When a TV Channel Reinvents Itself Online: Post-Broadcast Consumption and Content Change at BBC Three

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

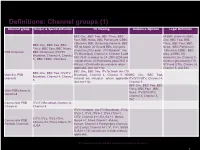

PSB Report Definitions

Definitions: Channel groups (1) Channel group Output & Spend definition TV Viewing Audience Opinion Legal Definition BBC One, BBC Two, BBC Three, BBC All BBC channels (BBC Four, BBC News, BBC Parliament, CBBC, One, BBC Two, BBC CBeebies, BBC streaming channels, BBC Three, BBC Four, BBC BBC One, BBC Two, BBC HD (to March 2013) and BBC Olympics News , BBC Parliament Three, BBC Four, BBC News, channels (2012 only). ITV Network* (inc ,CBeebies, CBBC, BBC PSB Channels BBC Parliament, ITV/ITV ITV Breakfast), Channel 4, Channel 5 and Alba, all BBC HD Breakfast, Channel 4, Channel S4C (S4C is added to C4 2008-2009 and channels), the Channel 3 5,, BBC CBBC, CBeebies excluded from 2010 onwards post-DSO in services (provided by ITV, Wales). HD variants are included where STV and UTV), Channel 4, applicable (but not +1s). Channel 5, and S4C. BBC One, BBC Two, ITV Network (inc ITV BBC One, BBC Two, ITV/ITV Main five PSB Breakfast), Channel 4, Channel 5. HD BBC One, BBC Two, Breakfast, Channel 4, Channel channels variants are included where applicable ITV/STV/UTV, Channel 4, 5 (but not +1s). Channel 5 BBC One, BBC Two, BBC Three, BBC Four , BBC Main PSB channels News, ITV/STV/UTV, combined Channel 4, Channel 5, S4C Commercial PSB ITV/ITV Breakfast, Channel 4, Channels Channel 5 ITV+1 Network (inc ITV Breakfast) , ITV2, ITV2+1, ITV3, ITV3+1, ITV4, ITV4+1, CITV, Channel 4+1, E4, E4 +1, More4, CITV, ITV2, ITV3, ITV4, Commercial PSB More4 +1, Film4, Film4+1, 4Music, 4Seven, E4, Film4, More4, 5*, Portfolio Channels 4seven, Channel 4 Paralympics channels 5USA (2012 only), Channel 5+1, 5*, 5*+1, 5USA, 5USA+1. -

Media Nations 2019

Media nations: UK 2019 Published 7 August 2019 Overview This is Ofcom’s second annual Media Nations report. It reviews key trends in the television and online video sectors as well as the radio and other audio sectors. Accompanying this narrative report is an interactive report which includes an extensive range of data. There are also separate reports for Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The Media Nations report is a reference publication for industry, policy makers, academics and consumers. This year’s publication is particularly important as it provides evidence to inform discussions around the future of public service broadcasting, supporting the nationwide forum which Ofcom launched in July 2019: Small Screen: Big Debate. We publish this report to support our regulatory goal to research markets and to remain at the forefront of technological understanding. It addresses the requirement to undertake and make public our consumer research (as set out in Sections 14 and 15 of the Communications Act 2003). It also meets the requirements on Ofcom under Section 358 of the Communications Act 2003 to publish an annual factual and statistical report on the TV and radio sector. This year we have structured the findings into four chapters. • The total video chapter looks at trends across all types of video including traditional broadcast TV, video-on-demand services and online video. • In the second chapter, we take a deeper look at public service broadcasting and some wider aspects of broadcast TV. • The third chapter is about online video. This is where we examine in greater depth subscription video on demand and YouTube. -

What Is Bbc Three?

We tested the public value of the proposed changes using a combination of quantitative and qualitative methodologies Quantitative methodology Qualitative methodology We ran a 15 minute online survey with 3,281 respondents to We conducted 20 x 2 hour ‘Extended Group’ sessions via Zoom with understand current associations with BBC Three, the appeal of BBC a mix of different audiences to explore and compare reactions, Three launching as a linear channel, and how this might impact from a personal and societal value perspective, to the concept of existing services in the market. BBC Three becoming a linear channel again. In the survey, we explored the following: In the sessions, we explored the following: - Demographics and brand favourability - Linear TV consumption and BBC attitudes - Current TV and video consumption - (S)VOD consumption behaviours, with a focus on BBC Three - BBC Three awareness, usage and perceptions (current) - A BBC Three content evaluation (via BBC Three on iPlayer exploration) - Likelihood of watching new TV channel and perceptions - Responses to the proposal of BBC Three becoming a TV channel - Impact on services currently used (including time taken away from each) - Expected personal and societal impact of the proposed changes - Societal impact of BBC Three launching as a TV channel - Evaluation of proposed changes against BBC Public Purposes 4 The qualitative stage involved 20 x 2-hour extended digital group discussions across the UK with a carefully designed sample 20 x 2 hour Extended Zoom Groups The qualitative -

Researching Digital on Screen Graphics Executive Sum M Ary

Researching Digital On Screen Graphics Executive Sum m ary Background In Spring 2010, the BBC commissioned independent market research company, Ipsos MediaCT to conduct research into what the general public, across the UK thought of Digital On Screen Graphics (DOGs) – the channel logos that are often in the corner of the TV screen. The research was conducted between 5th and 11th March, with a representative sample of 1,031 adults aged 15+. The research was conducted by interviewers in-home, using the Ipsos MORI Omnibus. The key findings from the research can be found below. Key Findings Do viewers notice DOGs? As one of our first questions we split our sample into random halves and showed both halves a typical image that they would see on TV. One was a very busy image, with a DOG present in the top left corner, the other image had much less going on, again with the DOG in the top left corner. We asked respondents what the first thing they noticed was, and then we asked what they second thing they noticed was. It was clear from the results that the DOGs did not tend to stand out on screen, with only 12% of those presented with the ‘less busy’ screen picking out the DOG (and even fewer, 7%, amongst those who saw the busy screen). Even when we had pointed out DOGs and talked to respondents specifically about them, 59% agreed that they ‘tend not to notice the logos’, with females and viewers over 55, the least likely to notice them according to our survey. -

PSB Output and Spend

B - PSB Output and Spend PSB Report 2012 – Information pack Contents Page • Background 2 • PSB spend 4 • PSB first run originations 14 • UK/national News and Current Affairs 19 • UK/national News 21 • Current Affairs 23 • Non-network output in the nations and English regions 25 • Factual 29 • Factual output by sub-genre 30 • Specialist Factual – peak time first run originated output 31 • Arts, Education and Religion/Ethics 32 • Children’s PSB output and expenditure 35 • Drama, Soap, Sport and Comedy output 38 1 Background (1) • This information pack contains data gathered through Ofcom’s Market Intelligence database in order to provide a picture of the PSB programming and spend over the last five years on PSB channels. • The data in this report are collected by Ofcom from the broadcasters each year, as part of their PSB returns and include figures on the volume of hours broadcast during the year and programme expenditure. Notes on the data • PSB Channels – Where possible data has been provided for BBC One, BBC Two, ITV1, ITV Breakfast, Channel 4, Channel 5 and the BBC’s PSB digital channels: BBC Three, BBC Four, CBBC, Cbeebies, BBC News and BBC Parliament. BBC HD has been excluded from much of the analysis in the report as much of its output is simulcast from the core BBC channels and therefore would represent a disproportionate amount of broadcast hours and spend. Please refer to individual footnotes and chart details indicating when a smaller group of these channels is reported on. ITV1 includes GMTV1 unless otherwise stated. Data for S4C is shown in a separate section, apart from S4C’s children’s output which is included within the children’s section of the report. -

BRITISH ACADEMY TELEVISION CRAFT AWARDS in 2016: Winners in *BOLD

BRITISH ACADEMY TELEVISION CRAFT AWARDS IN 2016: Winners in *BOLD SPECIAL AWARD *NINA GOLD BREAKTHROUGH TALENT sponsored by Sara Putt Associates DC MOORE (Writer) Not Safe for Work- Clerkenwell Films/Channel 4 GUILLEM MORALES (Director) Inside No. 9 - The 12 Days of Christine - BBC Productions/BBC Two MARCUS PLOWRIGHT (Director) Muslim Drag Queens - Swan films/Channel 4 *MICHAELA COEL (Writer) Chewing Gum - Retort/E4 COSTUME DESIGN sponsored by Mad Dog Casting BARBARA KIDD Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell - Cuba Pictures/Feel Films/BBC One *FOTINI DIMOU The Dresser - Playground Television UK Limited, Sonia Friedman Productions, Altus Productions, Prescience/BBC Two JOANNA EATWELL Wolf Hall - Playground Entertainment, Company Pictures/BBC Two MARIANNE AGERTOFT Poldark - Mammoth Screen Limited/BBC One DIGITAL CREATIVITY ATHENA WITTER, BARRY HAYTER, TERESA PEGRUM, LIAM DALLEY I'm A Celebrity... Get Me Out of Here! - ITV Consumer Ltd *DEVELOPMENT TEAM Humans - Persona Synthetics - Channel 4, 4creative, OMD, Microsoft, Fuse, Rocket, Supernatural GABRIEL BISSET-SMITH, RACHEL DE-LAHAY, KENNY EMSON, ED SELLEK The Last Hours of Laura K - BBC MIKE SMITH, FELIX RENICKS, KIERON BRYAN, HARRY HORTON Two Billion Miles - ITN DIRECTOR: FACTUAL ADAM JESSEL Professor Green: Suicide and Me - Antidote Productions/Globe Productions/BBC Three *DAVE NATH The Murder Detectives - Films of Record/Channel 4 JAMES NEWTON The Detectives - Minnow Films/BBC Two URSULA MACFARLANE Charlie Hebdo: Three Days That Shook Paris - Films of Record/More4 DIRECTOR: FICTION sponsored -

Culture, Media and Sport Committee

House of Commons Culture, Media and Sport Committee Future of the BBC Fourth Report of Session 2014–15 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 10 February 2015 HC 315 INCORPORATING HC 949, SESSION 2013-14 Published on 26 February 2015 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Culture, Media and Sport Committee The Culture, Media and Sport Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration and policy of the Department for Culture, Media and Sport and its associated public bodies. Current membership Mr John Whittingdale MP (Conservative, Maldon) (Chair) Mr Ben Bradshaw MP (Labour, Exeter) Angie Bray MP (Conservative, Ealing Central and Acton) Conor Burns MP (Conservative, Bournemouth West) Tracey Crouch MP (Conservative, Chatham and Aylesford) Philip Davies MP (Conservative, Shipley) Paul Farrelly MP (Labour, Newcastle-under-Lyme) Mr John Leech MP (Liberal Democrat, Manchester, Withington) Steve Rotheram MP (Labour, Liverpool, Walton) Jim Sheridan MP (Labour, Paisley and Renfrewshire North) Mr Gerry Sutcliffe MP (Labour, Bradford South) The following Members were also a member of the Committee during the Parliament: David Cairns MP (Labour, Inverclyde) Dr Thérèse Coffey MP (Conservative, Suffolk Coastal) Damian Collins MP (Conservative, Folkestone and Hythe) Alan Keen MP (Labour Co-operative, Feltham and Heston) Louise Mensch MP (Conservative, Corby) Mr Adrian Sanders MP (Liberal Democrat, Torbay) Mr Tom Watson MP (Labour, West Bromwich East) Powers The Committee is one of the Departmental Select Committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. -

Final Determination Annex 2: Channel Take-Up and Substitution

BBC Scotland Competition Assessment Final Determination Annex 2: Channel Take-up and Substitution STATEMENT ANNEX Publication Date: 26 June 2018 BBC Scotland Competition Assessment – Final Determination Annex 2: Channel Take-up and Substitution A2. Channel Take-up and Substitution Introduction A2.1 In order to review the public value and assess the potential impact on fair and effective competition of the BBC’s proposal, we must first consider the audience that the new BBC Scotland channel is likely to attract. This Annex provides our assessment of the likely ’take- up’ of the BBC Scotland channel, i.e. the viewing hours the new channel is likely to attract in Scotland and the viewing share and audience reach it is likely to achieve.1 A2.2 The BBC’s proposal involves associated changes to existing BBC services, in particular BBC Two, BBC Four and CBBC HD in Scotland. We therefore also assess the effect on the viewing of BBC Two, BBC Four and CBBC in Scotland resulting from the BBC’s proposal. A2.3 We then identify the services most likely to be affected by the proposed new channel and the associated changes. We assess the potential audience substitution, including from existing BBC services and commercial services. A2.4 This Annex broadly reflects the assessment of take-up and substitution set out in our Consultation. Where relevant, we have set out the stakeholder views we received in response to our Consultation and how these, along with any further analysis, have influenced our assessment of take-up and substitution. In particular, we set out and respond to stakeholders’ views on: our take-up estimates for the new channel (paragraphs A2.104 to A2.135); and substitution from existing TV channels as a result of the BBC proposal (paragraphs A2.162 to A2.171). -

MGEITF Prog Cover V2

Contents Welcome 02 Sponsors 04 Festival Information 09 Festival Extras 10 Free Clinics 11 Social Events 12 Channel of the Year Awards 13 Orientation Guide 14 Festival Venues 15 Friday Sessions 16 Schedule at a Glance 24 Saturday Sessions 26 Sunday Sessions 36 Fast Track and The Network 42 Executive Committee 44 Advisory Committee 45 Festival Team 46 Welcome to Edinburgh 2009 Tim Hincks is Executive Chair of the MediaGuardian Elaine Bedell is Advisory Chair of the 2009 Our opening session will be a celebration – Edinburgh International Television Festival and MediaGuardian Edinburgh International Television or perhaps, more simply, a hoot. Ant & Dec will Chief Executive of Endemol UK. He heads the Festival and Director of Entertainment and host a special edition of TV’s Got Talent, as those Festival’s Executive Committee that meets five Comedy at ITV. She, along with the Advisory who work mostly behind the scenes in television times a year and is responsible for appointing the Committee, is directly responsible for this year’s demonstrate whether they actually have got Advisory Chair of each Festival and for overall line-up of more than 50 sessions. any talent. governance of the event. When I was asked to take on the Advisory Chair One of the most contentious debates is likely Three ingredients make up a great Edinburgh role last year, the world looked a different place – to follow on Friday, about pay in television. Senior TV Festival: a stellar MacTaggart Lecture, high the sun was shining, the banks were intact, and no executives will defend their pay packages and ‘James Murdoch’s profile and influential speakers, and thought- one had really heard of Robert Peston. -

Media Nations 2020: Scotland Report

Media Nations 2020 Scotland report Published 5 August 2020 Contents Section Overview............................................................................................................ 3 The impact of Covid-19 on audiences and broadcasters .................................... 5 TV services and devices.................................................................................... 12 Broadcast TV viewing ....................................................................................... 16 TV programming for and from Scotland ........................................................... 26 Radio and audio ............................................................................................... 34 2 Overview This Media Nations: Scotland report reviews key trends in the television and audio-visual sector as well as in the radio and audio industry in Scotland. The majority of the research relates to 2019 and early 2020 but, given the extraordinary events that surround the Covid-19 pandemic, Ofcom has undertaken research into how our viewing and news consumption habits have changed during this period. This is explored in the Impact of Covid-19 on audiences and broadcasters section. The report provides updates on several datasets, including bespoke data collected directly from licensed television and radio broadcasters (for output, spend and revenue in 2019), Ofcom’s proprietary consumer research (for audience opinions), and BARB and RAJAR (for audience consumption). In addition to this Scotland report, there are separate -

UK and Non-UK First-Run and Repeat Programming

Annex 2.iii- TV viewing UK and non-UK, first-run and repeat programming: PSB portfolios and multichannels PSB Annual Report December 2014 Contents • Background • Definitions: channel groups • Methodology • Summary – all groups • BBC portfolio group • Channel 4 portfolio group • All other multichannel group 2 Background • This document provides bespoke analysis of viewing data provided by the Broadcasters’ Audience Research Board (BARB). The analysis was undertaken by Attentional Ltd, a registered BARB Bureau. • Attentional maintain a database of BARB programme data, and add to this a number of additional information fields that are not available from standard BARB datasets. These include repeat markings (based on listings data from a number of sources) and country of origin data, based on production company information. This allows BARB viewing data to be combined with custom fields to provide more in-depth analysis of UK broadcast output. • This annex explores the provision of UK broadcast content among non-main PSB channels. It focuses on three groups; the BBC and Channel 4 portfolio of channels and all other remaining multichannels (including ITV and Channel 5 portfolio channels alongside all other broadcasters such as BSkyB and UKTV). Contents • Background • Definitions: channel groups • Methodology • Summary – all groups • BBC portfolio group • Channel 4 portfolio group • All other multichannel group 4 Definitions: Channel groups used in top 100 programmes BBC portfolio channels Channel 4 portfolio channels All Other multichannels -

BBC TV Commissioning Supply Report

BBC TV Commissioning Supply Report 2019 Foreword “BBC Commissioning is at the heart of the UK What we’ve Introduction Production sector – working with the most exciting talent, producers and partners to bring achieved in 2019 brilliant British stories to the screen. I am proud that we have done even more to support Context What we’ve achieved creativity and excellence across the sector this Commissioning bold British content that In 2019 we have strengthened our UK audiences love is what BBC Television creative footprint even further. We have is here to do. We are proud to work with worked with more producers than ever year, and this report sets out what we have world-class production talent across the before, more new producers, more producers whole of the UK – and are committed to based in the Nations and Regions and achieved in 2019.” invest in the next generation to ensure more qualifying independent producers. we continue to do so in the future. We have also increased the scale of Tim Davie Creative success relies on a vibrant our support for new talent and smaller BBC Director-General and diverse production sector – and it companies, particularly outside London is the BBC’s role to support the health and those that have diverse leadership. of the UK supply base at a time of The majority of our programme hours intense global competition. We want are now made by independent producers + producers and talent to continue to and we have increased the levels of see the BBC as a place that nurtures, competition across our content.