TEACHING IMAGE PATTERNS in HAMLET HILARY SEMPLE, Former Lecturer at the University of the Witwatersrand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Tragedy of Hamlet

THE TRAGEDY OF HAMLET THE WORKS OF SHAKESPEARE THE TRAGEDY OF HAMLET EDITED BY EDWARD DOWDEN n METHUEN AND CO. 36 ESSEX STREET: STRAND LONDON 1899 9 5 7 7 95 —— CONTENTS PAGE Introduction ix The Tragedy of Hamlet i Appendix I. The "Travelling" of the Players. 229 Appendix II.— Some Passages from the Quarto of 1603 231 Appendix III. Addenda 235 INTRODUCTION This edition of Hamlet aims in the first place at giving a trustworthy text. Secondly, it attempts to exhibit the variations from that text which are found in the primary sources—the Quarto of 1604 and the Folio of 1623 — in so far as those variations are of importance towards the ascertainment of the text. Every variation is not recorded, but I have chosen to err on the side of excess rather than on that of defect. Readings from the Quarto of 1603 are occa- sionally given, and also from the later Quartos and Folios, but to record such readings is not a part of the design of this edition. 1 The letter Q means Quarto 604 ; F means Folio 1623. The dates of the later Quartos are as follows: —Q 3, 1605 161 1 undated 6, For ; Q 4, ; Q 5, ; Q 1637. my few references to these later Quartos I have trusted the Cambridge Shakespeare and Furness's edition of Hamlet. Thirdly, it gives explanatory notes. Here it is inevitable that my task should in the main be that of selection and condensation. But, gleaning after the gleaners, I have perhaps brought together a slender sheaf. -

The 'Language of Flowers' As Subtext: Conflicted Messages of Domesticity

Working Papers on Design © University of Hertfordshire. To cite this journal article: Sheley, Nancy Strow (2007) ‘The “Language of Flowers” as Coded Subtext: Conflicted Messages of Domesticity in Mary Wilkins Freeman’s Short Fiction’, Working Papers on Design 2 Retrieved <date> from <http://www.herts.ac.uk/artdes1/research/papers/ wpdesign/wpdvol2/vol2.html> ISSN 1470-5516 The ‘Language of Flowers’ as Coded Subtext: Conflicted Messages of Domesticity in Mary Wilkins Freeman’s Short Fiction Nancy Strow Sheley, Ph.D. California State University, Long Beach Abstract This paper presents a unique, literary model for illustrating the symbiotic relationship of text, narrative and image. The examples in this paper are primarily drawn from a selection of popular short fiction by Mary Wilkins Freeman (1852-1930) to suggest that contemporary readers often overlook the nineteenth-century cultural phenomenon, the Language of Flowers. Further, this paper argues that knowledge of this socially constructed vocabulary, extensively detailed in floral dictionaries and other material culture in the nineteenth century, is necessary for fully enhanced readings of texts written by Freeman and other American writers of that time. In the latter half of the 1800s, the mere allusion to a blossom or plant in text could trigger a mental processing of flower to image to definition. Today, those readers who acknowledge the Language of Flowers and understand its use as a subtext can explore how botanical references, even in fiction, often support multiple interpretations of character, setting, plot, and theme. Those who do not understand the coded subtext of the Language of Flowers fail to analyze the literature to its fullest. -

The Language of Flowers Is Almost As Ancient and Universal a One As That of Speech

T H E LANGUAGE OF FLOWERS; OR, FLORA SYMBOLIC A. INCLUDING FLORAL POETRY, ORIGINAL AND SELECTED. BY JOHN INGRAM. “ Then took he up his garland, And did shew what every flower did signify.” Philaster. Beaumont and Fletcher. WITH ORIGINAL ILLUSTRATIONS, PRINTED IN COLOURS BY TERRY. LONDON AND NEW YORK: FREDERICK WARNE AND CO. 1887. vA^tT Q-R 7 SO XSH mi TO Eliza Coo k THIS VOLUME IS AFFECTIONATELY INSCRIBED BY HER FRIEND THE AUTHOR. o Preface. j^IIE LANGUAGE OF FLOWERS has probably called forth as many treatises in explanation of its few and simple rules as has any other mode of communicating ideas; but I flatter myself that this book will be found to be the most complete work on the subject ever published—at least, in this country. I have thoroughly sifted, condensed, and augmented the productions of my many predecessors, and have endeavoured to render the present volume in every re¬ spect worthy the attention of the countless votaries which this “ science of sweet things ” attracts ; and, although I dare not boast that I have exhausted the subject, I may certainly affirm that followers will find little left to glean in the paths that I have traversed. As I have made use of the numerous anecdotes, legends, and poetical allusions herein contained, so Preface. VI have I acknowledged the sources whence they came. It there¬ fore only remains for me to take leave of my readers, with the hope that they will pardon my having detained them so long over a work of this description , but “Unheeded flew the hours, For softly falls the foot of Time That only treads on flowers.” J. -

Shakespeare for Life

Hamlet By William Shakespeare This lesson was inspired by the Macmillan Readers adaption of William Shakespeare’s original playscript. The language has been adapted and graded to make it suitable for readers at Intermediate level. It also features extracts of key speeches from the original text along with explanatory notes, plus glossaries and exercises designed to reinforce understanding post reading. The book is available with CD, as an audio book and as an eBook. Find out more here. • Order print books • Buy eBooks shakespeare for life www.macmillanreaders.com/shakespeare ©2016 Macmillan Education Hamlet TEACHEr’s NOTES LESSON OVERVIEW Level: Intermediate Length: Approximately 40 minutes Language focus: Expressions from Shakespeare’s Hamlet Learning objectives: In this lesson students complete a series of tasks that will help them to build their vocabulary and speaking skills. Students will have the chance to: • Gain an overview of the story of Hamlet and its characters • Learn a series of expressions from the play still in use today • Discuss ghosts and the supernatural and build related vocabulary • Read, analyse and practise reciting a famous speech from the play ContentS • Activity 1: Shakespeare’s Language • Activity 2: Speak Shakespeare Additional Activities: • Themed Discussion • Vocabulary Task HAMLET: TEACHER’S NOTES HAMLET: TEACHER’S shakespeare for life www.macmillanreaders.com/shakespeare ©2016 Macmillan Education Hamlet OVERVIEW OF the PLAy Key themes: Mortality, madness, ghosts, the supernatural and revenge Key characters: • Hamlet: The tragic hero of the play. Hamlet is Prince of Denmark and the son of Queen Gertrude and the late King Hamlet. Bitter and cynical and full of hatred for his Uncle Claudius. -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

Poison and Revenge in Seventeenth Century English Drama

"Revenge Should Have No Bounds": Poison and Revenge in Seventeenth Century English Drama The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Woodring, Catherine. 2015. "Revenge Should Have No Bounds": Poison and Revenge in Seventeenth Century English Drama. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:17463987 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA “Revenge should have no bounds”: Poison and Revenge in Seventeenth Century English Drama A dissertation presented by Catherine L. Reedy Woodring to The Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of English Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2015 © 2015 – Catherine L. Reedy Woodring All rights reserved. Professor Stephen Greenblatt Catherine L. Reedy Woodring “Revenge should have no bounds”: Poison and Revenge in Seventeenth Century English Drama Abstract The revenge- and poison- filled tragedies of seventeenth century England astound audiences with their language of contagion and disease. Understanding poison as the force behind epidemic disease, this dissertation considers the often-overlooked connections between stage revenge and poison. Poison was not only a material substance bought from a foreign market. It was the subject of countless revisions and debates in early modern England. Above all, writers argued about poison’s role in the most harrowing epidemic disease of the period, the pestilence, as both the cause and possible cure of this seemingly contagious disease. -

Shakespeare - Shylock - Mitterwurzer

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Wissenschaftliches Jahrbuch der Tiroler Landesmuseen Jahr/Year: 2016 Band/Volume: 9 Autor(en)/Author(s): Rabanser Hansjörg Artikel/Article: Shakespeare - Shylock - Mitterwurzer. Eine Tirolensie zum 400. Todestag von William Shakespeare 197-231 © Tiroler Landesmuseum Ferdinandeum, Innsbruck download unter www.zobodat.at Abb. 1: Theaterfigurine: Friedrich Mitterwurzer als Jude Shylock. Kolorierte Tuschfederzeichnung von Recht, 1875. TLMF, Bibliothek: W 24244. Foto: TLM. © Tiroler Landesmuseum Ferdinandeum, Innsbruck download unter www.zobodat.at SHAKESPEARE – SHYLOCK – MITTERWURZER. EINE TIROLENSIE ZUM 400. TODESTAG VON WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE Hansjörg Rabanser ABSTRACT Samstag, 23. April 1616: Nach längerer Bewusstlosigkeit aufgrund eines diabetischen Komas stirbt in Madrid der In 1875 the actor Friedrich Mitterwurzer (1844–1897) played Schriftsteller Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra (1547–1616), the part of the Jew Shylock in a performance of „The Mer- der kurz darauf im Convento de las Trinitarias Descalzas de chant of Venice“ by William Shakespeare (1564–1616) at San Ildefonso bestattet wird. Bis heute gilt er als spanischer the Burgtheater in Vienna. The library of the Tiroler Landes- Nationaldichter, der zumindest mit einem Werk seines museum Ferdinandeum has in its collection a drawing that reichhaltigen Œuvres die Unsterblichkeit erreicht hat: „El portrays Mitterwurzer in this role. ingenioso hidalgo Don Quixote de la Mancha“ (1608), der This object marks the starting point of a closer investiga- parodistischen Geschichte des Don Quijote von der Mancha, tion of the early reception of Shakespeare and his works des Ritters von der traurigen Gestalt.1 in German speaking countries, especially Tyrol, where Dienstag, 23. -

1 Shakespeare and Film

Shakespeare and Film: A Bibliographic Index (from Film to Book) Jordi Sala-Lleal University of Girona [email protected] Research into film adaptation has increased very considerably over recent decades, a development that coincides with postmodern interest in cultural cross-overs, artistic hybrids or heterogeneous discourses about our world. Film adaptation of Shakespearian drama is at the forefront of this research: there are numerous general works and partial studies on the cinema that have grown out of the works of William Shakespeare. Many of these are very valuable and of great interest and, in effect, form a body of work that is hybrid and heterogeneous. It seems important, therefore, to be able to consult a detailed and extensive bibliography in this field, and this is the contribution that we offer here. This work aims to be of help to all researchers into Shakespearian film by providing a useful tool for ordering and clarifying the field. It is in the form of an index that relates the bibliographic items with the films of the Shakespearian corpus, going from the film to each of the citations and works that study it. Researchers in this field should find this of particular use since they will be able to see immediately where to find information on every one of the films relating to Shakespeare. Though this is the most important aspect, this work can be of use in other ways since it includes an ordered list of the most important contributions to research on the subject, and a second, extensive, list of films related to Shakespeare in order of their links to the various works of the canon. -

Hamlet (The New Cambridge Shakespeare, Philip Edwards Ed., 2E, 2003)

Hamlet Prince of Denmark Edited by Philip Edwards An international team of scholars offers: . modernized, easily accessible texts • ample commentary and introductions . attention to the theatrical qualities of each play and its stage history . informative illustrations Hamlet Philip Edwards aims to bring the reader, playgoer and director of Hamlet into the closest possible contact with Shakespeare's most famous and most perplexing play. He concentrates on essentials, dealing succinctly with the huge volume of commentary and controversy which the play has provoked and offering a way forward which enables us once again to recognise its full tragic energy. The introduction and commentary reveal an author with a lively awareness of the importance of perceiving the play as a theatrical document, one which comes to life, which is completed only in performance.' Review of English Studies For this updated edition, Robert Hapgood Cover design by Paul Oldman, based has added a new section on prevailing on a draining by David Hockney, critical and performance approaches to reproduced by permission of tlie Hamlet. He discusses recent film and stage performances, actors of the Hamlet role as well as directors of the play; his account of new scholarship stresses the role of remembering and forgetting in the play, and the impact of feminist and performance studies. CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS www.cambridge.org THE NEW CAMBRIDGE SHAKESPEARE GENERAL EDITOR Brian Gibbons, University of Munster ASSOCIATE GENERAL EDITOR A. R. Braunmuller, University of California, Los Angeles From the publication of the first volumes in 1984 the General Editor of the New Cambridge Shakespeare was Philip Brockbank and the Associate General Editors were Brian Gibbons and Robin Hood. -

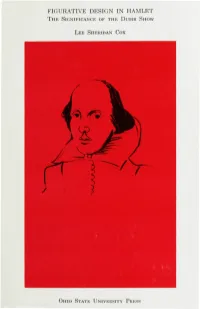

Figurative Design in Hamlet the Significance of the Dumb Show

FIGURATIVE DESIGN IN HAMLET THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE DUMB SHOW LEE SHERIDAN COX OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS $8.00 FIGURATIVE DESIGN IN HAMLET The Significance of the Dumb Show By Lee Sheridan Cox Critics have long debated the significance of the dumb show in Hamlet. There is a wide divergence of opinion on the matter of its importance: to one critic, it is ''only a mechanical necessity"; to another, "the keystone to the arch of the drama." In mod ern performances of Hamlet, it is frequently omitted, a decision vigorously protested by some critics as detrimental to the play scene. But the presence of the dumb show in the play scene has given rise to questions that evoke little unanimity of response even among its proponents. Why does the mime directly anticipate the subject matter of The Murder of Gonzago? Does Shakespeare preview Gonzago to provide necessary in formation? If not, is the dumb show then superfluous? And if superfluous, was the de vice forced on Shakespeare, or was it merely a politic catering to popular taste? Is the show foisted on Hamlet by the visiting players? If not, how does it serve his larger plan and purpose? What is its effect on the stage audience? Does Claudius see the pan tomimic prefiguring of Gonzago? What does his silence during and immediately alter the show signify? The search for answers to such questions is usually confined to the play scene. But Professor Cox maintains that the true na ture and function of the show can be ap FIGURATIVE DESIGN IN HAMLET THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE DUMB SHOW FIGURATIVE DESIGN IN HAMLET THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE DUMB SHOW LEE SHERIDAN COX OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS Copyright © 1973 by the Ohio State University Press All Rights Reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Cox, Lee Sheridan Figurative design in Hamlet Includes bibliographical references. -

1 | Hudson Valley Shakespeare Festival

1 | HUDSON VALLEY SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL TABLE OF CONTENTS OUR MISSION AND SUPPORTERS EDUCATION DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT PART ONE: SHAKESPEARE’S LIFE AND TIMES William Shakespeare Shakespeare’s England The Elizabethan and Jacobean Stage PART TWO: THE PLAY Plot Summary Who is Who: The Cast The Origins of the Play Themes A Genre Play: Revenge Tragedy or Tragedy? PART THREE: WORDS, WORDS, WORDS By the Numbers Shakespeare’s Language States, Syllables, Stress Feet + Metre = Scansion Metrical Stress vs. Natural Stress PART FOUR: HVSF PRODUCTION Note from the Director Doubling Hamlet: Full Text Vs. The HVSF Cut What to Watch For: Themes and Questions to Consider Theatre Etiquette PART FIVE: CLASSROOM ACTIVITIES Activities That Highlight Language Activities That Highlight Character Activities That Highlight Scene Work PART SIX: Hamlet RESOURCES 2 | HUDSON VALLEY SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL HUDSON VALLEY SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL OUR MISSION AND SUPPORTERS Founded in 1987, the Hudson Valley Shakespeare Festival's mission is to engage the widest possible audience in a fresh conversation about what is essential in Shakespeare’s plays. Both in production and in the classroom, our theater lives in the present moment, at the intersection of the virtuosity of the actor, the imagination of the audience, and the inspiration of the text. HVSF’s primary home is a spectacular open-air theater tent at Boscobel House and Gardens in Garrison, NY. Every summer, more than 35,000 patrons join us there for a twelve-week season of plays presented in repertory, with the natural beauty of the Hudson Highlands as our backdrop. HVSF has produced more than 50 classical works on our mainstage. -

Shakespeare, Madness, and Music

45 09_294_01_Front.qxd 6/18/09 10:03 AM Page i Shakespeare, Madness, and Music Scoring Insanity in Cinematic Adaptations Kendra Preston Leonard THE SCARECROW PRESS, INC. Lanham • Toronto • Plymouth, UK 2009 46 09_294_01_Front.qxd 6/18/09 10:03 AM Page ii Published by Scarecrow Press, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 http://www.scarecrowpress.com Estover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom Copyright © 2009 by Kendra Preston Leonard All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Leonard, Kendra Preston. Shakespeare, madness, and music : scoring insanity in cinematic adaptations, 2009. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8108-6946-2 (pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8108-6958-5 (ebook) 1. Shakespeare, William, 1564–1616—Film and video adaptations. 2. Mental illness in motion pictures. 3. Mental illness in literature. I. Title. ML80.S5.L43 2009 781.5'42—dc22 2009014208 ™ ϱ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Printed