The Scale Omnibus 392 Scales for Instrumentalists, Vocalists, Composers and Improvisors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Music Academy, Madras 115-E, Mowbray’S Road

Tyagaraja Bi-Centenary Volume THE JOURNAL OF THE MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS A QUARTERLY DEVOTED TO THE ADVANCEMENT OF THE SCIENCE AND ART OF MUSIC Vol. XXXIX 1968 Parts MV srri erarfa i “ I dwell not in Vaikuntha, nor in the hearts of Yogins, nor in the Sun; (but) where my Bhaktas sing, there be I, Narada l ” EDITBD BY V. RAGHAVAN, M.A., p h .d . 1968 THE MUSIC ACADEMY, MADRAS 115-E, MOWBRAY’S ROAD. MADRAS-14 Annual Subscription—Inland Rs. 4. Foreign 8 sh. iI i & ADVERTISEMENT CHARGES ►j COVER PAGES: Full Page Half Page Back (outside) Rs. 25 Rs. 13 Front (inside) 20 11 Back (Do.) „ 30 „ 16 INSIDE PAGES: 1st page (after cover) „ 18 „ io Other pages (each) „ 15 „ 9 Preference will be given to advertisers of musical instruments and books and other artistic wares. Special positions and special rates on application. e iX NOTICE All correspondence should be addressed to Dr. V. Raghavan, Editor, Journal Of the Music Academy, Madras-14. « Articles on subjects of music and dance are accepted for mblication on the understanding that they are contributed solely o the Journal of the Music Academy. All manuscripts should be legibly written or preferably type written (double spaced—on one side of the paper only) and should >e signed by the writer (giving his address in full). The Editor of the Journal is not responsible for the views expressed by individual contributors. All books, advertisement moneys and cheques due to and intended for the Journal should be sent to Dr. V. Raghavan Editor. Pages. -

Chords and Scales 30/09/18 3:21 PM

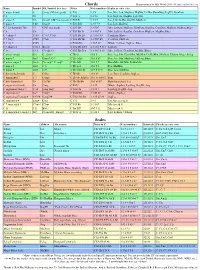

Chords and Scales 30/09/18 3:21 PM Chords Charts written by Mal Webb 2014-18 http://malwebb.com Name Symbol Alt. Symbol (best first) Notes Note numbers Scales (in order of fit). C major (triad) C Cmaj, CM (not good) C E G 1 3 5 Ion, Mix, Lyd, MajPent, MajBlu, DoHar, HarmMaj, RagPD, DomPent C 6 C6 C E G A 1 3 5 6 Ion, MajPent, MajBlu, Lyd, Mix C major 7 C∆ Cmaj7, CM7 (not good) C E G B 1 3 5 7 Ion, Lyd, DoHar, RagPD, MajPent C major 9 C∆9 Cmaj9 C E G B D 1 3 5 7 9 Ion, Lyd, MajPent C 7 (or dominant 7th) C7 CM7 (not good) C E G Bb 1 3 5 b7 Mix, LyDom, PhrDom, DomPent, RagCha, ComDim, MajPent, MajBlu, Blues C 9 C9 C E G Bb D 1 3 5 b7 9 Mix, LyDom, RagCha, DomPent, MajPent, MajBlu, Blues C 7 sharp 9 C7#9 C7+9, C7alt. C E G Bb D# 1 3 5 b7 #9 ComDim, Blues C 7 flat 9 C7b9 C7alt. C E G Bb Db 1 3 5 b7 b9 ComDim, PhrDom C 7 flat 5 C7b5 C E Gb Bb 1 3 b5 b7 Whole, LyDom, SupLoc, Blues C 7 sharp 11 C7#11 Bb+/C C E G Bb D F# 1 3 5 b7 9 #11 LyDom C 13 C 13 C9 add 13 C E G Bb D A 1 3 5 b7 9 13 Mix, LyDom, DomPent, MajBlu, Blues C minor (triad) Cm C-, Cmin C Eb G 1 b3 5 Dor, Aeo, Phr, HarmMin, MelMin, DoHarMin, MinPent, Ukdom, Blues, Pelog C minor 7 Cm7 Cmin7, C-7 C Eb G Bb 1 b3 5 b7 Dor, Aeo, Phr, MinPent, UkDom, Blues C minor major 7 Cm∆ Cm maj7, C- maj7 C Eb G B 1 b3 5 7 HarmMin, MelMin, DoHarMin C minor 6 Cm6 C-6 C Eb G A 1 b3 5 6 Dor, MelMin C minor 9 Cm9 C-9 C Eb G Bb D 1 b3 5 b7 9 Dor, Aeo, MinPent C diminished (triad) Cº Cdim C Eb Gb 1 b3 b5 Loc, Dim, ComDim, SupLoc C diminished 7 Cº7 Cdim7 C Eb Gb A(Bbb) 1 b3 b5 6(bb7) Dim C half diminished Cø -

Year 9 Blues & Improvisation Duration 13-14 Weeks

Topic: Year 9 Blues & Improvisation Duration 13-14 Weeks Key vocabulary: Core knowledge questions Powerful knowledge crucial to commit to long term Links to previous and future topics memory 12-Bar Blues, Blues 45. What are the key features of blues music? • Learn about the history, origins and Links to chromatic Notes from year 8. Chord Sequence, 46. What are the main chords used in the 12-bar blues sequence? development of the Blues and its characteristic Links to Celtic Music from year 8 due to Improvisation 47. What other styles of music led to the development of blues 12-bar Blues structure exploring how a walking using improvisation. Links to form & Syncopation Blues music? bass line is developed from a chord structure from year 9 and Hooks & Riffs Scale Riffs 48. Can you explain the term improvisation and what does it mean progression. in year 9. Fills in blues music? • Explore the effect of adding a melodic Solos 49. Can you identify where the chords change in a 12-bar blues improvisation using the Blues scale and the Make links to music from other cultures Chords I, IV, V, sequence? effect which “swung”rhythms have as used in and traditions that use riff and ostinato- Blues Song Lyrics 50. Can you explain what is meant by ‘Singin the Blues’? jazz and blues music. based structures, such as African Blues Songs 51. Why did music play an important part in the lives of the African • Explore Ragtime Music as a type of jazz style spirituals and other styles of Jazz. -

CARNATIC MUSIC (CODE – 032) CLASS – X (Melodic Instrument) 2020 – 21 Marking Scheme

CARNATIC MUSIC (CODE – 032) CLASS – X (Melodic Instrument) 2020 – 21 Marking Scheme Time - 2 hrs. Max. Marks : 30 Part A Multiple Choice Questions: Attempts any of 15 Question all are of Equal Marks : 1. Raga Abhogi is Janya of a) Karaharapriya 2. 72 Melakarta Scheme has c) 12 Chakras 3. Identify AbhyasaGhanam form the following d) Gitam 4. Idenfity the VarjyaSwaras in Raga SuddoSaveri b) GhanDharam – NishanDham 5. Raga Harikambhoji is a d) Sampoorna Raga 6. Identify popular vidilist from the following b) M. S. Gopala Krishnan 7. Find out the string instrument which has frets d) Veena 8. Raga Mohanam is an d) Audava – Audava Raga 9. Alankaras are set to d) 7 Talas 10 Mela Number of Raga Maya MalawaGoula d) 15 11. Identify the famous flutist d) T R. Mahalingam 12. RupakaTala has AksharaKals b) 6 13. Indentify composer of Navagrehakritis c) MuthuswaniDikshitan 14. Essential angas of kriti are a) Pallavi-Anuppallavi- Charanam b) Pallavi –multifplecharanma c) Pallavi – MukkyiSwaram d) Pallavi – Charanam 15. Raga SuddaDeven is Janya of a) Sankarabharanam 16. Composer of Famous GhanePanchartnaKritis – identify a) Thyagaraja 17. Find out most important accompanying instrument for a vocal concert b) Mridangam 18. A musical form set to different ragas c) Ragamalika 19. Identify dance from of music b) Tillana 20. Raga Sri Ranjani is Janya of a) Karahara Priya 21. Find out the popular Vena artist d) S. Bala Chander Part B Answer any five questions. All questions carry equal marks 5X3 = 15 1. Gitam : Gitam are the simplest musical form. The term “Gita” means song it is melodic extension of raga in which it is composed. -

I. the Term Стр. 1 Из 93 Mode 01.10.2013 Mk:@Msitstore:D

Mode Стр. 1 из 93 Mode (from Lat. modus: ‘measure’, ‘standard’; ‘manner’, ‘way’). A term in Western music theory with three main applications, all connected with the above meanings of modus: the relationship between the note values longa and brevis in late medieval notation; interval, in early medieval theory; and, most significantly, a concept involving scale type and melody type. The term ‘mode’ has always been used to designate classes of melodies, and since the 20th century to designate certain kinds of norm or model for composition or improvisation as well. Certain phenomena in folksong and in non-Western music are related to this last meaning, and are discussed below in §§IV and V. The word is also used in acoustical parlance to denote a particular pattern of vibrations in which a system can oscillate in a stable way; see Sound, §5(ii). For a discussion of mode in relation to ancient Greek theory see Greece, §I, 6 I. The term II. Medieval modal theory III. Modal theories and polyphonic music IV. Modal scales and traditional music V. Middle East and Asia HAROLD S. POWERS/FRANS WIERING (I–III), JAMES PORTER (IV, 1), HAROLD S. POWERS/JAMES COWDERY (IV, 2), HAROLD S. POWERS/RICHARD WIDDESS (V, 1), RUTH DAVIS (V, 2), HAROLD S. POWERS/RICHARD WIDDESS (V, 3), HAROLD S. POWERS/MARC PERLMAN (V, 4(i)), HAROLD S. POWERS/MARC PERLMAN (V, 4(ii) (a)–(d)), MARC PERLMAN (V, 4(ii) (e)–(i)), ALLAN MARETT, STEPHEN JONES (V, 5(i)), ALLEN MARETT (V, 5(ii), (iii)), HAROLD S. POWERS/ALLAN MARETT (V, 5(iv)) Mode I. -

Dance Troupe

DANCE TROUPE The mission of our college ‘Blooming Humanity through Arts’ is disseminated by our institution through the program ‘Dance troupe’ globally for the past 39 years. It started on 27.12.1978 with the classical and folk dances of India and also dance dramas. The 1000th troupe programme was done on 13.01.2002 in the presence of the former Tamilnadu Chief-minister Dr.M.Kalaignar. It is also of great pride to say that soon the dance troupe will be performing its 3000thprogramme. KalaiKaviri performs dances not only to raga and thala but also performs dances with important didactic themes to reach the audience. Dances are performed with the following themes: Spirituality, Humanity, Social development, Moral values, Awareness, Religious morals and Patriotism. The troupe performs mainly in rural and remote areas to create awareness among the public. Irrespective of religion, caste and creed talented students from different backgrounds are selected, trained professionally for the troupe dances. This helps in the growth of the student’s individuality and also showcases their talent. The syllabus and dance items which students learn in their class are highly motivating for them to do a performance in the dance troupe. Main advantages of performing in a dance troupe include losing stage fear, sense of timing and rhythm, learning make-up techniques, costume selection and designing and helps building self-confidence in oneself. A student gets the opportunity to perform different roles and styles for example, classical, Indian folk and drama roles, hence by quick costume and role changes one’s concentration power increases. -

Studies in Instrumentation and Orchestration and in the Recontextualisation of Diatonic Pitch Materials (Portfolio of Compositions)

Studies in Instrumentation and Orchestration and in the Recontextualisation of Diatonic Pitch Materials (Portfolio of Compositions) by Chris Paul Harman Submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Music School of Humanities The University of Birmingham September 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract: The present document examines eight musical works for various instruments and ensembles, composed between 2007 and 2011. Brief summaries of each work’s program are followed by discussions of instrumentation and orchestration, and analysis of pitch organization. Discussions of instrumentation and orchestration explore the composer’s approach to diversification of instrumental ensembles by the inclusion of non-orchestral instruments, and redefinition of traditional hierarchies among instruments in a standard ensemble or orchestral setting. Analyses of pitch organization detail various ways in which the composer renders diatonic -

Lalgudi's Compositions, 21St Century Masterpieces

Lalgudi ’s compositions, 21st century masterpieces - Carnatic Music News - Darbar for cl ... Page 1 of 2 Music Academy to hold singing competion GO Top Most Lalgudi’s compositions, 21st century masterpieces Stories Viewed An engaging dialogue between By Vidya Subramanian www.vidyasubramanian.com flute & mandolin Akademi Ratna for Lalgudi CHENNAI, September 16: My guru, Padmabhushan G.Jayaraman Winning mind share, the Bombay Lalgudi Shri Jayaraman, is one of the most gifted and Jayashri way versatile musicians of this century. His genius has Music is a continuous process innumerable facets. With his warm and self-effacing of learning personality and total commitment to his art, he shares his Music has to be approached deep knowledge with readiness. with modesty Avoid easy route to concert stage Lalgudi Sir is a globally acclaimed musician, composer and When they bow,Ganesh & teacher. His 80th birthday celebration on September 18 Kumaresh sound distinct and September 19, 2010 at The Music Academy, Madras is Understand the science of music Future of voice science in India an event that all of us in the music fraternity are eagerly Listen to Tiruppavai and excitedly looking forward to. Each composition of my guru is a masterpiece in its own right. In this article, I attempt to highlight a few of these gems. Lalgudi Sir has composed in diverse compositional forms. His varnams and tillanas are legendary. He has also composed beautiful pieces in other musical forms such as kirtanams, swarajathis and jathiswarams. The fact that he does not use a mudra or signature term in his compositions bears testimony to his modesty. -

Diploma in Gurmat Sangeet

DIPLOMA IN GURMAT SANGEET ACADEMIC POLICY/ORDINANCES Objectives of the Course : An Online initiative by Gurmat Sangeet Chair - Department of Gurmat Sangeet, Punjabi University, Patiala to disseminate the message of Sikh Gurus through Gurmukhi, Gurmat Studies and Gurmat Sangeet at global level. Duration of the Course : Two Semester Eligibility : The candidate must have passed Certificate Course in Gurmat Sangeet in the same stream Medium of Instruction : English & Punjabi Medium of Examination : English & Punjabi Fees for the Course : On admission in the course a candidate shall have to pay Admission fees (including Examination Fee) as given below Admission Fee : 300US$ (15,000/- INR) upto 30th June st With Late Fee 350US$ (17,500/- INR) upto 31 July With Late Fee 450US$ (22,500/- INR) and with the st special permission of Vice Chancellor upto 31 August SCHEME OF THE COURSE FOR SPRING SEMESTER Compulsory/ Papers Paper Code Title of the Papers Elective Compulsory Paper I DGS 301 Historical Study of Sikhism Papers Paper III DGS 302 Gurbani Santhya DGS 303 Musicology of Gurmat Sangeet Vocal Tradition Elective Paper II DGS 304 Musicology of Gurmat Sangeet String Instrumental Tradition Papers DGS 305 Musicology of Gurmat Sangeet Percussion Instrumental Tradition (Jorhi/Tabla) DGS 306 Stage Performance of Shabad Keertan Elective Paper IV DGS 307 Stage Performance of String Instruments Papers DGS 308 Stage Performance of Percussion Instrumental (Jorhi/Tabla) 1 HISTORICAL STUDY OF SIKHISM (Paper I - DGS 301) 1. Contribution of Ten Guru in Propagation of Sikhism 2. Contributors of Bhai Mardana ji, Baaba Budha ji, Bhai Gurdas ji, and Bhai Nand lal ji in Sikh History. -

Musical Narrative As a Tale of the Forest in Sibelius's Op

Musical Narrative as a Tale of the Forest in Sibelius’s Op. 114 Les Black The unification of multi-movement symphonic works was an important idea for Sibelius, a fact revealed in his famous conversation with Gustav Mahler in 1907: 'When our conversation touched on the essence of the symphony, I maintained that I admired its strictness and the profound logic that creates an inner connection between all the motifs.'1 One might not expect a similar network of profoundly logical connections to exist in sets of piano miniatures, pieces he often suggested were moneymaking potboilers. However, he did occasionally admit investing energy into these little works, as in the case of this diary entry from 25th July 1915: "All these days have gone up in smoke. I have searched my heart. Become worried about myself, when I have to churn out these small lyrics. But what other course do I have? Even so, one can do these things with skill."2 While this admission might encourage speculation concerning the quality of individual pieces, unity within groups of piano miniatures is influenced by the diverse approaches Sibelius employed in composing these works. Some sets were composed in short time-spans, and in several cases included either programmatic titles or musical links that relate the pieces. Others sets were composed over many years and appear to have been compiled simply to satisfied the demands of a publisher. Among the sets with programmatic links are Op. 75, ‘The Trees’, and Op. 85, ‘The Flowers’. Unifying a set through a purely musical device is less obvious, but one might consider his very first group of piano pieces, the Op. -

How to Incorporate Bebop Into Your Improvisation by Austin Vickrey Discussion Topics

How to Incorporate Bebop into Your Improvisation By Austin Vickrey Discussion Topics • Bebop Characteristics & Style • Scales & Arpeggios • Exercises & Patterns • Articulations & Accents • Listening Bebop Characteristics & Style • Developed in the early to mid 1940’s • Medium to fast tempos • Rapid chord progressions / changes • Instrumental “virtuosity” • Simple to complex harmony - altered chords / substitutions • Dominant syncopation of rhythms • New melodies over existing chord changes - Contrafacts Scales & Arpeggios • Scales and arpeggios are the building blocks for harmony • Use of the half-step interval and rapid arpeggiation are characteristic of bebop playing • Because bebop is often played at a fast tempo with rapidly changing chords, it’s crucial to practice your scales and arpeggios in ALL KEYS! Scales & Arpeggios • Scales you should be familiar with: • Major Scale - Pentatonic: 1, 2, 3, 5, 6 • Minor Scales - Pentatonic: 1, b3, 4, 5, b7; Natural Minor, Dorian Minor, Harmonic Minor, Melodic Minor • Dominant Scales - Mixolydian Mode, Bebop Scales, 5th Mode of Harmonic Minor (V7b9), Altered Dominant / Diminished Whole Tone (V7alt, b9#9b13), Dominant Diminished / Diminished starting with a half step (V7b9#9 with #11, 13) • Half-diminished scale - min7b5 (7th mode of major scale) • Diminished Scale - Starting with a whole step (WHWHWHWH) Scales & Arpeggios • Chords and Arpeggios to work in all keys: • Major triad, Maj6/9, Maj7, Maj9, Maj9#11 • Minor triad, m6/9, m7, m9, m11, minMaj7 • Dominant 7ths • Natural extensions - 9th, 13th -

SMPC 2011 Attendees

Society for Music Perception and Cognition August 1114, 2011 Eastman School of Music of the University of Rochester Rochester, NY Welcome Dear SMPC 2011 attendees, It is my great pleasure to welcome you to the 2011 meeting of the Society for Music Perception and Cognition. It is a great honor for Eastman to host this important gathering of researchers and students, from all over North America and beyond. At Eastman, we take great pride in the importance that we accord to the research aspects of a musical education. We recognize that music perception/cognition is an increasingly important part of musical scholarship‐‐and it has become a priority for us, both at Eastman and at the University of Rochester as a whole. This is reflected, for example, in our stewardship of the ESM/UR/Cornell Music Cognition Symposium, in the development of several new courses devoted to aspects of music perception/cognition, in the allocation of space and resources for a music cognition lab, and in the research activities of numerous faculty and students. We are thrilled, also, that the new Eastman East Wing of the school was completed in time to serve as the SMPC 2011 conference site. We trust you will enjoy these exceptional facilities, and will take pleasure in the superb musical entertainment provided by Eastman students during your stay. Welcome to Rochester, welcome to Eastman, welcome to SMPC 2011‐‐we're delighted to have you here! Sincerely, Douglas Lowry Dean Eastman School of Music SMPC 2011 Program and abstracts, Page: 2 Acknowledgements Monetary