Cattle Symbolism in Traditional Irish Folklore, Myth, and Archaeology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stories from Early Irish History

1 ^EUNIVERJ//, ^:IOS- =s & oo 30 r>ETRr>p'S LAMENT. A Land of Heroes Stories from Early Irish History BY W. LORCAN O'BYRNE WITH SIX ILLUSTRATIONS BY JOHN E. BACON BLACKIE AND SON LIMITED LONDON GLASGOW AND DUBLIN n.-a INTEODUCTION. Who the authors of these Tales were is unknown. It is generally accepted that what we now possess is the growth of family or tribal histories, which, from being transmitted down, from generation to generation, give us fair accounts of actual events. The Tales that are here given are only a few out of very many hundreds embedded in the vast quantity of Old Gaelic manuscripts hidden away in the libraries of nearly all the countries of Europe, as well as those that are treasured in the Royal Irish Academy and Trinity College, Dublin. An idea of the extent of these manuscripts may be gained by the statement of one, who perhaps had the fullest knowledge of them the late Professor O'Curry, in which he says that the portion of them (so far as they have been examined) relating to His- torical Tales would extend to upwards of 4000 pages of large size. This great mass is nearly all untrans- lated, but all the Tales that are given in this volume have already appeared in English, either in The Publications of the Society for the Preservation of the Irish Language] the poetical versions of The IV A LAND OF HEROES. Foray of Queen Meave, by Aubrey de Vere; Deirdre', by Dr. Robert Joyce; The Lays of the Western Gael, and The Lays of the Red Branch, by Sir Samuel Ferguson; or in the prose collection by Dr. -

Celtic Solar Goddesses: from Goddess of the Sun to Queen of Heaven

CELTIC SOLAR GODDESSES: FROM GODDESS OF THE SUN TO QUEEN OF HEAVEN by Hayley J. Arrington A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Women’s Spirituality Institute of Transpersonal Psychology Palo Alto, California June 8, 2012 I certify that I have read and approved the content and presentation of this thesis: ________________________________________________ __________________ Judy Grahn, Ph.D., Committee Chairperson Date ________________________________________________ __________________ Marguerite Rigoglioso, Ph.D., Committee Member Date Copyright © Hayley Jane Arrington 2012 All Rights Reserved Formatted according to the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, 6th Edition ii Abstract Celtic Solar Goddesses: From Goddess of the Sun to Queen of Heaven by Hayley J. Arrington Utilizing a feminist hermeneutical inquiry, my research through three Celtic goddesses—Aine, Grian, and Brigit—shows that the sun was revered as feminine in Celtic tradition. Additionally, I argue that through the introduction and assimilation of Christianity into the British Isles, the Virgin Mary assumed the same characteristics as the earlier Celtic solar deities. The lands generally referred to as Celtic lands include Cornwall in Britain, Scotland, Ireland, Wales, and Brittany in France; however, I will be limiting my research to the British Isles. I am examining these three goddesses in particular, in relation to their status as solar deities, using the etymologies of their names to link them to the sun and its manifestation on earth: fire. Given that they share the same attributes, I illustrate how solar goddesses can be equated with goddesses of sovereignty. Furthermore, I examine the figure of St. -

Pilgrimage Stories: the Farmer Fairy's Stone

PILGRIMAGE STORIES: THE FARMER FAIRY’S STONE By Betty Lou Chaika One of the primary intentions of our recent six-week pilgrimage, first to Scotland and then to Ireland, was to visit EarthSpirit sanctuaries in these ensouled landscapes. We hoped to find portals to the Otherworld in order to contact renewing, healing, transformative energies for us all, and especially for some friends with cancer. I wanted to learn how to enter the field of divinity, the aliveness of the EarthSpirit world’s interpenetrating energies, with awareness and respect. Interested in both geology and in our ancestors’ spiritual relationship with Rock, I knew this quest would involve a deeper meeting with rock beings in their many forms. When we arrived at a stone circle in southwest Ireland (whose Gaelic name means Edges of the Field) we were moved by the familiar experience of seeing that the circle overlooks a vast, beautiful landscape. Most stone circles seem to be in places of expansive power, part of a whole sacred landscape. To the north were the lovely Paps of Anu, the pair of breast-shaped hills, both over 2,000 feet high, named after Anu/Aine, the primary local fertility goddess of the region, or after Anu/Danu, ancient mother goddess of the supernatural beings, the Tuatha De Danann. The summits of both hills have Neolithic cairns, which look exactly like erect nipples. This c. 1500 BC stone circle would have drawn upon the power of the still-pervasive earlier mythology of the land as the Mother’s body. But today the tops of the hills were veiled in low, milky clouds, and we could only long for them to be revealed. -

Two Studies on Roman London. Part B: Population Decline and Ritual Landscapes in Antonine London

Two Studies on Roman London. Part B: population decline and ritual landscapes in Antonine London In this paper I turn my attention to the changes that took place in London in the mid to late second century. Until recently the prevailing orthodoxy amongst students of Roman London was that the settlement suffered a major population decline in this period. Recent excavations have shown that not all properties were blighted by abandonment or neglect, and this has encouraged some to suggest that the evidence for decline may have been exaggerated.1 Here I wish to restate the case for a significant decline in housing density in the period circa AD 160, but also draw attention to evidence for this being a period of increased investment in the architecture of religion and ceremony. New discoveries of temple complexes have considerably improved our ability to describe London’s evolving ritual landscape. This evidence allows for the speculative reconstruction of the main processional routes through the city. It also shows that the main investment in ceremonial architecture took place at the very time that London’s population was entering a period of rapid decline. We are therefore faced with two puzzling developments: why were parts of London emptied of houses in the middle second century, and why was this contraction accompanied by increased spending on religious architecture? This apparent contradiction merits detailed consideration. The causes of the changes of this period have been much debated, with most emphasis given to the economic and political factors that reduced London’s importance in late antiquity. These arguments remain valid, but here I wish to return to the suggestion that the Antonine plague, also known as the plague of Galen, may have been instrumental in setting London on its new trajectory.2 The possible demographic and economic consequences of this plague have been much debated in the pages of this journal, with a conservative view of its impact generally prevailing. -

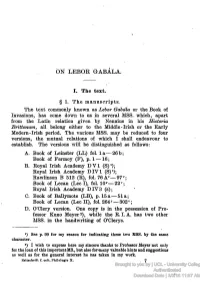

ON LEBOR GABALA. I. the Text

ON LEBOR GABALA. I. The text. § 1. The manuscripts. The text commonly known as Lebor Gabala or the Book of Invasions, has come down to us in several MSS. which, apart from the Latin relation given by Nennius in his Historia Brittomim, all belong either to the Middle-Irish or the Early Modern-Irish period. The various MSS. may be reduced to four versions, the mutual relations of which I shall endeavour to establish. The versions will be distinguished as follows: A. Book of Leinster (LL) fol. la—26b; Book of Fermoy (F), p. 1 —16; B. Royal Irish Academy DVI (S)1); Royal Irish Academy DIV1 (S)1); Rawlinson B 512 (R), fol. 76 Av— 97v; Book of Lecan (Lee I), fol. 10r—22v; Royal Irish Academy DIV3 (s); C. Book of Ballymote (LB), p. 15a—51 a; Book of Lecan (Lee H), fol. 264r—302v; D. OOlery version. One copy is in the possession of Pro- fessor Kuno Meyer2), while the R.I. A. has two other MSS. in the handwriting of O'Clerys. *) See p. 99 for my reason for indicating these two MSS. by the same character. 2) I wish to express here my sincere thanks to Professor Meyer not only for the loan of this important MS., but also formany valuable hints and suggestions as well as for the general interest he has taken in my work. Zeitschrift f. celt. Philologie X. 7 Brought to you by | UCL - University College London Authenticated Download Date | 3/3/16 11:57 AM OS A. G. VAN HAMEL, § 2. -

Lyle Tompsen, Student Number 28001102, Masters Dissertation

Lyle Tompsen, Student Number 28001102, Masters Dissertation The Mari Lwyd and the Horse Queen: Palimpsests of Ancient ideas A dissertation submitted to the University of Wales Trinity Saint David in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Celtic Studies 2012 Lyle Tompsen 1 Lyle Tompsen, Student Number 28001102, Masters Dissertation Abstract The idea of a horse as a deity of the land, sovereignty and fertility can be seen in many cultures with Indo-European roots. The earliest and most complete reference to this deity can be seen in Vedic texts from 1500 BCE. Documentary evidence in rock art, and sixth century BCE Tartessian inscriptions demonstrate that the ancient Celtic world saw this deity of the land as a Horse Queen that ruled the land and granted fertility. Evidence suggests that she could grant sovereignty rights to humans by uniting with them (literally or symbolically), through ingestion, or intercourse. The Horse Queen is represented, or alluded to in such divergent areas as Bronze Age English hill figures, Celtic coinage, Roman horse deities, mediaeval and modern Celtic masked traditions. Even modern Welsh traditions, such as the Mari Lwyd, infer her existence and confirm the value of her symbolism in the modern world. 2 Lyle Tompsen, Student Number 28001102, Masters Dissertation Table of Contents List of definitions: ............................................................................................................ 8 Introduction .................................................................................................................. -

The Ritual Performance and Liminal Bleed of the Beltane Fire Festival, Edinburgh

Please note: this is a final draft version of the manuscript, published in the book Rituals and Traditional Events in the Modern World (2014). Edited by Jennifer Laing and Warwick Frost. Part of the Routledge Advances in Event Research Series: http://www.routledge.com/books/details/9780415707367/ Layers of passage: The ritual performance and liminal bleed of the Beltane Fire Festival, Edinburgh Ross Tinsley (a) Catherine M Matheson (b) a – HTMi, Hotel and Tourism Management Institute Switzerland, 6174 Soerenberg, Kanton Luzern, Switzerland T: +41 (0) 41 488 11 E: [email protected] b – Division of Business, Enterprise and Management, School of Arts, Social Sciences and Management, Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh, Queen Margaret University Drive, Musselburgh, East Lothian EH21 6UU T: +44 (0) 131 474 0000 E: [email protected] Introduction This chapter examines the ritual performance of the Beltane Fire Festival (BFF) which occurs annually on the 30th April on Calton Hill, Edinburgh. The BFF is a contemporary reinterpretation of an ancient Celtic festival celebrating the passage of the seasons. It is a spring festival marking the end of winter and the beginning of summer. As such, the underlying symbolism of the BFF is renewal and rebirth, given the relationship to the passage of the seasons and, furthermore, fertility of people, land and livestock (BFS 2007; Frazer 1922). The contemporary BFF is an interesting context as while it is based on a traditional agrarian and calendrical rite of passage celebrating the passage of a season, it also embodies life-crises style rites of passage for many of the performers in its modern re-interpretation as a liminoid experience (Turner 1975). -

The Dagda As Briugu in Cath Maige Tuired

Deep Blue Deep Blue https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/documents Research Collections Library (University of Michigan Library) 2012-05 Following a Fork in the Text: the Dagda as briugu in Cath Maige Tuired Martin, Scott A. https://hdl.handle.net/2027.42/138967 Downloaded from Deep Blue, University of Michigan's institutional repository Following a Fork in the Text: the Dagda as briugu in Cath Maige Tuired Scott A. Martin, May 2012 The description of the Dagda in §93 of Cath Maige Tuired has become iconic: the giant, slovenly man in a too-short tunic and crude horsehide shoes, dragging a huge club behind him. Several aspects of this depiction are unique to this text, including the language used to describe the Dagda’s odd weapon. The text presents it as a gabol gicca rothach, which Gray translates as a “wheeled fork.” In every other mention of the Dagda’s club – including the other references in CMT (§93 and §119) – the term used is lorg. DIL gives significantly different fields of reference for the two terms: 2 lorg denotes a staff, rod, club, handle of an implement, or “the membrum virile” (thus enabling the scatological pun Slicht Loirge an Dagdai, “Track of the Dagda’s Club/Penis”), while gabul bears a variety of definitions generally attached to the concept of “forking.” The attested compounds for gabul include gabulgicce, “a pronged pole,” with references to both the CMT usage and staves held by Conaire’s swineherds in Togail Bruidne Da Derga. DIL also mentions several occurrences of gabullorc, “a forked or pronged pole or staff,” including an occurrence in TBDD (where an iron gabullorg is carried by the supernatural Fer Caille) and another in Bretha im Fuillema Gell (“Judgements on Pledge-Interests”). -

The Heroic Biography of Cu Chulainn

THE HEROIC BIOGRAPHY OF CU CHULAINN. By Lisa Gibney B.A. NUl MAYNOOTH Ollicoil ni ft£ir«ann Mi ftuid FOR M.A IN MEDIEVAL IRISH HISTORY AND SOURCES, NUI MAYNOOTH, THE DEPARTMENT OF MEDIEVAL IRISH STUDIES, JULY 2004. DEPARTMENT HEAD: MCCONE, K SUPERVISOR: NI BHROLCHAIN,M 60094838 THE HEROIC BIOGRAPHY OF CU CHULAINN. By Lisa Gibney B.A. SPECIAL THANKS TO: Ann Gibney, Claire King, Mary Lenanne, Roisin Morley, Muireann Ni Bhrolchain, Mary Coolen and her team at the Drumcondra Physiotherapy Clinic. CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2 2. Heroic Biography 8 3. Conception and Birth: Compert Con Culainn 18 4. Youth and Life Endangered: Macgnimrada 23 Con Culainn 5. Acquires a wife: Tochmarc Emere 32 6. Visit to Otherworld, Exile and Return: 35 Tochmarc Emere and Serglige Con Culainn 7. Death and Invulnerability: Brislech Mor Maige 42 Muirthemne 8. Conclusion 46 9. Bibliogrpahy 47 i INTRODUCTION Early Irish literature is romantic, idealised, stylised and gruesome. It shows a tension between reality and fantasy ’which seem to me to be usually an irresolvable dichotomy. The stories set themselves in pre-history. It presents these texts as a “window on the iron age”2. The writers may have been Christians distancing themselves from past heathen ways. This backward glance maybe taken from the literature tradition in Latin transferred from the continent and read by Irish scholars. Where the authors “undertake to inform the audience concerning the pagan past, characterizing it as remote, alien and deluded”3 or were they diligent scholars trying to preserve the past. This question is still debateable. The stories manage to be set in both the past and the present, both historical Ireland with astonishingly accuracy and the mythical otherworld. -

ML 4080 the Seal Woman in Its Irish and International Context

Mar Gur Dream Sí Iad Atá Ag Mairiúint Fén Bhfarraige: ML 4080 the Seal Woman in Its Irish and International Context The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Darwin, Gregory R. 2019. Mar Gur Dream Sí Iad Atá Ag Mairiúint Fén Bhfarraige: ML 4080 the Seal Woman in Its Irish and International Context. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42029623 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Mar gur dream Sí iad atá ag mairiúint fén bhfarraige: ML 4080 The Seal Woman in its Irish and International Context A dissertation presented by Gregory Dar!in to The Department of Celti# Literatures and Languages in partial fulfillment of the re%$irements for the degree of octor of Philosophy in the subje#t of Celti# Languages and Literatures (arvard University Cambridge+ Massa#husetts April 2019 / 2019 Gregory Darwin All rights reserved iii issertation Advisor: Professor Joseph Falaky Nagy Gregory Dar!in Mar gur dream Sí iad atá ag mairiúint fén bhfarraige: ML 4080 The Seal Woman in its Irish and International Context4 Abstract This dissertation is a study of the migratory supernatural legend ML 4080 “The Mermaid Legend” The story is first attested at the end of the eighteenth century+ and hundreds of versions of the legend have been colle#ted throughout the nineteenth and t!entieth centuries in Ireland, S#otland, the Isle of Man, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Norway, S!eden, and Denmark. -

Order of Celtic Wolves Lesson 6

ORDER OF CELTIC WOLVES LESSON 6 Introduction Welcome to the sixth lesson. What a fantastic achievement making it so far. If you are enjoying the lessons let like-minded friends know. In this lesson, we are looking at the diet, clothing, and appearance of the Celts. We are also going to look at the complex social structure of the wolves and dispel some common notions about Alpha, Beta and Omega wolves. In the Bards section we look at the tales associated with Lugh. We will look at the role of Vates as healers, the herbal medicinal gardens and some ancient remedies that still work today. Finally, we finish the lesson with an overview of the Brehon Law of the Druids. I hope that there is something in the lesson that appeals to you. Sometimes head knowledge is great for General Knowledge quizzes, but the best way to learn is to get involved. Try some of the ancient remedies, eat some of the recipes, draw principles from the social structure of wolves and Brehon law and you may even want to dress and wear your hair like a Celt. Blessings to you all. Filtiarn Celts The Celtic Diet Athenaeus was an ethnic Greek and seems to have been a native of Naucrautis, Egypt. Although the dates of his birth and death have been lost, he seems to have been active in the late second and early third centuries of the common era. His surviving work The Deipnosophists (Dinner-table Philosophers) is a fifteen-volume text focusing on dining customs and surrounding rituals. -

An Introduction to Brigid Orlagh Costello What Will We Cover?

An Introduction to Brigid Orlagh Costello What will we cover? Pronunciation & spelling Who is Brigid? Practices and customs Practical Exercise Personal gnosis and practices Pronunciation and spelling Brig Bric Brigid Brigit Brighid Bríd Bridget Who is Brigid? Family Tree Cath Maige Tuired Cormac’s Glossary, Daughter(s) of the Dagda The Law Givers The Saint, the Abbess, the Christian times Personal gnosis and practices Family tree Daughter(s) of the Dagda No mother!! Brothers: Aengus Óg, Aed, Cermait Ruadán (Bres’ son, half Formorian, Caith Maigh Tuired) Sons of Tuireann (Brian, Iuchar and Iucharba) Cath Maige Tuired Cath Maige Tuired: The Second Battle of Mag Tuired (Author:[unknown]) section 125 But after the spear had been given to him, Rúadán turned and wounded Goibniu. He pulled out the spear and hurled it at Rúadán so that it went through him; and he died in his father's presence in the Fomorian assembly. Bríg came and keened for her son. At first she shrieked, in the end she wept. Then for the first time weeping and shrieking were heard in Ireland. (Now she is the Bríg who invented a whistle for signalling at night.) Caith Maige Tuired Communication Grief Mother Daughter(s) of the Dagda “Brigit the poetess, daughter of the Dagda, she had Fe and Men, the two royal oxen, from whom Femen is named. She had Triath, king of her boars, from whom Treithirne is named. With them were, and were heard, the three demoniac shouts after rapine in Ireland, whistling and weeping and lamentation.” (source: Macalister, LGE, Vol. 4, p.