Scholars Have Tried Endlessly to Answer This Question

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History of Egypt Under the Ptolemies

UC-NRLF $C lb EbE THE HISTORY OF EGYPT THE PTOLEMIES. BY SAMUEL SHARPE. LONDON: EDWARD MOXON, DOVER STREET. 1838. 65 Printed by Arthur Taylor, Coleman Street. TO THE READER. The Author has given neither the arguments nor the whole of the authorities on which the sketch of the earlier history in the Introduction rests, as it would have had too much of the dryness of an antiquarian enquiry, and as he has already published them in his Early History of Egypt. In the rest of the book he has in every case pointed out in the margin the sources from which he has drawn his information. » Canonbury, 12th November, 1838. Works published by the same Author. The EARLY HISTORY of EGYPT, from the Old Testament, Herodotus, Manetho, and the Hieroglyphieal Inscriptions. EGYPTIAN INSCRIPTIONS, from the British Museum and other sources. Sixty Plates in folio. Rudiments of a VOCABULARY of EGYPTIAN HIEROGLYPHICS. M451 42 ERRATA. Page 103, line 23, for Syria read Macedonia. Page 104, line 4, for Syrians read Macedonians. CONTENTS. Introduction. Abraham : shepherd kings : Joseph : kings of Thebes : era ofMenophres, exodus of the Jews, Rameses the Great, buildings, conquests, popu- lation, mines: Shishank, B.C. 970: Solomon: kings of Tanis : Bocchoris of Sais : kings of Ethiopia, B. c. 730 .- kings ofSais : Africa is sailed round, Greek mercenaries and settlers, Solon and Pythagoras : Persian conquest, B.C. 525 .- Inarus rebels : Herodotus and Hellanicus : Amyrtaus, Nectanebo : Eudoxus, Chrysippus, and Plato : Alexander the Great : oasis of Ammon, native judges, -

VU Research Portal

VU Research Portal The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon Pirngruber, R. 2012 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Pirngruber, R. (2012). The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon: in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 - 140 B.C. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. R. Pirngruber VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. -

Macedonian Kings, Egyptian Pharaohs the Ptolemaic Family In

Department of World Cultures University of Helsinki Helsinki Macedonian Kings, Egyptian Pharaohs The Ptolemaic Family in the Encomiastic Poems of Callimachus Iiro Laukola ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki in auditorium XV, University Main Building, on the 23rd of September, 2016 at 12 o’clock. Helsinki 2016 © Iiro Laukola 2016 ISBN 978-951-51-2383-1 (paperback.) ISBN 978-951-51-2384-8 (PDF) Unigrafia Helsinki 2016 Abstract The interaction between Greek and Egyptian cultural concepts has been an intense yet controversial topic in studies about Ptolemaic Egypt. The present study partakes in this discussion with an analysis of the encomiastic poems of Callimachus of Cyrene (c. 305 – c. 240 BC). The success of the Ptolemaic Dynasty is crystallized in the juxtaposing of the different roles of a Greek ǴdzȅǻǽǷȏȄ and of an Egyptian Pharaoh, and this study gives a glimpse of this political and ideological endeavour through the poetry of Callimachus. The contribution of the present work is to situate Callimachus in the core of the Ptolemaic court. Callimachus was a proponent of the Ptolemaic rule. By reappraising the traditional Greek beliefs, he examined the bicultural rule of the Ptolemies in his encomiastic poems. This work critically examines six Callimachean hymns, namely to Zeus, to Apollo, to Artemis, to Delos, to Athena and to Demeter together with the Victory of Berenice, the Lock of Berenice and the Ektheosis of Arsinoe. Characterized by ambiguous imagery, the hymns inspect the ruptures in Greek thought during the Hellenistic age. -

Johnny Okane (Order #7165245) Introduction to the Hurlbat Publishing Edition

johnny okane (order #7165245) Introduction to the Hurlbat Publishing Edition Weloe to the Hurlat Pulishig editio of Miro Warfare “eries: Miro Ancients This series of games was original published by Tabletop Games in the 1970s with this title being published in 1976. Each game in the series aims to recreate the feel of tabletop wargaming with large numbers of miniatures but using printed counters and terrain so that games can be played in a small space and are very cost-effective. In these new editions we have kept the rules and most of the illustrations unchanged but have modernised the layout and counter designs to refresh the game. These basic rules can be further enhanced through the use of the expansion sets below, which each add new sets of army counters and rules to the core game: Product Subject Additional Armies Expansion I Chariot Era & Far East Assyrian; Chinese; Egyptian Expansion II Classical Era Indian; Macedonian; Persian; Selucid Expansion III Enemies of Rome Britons; Gallic; Goth Expansion IV Fall of Rome Byzantine; Hun; Late Roman; Sassanid Expansion V The Dark Ages Norman; Saxon; Viking Happy gaming! Kris & Dave Hurlbat July 2012 © Copyright 2012 Hurlbat Publishing Edited by Kris Whitmore Contents Introduction to the Hurlbat Publishing Edition ................................................................................................................................... 2 Move Procedures ............................................................................................................................................................................... -

A Literary Sources

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-82860-4 — The Hellenistic World from Alexander to the Roman Conquest 2nd Edition Index More Information Index A Literary sources Livy XXVI.24.7–15: 77 (a); XXIX.12.11–16: 80; XXXI.44.2–9: 11 Aeschines III.132–4: 82; XXXIII.38: 195; XXXVII.40–1: Appian, Syrian Wars 52–5, 57–8, 62–3: 203; XXXVIII.34: 87; 57 XXXIX.24.1–4: 89; XLI.20: 209 (b); ‘Aristeas to Philocrates’ I.9–11 and XLII.29–30.7: 92; XLII.51: 94; 261 V.35–40: XLV.29.3–30 and 32.1–7: 96 15 [Aristotle] Oeconomica II.2.33: I Maccabees 1.1–9: 24; 1.10–25 and 5 7 Arrian, Alexander I.17: ; II.14: ; 41–56: 217; 15.1–9: 221 8 9 III.1.5–2.2: (a); III.3–4: ; II Maccabees 3.1–3: 216 12 13 IV.10.5–12.5: ; V.28–29.1: ; Memnon, FGrH 434 F 11 §§5.7–11: 159 14 20 V1.27.3–5: ; VII.1.1–4: ; Menander, The Sicyonian lines 3–15: 104 17 18 VII.4.4–5: ; VII.8–9 and 11: Menecles of Barca FGrHist 270F9:322 26 Arrian, FGrH 156 F 1, §§1–8: (a); F 9, Pausanias I.7: 254; I.9.4: 254; I.9.5–10: 30 §§34–8: 56; I.25.3–6: 28; VII.16.7–17.1: Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae V.201b–f, 100 258 43 202f–203e: ; VI.253b–f: Plutarch, Agis 5–6.1 and 7.5–8: 69 23 Augustine, City of God 4.4: Alexander 10.6–11: 3 (a); 15: 4 (a); Demetrius of Phalerum, FGrH 228 F 39: 26.3–10: 8 (b); 68.3: cf. -

The Ptolemies: an Unloved and Unknown Dynasty. Contributions to a Different Perspective and Approach

THE PTOLEMIES: AN UNLOVED AND UNKNOWN DYNASTY. CONTRIBUTIONS TO A DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVE AND APPROACH JOSÉ DAS CANDEIAS SALES Universidade Aberta. Centro de História (University of Lisbon). Abstract: The fifteen Ptolemies that sat on the throne of Egypt between 305 B.C. (the date of assumption of basileia by Ptolemy I) and 30 B.C. (death of Cleopatra VII) are in most cases little known and, even in its most recognised bibliography, their work has been somewhat overlooked, unappreciated. Although boisterous and sometimes unloved, with the tumultuous and dissolute lives, their unbridled and unrepressed ambitions, the intrigues, the betrayals, the fratricides and the crimes that the members of this dynasty encouraged and practiced, the Ptolemies changed the Egyptian life in some aspects and were responsible for the last Pharaonic monuments which were left us, some of them still considered true masterpieces of Egyptian greatness. The Ptolemaic Period was indeed a paradoxical moment in the History of ancient Egypt, as it was with a genetically foreign dynasty (traditions, language, religion and culture) that the country, with its capital in Alexandria, met a considerable economic prosperity, a significant political and military power and an intense intellectual activity, and finally became part of the world and Mediterranean culture. The fifteen Ptolemies that succeeded to the throne of Egypt between 305 B.C. (date of assumption of basileia by Ptolemy I) and 30 B.C. (death of Cleopatra VII), after Alexander’s death and the division of his empire, are, in most cases, very poorly understood by the public and even in the literature on the topic. -

The Coins from the Necropolis "Metlata" Near the Village of Rupite

margarita ANDONOVA the coins from the necropolis "metlata" near the village of rupite... THE COINS FROM THE NECROPOLIS METLATA NEAR THE VILLAGE "OF RUPITE" (F. MULETAROVO), MUNICIPALITY OF PETRICH by Margarita ANDONOVA, Regional Museum of History– Blagoevgrad This article sets to describe and introduce known as Charon's fee was registered through the in scholarly debate the numismatic data findspots of the coins on the skeleton; specifically, generated during the 1985-1988 archaeological these coins were found near the head, the pelvis, excavations at one of the necropoleis situated in the left arm and the legs. In cremations in situ, the locality "Metlata" near the village of Rupite. coins were placed either inside the grave or in The necropolis belongs to the long-known urns made of stone or clay, as well as in bowls "urban settlement" situated on the southern placed next to them. It is noteworthy that out of slopes of Kozhuh hill, at the confluence of 167 graves, coins were registered only in 52, thus the Strumeshnitsa and Struma Rivers, and accounting for less than 50%. The absence of now identified with Heraclea Sintica. The coins in some graves can probably be attributed archaeological excavations were conducted by to the fact that "in Greek society, there was no Yulia Bozhinova from the Regional Museum of established dogma about the way in which the History, Blagoevgrad. souls of the dead travelled to the realm of Hades" The graves number 167 and are located (Зубарь 1982, 108). According to written sources, within an area of 750 m². Coins were found mainly Euripides, it is clear that the deceased in 52 graves, both Hellenistic and Roman, may be accompanied to the underworld not only and 10 coins originate from areas (squares) by Charon, but also by Hermes or Thanatos. -

The Antigonids and the Ruler Cult. Global and Local Perspectives?

The Antigonids and the Ruler Cult Global and Local Perspectives? 1 Franca Landucci DOI – 10.7358/erga-2016-002-land AbsTRACT – Demetrius Poliorketes is considered by modern scholars the true founder of ruler cult. In particular the Athenians attributed him several divine honors between 307 and 290 BC. The ancient authors in general consider these honors in a negative perspec- tive, while offering words of appreciation about an ideal sovereignty intended as a glorious form of servitude and embodied in Antigonus Gonatas, Demetrius Poliorketes’ son and heir. An analysis of the epigraphic evidences referring to this king leads to the conclusion that Antigonus Gonatas did not officially encourage the worship towards himself. KEYWORDS – Antigonids, Antigonus Gonatas, Demetrius Poliorketes, Hellenism, ruler cult. Antigonidi, Antigono Gonata, culto del sovrano, Demetrio Poliorcete, ellenismo. Modern scholars consider Demetrius Poliorketes the true founder of ruler cult due to the impressively vast literary tradition on the divine honours bestowed upon this historical figure, especially by Athens, between the late fourth and the early third century BC 2. As evidenced also in modern bib- liography, these honours seem to climax in the celebration of Poliorketes as deus praesens in the well-known ithyphallus dedicated to him by the Athenians around 290 3. Documentation is however pervaded by a tone that is strongly hostile to the granting of such honours. Furthermore, despite the fact that it has been handed down to us through Roman Imperial writers like Diodorus, Plutarch and Athenaeus, the tradition reflects a tendency contemporary to the age of the Diadochi, since these same authors refer, often explicitly, to a 1 All dates are BC, unless otherwise stated. -

Περίληψη : Seleucus I Nicator Was One of the Most Important Kings That Succeeded Alexander the Great

IΔΡΥΜA ΜΕΙΖΟΝΟΣ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΥ Συγγραφή : Σκουνάκη Ιουλία Μετάφραση : Κόρκα Αρχοντή Για παραπομπή : Σκουνάκη Ιουλία , "Seleucus I Nicator", Εγκυκλοπαίδεια Μείζονος Ελληνισμού, Μ. Ασία URL: <http://www.ehw.gr/l.aspx?id=9750> Περίληψη : Seleucus I Nicator was one of the most important kings that succeeded Alexander the Great. Originally a mere member of the corps of the hetaeroi, he became an officer of the Macedonian army and, after taking advantage of the conflict among Alexanderʹs successors, he was proclaimed satrap of Babylonia. After a series of successful diplomatic movements and military victories in the long‑lasting wars against the other Successors, he founded the kingdom and the dynasty of the Seleucids, while he practically revived the empire of Alexander the Great. Άλλα Ονόματα Nicator Τόπος και Χρόνος Γέννησης Europos, 358/354 BC Τόπος και Χρόνος Θανάτου Lysimacheia, 280 BC Κύρια Ιδιότητα Officer of the Macedonian army, satrap of Babylonia (321-316 BC), founder of the kingdom (312 BC) and the dynasty of the Seleucids. 1. Biography Seleucus was born in Macedonia circa 355 BC, possibly in the city of Europos. Pella is also reported to have been his birth city, but that is most likely within the framework of the later propaganda aiming to present Seleucus as the new Alexander the Great.1He was son of Antiochus, a general of Philip II, and Laodice.2 He was about the same age as Alexander the Great and followed him in his campaign in Asia. He was not an important soldier at first, but on 326 BC he led the shieldbearers (hypaspistai)in the battle of the Hydaspes River against the king of India, Porus (also Raja Puru). -

4. Barsine, Daughter of Artabazus

Alexander’s Lovers by Andrew Chugg 4. Barsine, Daughter of Artabazus Barsine was by birth a minor princess of the Achaemenid Empire of the Persians, for her father, Artabazus, was the son of a Great King’s daughter.197 It is known that his father was Pharnabazus, who had married Apame, the daughter of Artaxerxes II, some time between 392 - 387BC.198 Artabazus was a senior Persian Satrap and courtier and was latterly renowned for his loyalty first to Darius, then to Alexander. Perhaps this was the outcome of a bad experience of the consequences of disloyalty earlier in his long career. In 358BC Artaxerxes III Ochus had upon his accession ordered the western Satraps to disband their mercenary armies, but this edict had eventually edged Artabazus into an unsuccessful revolt. He spent some years in exile at Philip’s court during Alexander’s childhood, starting in about 352BC and extending until around 349BC,199 at which time he became reconciled with the Great King. It is likely that his daughter Barsine and the rest of his immediate family accompanied him in his exile, so it is feasible that Barsine knew Alexander when they were both still children. Plutarch relates that she had received a “Greek upbringing”, though in point of fact this education could just as well have been delivered in Artabazus’ Satrapy of Hellespontine Phrygia, where the population was predominantly ethnically Greek. As a young girl, Barsine appears to have married Mentor,200 a Greek mercenary general from Rhodes. Artabazus had previously married the sister of this Rhodian, so Barsine may have been Mentor’s niece. -

The Successors: Alexander's Legacy

The Successors: Alexander’s Legacy November 20-22, 2015 Committee Background Guide The Successors: Alexander’s Legacy 1 Table of Contents Committee Director Welcome Letter ...........................................................................................2 Summons to the Babylon Council ................................................................................................3 The History of Macedon and Alexander ......................................................................................4 The Rise of Macedon and the Reign of Philip II ..........................................................................4 The Persian Empire ......................................................................................................................5 The Wars of Alexander ................................................................................................................5 Alexander’s Plans and Death .......................................................................................................7 Key Topics ......................................................................................................................................8 Succession of the Throne .............................................................................................................8 Partition of the Satrapies ............................................................................................................10 Continuity and Governance ........................................................................................................11 -

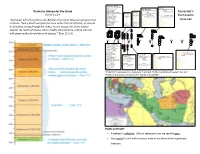

Alexander's Successors

Perdiccas, 323-320 Antigonus (western Asia Minor) 288-285 Antipater (Macedonia) 301, after Ipsus Lysimachus (Anatolia, Thrace) Archon (Babylon) Lysimachus (Anatolia, Thrace) Ptolemy (Egypt) Asander (Caria) Ptolemy (Egypt) Seleucus (Babylonia, N. Syria) Persia to Alexander the Great Atropates (northern Media) 315-311 Alexander’s Seleucus (Babylonia, N. Syria) Eumenes (Cappadocia, Pontus) vs. 318-316 Cassander Cassander (Macedonia) Laomedon (Syria) Lysimachus Daniel 11:1-4 Antigonus Demetrius (Cyprus, Tyre, Demetrius (Macedonia, Cyprus, Leonnatus (Phrygia) Ptolemy Successors Cassander Sidon, Agaean islands) Tyre, Sidon, Agaean islands) Lysimachus (Thrace) Peithon Seleucus Menander (Lydia) Ptolemy Bythinia Bythinia Olympias (Epirus) vs. 332-260 BC Seleucus Epirus Epirus “And now I will tell you the truth. Behold, three more kings are going to arise Peithon (southern Media) Antigonus Greece Greece Philippus (Bactria) vs. Aristodemus Heraclean kingdom Heraclean kingdom Ptolemy (Egypt) Demetrius in Persia. Then a fourth will gain far more riches than all of them; as soon as Eumenes Paeonia Paeonia Stasanor (Aria) Nearchus Olympias Pontus Pontus and others . Peithon Polyperchon Rhodes Rhodes he becomes strong through his riches, he will arouse the whole empire against the realm of Greece. And a mighty king will arise, and he will rule with great authority and do as he pleases.” (Dan 11:2-3) 320 330310 300 290 280 270 260 250 Antipater, 320-319 Alcetas and Attalus (Pisidia ) Antigenes (Susiana) Antigonus (army in Asia) Arrhidaeus (Phrygia) Cassander