Thesis Submitted to the University of Edinburgh for the Degree-Of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts June , 19 80

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Persian Manuscripts

: SUPPLEMENT TO THE CATALOGUE OF THE PERSIAN MANUSCRIPTS IN THE BRITISH MUSEUM BY CHARLES RIEU, Ph.D. PRINTED BY ORDER OF THE TRUSTEES Sontion SOLD AT THE BRITISH MUSEUM; AND BY Messrs. LONGMANS & CO., 39, Paternoster Row; R QUARITCH, 15, Piccadilly, W.j A. ASHEE & CO., 13, Bedford .Street, Covent Garden ; KEGAN PAUL, TRENCH, TRUBNER & CO., Paternoster House, Charing Cross Eoad ; and HENEY FROWDE, Oxford University Press, Amen Corner. 1895. : LONDON printed by gilbert and rivington, limited , st. John's house, clerkenwell, e.g. TUP r-FTTY CFNTEf ; PEE FACE. The present Supplement deals with four hundred and twenty-five Manuscripts acquired by the Museum during the last twelve years, namely from 1883, the year in which the third and last volume of the Persian Catalogue was published, to the last quarter of the present year. For more than a half of these accessions, namely, two hundred and forty volumes, the Museum is indebted to the agency of Mr. Sidney J. A. Churchill, late Persian Secretary to Her Majesty's Legation at Teheran, who during eleven years, from 1884 to 1894, applied himself with unflagging zeal to the self-imposed duty of enriching the National Library with rare Oriental MSS. and with the almost equally rare productions of the printing press of Persia. By his intimate acquaintance with the language and literature of that country, with the character of its inhabitants, and with some of its statesmen and scholars, Mr. Churchill was eminently qualified for that task, and he availed himself with brilliant success of his exceptional opportunities. His first contribution was a fine illuminated copy of the Zafar Namah, or rhymed chronicle, of Hamdullah Mustaufi (no. -

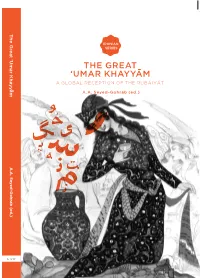

The Great 'Umar Khayyam

The Great ‘Umar Khayyam Great The IRANIAN IRANIAN SERIES SERIES The Rubáiyát by the Persian poet ‘Umar Khayyam (1048-1131) have been used in contemporary Iran as resistance literature, symbolizing the THE GREAT secularist voice in cultural debates. While Islamic fundamentalists criticize ‘UMAR KHAYYAM Khayyam as an atheist and materialist philosopher who questions God’s creation and the promise of reward or punishment in the hereafter, some A GLOBAL RECEPTION OF THE RUBÁIYÁT secularist intellectuals regard him as an example of a scientist who scrutinizes the mysteries of the universe. Others see him as a spiritual A.A. Seyed-Gohrab (ed.) master, a Sufi, who guides people to the truth. This remarkable volume collects eighteen essays on the history of the reception of ‘Umar Khayyam in various literary traditions, exploring how his philosophy of doubt, carpe diem, hedonism, and in vino veritas has inspired generations of poets, novelists, painters, musicians, calligraphers and filmmakers. ‘This is a volume which anybody interested in the field of Persian Studies, or in a study of ‘Umar Khayyam and also Edward Fitzgerald, will welcome with much satisfaction!’ Christine Van Ruymbeke, University of Cambridge Ali-Asghar Seyed-Gohrab is Associate Professor of Persian Literature and Culture at Leiden University. A.A. Seyed-Gohrab (ed.) A.A. Seyed-Gohrab WWW.LUP.NL 9 789087 281571 LEIDEN UNIVERSITY PRESS The Great <Umar Khayyæm Iranian Studies Series The Iranian Studies Series publishes high-quality scholarship on various aspects of Iranian civilisation, covering both contemporary and classical cultures of the Persian cultural area. The contemporary Persian-speaking area includes Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Central Asia, while classi- cal societies using Persian as a literary and cultural language were located in Anatolia, Caucasus, Central Asia and the Indo-Pakistani subcontinent. -

Persian Poetry at the Indian Frontier

Permanent Black Monographs: The ‘Opus 1’ Series Published by PERMANENT BLACK D-28 Oxford Apartments, 11, I.P. Extension, Persian Poetry Delhi 110092 Distributed by at the Indian Frontier ORIENT LONGMAN LTD Bangalore Bhubaneshwar Calcutta Chennai Ernakulam Guwahati Hyderabad Lucknow Mas‘ûd Sa‘d Salmân Mumbai New Delhi Patna of Lahore © PERMANENT BLACK 2000 ISBN 81 7824 009 2 First published 2000 SUNIL SHARMA Typeset in Adobe Garamond by Guru Typograph Technology, New Delhi 110045 Printed by Pauls Press, New Delhi 110020 Contents Acknowledgements ix Transliteration and Abbreviations xi INTRODUCTION 1 1. POETRY AT THE FRONTIER OF EMPIRE 6 A. At the Frontiers of Islam: The Poetics of Ghazâ 7 B. Lahore: The Second Ghaznavid City 14 C. The Life of Mas‘ûd Sa‘d 18 D. Mas‘ûd Sa‘d and Ghaznavid Poetry 26 2. POETS IN EXILE FROM PRIVILEGED SPACES 33 A. The Perils of Being a Court Poet 33 B. The Poetic Memory of Ghazna and Sultan Mahmûd 39 C. Manipulation of History in a Qasida by Mas‘ûd Sa‘d 43 D. Poets Complaining of Ghurbat 47 E. Mas‘ûd Sa‘d between Ghazna and Lahore 56 3. PRACTICING POETRY IN PRISON 68 A. The Genre of Prison Poetry (Habsîyât)68 B. Varieties of Habsîyât 73 viii / Contents C. The Physical State of Being Imprisoned 81 D. The Prisoner’s Lament 86 E. Mas‘ûd Sa‘d’s Use of His Name 102 4. ‘NEW’ GENRES AND POETIC FORMS 107 A. Shahrâshûb: A Catalogue of Youths 107 B. Bârahmâsâs in Persian? 116 C. Mustazâd: A Choral Poem 123 D. -

Stanzaic Poems

CHAPTER 7 STANZAIC POEMS G. van den Berg 1. The Tarjiʿ-band and Tarkib-band Prosody In Persian classical poetry, three different types of stanzaic po- ems can be discerned: the tarjiʿ-band (or tarjiʿ), the tarkib-band (or tarkib), and the mosammat. The first two types are very much alike: both tarjiʿ-band and tarkib-band consist of a varying num- ber of stanzas, formed by a number of rhyming couplets (beyts). Each stanza has a different rhyme, though the same rhyme may occur in more than one stanza. The individual stanzas are followed and interlinked by a separate beyt with an independent rhyme, the so-called vâsete (linker, or the go-between) or band-e sheʿr.1 The two hemistichs (mesrâʿs) making up the vâsete-beyt usually rhyme, but this rhyme stands apart from the rhyme in the stanzas. The Persian term for the stanza without the vâsete is khâne, the term for the stanza including the vâsete is band, though band, con- fusingly, is sometimes also used to denote the vâsete.2 The vâsete and the rhyme which varies per stanza form the main characteris- tics of the tarjiʿ-band and the tarkib-band. The vâsete is usually clearly marked in printed editions of divans as a separate unit, with the hemistichs forming the vâsete-beyt presented one above the other, rather than next to each other. 1 L. P. Elwell-Sutton, The Persian Metres (Cambridge, 1976), p. 256. 2 G. Schoeler, “Neo-Persian Stanzaic Poetry and its Relationship to the Ara- bic Musammaṭ,” in E. Emery, ed., Muwashshah (London, 2006), p. -

When His Father Was Only Nineteen Years of Age

The Turkish cause owes more to Jelal-ud-Din's son Sultan Veled. This son, whose full name was Sultan Veled Beha- * ud-Din Ahmed, was born in the Seljuq city of Larende, in 623 (1226), when his father was only nineteen years of age. His youth was spent in the service of some of the ereatest Sufi teachers of the time, such as Burhan-ud-Din of Tirmiz, Shems-ud-Din of Tebriz and Salah-ud-Din Feridun of Qonya, the last-mentioned of whom gave him his daughter Fatima in marriage. In his Lives of the Sufi Saints, entitled Nefahat-ul-Uns or 'The Breaths of Intimacy,"'^ Jami, the great Persian poet, tells us that when Sultan Veled grew up, he became so like his father that those who did not know them used to take the two for brothers. Jelal-ud-Di'n, who died in 672 (1273-4), was, according to Eflaki, succeeded by Sheykh Husam-ud-Din, who had till then acted as his vicar. On the death of this person in 683 (1284), the generalship ^ of the order passed to Sultan Veled, who continued to expound his father's teachings in what the biographers de- scribe as clear and graceful language till he died, at the age ' is the of the town it is still used in official Larende old name Qaraman ; documents. 2 The 'Intimacy' alluded to in this title is that between God and the mystic. 3 The generalship of the Mevlevi order is still in the family of Mevlana Efendi. The head- Jelal-ud-Din. -

Father of Persian Verse: Rudaki and His Poetry

Father of Persian Verse Iranian Studies Series The Iranian Studies Series publishes high-quality scholarship on various aspects of Iranian civilisation, covering both contemporary and classical cultures of the Persian cultural area. The contemporary Persian-speaking area includes Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Central Asia, while classi- cal societies using Persian as a literary and cultural language were located in Anatolia, Caucasus, Central Asia and the Indo-Pakistani subcontinent. The objective of the series is to foster studies of the literary, historical, reli- gious and linguistic products in Iranian languages. In addition to research monographs and reference works, the series publishes English-Persian criti- cal text-editions of important texts. The series intends to publish resources and original research and make them accessible to a wide audience. Chief Editor: A.A. Seyed-Gohrab (Leiden University) Advisory Board of ISS: F. Abdullaeva (University of Oxford) I. Afshar (University of Tehran) G.R. van den Berg (Leiden University) J.T.P. de Bruijn (Leiden University) N. Chalisova (Russian State University of Moscow) D. Davis (Ohio State University) F.D. Lewis (University of Chicago) L. Lewisohn (University of Exeter, UK) S. McGlinn (Unaffiliated) Ch. Melville (University of Cambridge) D. Meneghini (University of Venice) N. Pourjavady (University of Tehran) Ch. Ruymbeke (University of Cambridge) S. Sharma (Boston University) K. Talattof (University of Arizona) Z. Vesel (CNRS, Paris) R. Zipoli (University of Venice) Father of Persian Verse Rudaki and his Poetry Sassan Tabatabai Leiden University Press Cover design: Tarek Atrissi Design Layout: V3-Services, Baarn ISBN 978 90 8728 092 5 e-ISBN 978 94 0060 016 4 NUR 630 © S. -

Forugh Farrokhzad Persian Poetness and Feminist

Durham E-Theses Forugh farrokhzad Persian poetness and feminist Bharier, Mehri How to cite: Bharier, Mehri (1978) Forugh farrokhzad Persian poetness and feminist, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9817/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk FORUGH FARROKHZAD PERSIAN F03STKSS AND FEMINIST by Mehri Bharier Subaiiitod for the degree of tyaqtej? of Literature In. Persia;? Studies. University of Durhame April 1978. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. )'-ORl)Gll FARROKHZAD; PEKSIAH POETESS AND FEMINIST by T'ehri Bharier ABSTRACT OF THESIS Th:'.s thesis is the first evaluation of the life and work of Forugh Farrokhzacl, a Persian poetess and feminist who died tragically at the age of 32. -

Indian and Persian Prosody and Recitation

Indian and Persian Prosody and Recitation edited by HIROKO NAGASAKI English editing by Ronald I. Kim Saujanya Publications, Delhi 2012 Contents Preface Vll First published in India, 2012 PART ONE I(;) Publisher EARLY INDO-IRANIAN METRES Ancient Iranian Poetic Metres ISBN-I 0 : 81-86561-04-8 Hassan Rezai Baghbidi 3 ISBN-13 : 978-81-86561-04-1 CLASSICAL PERSIAN METRE Basic Principles of Persian Prosody Editor Ayano Sasaki 25 Dr. Hiroko Nagasaki Associate Professor Meter in Classical Persian Narrative Poetry Hindi Language and Literature Zahra Taheri 45 Osaka University, Japan Verbal Rhythm and Musical Rhythm: A Case Study of Iranian Traditional Music Masato Tani 59 Published by Manju Jain Saujanya Publications NEW INDO-ARYAN METRES 165-E, Kamla Nagar, Delhi - 110007 (India) URDU Tel: +91-11-23844541, Fax: +91-1.1-23849007 Email: [email protected] A Note on the 'Hindi' Metre in Urdu Poetry Website: www.saujanyabooks.com Takamitsu Matsumura 73 Dual Trends of Urdu and Punjabi Prosody So Yamane 97 All rights reserved . d stored in or introduced into a retrieval syst~m, or IDNDI No part ot this book may be reproduce '( I t . mechanical photocopying, recordmg, or . fi by any means e ec rome, ' transmitted m any orm ?r . 'on from the publisher of this book. Hindi Metre: Origins and Development otherwise), without the pnor wntten permiSSI Hiroko Nagasaki 107 The Prosody of Kesav Das Printed in India Yoshifumi Mizuno 131 44 Ayano Sasaki faces of the similarity were settled in a circle which maf 'u-liit. !herefore, the~ f -fo- ''i-lon. As Najafi expresses, however, many is the repetitiOn of fourfol o ma ta' d 'n the circles and we have to . -

Premodern Ottoman Poetry

© 2018, V&R unipress GmbH, Göttingen ISBN Print: 9783847108559 – ISBN E-Book: 9783847008552 Ottoman Studies /Osmanistische Studien Band 5 Herausgegeben von Stephan Conermann, Sevgi Ag˘cagül und Gül S¸ en Die Bände dieser Reihe sind peer-reviewed. © 2018, V&R unipress GmbH, Göttingen ISBN Print: 9783847108559 – ISBN E-Book: 9783847008552 Christiane Czygan /Stephan Conermann (eds.) An Iridescent Device: Premodern Ottoman Poetry With 10 figures V&Runipress Bonn University Press © 2018, V&R unipress GmbH, Göttingen ISBN Print: 9783847108559 – ISBN E-Book: 9783847008552 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Veröffentlichungen der Bonn University Press erscheinen im Verlag V&R unipress GmbH. © 2018, V&R unipress GmbH, Robert-Bosch-Breite 6, D-37079 Göttingen Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Das Werk und seine Teile sind urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung in anderen als den gesetzlich zugelassenen Fällen bedarf der vorherigen schriftlichen Einwilligung des Verlages. Umschlagabbildung: Third Divan of Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent, Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg, MKG, 1886.168. Incipit. Fotographer Luther & Fellenberg. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Verlage | www.vandenhoeck-ruprecht-verlage.com ISSN 2366-3677 ISBN 978-3-8470-0855-2 © 2018, V&R unipress GmbH, Göttingen ISBN Print: 9783847108559 – ISBN E-Book: 9783847008552 For Hedda Reindl-Kiel -

Creativity in the Iranian National Tradition

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 1977 Naqqāli and Ferdowsi: Creativity in the Iranian National Tradition Mary Ellen Page University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons, and the Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Page, Mary Ellen, "Naqqāli and Ferdowsi: Creativity in the Iranian National Tradition" (1977). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1531. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1531 This dissertation by Mary Ellen Farr, née Mary Ellen Page, was received in Oriental Studies, a department that no longer exists at Penn and was folded into the Asian and Middle Eastern Studies departments in the 1990s. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1531 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Naqqāli and Ferdowsi: Creativity in the Iranian National Tradition Degree Type Dissertation Degree Name Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) Graduate Group Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations First Advisor William L. Hanaway Subject Categories Comparative Literature | Near and Middle Eastern Studies | Near Eastern Languages and Societies Comments This dissertation by Mary Ellen Farr, née Mary Ellen Page, was received in Oriental Studies, a department that no longer exists at Penn and was folded into the Asian and Middle Eastern Studies departments in the 1990s. This dissertation is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1531 NAQQALI AND FERDOWSI: CREATIVITY IN THE IRANIAN NATIONAL TRADITION Mary Ellen Page A DISSERTATION in Oriental Studies Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Pennsylvani in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Docto of Philosophy. -

The Poetics of Sabk-I Hindi by Shamsur Rahman Faruqi

Stranger in the City: The Poetics of Sabk-i Hindi By Shamsur Rahman Faruqi A Stranger In The City: The Poetics of Sabk-i Hindi by Shamsur Rahman Faruqi 29 C, Hastings Road, Allahabad 211 001, India Phones: 91-532-2622693; 2623137 Email: [email protected] 1 Stranger in the City: The Poetics of Sabk-i Hindi By Shamsur Rahman Faruqi A Stranger In The City: The Poetics of Sabk-i Hindi By Shamsur Rahman Faruqi If there is a knower of tongues here, fetch him; There’s a stranger in the city And he has many things to say. Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib1 (1797-1869) The phrase sabk-i hindi (Indian Style) has long had a faint air of rakish insubordination and unrespectability about it and it is only recently that it has started to evoke comparatively positive feelings.2 However, this change is clearly symptomatic of a process of gentrification and seems to be powered as much by political considerations as by literary ones. Hence the proposal by some scholars to describe the style as “Safavid- Mughal”, or “Isfahani” or plain “Safavid” rather than “Indian.”3 Wheeler Thackston even believes that “there is nothing particularly Indian about the ‘Indian-style’….The more accurate description is ‘High-Period’ style.”4 The term sabk-i hindi was coined perhaps by the Iranian poet, critic, and politician Maliku’sh Shu’ara Muhammad Taqi Bahar (1886-1951) in the first quarter of twentieth century. It signposted a poetry in the Persian language, especially ghazal, written mostly from the sixteenth century onward by Indian and Iranian poets, the latter term to include poets of Iranian origin who spent long periods of their creative life in India. -

Hafiz and the Challenges of Translating Persian Poetry Into

This essay appears in A New Divan: A Lyrical Dialogue between East & West Gingko / 2019 / 9781909942288 Hafi z and the Challenges of Translating Persian Poetry into English narguess farzad Marianne Moore, the renowned modernist American poet who lived most of her life in New York, described the Brooklyn Bridge as ‘a caged Circe of steel and stone’,1 comparing this iconic structure, which connects the boroughs of Brooklyn and Manhattan, to the goddess of wizardry and enchantment. According to Greek legend Circe was skilled in the magic of transfi guration, and she possessed the ability to commu- nicate with the dead to foretell the future. Perhaps this is a good starting defi nition for a literary translator: an illusionist with a dual command of expressiveness and intuition who magically transforms the ‘metaphysical conceits’ of a poet writing in his or her own language, into the appropriate yet pleasing expressions and metaphors of a foreign language, all the while ferrying across as many aspects of the style, idiom and tone of the original as possible. Th e metaphor of the translator as bridge is also an appropriate and fi tting description, even if it has become something of a cliché. Th e translator is expected to establish vital connections between islands of culture, ideas and visceral emotions, regardless of the diff erences in topography and principles of literary composition, especially in the classical period. For such a metaphorical and practical lyrical bridge to withstand the passage of time and stylistic challenges while satisfying the evolving expectations of users, it must be supported by abutments – translators as well as copy-editors who are familiar with cultural idiosyncrasies and traditions of both the source and target languages – who can navigate the incongruous linguistic features on either side of the divide.