BBC Three Documentary - Don’T Call Me Crazy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

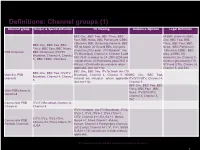

PSB Report Definitions

Definitions: Channel groups (1) Channel group Output & Spend definition TV Viewing Audience Opinion Legal Definition BBC One, BBC Two, BBC Three, BBC All BBC channels (BBC Four, BBC News, BBC Parliament, CBBC, One, BBC Two, BBC CBeebies, BBC streaming channels, BBC Three, BBC Four, BBC BBC One, BBC Two, BBC HD (to March 2013) and BBC Olympics News , BBC Parliament Three, BBC Four, BBC News, channels (2012 only). ITV Network* (inc ,CBeebies, CBBC, BBC PSB Channels BBC Parliament, ITV/ITV ITV Breakfast), Channel 4, Channel 5 and Alba, all BBC HD Breakfast, Channel 4, Channel S4C (S4C is added to C4 2008-2009 and channels), the Channel 3 5,, BBC CBBC, CBeebies excluded from 2010 onwards post-DSO in services (provided by ITV, Wales). HD variants are included where STV and UTV), Channel 4, applicable (but not +1s). Channel 5, and S4C. BBC One, BBC Two, ITV Network (inc ITV BBC One, BBC Two, ITV/ITV Main five PSB Breakfast), Channel 4, Channel 5. HD BBC One, BBC Two, Breakfast, Channel 4, Channel channels variants are included where applicable ITV/STV/UTV, Channel 4, 5 (but not +1s). Channel 5 BBC One, BBC Two, BBC Three, BBC Four , BBC Main PSB channels News, ITV/STV/UTV, combined Channel 4, Channel 5, S4C Commercial PSB ITV/ITV Breakfast, Channel 4, Channels Channel 5 ITV+1 Network (inc ITV Breakfast) , ITV2, ITV2+1, ITV3, ITV3+1, ITV4, ITV4+1, CITV, Channel 4+1, E4, E4 +1, More4, CITV, ITV2, ITV3, ITV4, Commercial PSB More4 +1, Film4, Film4+1, 4Music, 4Seven, E4, Film4, More4, 5*, Portfolio Channels 4seven, Channel 4 Paralympics channels 5USA (2012 only), Channel 5+1, 5*, 5*+1, 5USA, 5USA+1. -

Media Nations 2019

Media nations: UK 2019 Published 7 August 2019 Overview This is Ofcom’s second annual Media Nations report. It reviews key trends in the television and online video sectors as well as the radio and other audio sectors. Accompanying this narrative report is an interactive report which includes an extensive range of data. There are also separate reports for Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The Media Nations report is a reference publication for industry, policy makers, academics and consumers. This year’s publication is particularly important as it provides evidence to inform discussions around the future of public service broadcasting, supporting the nationwide forum which Ofcom launched in July 2019: Small Screen: Big Debate. We publish this report to support our regulatory goal to research markets and to remain at the forefront of technological understanding. It addresses the requirement to undertake and make public our consumer research (as set out in Sections 14 and 15 of the Communications Act 2003). It also meets the requirements on Ofcom under Section 358 of the Communications Act 2003 to publish an annual factual and statistical report on the TV and radio sector. This year we have structured the findings into four chapters. • The total video chapter looks at trends across all types of video including traditional broadcast TV, video-on-demand services and online video. • In the second chapter, we take a deeper look at public service broadcasting and some wider aspects of broadcast TV. • The third chapter is about online video. This is where we examine in greater depth subscription video on demand and YouTube. -

What Is Bbc Three?

We tested the public value of the proposed changes using a combination of quantitative and qualitative methodologies Quantitative methodology Qualitative methodology We ran a 15 minute online survey with 3,281 respondents to We conducted 20 x 2 hour ‘Extended Group’ sessions via Zoom with understand current associations with BBC Three, the appeal of BBC a mix of different audiences to explore and compare reactions, Three launching as a linear channel, and how this might impact from a personal and societal value perspective, to the concept of existing services in the market. BBC Three becoming a linear channel again. In the survey, we explored the following: In the sessions, we explored the following: - Demographics and brand favourability - Linear TV consumption and BBC attitudes - Current TV and video consumption - (S)VOD consumption behaviours, with a focus on BBC Three - BBC Three awareness, usage and perceptions (current) - A BBC Three content evaluation (via BBC Three on iPlayer exploration) - Likelihood of watching new TV channel and perceptions - Responses to the proposal of BBC Three becoming a TV channel - Impact on services currently used (including time taken away from each) - Expected personal and societal impact of the proposed changes - Societal impact of BBC Three launching as a TV channel - Evaluation of proposed changes against BBC Public Purposes 4 The qualitative stage involved 20 x 2-hour extended digital group discussions across the UK with a carefully designed sample 20 x 2 hour Extended Zoom Groups The qualitative -

BBC Learning – Commissioning Meeting

BBC Learning – Commissioning Meeting May 2012 Welcome and Introduction Saul Nassé – Controller, BBC Learning BBC North • BBC Learning is now located at MediaCityUK, Salford • The move to Salford aims to ensure we better serve and reflect Northern audiences • Other departments based here include: o Sport o Children’s o 5 live o Future Media o BBC Breakfast Welcome and Introduction • Our fourth session to share plans and future thinking • This is the second of two sessions held today: o AM – aimed at education publishers and distributors o PM – commissioning meeting for BBC suppliers • Minutes and recordings of both events will be put online Welcome and Introduction At the last meeting in October 2011 we covered: o Update on Learning activity and content o Information on BBC Learning online activity and plans o Emerging thoughts on the Knowledge and Learning Product o Information on BBC Learning television and Learning Zone plans o Update on finance and public affairs activity Agenda model Timing Agenda Item Speaker 2.30pm Introduction and Welcome Saul Nassé – Controller, BBC Learning Learning and Strategy Update The Knowledge and Learning Product Saul Nassé – Controller, BBC Learning Chris Sizemore – Executive Editor, BBC Learning BBC Learning Online Commissioning Chris Sizemore – Executive Editor, BBC Learning BBC Learning Television Abigail Appleton – Head of Commissioning, BBC Learning BBC Two: The Learning Zone Katy Jones – Executive Producer, BBC Learning Finance and Industry Engagement Alex Lloyd – Head of Operations and Public Affairs, -

Annual Report on the BBC 2019/20

Ofcom’s Annual Report on the BBC 2019/20 Published 25 November 2020 Raising awarenessWelsh translation available: Adroddiad Blynyddol Ofcom ar y BBC of online harms Contents Overview .................................................................................................................................... 2 The ongoing impact of Covid-19 ............................................................................................... 6 Looking ahead .......................................................................................................................... 11 Performance assessment ......................................................................................................... 16 Public Purpose 1: News and current affairs ........................................................................ 24 Public Purpose 2: Supporting learning for people of all ages ............................................ 37 Public Purpose 3: Creative, high quality and distinctive output and services .................... 47 Public Purpose 4: Reflecting, representing and serving the UK’s diverse communities .... 60 The BBC’s impact on competition ............................................................................................ 83 The BBC’s content standards ................................................................................................... 89 Overview of our duties ............................................................................................................ 96 1 Overview This is our third -

Ofcom Fact Sheet on Coverage No. 3 2 Why Will Some People Receive More Digital TV Channels Than Others?

1 Ofcom fact sheet on coverage No. 3 2 Why will some people receive more digital TV channels than others? Summary 1.1 Almost everyone will be able to receive the UK’s public service television channels on DTT after switchover. This PSB service currently offers roughly 17 channels, including channels from the BBC, ITV and Channel 4. Other, purely commercial channels, will be less widely available. Coverage and services on digital television 1.2 Digital switchover is the process of converting the UK’s television services from analogue to fully digital. Switchover will take place on a region by region basis starting in 2008 and ending in 2012. To continue receiving television after switchover, consumers who have not already done so will need to upgrade their existing TV equipment to receive digital signals. 1.3 There are a number of different ways to receive digital television, one of which is via an aerial. This is known as Digital Terrestrial Television or DTT and services are provided by a consortium of broadcasters known as Freeview. Other ways to receive digital television include: satellite (either paid for or free), cable, broadband, as well as additional pay services on DTT. Each of these provides consumers with different packages of channels. The number of channels received will therefore vary greatly depending on the option chosen. 1.4 For viewers opting to receive services through their aerial, DTT is made up of six bundles of channels known as multiplexes. Three of these are public service multiplexes and three are commercial multiplexes. 1.5 When digital switchover takes place, the three public service multiplexes will be as widely available as analogue television is now. -

Researching Digital on Screen Graphics Executive Sum M Ary

Researching Digital On Screen Graphics Executive Sum m ary Background In Spring 2010, the BBC commissioned independent market research company, Ipsos MediaCT to conduct research into what the general public, across the UK thought of Digital On Screen Graphics (DOGs) – the channel logos that are often in the corner of the TV screen. The research was conducted between 5th and 11th March, with a representative sample of 1,031 adults aged 15+. The research was conducted by interviewers in-home, using the Ipsos MORI Omnibus. The key findings from the research can be found below. Key Findings Do viewers notice DOGs? As one of our first questions we split our sample into random halves and showed both halves a typical image that they would see on TV. One was a very busy image, with a DOG present in the top left corner, the other image had much less going on, again with the DOG in the top left corner. We asked respondents what the first thing they noticed was, and then we asked what they second thing they noticed was. It was clear from the results that the DOGs did not tend to stand out on screen, with only 12% of those presented with the ‘less busy’ screen picking out the DOG (and even fewer, 7%, amongst those who saw the busy screen). Even when we had pointed out DOGs and talked to respondents specifically about them, 59% agreed that they ‘tend not to notice the logos’, with females and viewers over 55, the least likely to notice them according to our survey. -

PSB Output and Spend

B - PSB Output and Spend PSB Report 2012 – Information pack Contents Page • Background 2 • PSB spend 4 • PSB first run originations 14 • UK/national News and Current Affairs 19 • UK/national News 21 • Current Affairs 23 • Non-network output in the nations and English regions 25 • Factual 29 • Factual output by sub-genre 30 • Specialist Factual – peak time first run originated output 31 • Arts, Education and Religion/Ethics 32 • Children’s PSB output and expenditure 35 • Drama, Soap, Sport and Comedy output 38 1 Background (1) • This information pack contains data gathered through Ofcom’s Market Intelligence database in order to provide a picture of the PSB programming and spend over the last five years on PSB channels. • The data in this report are collected by Ofcom from the broadcasters each year, as part of their PSB returns and include figures on the volume of hours broadcast during the year and programme expenditure. Notes on the data • PSB Channels – Where possible data has been provided for BBC One, BBC Two, ITV1, ITV Breakfast, Channel 4, Channel 5 and the BBC’s PSB digital channels: BBC Three, BBC Four, CBBC, Cbeebies, BBC News and BBC Parliament. BBC HD has been excluded from much of the analysis in the report as much of its output is simulcast from the core BBC channels and therefore would represent a disproportionate amount of broadcast hours and spend. Please refer to individual footnotes and chart details indicating when a smaller group of these channels is reported on. ITV1 includes GMTV1 unless otherwise stated. Data for S4C is shown in a separate section, apart from S4C’s children’s output which is included within the children’s section of the report. -

BRITISH ACADEMY TELEVISION CRAFT AWARDS in 2016: Winners in *BOLD

BRITISH ACADEMY TELEVISION CRAFT AWARDS IN 2016: Winners in *BOLD SPECIAL AWARD *NINA GOLD BREAKTHROUGH TALENT sponsored by Sara Putt Associates DC MOORE (Writer) Not Safe for Work- Clerkenwell Films/Channel 4 GUILLEM MORALES (Director) Inside No. 9 - The 12 Days of Christine - BBC Productions/BBC Two MARCUS PLOWRIGHT (Director) Muslim Drag Queens - Swan films/Channel 4 *MICHAELA COEL (Writer) Chewing Gum - Retort/E4 COSTUME DESIGN sponsored by Mad Dog Casting BARBARA KIDD Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell - Cuba Pictures/Feel Films/BBC One *FOTINI DIMOU The Dresser - Playground Television UK Limited, Sonia Friedman Productions, Altus Productions, Prescience/BBC Two JOANNA EATWELL Wolf Hall - Playground Entertainment, Company Pictures/BBC Two MARIANNE AGERTOFT Poldark - Mammoth Screen Limited/BBC One DIGITAL CREATIVITY ATHENA WITTER, BARRY HAYTER, TERESA PEGRUM, LIAM DALLEY I'm A Celebrity... Get Me Out of Here! - ITV Consumer Ltd *DEVELOPMENT TEAM Humans - Persona Synthetics - Channel 4, 4creative, OMD, Microsoft, Fuse, Rocket, Supernatural GABRIEL BISSET-SMITH, RACHEL DE-LAHAY, KENNY EMSON, ED SELLEK The Last Hours of Laura K - BBC MIKE SMITH, FELIX RENICKS, KIERON BRYAN, HARRY HORTON Two Billion Miles - ITN DIRECTOR: FACTUAL ADAM JESSEL Professor Green: Suicide and Me - Antidote Productions/Globe Productions/BBC Three *DAVE NATH The Murder Detectives - Films of Record/Channel 4 JAMES NEWTON The Detectives - Minnow Films/BBC Two URSULA MACFARLANE Charlie Hebdo: Three Days That Shook Paris - Films of Record/More4 DIRECTOR: FICTION sponsored -

Culture, Media and Sport Committee

House of Commons Culture, Media and Sport Committee Future of the BBC Fourth Report of Session 2014–15 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 10 February 2015 HC 315 INCORPORATING HC 949, SESSION 2013-14 Published on 26 February 2015 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Culture, Media and Sport Committee The Culture, Media and Sport Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration and policy of the Department for Culture, Media and Sport and its associated public bodies. Current membership Mr John Whittingdale MP (Conservative, Maldon) (Chair) Mr Ben Bradshaw MP (Labour, Exeter) Angie Bray MP (Conservative, Ealing Central and Acton) Conor Burns MP (Conservative, Bournemouth West) Tracey Crouch MP (Conservative, Chatham and Aylesford) Philip Davies MP (Conservative, Shipley) Paul Farrelly MP (Labour, Newcastle-under-Lyme) Mr John Leech MP (Liberal Democrat, Manchester, Withington) Steve Rotheram MP (Labour, Liverpool, Walton) Jim Sheridan MP (Labour, Paisley and Renfrewshire North) Mr Gerry Sutcliffe MP (Labour, Bradford South) The following Members were also a member of the Committee during the Parliament: David Cairns MP (Labour, Inverclyde) Dr Thérèse Coffey MP (Conservative, Suffolk Coastal) Damian Collins MP (Conservative, Folkestone and Hythe) Alan Keen MP (Labour Co-operative, Feltham and Heston) Louise Mensch MP (Conservative, Corby) Mr Adrian Sanders MP (Liberal Democrat, Torbay) Mr Tom Watson MP (Labour, West Bromwich East) Powers The Committee is one of the Departmental Select Committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. -

Final Determination Annex 2: Channel Take-Up and Substitution

BBC Scotland Competition Assessment Final Determination Annex 2: Channel Take-up and Substitution STATEMENT ANNEX Publication Date: 26 June 2018 BBC Scotland Competition Assessment – Final Determination Annex 2: Channel Take-up and Substitution A2. Channel Take-up and Substitution Introduction A2.1 In order to review the public value and assess the potential impact on fair and effective competition of the BBC’s proposal, we must first consider the audience that the new BBC Scotland channel is likely to attract. This Annex provides our assessment of the likely ’take- up’ of the BBC Scotland channel, i.e. the viewing hours the new channel is likely to attract in Scotland and the viewing share and audience reach it is likely to achieve.1 A2.2 The BBC’s proposal involves associated changes to existing BBC services, in particular BBC Two, BBC Four and CBBC HD in Scotland. We therefore also assess the effect on the viewing of BBC Two, BBC Four and CBBC in Scotland resulting from the BBC’s proposal. A2.3 We then identify the services most likely to be affected by the proposed new channel and the associated changes. We assess the potential audience substitution, including from existing BBC services and commercial services. A2.4 This Annex broadly reflects the assessment of take-up and substitution set out in our Consultation. Where relevant, we have set out the stakeholder views we received in response to our Consultation and how these, along with any further analysis, have influenced our assessment of take-up and substitution. In particular, we set out and respond to stakeholders’ views on: our take-up estimates for the new channel (paragraphs A2.104 to A2.135); and substitution from existing TV channels as a result of the BBC proposal (paragraphs A2.162 to A2.171). -

MGEITF Prog Cover V2

Contents Welcome 02 Sponsors 04 Festival Information 09 Festival Extras 10 Free Clinics 11 Social Events 12 Channel of the Year Awards 13 Orientation Guide 14 Festival Venues 15 Friday Sessions 16 Schedule at a Glance 24 Saturday Sessions 26 Sunday Sessions 36 Fast Track and The Network 42 Executive Committee 44 Advisory Committee 45 Festival Team 46 Welcome to Edinburgh 2009 Tim Hincks is Executive Chair of the MediaGuardian Elaine Bedell is Advisory Chair of the 2009 Our opening session will be a celebration – Edinburgh International Television Festival and MediaGuardian Edinburgh International Television or perhaps, more simply, a hoot. Ant & Dec will Chief Executive of Endemol UK. He heads the Festival and Director of Entertainment and host a special edition of TV’s Got Talent, as those Festival’s Executive Committee that meets five Comedy at ITV. She, along with the Advisory who work mostly behind the scenes in television times a year and is responsible for appointing the Committee, is directly responsible for this year’s demonstrate whether they actually have got Advisory Chair of each Festival and for overall line-up of more than 50 sessions. any talent. governance of the event. When I was asked to take on the Advisory Chair One of the most contentious debates is likely Three ingredients make up a great Edinburgh role last year, the world looked a different place – to follow on Friday, about pay in television. Senior TV Festival: a stellar MacTaggart Lecture, high the sun was shining, the banks were intact, and no executives will defend their pay packages and ‘James Murdoch’s profile and influential speakers, and thought- one had really heard of Robert Peston.