, free citizen of New Dolby 2013 York, is kidnapped and sold into slavery. Stripped of his identity and deprived of dignity, Northup is ultimately purchased by ruthless plantation owner Edwin Epps and must find the strength to survive. Approx. 134 mins., color. 460 4 Months, 3 Weeks and Two college roommates have 24 hours to make the IFC Films 2 Days 235 500 Nations Story of America’s original inhabitants; filmed at actual TIG 2004 locations from jungles of Central American to the Productions Canadian Artic. Color; 372 mins. 166 Abraham Lincoln (2 This intimate portrait of Lincoln, using authentic stills of Simitar 1994 tapes) the time, will help in understanding the complexities of our Entertainment 16th President of the United States. (94 min.) 402 Abe Lincoln in Illinois “Handsome, dignified, human and moving. WB 2009 (DVD) 430 Afghan Star This timely and moving film follows the dramatic stories Zeitgest video 2009 of your young finalists—two men and two very brave women—as they hazard everything to become the nation’s favorite performer. By observing the Afghani people’s relationship to their pop culture. Afghan Star is the perfect window into a country’s tenuous, ongoing struggle for modernity. What Americans consider frivolous entertainment is downright revolutionary in this embattled part of the world. Approx. 88 min. Color with English subtitles 369 Africa 4 DVDs This epic series presents Africa through the eyes of its National 2001 Episode 1 Episode people, conveying the diversity and beauty of the land and Geographic 5 the compelling personal stories of the people who shape Episode 2 Episode its future. -

Introduction

NOTES INTRODUCTION 1. Nathanael West, The Day of the Locust (New York: Bantam, 1959), 131. 2. West, Locust, 130. 3. For recent scholarship on fandom, see Henry Jenkins, Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture (New York: Routledge, 1992); John Fiske, Understanding Popular Culture (New York: Routledge, 1995); Jackie Stacey, Star Gazing (New York: Routledge, 1994); Janice Radway, Reading the Romance (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1991); Joshua Gam- son, Claims to Fame: Celebrity in Contemporary America (Berkeley: Univer- sity of California Press, 1994); Georganne Scheiner, “The Deanna Durbin Devotees,” in Generations of Youth, ed. Joe Austin and Michael Nevin Willard (New York: New York University Press, 1998); Lisa Lewis, ed. The Adoring Audience: Fan Culture and Popular Media (New York: Routledge, 1993); Cheryl Harris and Alison Alexander, eds., Theorizing Fandom: Fans, Subculture, Identity (Creekskill, N.J.: Hampton Press, 1998). 4. According to historian Daniel Boorstin, we demand the mass media’s simulated realities because they fulfill our insatiable desire for glamour and excitement. To cultural commentator Richard Schickel, they create an “illusion of intimacy,” a sense of security and connection in a society of strangers. Ian Mitroff and Warren Bennis have gone as far as to claim that Americans are living in a self-induced state of unreality. “We are now so close to creating electronic images of any existing or imaginary person, place, or thing . so that a viewer cannot tell whether ...theimagesare real or not,” they wrote in 1989. At the root of this passion for images, they claim, is a desire for stability and control: “If men cannot control the realities with which they are faced, then they will invent unrealities over which they can maintain control.” In other words, according to these authors, we seek and create aural and visual illusions—television, movies, recorded music, computers—because they compensate for the inadequacies of contemporary society. -

University of Huddersfield Repository

University of Huddersfield Repository Billam, Alistair It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Original Citation Billam, Alistair (2018) It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema. Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/34583/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Submission in fulfilment of Masters by Research University of Huddersfield 2016 It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Alistair Billam Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1: Ealing and post-war British cinema. ................................................................................... 12 Chapter 2: The community and social realism in It Always Rains on Sunday ...................................... 25 Chapter 3: Robert Hamer and It Always Rains on Sunday – the wider context. -

Modus Operandi Films and High Point Media Group Present

Modus Operandi Films and High Point Media Group Present A film by Craig McCall Worldwide Sales: High Point Media Group Contact in Cannes: Residences du Grand Hotel, Cormoran II, 3 rd Floor: Tel: +33 (0) 4 93 38 05 87 London Contact: Tel: +44 20 7424 6870. Fax +44 20 7435 3281 [email protected] CAMERAMAN: The Life & Work of Jack Cardiff page 1 of 27 © Modus Operandi Films 2010 HP PRESS KIT CAMERAMAN: The Life and Work of Jack Cardiff www.jackcardiff.com Contents: - Film Synopsis p 3 - 10 Facts About Jack p 4 - Jack Cardiff Filmography p 5 - Quotes about Jack p 6 - Director’s Notes p 7 - Interviewee’s p 8 - Bio’s of Key Crew p10 - Director's Q&A p14 - Credits p 19 CAMERAMAN: The Life & Work of Jack Cardiff page 2 of 27 © Modus Operandi Films 2010 HP PRESS KIT CAMERAMAN : The Life and Work of Jack Cardiff A Documentary Feature Film Logline: Celebrating the remarkable nine decade career of legendary cinematographer, Jack Cardiff, who provided the canvas for classics like The Red Shoes and The African Queen . Short Synopsis: Jack Cardiff’s career spanned an incredible nine of moving picture’s first ten decades and his work behind the camera altered the look of films forever through his use of Technicolor photography. Craig McCall’s passionate film about the legendary cinematographer reveals a unique figure in British and international cinema. Long Synopsis: Cameraman illuminates a unique figure in British and international cinema, Jack Cardiff, a man whose life and career are inextricably interwoven with the history of cinema spanning nine decades of moving pictures' ten. -

EARL CAMERON Sapphire

EARL CAMERON Sapphire Reuniting Cameron with director Basil Dearden after Pool of London, and hastened into production following the Notting Hill riots of summer 1958, Sapphire continued Dearden and producer Michael Relph’s valuable run of ‘social problem’ pictures, this time using a murder-mystery plot as a vehicle to sharply probe contemporary attitudes to race. Cameron’s role here is relatively small, but, playing the brother of the biracial murder victim of the title, the actor makes his mark in a couple of memorable scenes. Like Dearden’s later Victim (1961), Sapphire was scripted by the undervalued Janet Green. Alex Ramon, bfi.org.uk Sapphire is a graphic portrayal of ethnic tensions in 1950s London, much more widespread and malign than was represented in Dearden’s Pool of London (1951), eight years earlier. The film presents a multifaceted and frequently surprising portrait that involves not just ‘the usual suspects’, but is able to reveal underlying insecurities and fears of ordinary people. Sapphire is also notable for showing a successful, middle-class black community – unusual even in today’s British films. Dearden deftly manipulates tension with the drip-drip of revelations about the murdered girl’s life. Sapphire is at first assumed to be white, so the appearance of her black brother Dr Robbins (Earl Cameron) is genuinely astonishing, provoking involuntary reactions from those he meets, and ultimately exposing the real killer. Small incidents of civility and kindness, such as that by a small child on a scooter to Dr Robbins, add light to a very dark film. Earl Cameron reprises a role for which he was famous, of the decent and dignified black man, well aware of the burden of his colour. -

Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND Index 2016_4.indd 1 14/12/2016 17:41 SUBJECT INDEX SUBJECT INDEX After the Storm (2016) 7:25 (magazine) 9:102 7:43; 10:47; 11:41 Orlando 6:112 effect on technological Film review titles are also Agace, Mel 1:15 American Film Institute (AFI) 3:53 Apologies 2:54 Ran 4:7; 6:94-5; 9:111 changes 8:38-43 included and are indicated by age and cinema American Friend, The 8:12 Appropriate Behaviour 1:55 Jacques Rivette 3:38, 39; 4:5, failure to cater for and represent (r) after the reference; growth in older viewers and American Gangster 11:31, 32 Aquarius (2016) 6:7; 7:18, Céline and Julie Go Boating diversity of in 2015 1:55 (b) after reference indicates their preferences 1:16 American Gigolo 4:104 20, 23; 10:13 1:103; 4:8, 56, 57; 5:52, missing older viewers, growth of and A a book review Agostini, Philippe 11:49 American Graffiti 7:53; 11:39 Arabian Nights triptych (2015) films of 1970s 3:94-5, Paris their preferences 1:16 Aguilar, Claire 2:16; 7:7 American Honey 6:7; 7:5, 18; 1:46, 49, 53, 54, 57; 3:5: nous appartient 4:56-7 viewing films in isolation, A Aguirre, Wrath of God 3:9 10:13, 23; 11:66(r) 5:70(r), 71(r); 6:58(r) Eric Rohmer 3:38, 39, 40, pleasure of 4:12; 6:111 Aaaaaaaah! 1:49, 53, 111 Agutter, Jenny 3:7 background