Ous 1 Daniel B. Ous Dr. Bouilly Military History Competition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Archeological Findings of the Battle of Apache Pass, Fort Bowie National Historic Site Non-Sensitive Version

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Resource Stewardship and Science Archeological Findings of the Battle of Apache Pass, Fort Bowie National Historic Site Non-Sensitive Version Natural Resource Report NPS/FOBO/NRR—2016/1361 ON THIS PAGE Photograph (looking southeast) of Section K, Southeast First Fort Hill, where many cannonball fragments were recorded. Photograph courtesy National Park Service. ON THE COVER Top photograph, taken by William Bell, shows Apache Pass and the battle site in 1867 (courtesy of William A. Bell Photographs Collection, #10027488, History Colorado). Center photograph shows the breastworks as digitized from close range photogrammatic orthophoto (courtesy NPS SOAR Office). Lower photograph shows intact cannonball found in Section A. Photograph courtesy National Park Service. Archeological Findings of the Battle of Apache Pass, Fort Bowie National Historic Site Non-sensitive Version Natural Resource Report NPS/FOBO/NRR—2016/1361 Larry Ludwig National Park Service Fort Bowie National Historic Site 3327 Old Fort Bowie Road Bowie, AZ 85605 December 2016 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. -

Special Report Covering the Proposed Fort Union National Monument

-,-------- "·" < \ SPECIAL REPORT COVERING THE PROPOSED FORT UNION NATIONAL MONUMENT Submitted by Region III Headquarters National Park Service Department of the Interior " Santa~Fe, New Mexico June, 1939 \~ • ' . SPECIAL REPORT COVERING THE PROPOSED "-·,: FORT·UNION NATIONAL MONUMENT Submitted . By .. Region III Headque.rters National Park S!lrvice Department· or the Interior . ', '' . :, ·' ' · Santa Fe, New Mexico june, 1939 • • . TJUlL:E OF CONTEN'.l'S I. CRITICAL ANALYSIS O.F Tm; SI'l'E A. · Sy-noP.ais-_ • .--~_-:_~- •.• _.·_. •.•-:•-~::~:,~--. •· ~ _•_ • ~- .-.;·_ ... ,.- ._ •• •· ·-·· l , B •. Accurate Description or the Site •••• , ; • , 2 o• Identification o:f' the Site ...... • ....... 12 D, Historfcal.. Ne.rrati.Va.·: •· •• _.::~.--.:~•"·········•·1·2 :it. Evaluation o~- .the- S~-te •• • ~-· ~ ••. • ..•.•.• • 13 II. PARK DA.TA -A~ Owrier&hip •••••• ~- .• ,~- ••••••• •: . ••.•.••••••• • 14 - B. Apprai~e4 .Value •• • :~... -•• •·• •• ~ ............. • 14 o. Condi'l;ion, including .Previous . _Development •• •. -~--•.·••-•. ~-- •• -.-._. ~ ••••.•• •:• .. _._14 D. Care, including Past, !'resent, and · Probable Fu.ture. •-•••• .. ••••···· , ••••• •.•.•• .,:-15 .E. AOoessib1l1 ty-:.,,. •. ·• .-. _..• :~ .. ;-. -~-~- .•. ·· .. ~--• ~-15 f, l?ossibili~ o:f' Presel"ration •• , •••• , , .•, •• 15 G. · . Bttggest8d t>evel(,pntlnt -~ •·~·. ~ .•· •' • ••.••••.•.. , l·6 H. Relationship or. Site to Areas Already · · Administered.by National Park.Service,,16 APPENDIX MAPS. PHOTOGRAPHS OTf.!ER.EXHIBITS • • . I • . ORITIOAL ANALYSIS OF TEE SITE A. 8ynopsis Fort Union is generally recognized as the outstandiIJ8 historic United States miiitary poet in New Mexico. For four decades, from 1851 to 1891, it pleyed an ilnportant part in the establishment .of. pe~ manent United States rule in the Southwest. Established in 1851 to counteract the·depredations of frontier Indians and to protect the Santa Fe Tra11.1 Fort Union experienced a varie.d existence, Typical of most United States. -

The Battle of Mesilla

The Organ Mountains near Mesilla Civil War In The West - The Battle of Mesilla By Bert Dunkerly Sometimes juxtapositions grab our attention and draw us to see connections. On a recent trip to New Mexico to visit family, my thoughts turned to the Confederate invasion of what was then the Arizona Territory. Living close to the Confederate White House and Virginia State Capitol, it occurred to me how the decisions, plans, and policies enacted there reached the far flung and remote areas of the fledging nation, like Mesilla, New Mexico. In one day, I left the heart of the Confederate government and visited perhaps its farthest outpost in Mesilla. In one location, amid the opulent Executive Mansion, decisions were made, and on the hot, dusty frontier, reality was on the ground. At the time of the war, Mesilla was a village of about 800. The town stood not far from the Rio Grande, along a major north-south trade route that had been used for centuries. After the Mexican War (1846-48), the territory remained part of Mexico, but was purchased by the U.S. in the 1854 Gadsden Purchase. This acquisition was made to allow for construction of a southern transcontinental railroad. On November 16, 1854 the United States flag rose above the plaza in the center of town, solidifying the Gadsden Purchase. Located in the center of the village, the plaza was flanked by several important community buildings, including a church and an adobe courthouse. Today the town is an inviting place, with local shops, galleries, restaurants, and bars. -

The Civil War in New Mexico: Tall Tales and True Spencer Wilson and Robert A

New Mexico Geological Society Downloaded from: http://nmgs.nmt.edu/publications/guidebooks/34 The Civil War in New Mexico: Tall tales and true Spencer Wilson and Robert A. Bieberman, 1983, pp. 85-88 in: Socorro Region II, Chapin, C. E.; Callender, J. F.; [eds.], New Mexico Geological Society 34th Annual Fall Field Conference Guidebook, 344 p. This is one of many related papers that were included in the 1983 NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebook. Annual NMGS Fall Field Conference Guidebooks Every fall since 1950, the New Mexico Geological Society (NMGS) has held an annual Fall Field Conference that explores some region of New Mexico (or surrounding states). Always well attended, these conferences provide a guidebook to participants. Besides detailed road logs, the guidebooks contain many well written, edited, and peer-reviewed geoscience papers. These books have set the national standard for geologic guidebooks and are an essential geologic reference for anyone working in or around New Mexico. Free Downloads NMGS has decided to make peer-reviewed papers from our Fall Field Conference guidebooks available for free download. Non-members will have access to guidebook papers two years after publication. Members have access to all papers. This is in keeping with our mission of promoting interest, research, and cooperation regarding geology in New Mexico. However, guidebook sales represent a significant proportion of our operating budget. Therefore, only research papers are available for download. Road logs, mini-papers, maps, stratigraphic charts, and other selected content are available only in the printed guidebooks. Copyright Information Publications of the New Mexico Geological Society, printed and electronic, are protected by the copyright laws of the United States. -

Fort Fillmore

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 6 Number 4 Article 2 10-1-1931 Fort Fillmore M. L. Crimmins Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Crimmins, M. L.. "Fort Fillmore." New Mexico Historical Review 6, 4 (1931). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol6/iss4/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. NEW MEXICO HISTORICAL REVIEW -'.~'-""----""'-'-'.'~ ... --- _.--'- . .--.~_._ ..._.._----., ...._---_._-_._--- --~----_.__ ..- ... _._._... Vol. VI. OCTOBER, 1931 No.4. --_. -'- ."- ---_._---_._- _._---_._---..--. .. .-, ..- .__.. __ .. _---------- - ------_.__._-_.-_... --- - - .._.....- .. - FORT FILLMORE By COLONEL M. L. CRIMMINS ABOUT thirty-eight miles from El Paso, on the road to Las I"l.. Cruces on Highway No. 80, we pass a sign on the rail road marked "Fort Fillmore." About a mile east of this point are the ruins of old Fort Fillmore, which at one time was an important strategical point on the Mexican border. In 1851, the troops were moved from Camp Concordia, now I El Paso, and established at this point, and the fort was named after President Millard Fillmore. Fdrt Fillmore was about three miles southeast of Mesilla, which at that time was the largest town in the neighborhood, El Paso hav~ng only about thirty Americans and some two hundred Mexicans. -

El Paso Del Norte: a Cultural Landscape History of the Oñate Crossing on the Camino Real De Tierra Adentro 1598 –1983, Ciudad Juárez and El Paso , Texas, U.S.A

El Paso del Norte: A Cultural Landscape History of the Oñate Crossing on the Camino Real de Tierra Adentro 1598 –1983, Ciudad Juárez and El Paso , Texas, U.S.A. By Rachel Feit, Heather Stettler and Cherise Bell Principal Investigators: Deborah Dobson-Brown and Rachel Feit Prepared for the National Park Service- National Trails Intermountain Region Contract GS10F0326N August 2018 EL PASO DEL NORTE: A CULTURAL LANDSCAPE HISTORY OF THE OÑATE CROSSING ON THE CAMINO REAL DE TIERRA ADENTRO 1598–1893, CIUDAD JUÁREZ, MEXICO AND EL PASO, TEXAS U.S.A. by Rachel Feit, Heather Stettler, and Cherise Bell Principal Investigators: Deborah Dobson-Brown and Rachel Feit Draft by Austin, Texas AUGUST 2018 © 2018 by AmaTerra Environmental, Inc. 4009 Banister Lane, Suite 300 Austin, Texas 78704 Technical Report No. 247 AmaTerra Project No. 064-009 Cover photo: Hart’s Mill ca. 1854 (source: El Paso Community Foundation) and Leon Trousset Painting of Ciudad Juárez looking toward El Paso (source: The Trousset Family Online 2017) Table of Contents Table of Contents Chapter 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro ....................................................................................................... 1 1.2 The Oñate Crossing in Context .............................................................................................................. 1 ..................................................................... -

First Battle of Mesilla 1 First Battle of Mesilla

First Battle of Mesilla 1 First Battle of Mesilla The First Battle of Mesilla, fought on July 25, 1861 at Mesilla in what is now New Mexico, was an engagement between Confederate and Union forces during the American Civil War. The battle resulted in a Confederate victory and led directly to the official establishing of a Confederate Arizona Territory, consisting of the southern portion of the New Mexico Territory. The victory paved the way for the Confederate New Mexico Campaign the following year. Background Following the secession of Texas in February 1861 and its joining the Confederacy, a battalion of the 2nd Texas Mounted Rifles under Lieutenant Colonel John R. Baylor was sent to occupy the series of forts along the western Texas frontier which had been abandoned by the Union Army. Baylor's orders from the Department of Texas commander, Colonel Earl Van Dorn, allowed him to advance into New Mexico in order to attack the Union forts along the Rio Grande if he thought the situation called for such measures. Convinced that the Union force at Fort Fillmore would soon attack, Baylor decided to take the initiative and launch an attack of his own. Leaving during the night of July 23, Baylor arrived in Mesilla the next night, preparing to launch a surprise attack the next morning. However, a Confederate deserter informed the fort's commander, Major Isaac Lynde, of the plans. The next day, Baylor led his battalion across the Rio Grande into Mesilla, to the cheers of the population. A company of Arizona Confederates joined Baylor here, and were convinced to muster into the Confederate Army. -

“Doc” Scurlock

ISSN 1076-9072 SOUTHERN NEW MEXICO HISTORICAL REVIEW Pasajero del Camino Real Doña Ana County Historical Society Volume VIII, No.1 Las Cruces, New Mexico January 2001 PUBLISHER Doña Ana County Historical Society EDITOR Robert L. Hart ASSOCIATE EDITOR Rick Hendricks PUBLICATION COMMITTEE Doris Gemoets, Martin Gemoets, Rhonda A. Jackson, Winifred Y, Jacobs, Julia Wilke TYPOGRAPHY, DESIGN, PRINTING lnsta-Copy Printing/Office Supply Las Cruces, New Mexico COVER DRAWING BY Jose Cisneros (Reproduced with permission of the artist) The Southern New Mexico Historical Review (ISSN-1076-9072) is published by the Doña Ana County Historical Society for its members and others interested in the history of the region. The opinions expressed in the articles are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Doña Ana County Historical Society. Articles may be quoted with credit to the author and the Southern New Mexico Historical Review. The per-copy price of the Review is $6.00 ($5.00 to Members). If ordering by mail, please add $2.00 for postage and handling. Correspondence regarding articles for the Southern New Mexico Historical Review may be directed to the Editor at the Doña Ana County Historical Society (500 North Water Street, Las Cruces, NM 88001-1224). Inquiries for society membership also may be sent to this address. Click on Article to Go There Southern New Mexico Historical Review Volume VIII, No. 1 Las Cruces, New Mexico January 2001 ARTICLES The Fort Fillmore Cemetery Richard Wadsworth ............................................................................................................................... -

Fort Union and the Frontier Army in the Southwest

Fort Union NM: Fort Union and the Frontier Army in the Southwest FORT UNION Historic Resource Study Fort Union and the Frontier Army in the Southwest: A Historic Resource Study Fort Union National Monument Fort Union, New Mexico Leo E. Oliva 1993 Southwest Cultural Resources Center Professional Papers No. 41 Divsion of History National Park Service Santa Fe, New Mexico TABLE OF CONTENTS foun/hrs/index.htm Last Updated: 09-Jul-2005 http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/foun/index.htm [9/29/2008 1:57:53 PM] Fort Union NM: Fort Union and the Frontier Army in the Southwest (Table of Contents) FORT UNION Historic Resource Study TABLE OF CONTENTS Cover List of Tables List of Maps List of Illustrations Preface Acknowledgments Abbreviations Used in Footnotes Chapter 1: Before Fort Union Chapter 2: The First Fort Union Chapter 3: Military Operations before the Civil War Chapter 4: Life at the First Fort Union Chapter 5: Fort Union and the Army in New Mexico during the Civil War Chapter 6: The Third Fort Union: Construction and Military Operations, Part One (to 1869) Chapter 7: The Third Fort Union: Construction and Military Operations, Part Two (1869-1891) Chapter 8: Life at the Third Fort Union Chapter 9: Military Supply & the Economy: Quartermaster, Commissary, and Ordnance Departments http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/foun/hrst.htm (1 of 7) [9/29/2008 1:57:56 PM] Fort Union NM: Fort Union and the Frontier Army in the Southwest (Table of Contents) Chapter 10: Fitness and Discipline: Health Care and Military Justice Epilogue -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E2557 HON

December 15, 2005 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E2557 the German POW camp for American officers Salopek, as celebrated in the biography by Duff, a constituent from Rialto, California who where General Patton’s son-in-law also was Gerald Carson, ‘‘Big John’, or 1Lt John passed away on December 11, 2005. I cannot being held. As a result of the ill-fated raid to Salopek, to whom Fort Fillmore is being dedi- begin to express how saddened I am by the liberate the POWs in Hammelburg, all POWs cated today, was born on September 17, 1921 passing of my friend Jim. All men die, but not were evacuated from camp and were forced to in Croatia. At age eight, he arrived in the all men really live; we can honestly say that walk a treacherous journey of 241 miles in United States, settling in Las Cruces, New Jim lived to the fullest. He was a model cit- subzero weather across Germany before their Mexico. izen, veteran, community leader, father, grand- Salopek received a Reserve Officer’s Train- liberation on May 2, 1945. father, and an extraordinary man. Mr. Thompson’s account of his harrowing ing Corps (ROTC) commission in June 1944. experiences at Hammelburg and during this He was assigned to a platoon leader position Jim Duff was born and raised in Bonham, long march is a sobering reminder to readers in 1st Platoon, Company G of the infamous Texas but lived in Rialto, California for many of the sacrifices of our men and women in uni- 42nd ‘‘Rainbow’’ Division, 7th US Army. -

TERRITORIAL NEW MEXICO GENERAL STEPHEN H. KEARNY at the Outbreak of the Mexican War General Stephen H

TERRITORIAL NEW MEXICO GENERAL STEPHEN H. KEARNY At the outbreak of the Mexican War General Stephen H. Kearny was made commander of the Army of the West by President Polk and ordered to lead a 1700 man expeditionary force from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas to occupy New Mexico and California. He quickly accomplished the bloodless conquest of New Mexico on 19 August 1846, ending the brief period of Mexican control over the territory. After spending a little more than a month in Santa Fe as military governor with headquarters in Santa Fe, Kearny decided to continue on to California after ensuring that a civilian government was in place. Early the following year in Kearny's absence New Mexicans mounted their only challenge to American control. In January, 1847, Kearny's appointed Governor, Thomas H. Benton and six others were murdered in Taos. Colonel Sterling Price moved immediately to quash the insurrection. Price led a modest force of 353 men along with four howitzers out of Albuquerque, adding to the size of his force as he marched north up the Rio Grande by absorbing smaller American units into his command. After a series of small engagements, reaching Taos Pueblo on 3 February Price found the insurgents dug in. Over the next two days Price's force shelled the town and surrounded it in an attempt to force surrender. When American artillery finally breached the walls of the, the battle quickly turned into a running fight with American forces chasing down their opponents who attempted to find shelter in the mountains. In all, perhaps as many as one hundred guerillas were killed, while Price suffered the loss of seven men killed and forty-five wounded. -

Atlas of Historic NM Maps Online at Atlas.Nmhum.Org

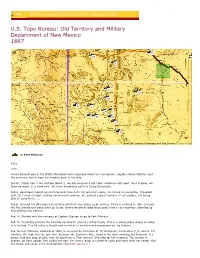

U.S. Topo Bureau: Old Territory and Military Department of New Mexico 1867 11 10 5 6 9 2 12 13 17 4 3 7 15 16 14 1 8 Library of Congress Geography and Map Division - Terms of Use 1: Fort Fillmore 1855 1855 James Bennett was in the White Mountains when Apaches killed his commander, Captain Henry Stanton, and the survivors had to bear his remains back to his wife. Quote: (1855) Feb 2. No mistake about it, we are living on a light diet. Killed our last beef; flour is gone; we have no shoes. It is hard fare. We have decided to call this Camp Starvation. Feb 4. Have been subsisting on horse and mule flesh. No provision came, so started on yesterday. Travelled until 10 o'clock at night, driving our wornout animals. We burned a great number of our saddles, not being able to carry them. ... Feb 8. Crossed the [Manzano] mountains barefoot over sharp rocks and ice. There is nothing to ride. Crossed the Rio Grande and came into Las Lunas, where we are all glad to be once more in our quarters, cleaning up and getting new clothing. Feb 10. Started with the remains of Captain Stanton to go to Fort Fillmore. Feb 15. Yesterday crossed the Jornada del Muerto (Journey of the Dead). This is a sandy place where no water is to be had. It is 90 miles in length and is noted for murders and massacres by the Indians.... Feb 16. Fort Fillmore, established 1853, is occupied by Company B, 1st Dragoons; Companies C, K, and H, 3rd Infantry.