January 1, 1992

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABERDEENSHIRE: Atherb, Neolithic Round Barrow ...38, 39 Balbridie, Neolithic Longhouse ...25, 26, 28 Cairn

Index PAGE ABERDEENSHIRE: Balfarg Riding School, Fife, Neolithic site 26, 40, 46 Atherb, Neolithic round barrow ............ 38, 39 Balfarg, Fife, henge ............................... 49 Balbridie, Neolithic longhouse ..............258 2 , 26 , balls, carved stone ................................2 4 . Cairn Catto, Neolithic long barrow ........ 38 BANFFSHIRE: Drum towee housd th , an rf .............eo . 297-356 Cairnborrow, Neolithic long barrow ....... 38 East Finnercy, Neolithic round barrow ... 38 Hill of Foulzie, Neolithic long barrow ..... 38 Knapperty Hillock, Neolithic lon8 g3 barrow Longman Hill, Neolithic long barro8 3 w ..... Midtown of Pitglassie, Neolithic round Tarrieclerack, Neolithic long barro8 3 w ...... cairn ...........................................9 3 , 38 . Barclay, G J, on excavations at Upper Achnacreebeag, Argyll, chambered cairn ... 35 Suisgill, Sutherland ....... 159-98, fiche 1: C1-D4 Agricolan campaigns in Scotland .............. 61-4 Barnetson, Lin, on faunal remains from Aldclune, Blair Atholl, Perthshire, Pictish Bernar Leit, dSt h ............ 424-5 fich : Fl-11 e 1 broochfrom .................................. 233-39 Baroque: Durisdeer Church n unrecoga , - amber beads, from Broch of Burgar .......... 255-6 nized monument ............................ 429-42 amber, medieval ................................... 421,422 beakers ........................................... 131, 1445 14 , e radiocarboth n l Andrewsalo e , V n M , Bennet, Helen & Habib, Vanessa, on tex- dated vegetational history of the Suis- -

FEATURE TYPES Revised 2/2001 Alcove

THE CROW CANYON ARCHAEOLOGICAL CENTER FEATURE TYPES Revised 2/2001 alcove. A small auxiliary chamber in a wall, usually found in pit structures; they often adjoin the east wall of the main chamber and are substantially larger than apertures and niches. aperture. A generic term for a wall opening that cannot be defined more specifically. architectural petroglyph (not on bedrock). A petroglyph in a standing masonry wall.A piece of wall fall with a petroglyph on it should be sent in as an artifact if size permits. ashpit. A pit used primarily as a receptacle for ash removed from a hearth or firepit. In a pit structure, the ash pit is commonly oval or rectangular and is located south of the hearth or firepit. bedrock feature. A feature constructed into bedrock that does not fit any of the other feature types listed here. bell-shaped cist. A large pit whose greatest diameter is substantially larger than the diameter of its opening.A storage function is implied, but the feature may not contain any stored materials, in which case the shape of the pit is sufficient for assigning this feature type. bench surface. The surface of a wide ledge in a pit structure or kiva that usually extends around at least three-fourths of the circumference of the structure and is often divided by pilasters.The southern recess surface is also considered a bench surface segment; each bench surface segment must be recorded as a separate feature. bin: not further specified. An above-ground compartment formed by walling off a portion of a structure or courtyard other than a corner. -

PRESS RELEASE from the FRICK COLLECTION

ARCHIVED PRESS RELEASE from THE FRICK COLLECTION 1 EAST 70TH STREET • NEW YORK • NEW YORK 10021 • TELEPHONE (212) 288-0700 • FAX (212) 628-4417 First Special Presentation on Frick Porcelain in Fifteen Years Rococo Exotic: French Mounted Porcelains and the Allure of the East March 6 through June 10, 2007 In 1915 Henry Clay Frick acquired a magnificent group of eighteenth- century objets d’art to complete the décor of his new home at 1 East 70th Street. Among these was a striking pair of large mounted porcelains, the subject of an upcoming decorative arts focus presentation on view in the Cabinet gallery, the museum’s first ceramics exhibition in fifteen years. Visually splendid, delightfully inventive, and quintessentially French, the jars fuse eighteenth-century French Pair of Deep Blue Chinese Porcelain Jars with French Gilt-Bronze Mounts; porcelain, China, 1st half of the collectors’ love of rare Asian porcelains eighteenth century; gilt-bronze mounts, France, 1745–49; 17 7/8 x 18 5/8 x 10 11/16 in. (45.4 x 47.3 x 27.1 cm) and 18 7/16 x 18 5/8 x 10 5/8 in. (47 x 47.3 x 27 cm); The with their enthusiasm for natural exotica. Frick Collection, New York; photo: Michael Bodycomb Assembled in Paris shortly before 1750, the Frick jars are a hybrid of imported Chinese porcelain and French gilt-bronze mounts in the shape of bulrushes (curling along the handles) and shells, sea fans, corals, and pearls (on the lids). Displayed alongside these objects are French drawings and prints as well as actual seashells and corals, all from New York collections. -

Museum of New Mexico

MUSEUM OF NEW MEXICO OFFICE OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL STUDIES ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE MOGOLLON HIGHLANDS: SETTLEMENT SYSTEMS AND ADAPTATIONS edited by Yvonne R. Oakes and Dorothy A. Zamora VOLUME 6. SYNTHESIS AND CONCLUSIONS Yvonne R. Oakes Submitted by Timothy D. Maxwell Principal Investigator ARCHAEOLOGY NOTES 232 SANTA FE 1999 NEW MEXICO TABLE OF CONTENTS Figures............................................................................iii Tables............................................................................. iv VOLUME 6. SYNTHESIS AND CONCLUSIONS ARCHITECTURAL VARIATION IN MOGOLLON STRUCTURES .......................... 1 Structural Variation through Time ................................................ 1 Communal Structures......................................................... 19 CHANGING SETTLEMENT PATTERNS IN THE MOGOLLON HIGHLANDS ................ 27 Research Orientation .......................................................... 27 Methodology ................................................................ 27 Examination of Settlement Patterns .............................................. 29 Population Movements ........................................................ 35 Conclusions................................................................. 41 REGIONAL ABANDONMENT PROCESSES IN THE MOGOLLON HIGHLANDS ............ 43 Background for Studying Abandonment Processes .................................. 43 Causes of Regional Abandonment ............................................... 44 Abandonment Patterns in the Mogollon Highlands -

The Ninety-Seventh Commencement Asbury Theological Seminary

The Ninety-Seventh Commencement asbury theological seminary Saturday, November 14, 2020 THE NINETY-SEVENTH COMMEncEMENT NOVEMBER 14, 2020 ASBURY THEOLOGIcaL SEMInaRY THE PRESIDENT’S CABINET President TIMOTHY C. TENNENT, PH.D. Provost and Vice President of Academic Affairs DOUGLAS K. MattHEWS, PH.D. Associate Provost and Vice President of Enrollment Management and Student Services KEVIN BISH, M.ED. Vice President of Advancement JAY E. MANSUR, C.F.S. Vice President of Finance and Administration and Chief Financial Officer BRYAN P. BLANKENSHIP, M.B.A. Vice President of Formation DOnna COVINGTON, M.A.C.L. Vice President of Seedbed JOHN DAVID WALT, J.D. Associate Vice President of the Florida Dunnam Campus R. STEPHEN GOBER, D.MIN. Associate Vice President of Enrollment Management and Operations of the Florida Dunnam Campus ERIC CURRIE, M.DIV. AcaDEMIC OFFICERS Associate Provost Dean of Advanced Research Programs CHRIstINE L. JOHNSON, PH.D. LALsanGKIMA PacHUAU, PH.D. Dean of the Beeson School of Practical Theology Dean of the School of Theology and Formation THOMAS F. TUMBLIN, PH.D. JAMES R. THOBABEN, PH.D. Associate Provost and Dean of the Assistant Provost of Institutional Evaluation, Orlando School of Ministry Assessment and Academic Administration BRIAN D. RUSSELL, PH.D. S. BRIAN YEICH, PH.D. Dean of the School of Biblical Interpretation Dean of Library, Information, DAVID R. BAUER, PH.D. and Technology Services PAUL A. TIPPEY, PH.D. Dean of the E. Stanley Jones School of World Mission and Evangelism GREGG A. OKESSON, PH.D. THE NINETY-SEVENTH COMMEncEMENT Saturday, The Fourteenth of November Two Thousand Twenty Eleven o’clock in the morning PRESIDENT TIMOTHY C. -

Empire Under Strain 1770-1775

The Empire Under Strain, Part II by Alan Brinkley This reading is excerpted from Chapter Four of Brinkley’s American History: A Survey (12th ed.). I wrote the footnotes. If you use the questions below to guide your note taking (which is a good idea), please be aware that several of the questions have multiple answers. Study Questions 1. How did changing ideas about the nature of government encourage some Americans to support changing the relationship between Britain and the 13 colonies? 2. Why did Americans insist on “no taxation without representation,” and why did Britain’s leaders find this request laughable? 3. After a quiet period, the Tea Act caused tensions between Americans and Britain to rise again. Why? 4. How did Americans resist the Tea Act, and why was this resistance important? (And there is more to this answer than just the tea party.) 5. What were the “Intolerable” Acts, and why did they backfire on Britain? 6. As colonists began to reject British rule, what political institutions took Britain’s place? What did they do? 7. Why was the First Continental Congress significant to the coming of the American Revolution? The Philosophy of Revolt Although a superficial calm settled on the colonies for approximately three years after the Boston Massacre, the crises of the 1760s had helped arouse enduring ideological challenges to England and had produced powerful instruments for publicizing colonial grievances.1 Gradually a political outlook gained a following in America that would ultimately serve to justify revolt. The ideas that would support the Revolution emerged from many sources. -

Life in the Colonies

CHAPTER 4 Life in the Colonies 4.1 Introduction n 1723, a tired teenager stepped off a boat onto Philadelphia’s Market Street wharf. He was an odd-looking sight. Not having luggage, he had I stuffed his pockets with extra clothes. The young man followed a group of “clean dressed people” into a Quaker meeting house, where he soon fell asleep. The sleeping teenager with the lumpy clothes was Benjamin Franklin. Recently, he had run away from his brother James’s print shop in Boston. When he was 12, Franklin had signed a contract to work for his brother for nine years. But after enduring James’s nasty temper for five years, Franklin packed his pockets and left. In Philadelphia, Franklin quickly found work as a printer’s assistant. Within a few years, he had saved enough money to open his own print shop. His first success was a newspaper called the Pennsylvania Gazette. In 1732, readers of the Gazette saw an advertisement for Poor Richard’s Almanac. An almanac is a book, published annually, that contains information about weather predictions, the times of sunrises and sunsets, planting advice for farmers, and other useful subjects. According to the advertisement, Poor Richard’s Almanac was written by “Richard Saunders” and printed by “B. Franklin.” Nobody knew then that the author and printer were actually the same person. In addition to the usual information contained in almanacs, Franklin mixed in some proverbs, or wise sayings. Several of them are still remembered today. Here are three of the best- known: “A penny saved is a penny earned.” “Early to bed, early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy, and wise.” “Fish and visitors smell in three days.” Poor Richard’s Almanac sold so well that Franklin was able to retire at age 42. -

Native Sons and Daughters Program Manual

NATIVE SONS AND DAUGHTERS PROGRAMS® PROGRAM MANUAL National Longhouse, Ltd. National Longhouse, Ltd. 4141 Rockside Road Suite 150 Independence, OH 44131-2594 Copyright © 2007, 2014 National Longhouse, Ltd. All rights reserved. International copyright secured. No part of this manual may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, now known or hereafter invented, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, xerography, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written consent of National Longhouse, Ltd. Printed in the United States of America EDITORS: Edition 1 - Barry Yamaji National Longhouse, Native Sons And Daughters Programs, Native Dads And Sons, Native Moms And Sons, Native Moms And Daughters are registered trademarks of National Longhouse, Ltd. Native Dads And Daughters, Native Sons And Daughters, NS&D Pathfinders are servicemarks of National Longhouse TABLE of CONTENTS FOREWORD xi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xiii CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1 Why NATIVE SONS AND DAUGHTERS® Programs? 2 What Are NATIVE SONS AND DAUGHTERS® Programs? 4 Program Format History 4 Program Overview 10 CHAPTER 2: ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURES 15 Organizational Levels 16 Administrative Levels 17 National Longhouse, Ltd. 18 Regional Advisory Lodge 21 Local Longhouse 22 Nations 24 Tribes 25 CHAPTER 3: THE TRIBE 29 Preparing for a Tribe Meeting 30 Tribe Meetings 32 iii Table of Contents A Sample Tribe Meeting Procedure 34 Sample Closing Prayers 36 Tips for a Successful Meeting 37 The Parents' Meeting 38 CHAPTER 4: AWARDS, PATCHES, PROGRAM -

Ous 1 Daniel B. Ous Dr. Bouilly Military History Competition

Ous 1 Daniel B. Ous Dr. Bouilly Military History Competition January 6, 2003 The Battle ofValverde Surrounded by the fog of war, Confederate President Jefferson Davis faced mounting challenges to feed and equip his young army. The prospect ofuntapped mineral reserves in the Southwest served as a long shot worthy of speculation. In June 1861, Henry H. Sibley emerged with a grandiose plan that sounded too good to be true. The former Union Army Major impressed the Rebel high command with a campaign to capture the silver and gold in Colorado and California followed by seizing the strategically important West coast (Niderost 11). President Davis did not consider the Southwest an immediate threat compared to the chaos in Richmond and the Southeast. Davis also did not want to invest a lot oftime checking out the character ofSibley or the details ofthe operation, both of which would prove to be a mistake. Davis authorized Sibley the rank ofbrigadier general and sent him to San Antonio to gather a force ofabout 3,500 Texans under the Confederate flag and invade the New Mexico Territory as the first phase ofthe campaign (Kliger 9). Meanwhile, the Union forces in the New Mexico Territory faced serious problems. General Sibley's brother-in-law, Colonel Edward R. S. Canby, took command ofthe New Mexico Department ofthe U.S. Army in June of 1861. A Mexican War hero and seasoned frontier officer, Canby's mission to protect the Southwest took a back seat to main Civil War effort. The War Department reassigned large numbers ofhis enlisted soldiers to the Eastern Theater and Ous2 many of his officers resigned to join the Confederacy. -

Leisure Activities in the Colonial Era

PUBLISHED BY THE PAUL REVERE MEMORIAL ASSOCIATION SPRING 2016 ISSUE NO. 122 Leisure Activities in The Colonial Era BY LINDSAY FORECAST daily tasks. “Girls were typically trained in the domestic arts by their mothers. At an early age they might mimic the house- The amount of time devoted to leisure, whether defined as keeping chores of their mothers and older sisters until they recreation, sport, or play, depends on the time available after were permitted to participate actively.” productive work is completed and the value placed on such pursuits at any given moment in time. There is no doubt that from the late 1600s to the mid-1850s, less time was devoted to pure leisure than today. The reasons for this are many – from the length of each day, the time needed for both routine and complex tasks, and religious beliefs about keeping busy with useful work. There is evidence that men, women, and children did pursue leisure activities when they had the chance, but there was just less time available. Toys and descriptions of children’s games survive as does information about card games, dancing, and festivals. Depending on the social standing of the individual and where they lived, what leisure people had was spent in different ways. Activities ranged from the traditional sewing and cooking, to community wide events like house- and barn-raisings. Men had a few more opportunities for what we might call leisure activities but even these were tied closely to home and business. Men in particular might spend time in taverns, where they could catch up on the latest news and, in the 1760s and 1770s, get involved in politics. -

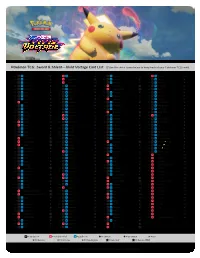

Sword & Shield—Vivid Voltage Card List

Pokémon TCG: Sword & Shield—Vivid Voltage Card List Use the check boxes below to keep track of your Pokémon TCG cards! 001 Weedle ● 048 Zapdos ★H 095 Lycanroc ★ 142 Tornadus ★H 002 Kakuna ◆ 049 Ampharos V 096 Mudbray ● 143 Pikipek ● 003 Beedrill ★ 050 Raikou ★A 097 Mudsdale ★ 144 Trumbeak ◆ 004 Exeggcute ● 051 Electrike ● 098 Coalossal V 145 Toucannon ★ 005 Exeggutor ★ 052 Manectric ★ 099 Coalossal VMAX X 146 Allister ◆ 006 Yanma ● 053 Blitzle ● 100 Clobbopus ● 147 Bea ◆ 007 Yanmega ★ 054 Zebstrika ◆ 101 Grapploct ★ 148 Beauty ◆ 008 Pineco ● 055 Joltik ● 102 Zamazenta ★A 149 Cara Liss ◆ 009 Celebi ★A 056 Galvantula ◆ 103 Poochyena ● 150 Circhester Bath ◆ 010 Seedot ● 057 Tynamo ● 104 Mightyena ◆ 151 Drone Rotom ◆ 011 Nuzleaf ◆ 058 Eelektrik ◆ 105 Sableye ◆ 152 Hero’s Medal ◆ 012 Shiftry ★ 059 Eelektross ★ 106 Drapion V 153 League Staff ◆ 013 Nincada ● 060 Zekrom ★H 107 Sandile ● 154 Leon ★H 014 Ninjask ★ 061 Zeraora ★H 108 Krokorok ◆ 155 Memory Capsule ◆ 015 Shaymin ★H 062 Pincurchin ◆ 109 Krookodile ★ 156 Moomoo Cheese ◆ 016 Genesect ★H 063 Clefairy ● 110 Trubbish ● 157 Nessa ◆ 017 Skiddo ● 064 Clefable ★ 111 Garbodor ★ 158 Opal ◆ 018 Gogoat ◆ 065 Girafarig ◆ 112 Galarian Meowth ● 159 Rocky Helmet ◆ 019 Dhelmise ◆ 066 Shedinja ★ 113 Galarian Perrserker ★ 160 Telescopic Sight ◆ 020 Orbeetle V 067 Shuppet ● 114 Forretress ★ 161 Wyndon Stadium ◆ 021 Orbeetle VMAX X 068 Banette ★ 115 Steelix V 162 Aromatic Energy ◆ 022 Zarude V 069 Duskull ● 116 Beldum ● 163 Coating Energy ◆ 023 Charmander ● 070 Dusclops ◆ 117 Metang ◆ 164 Stone Energy ◆ -

Archeological Findings of the Battle of Apache Pass, Fort Bowie National Historic Site Non-Sensitive Version

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Resource Stewardship and Science Archeological Findings of the Battle of Apache Pass, Fort Bowie National Historic Site Non-Sensitive Version Natural Resource Report NPS/FOBO/NRR—2016/1361 ON THIS PAGE Photograph (looking southeast) of Section K, Southeast First Fort Hill, where many cannonball fragments were recorded. Photograph courtesy National Park Service. ON THE COVER Top photograph, taken by William Bell, shows Apache Pass and the battle site in 1867 (courtesy of William A. Bell Photographs Collection, #10027488, History Colorado). Center photograph shows the breastworks as digitized from close range photogrammatic orthophoto (courtesy NPS SOAR Office). Lower photograph shows intact cannonball found in Section A. Photograph courtesy National Park Service. Archeological Findings of the Battle of Apache Pass, Fort Bowie National Historic Site Non-sensitive Version Natural Resource Report NPS/FOBO/NRR—2016/1361 Larry Ludwig National Park Service Fort Bowie National Historic Site 3327 Old Fort Bowie Road Bowie, AZ 85605 December 2016 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service.